Old Masters: Australia’s great bark artists

review by Peter Naumann

The National Museum of Australia’s latest exhibition is a revelation. From the bowels of their storerooms to the gleaming light of display have been brought 122 bark paintings created in Arnhem Land between 1948 and 1988.

The artists are some of the most influential of the past half-century. There are 40 bark painters in the exhibition, including Yirawala, Narritjin Maymuru, Jack Wunuwun, Mawalan Marika, David Maḻangi and George Milpurrurru, who have been fundamental to the resurgence and development of painting across Arnhem Land. Many of the works were originally part of the former National Ethnographic Collection, once housed in the Institute of Anatomy (the building that is now the National Film and Sound Archive).

They are outstanding works of art with dazzling visual impact. Within this group of works, painted in a limited palette of colours and using similar techniques, there is a remarkable variety of style and content. Many of the barks play with our sense of abstraction and reality, defying categorisation and logic. Sydney from the Air (1963) by Mawalan Marika shimmers with the vibrancy of the city and captures the roads and houses in a way that rivals the paintings of Dutch abstractionist Piet Mondrian.

collected by Karel Kupka at Yirrkala

National Museum of Australia

Next to it in the exhibition is Mithinarri Gurruwiwi’s Stone Axe Heads (1965), which though equally dazzling is on a completely different scale in terms of size and complexity of design elements. This bark depicts 16 rectangles, each half of which is yellow ochre while the other is either black or red. Arranged in four lines of four, they float like musical notes across a shimmering sheet of cross-hatched white lines. The simplest of compositions animates these stones and enables them to dance in tight formation.

collected by JA Davidson at Yirrkala

National Museum of Australia

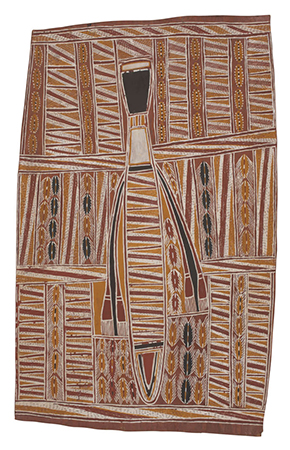

In other works, artists such as Dawidi depict the epic journeys of the ancestor beings as they created the laws and landscape. His painting of the Wagilak story captures aspects of ceremony, moiety laws, the natural forces of the monsoon and existential concepts of life, death and rebirth. Onto about a half-a-square metre of stringy-bark, Dawidi, using a myriad of pictorial elements, depicts the exploits of the Sisters Wagilak as they are enveloped by Wititj the Rainbow Serpent. In a related bark, Wagilak Ranga (1966), Dawidi paints the elder of the sisters. While this painting tells aspects of the same story it is almost devoid of pictorial elements. Dawidi instead employs geometry, patterns and symbolic elements to relate the epic journey.

collected by Helen Groger-Wurm at Milingimbi

National Museum of Australia

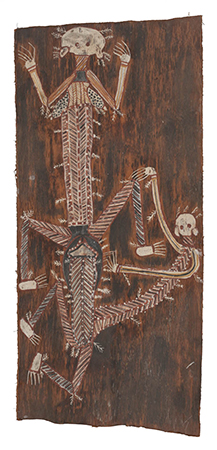

The exhibition divides the works according to geography, individual artists and stylistic groupings: ‘Portraits’, ‘Abstraction’, ‘Murals’, ‘Figures in the landscape’ and ‘Dynamic figures’. The latter includes a type of painting that was often commissioned to use sorcery to bring harm to a person who had wronged another, frequently through sexual infidelity.

collected in western Arnhem Land, Bennett Collection

National Museum of Australia

The overall exhibition display is thoughtful in its design, as is the information it provides. Each section has a short introductory text on the major themes. While the exhibition contains extensive explanatory material, this is kept separate from the art on display. A video plays behind a wall at the far end, while images of Arnhem Land landscapes dissolve into one another on a large screen at the conclusion of the show. A display case contains the actual palettes, earth pigments and brushes of two artists: Narritjin and Mawurndjul. The former is the focus artist of the East Arnhem section, while the latter became one of Australia’s most internationally celebrated artists.

