Germans in Australia: 225 Years of German Immigration (1788–2013)

review by Eureka Henrich

Kangaroos, Aboriginal people, Uluru. When the Deutsches Auswandererhaus (German Emigration Center, or DAH) asked its visitors to complete the sentence ‘When I think of Australia, I think of …’, these three terms ranked by far the highest (the Sydney Opera House, koalas and the heat also rated a mention). These responses were the light-hearted introduction to the DAH’s temporary exhibition, Deutsche in Australien: 225 Jahre Deutsche Einwanderung (1788–2013) (Germans in Australia: 225 Years of German Immigration (1788–2013)).

The DAH is located in the maritime town of Bremerhaven, a short train journey from the city of Bremen. Still one of Germany’s busiest ports, between the 1840s and 1970s Bremerhaven was the launching pad for more than seven million emigrants. The DAH opened in 2005 to tell these people’s stories, injecting a more human element into a heritage landscape otherwise dominated by ships and seals (a maritime museum and ‘zoo by the sea’ are Bremerhaven’s other main attractions).

The success of the permanent galleries won the DAH recognition as the European Museum of the Year in 2007. These galleries reflect the dominant flow of Germany’s emigrants towards America, and include a memorable reconstruction of a waiting room on Ellis Island.

Audience interest in the 80,000 Germans who travelled ‘down under’ in the 1950s and 60s, as well as smaller numbers in the 19th century, has been growing ever since the museum opened, no doubt boosted by the new wave of young Germans who, since 2000, have taken advantage of the Australian Government’s working holiday scheme. In mounting the Germans in Australia exhibition, curators aimed to push beyond common associations to explore the long history of Germans travelling, working and living in the ‘fifth continent’.

As an exhibition about Germans in Australia for Germans in Germany, the approach created a satisfyingly holistic representation of the migration experience – encompassing multiple generations of migrants, their descendants, friends and family left behind, and those who decided to return home – as well as a less persuasive picture of contemporary Australia and the politics of migration, past and present.

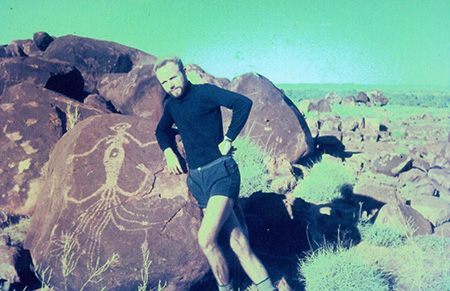

photograph by Kay Riechers

© German Emigration Center

The exhibition includes a small introductory area in which a stuffed red kangaroo, accompanied by two wallabies, takes pride of place. The distinctive sounds of Australia’s fauna (including the disconcerting grunt of a male koala) provide the soundtrack. A series of reproduced maps, from the late 15th century onwards, situated ‘Terra Australis Incognita’ in a European history of mythology, trade, exploration and ‘discovery’. At ankle height below the maps is a timeline of important markers in Australian immigration history, beginning in 1788 and including the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 and the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. This layering of contemporary and historical ideas, assumptions, images and policies work well to orient visitors.

The much longer timeline of Indigenous Australia is acknowledged (‘Asian Aboriginal Peoples’ are described as the ‘first arrivals’, coming here 40,000 years ago), and a bark shield souvenired by a German scientist in Queensland in the 1870s is displayed alongside the 1792 German translation of Captain Arthur Phillip’s journal. Elsewhere, Indigenous Australians featured as subjects of interest and concern for German missionaries and scientists, and the introductory exhibition text expresses regret over these individuals’ ‘racism and ignorance … in dealing with Australia’s original inhabitants in the 19th century’.

There has obviously been considerable thought given to the presentation of these difficult histories, but the apologetic tone works to curtail a more nuanced and historicised assessment of cross-cultural encounters. Nowhere in the exhibition are individual Indigenous Australians identified, making it near impossible to conceive of them as historical actors with their own responses and reactions to colonisation and the appearance and interference of numerous outsiders, including German explorers, missionaries and scientists. Without this, an exploration of the changing relationships between Indigenous Australians and Germans is also out of the question. Visitors are instead presented with ‘good Germans’ (the adventurous explorer Ludwig Leichhardt, represented in a 1938 portrait by his great-niece), ‘bad Germans’ (natural scientist, collector and suspected murderer Amalie Dietrich), and anonymous Aboriginal people.

photograph by Kay Riechers

© German Emigration Center

Beyond the introductory room, a huge, hollow rock-like structure filled with screens of different sizes dominates the main exhibition space. The images, which are screened as a slideshow, are simply titled ‘Australia 1970 – today’, and include the Sydney Harbour Bridge, crowds at Circular Quay, suburban streets and green hilly farmlands. Like the kangaroo, the Uluru structure reinforces the tourist image of Australia rather than interrogating it (and I began to wonder whether the Australian Embassy had a hand in the exhibition design!).

But the surrounding exhibits complicate the story, and introduce the ‘star’ pieces – not roos or rocks, but migrants’ letters, diaries and photographs, many from the collections of the DAH or lent by individuals for the exhibition. The opening chronological narrative is collapsed in most of these modules, with accounts and objects from different eras of migration combining to illustrate each theme. What emerges are continuities in the representation of Australia in Europe – emigrants’ guides from the 19th and 20th centuries repeat promises of a land of sunshine and good career prospects, and warn of the cultural oddities of the Australian people. For instance, a 1952 guide laments that ‘all the bars and movies are closed on Sunday. But foreigners will search in vain for what they are used to in Germany on weekdays too. There are no get-togethers with a glass of beer, no sundowners’.

A section on ‘the crossing’ includes an audio station where visitors can listen to readings of Phillip’s 1787–88 journal (Phillip here seemed to be an honorary German thanks to his father, a teacher who migrated to London from Frankfurt), and the diaries of German migrants from 1866 and 1954.

The narrative of travel times decreasing as technology improves is of course present, but is delightfully accompanied by the shifting significance of certain maritime rituals, such as the ‘on the line’ baptism. Initially practised by 15th-century seafarers to affirm their courage and faith before crossing the equator (perceived then as a life-threatening moment), by the 20th century a ‘baptism to the court of King Neptune’ had become entertainment. Migrants were rubbed with a smelly substance and then bathed, before being given a sea or weather-related nickname. A colourful certificate of Rainer Kroger’s baptism as ‘Bilgenkrebs’ (bilge crab!) on board the Vale in 1962 is signed by the captain of the ship. The survival of such documents speaks to the ongoing personal significance of migration journeys as memorable experiences marked by strangeness.

Australia’s attractions were, in most cases, the same for Germans as for other migrants – the promise of striking it rich on the goldfields of the 1850s, or taking advantage of assisted migration schemes to escape the devastation of Europe in the 1950s. German Australians’ experiences of internment and surveillance during the first and second world wars, however, set them apart as a group. An album displays the fascinating photographs of Paul Dubotzki who was interned in camps at Torrens Island, Holsworthy and Trial Bay Gaol (these recently rediscovered images were also part of the 2011 exhibition The Enemy at Home: German Internees in World War I Australia, held at the NSW Migration Heritage Centre in Sydney).

A map of Australia, curiously titled ‘German city names: from settler romance to political issue’, illustrates both the wide geographical spread of German settlers and the fluidity of certain place names. Each place name on the map is marked by the date it was named, as well as the date/s it changed. Some, like Ambleside in South Australia, reverted to their German name (Hahndorf) in the inter-war years, while others (like Birdwood, formerly Blumberg, also in South Australia) retained their anglicised form. The map also echoes a nearby section on the long-standing German Lutheran communities of the Barossa Valley.

Personal photographs are also used to furnish sections on the resettlement of German Jewish refugees and displaced persons following the Second World War. A selection of clippings from Australian newspapers, enlarged on the wall, demonstrates the ambiguity of the reception given to these post-war migrants – the embrace of skilled workers was tempered by fears about the possible migration of war criminals, which later proved well-founded (the text explained that 800 of the individuals welcomed to Australia as displaced persons were Nazi collaborators, of whom only three were put on trial).