Many of the walls and title graphics throughout the exhibition are coloured gold. Interestingly, gold also featured in another exhibition in Canberra, Gold and the Incas: Lost Worlds of Peru, which was held at the National Gallery of Australia over the summer of 2013–14. Gold has long held symbolic significance because it is long-lasting and precious. The frames of European paintings were painted gold, and the gold walls of the Old Masters exhibition are the design cue for us to associate the unframed barks with this ‘masterpieces’ tradition.

The commonality of gold in both exhibitions invites a few considerations about design styles of museums and galleries. In this case, they are somewhat contrary in style, content and display. The Museum has selected a display style of sparse clean walls, more often seen in art galleries, to elegantly display its bark collection, while the National Gallery has enlisted an ‘Indiana Jones’ style usually associated with museums’ display of precious objects from mysterious ‘lost worlds’. This is particularly apparent in the advertising material of the two exhibitions and even in the typeface of their titles and other wall text, with the Museum opting for a modernist sans serif font that associates the barks and their artists with contemporary art.

Although the alchemists behind the design at the Museum have followed the adage that if a little gold is good, then a lot must be better, the overall display at the Museum is elegant, thoughtful and enlightening. This is perhaps not too surprising, since the consultant curator for this exhibition was former senior curator at the National Gallery of Australia Wally Caruana. He, Howard Morphy and Luke Taylor and the team at the Museum have assembled a stunning exhibition. They have allowed the works of art space on the walls, cut windows through walls allowing views through to other sections and used changes in the colour and shape of the design elements to highlight individual outstanding works of art.

National Museum of Australia

However, like other Renaissance and Impressionist ‘masterpieces’ exhibitions that have toured Canberra previously, Old Masters lives up to its ‘masters’ title by being almost totally masculine, save for the work of Valerie Munininy 2. Perhaps, like Renaissance European art, this reflects the gender inequalities found in religious power structures and older customary practices. In Arnhem Land, men were usually associated with bark painting. Munininy’s 1980s work heralded the emergence of women bark painters.

The exhibition celebrates key artists by grouping their works under their names in a large, gold typeface, and by including photographic portraits and short biographical information about each artist. This is a far cry from the days, not so long ago, when a museum may have displayed the bark paintings of Aboriginal people with a label that acknowledged the collector, named the region from which the work was sourced and discussed the details of the story depicted, yet neglected to identify the person who painted it.

National Museum of Australia

The Museum does more than simply celebrate the individual creativity and genius of these artists. By careful selection and display, the exhibition presents a history of the development, or perhaps, more correctly, the ‘renaissance’ of bark painting and the cultural renewal of customary forms. The exhibition also presents a history of exchange and the release of knowledge about Aboriginal society, as each of these bark paintings represents a transfer of knowledge from Aboriginal cultures to a wider world audience.

A cabinet at the end of the exhibition displays the materials of bark painting, including a brush, called a marwat, which belonged to Narritjin Maymuru. The brush is a link that reminds visitors of the hands that so confidently laid out these complex works of art. Maymuru explained that each hair of the marwat is taken from a young clan member’s forehead and represents an individual idea, such that an artist can think ‘with’ or ‘through’ this brush. This concept of the brush as the medium through which the artist’s inner thoughts are expressed goes to the very essence of what art, and this exhibition, is – a revelation of ideas.

Peter Naumann is on leave from the National Gallery of Australia where he was formerly Head of Education and Public Programs.

| Exhibition: | Old Masters: Australia’s Great Bark Artists |

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia |

| Curatorial team: | Wally Caruana, David Kaus, Gretchen Stolte, Andy Greenslade, Samuel Fitzpatrick, Alisa Duff |

| Design: | Carola Salazar (Five Space Design) |

| Graphic design: | CampbellBarnett (Lea Barnett) |

| Venue/dates: |

National Museum of Australia, Canberra |

| Exhibition catalogue: | Old Masters: Australia’s Great Bark Artists, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2013, ISBN 9781921953163, A$39.95 |

| Exhibition website: | http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/old_masters |