© Collection German Emigration Center

Though the exhibition is text-heavy (with all panel text in German and English), this is broken up by a colourful collage of images, words and phrases used as a backdrop, and enlarged reproductions of documents and photographs. While this approach helps to overcome the problem of paper documents in glass cases (always too small and faraway to examine), it also highlights the overall scarcity of migrants’ objects on display. One of the few is a scruffy plush koala, which was given to Brigitte Beste in 1969 before she returned with her family to Germany after having lived in Australia for 15 years. The Beste family’s story is presented in a photo album, ‘There and back again’, part of a fascinating section on ‘re-migrants’, which explains that about 30 per cent of Germany’s post-war emigrants to Australia returned to their homeland by 1974. Return migration usually presents challenges for immigration museums, but for emigration museums this is their strength, as returned migrants bring with them their memories and keepsakes. The exhibition text notes that many return migrants ‘maintain a lifelong emotional connection with Australia’.

© Collection German Emigration Center

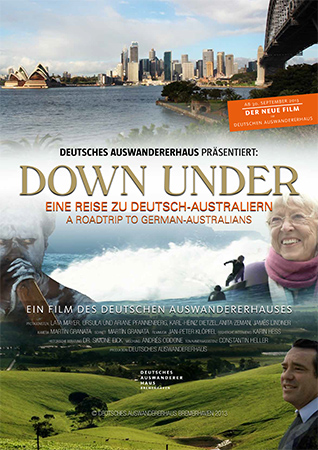

The ongoing emotional repercussions of migration are drawn out powerfully in DAH’s short documentary, which was made especially for the exhibition, and screened in the museum’s cinema. Down-Under: A Road Trip to German Australians follows three DAH staff as they drive between Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide interviewing those who stayed in Australia, rather than returning to Germany (along the way they visit 170-year-old shiraz vines in the Barossa Valley, planted by Prussians escaping religious persecution). One man tells them, ‘Deep in my heart, Australia is my home’. Some speak movingly of taking up Australian citizenship and casting off the shame of their family’s Nazi connections: ‘I became Australian and I discarded the guilt’. The film’s poster features the symbols that Germans most identify with Australia: the unique landscape, the Opera House and, of course, an Aboriginal person (in this case, a musician busking at Sydney’s Circular Quay).

Australians, too, have personal and collective memories of pasts rippled with guilt and shame. The dispossession, frontier violence and subsequent government policies of control that inflicted intergenerational harm on Australia’s Indigenous peoples have only recently begun to be officially acknowledged. The current psychological and physical harm endured by those detained for seeking asylum in Australia by boat may well be the subject of future government apologies. A recent history of grief and guilt, played out painfully across both personal and public stages, is common to both Germany and Australia. But my misgivings about the failure to engage with these connections in Germans in Australia are perhaps not pertinent to the exhibition’s aims.

The exhibition team have skilfully used the familiar to broach the unfamiliar and, in doing so, have revealed the important and ongoing engagement of Germans with Australia, as tourists, migrants, sojourners, settlers and, also, as Australians. Enthusiastic responses from visitors, and the extension of the temporary exhibition by a month, suggest that it is a success.

© Collection German Emigration Center

Eureka Henrich is a historian of migration to Australia and its representations, and is currently the Rydon Fellow at the Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, King’s College London.

| Exhibition: | Germans in Australia: 225 Years of German Immigration (1788–2013) |

| Institution: | Deutsches Auswandererhaus (German Emigration Center) |

| Curatorial team: | Dr Simone Blaschka-Eick, Tanja Fittkau, Lena Jung |

| Exhibition and graphic design: | Andreas Heller Architects & Designers, Hamburg: Alexander Kruse, Katharina Schätzle, Jutta Strauß, Alexandra Schäfer, Rebecca Kunz, Markus Sommer, Chad Danford |

| Venue/dates: |

Deutsches Auswandererhaus (German Emigration Center) |

| Exhibition catalogue: | Deutsche in Australien, 1788 – heute, published by Simone Blaschka-Eick, Bremerhaven, ISBN 9783000445743, €7.90 |

| Website: |

http://dah-bremerhaven.de |