Menzies by John Howard

review by Conan Elphicke

In January 1941, Prime Minister Robert Menzies set off by Qantas flying boat on a four-month trip to Singapore, the Middle East, Canada, the United States, Ireland and above all the United Kingdom. In England, Menzies hobnobbed with the great and the good, chief among them Winston Churchill, and sat in on War Cabinet discussions where he tried to, among other things, impress upon the British the need to bolster Singapore's defences.

Menzies' attempts to influence British strategy met with partial success at best, while his long absence further weakened his tenuous political support at home. As a significant feature of Menzies' troubled first term in office, the trip is also the most interesting aspect of Menzies by John Howard, a small exhibition by the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. The exhibition covers only Menzies' first term, from April 1939 when Joseph Lyons died in office, to August 1941 when Menzies was forced to resign due to lack of support within his own party.

Image: Paul Chapman, Developing Agents

At first glance, the limited scope seems unfortunate, in that it doesn't tackle the broad sweep of Menzies' long and defining second term and the huge impact it had on Australia. But in fact the choice is entirely suitable, especially given the museum's limited exhibition space. The exhibition provides a fascinating insight into this lesser-known but formative stage of Menzies' career at what was of course a significant point in Australian history. The exhibition explores how Menzies brought Australia onto a war footing and, crucially, worked with Churchill and Roosevelt while dealing with ructions within his own government.

The exhibition is housed in three small rooms and consists of a handful of well-chosen objects and a good deal of text written by guest curator, John Howard, who has just completed a biography of Menzies. The publicity surrounding the exhibition focuses on Howard's role, but in many ways this is its least interesting aspect. Howard is famously an ardent admirer of the man, so the perspective he provides offers few surprises – Menzies could do no wrong. However, the idea of a prominent guest curator is a strong one in that it raises the exhibition's profile and in this case allows the influence of Menzies on Howard to become a subject of the exhibition in itself, though not to the detriment of Menzies.

The most telling perspective is that provided by Menzies himself, most notably in the diaries he wrote while overseas. Two of these are on display, open at pages that include entries such as this, dated 22 March 1941:

Churchill['s] … real tyrant is the glittering phrase – so attractive to his mind that awkward facts may have to give way. But this is the defect of his quality. Reasoning to a predetermined conclusion is mere advocacy; but it becomes something much better when the conclusion is that you are going to win a war.

The second is dated 14 April 1941:

The Cabinet is deplorable – dumb men most of whom disagree with Winston but none of whom dare to say so. This state of affairs is most dangerous … Winston is a dictator; he cannot be overruled; and his colleagues fear him. The people have set him up as something little less than God, and his power is therefore terrific.

Today I decided to remain for a couple of weeks, for grave decisions will have to be taken about [the Middle East], chiefly Australian forces, and I am not content to have this solved by 'unilateral rhetoric'.

More excerpts from his diaries are available on the Museum's website.

Image: Australian War Memorial (AWM 007036)

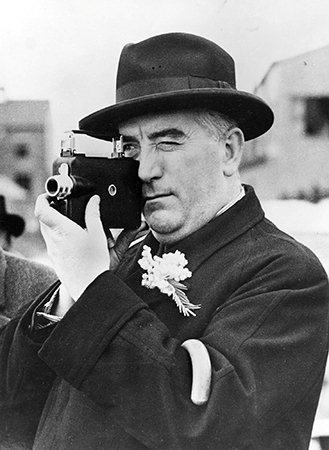

The small introductory room contains a single object – a 16mm Kodak cinecamera given to Menzies by a friend just prior to the trip. Menzies took the camera with him and well-edited excerpts of the colour footage he shot are on display in the exhibition's main room. These include scenes from the Middle East, blitzed London, English stately homes, and a sequence, presumably shot at Chequers, showing figures such as David Lloyd George, Eamon de Valera, Lord Beaverbrook, Clement Attlee, Anthony Eden and, of course, Churchill, looking oddly camera-shy.

We are used to these august figures only cropping up in stock footage, so seeing them in what is effectively a home movie is an eerie experience, especially because it was shot by someone you would not normally associate with such an activity.

Next to the film screen are two slightly strange objects. One is a silver casket containing an ornate scroll that gave Menzies the freedom of the Welsh city of Swansea, in grateful recognition of his services to the Empire. There is also a silver fruit platter from the good citizens of Sheffield. These are among several items on loan from the Menzies family that have not been on public display before.

Object: Museum of Australian Democracy Collection

Image: National Library of Australia (nla.int-nl41450-sc4)

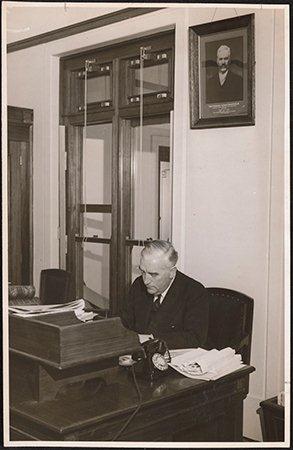

Other objects include the desk used by Menzies and many other prime ministers before and since, including Howard, who stumbled across it in 1999 and had it moved to his office. There is also an autograph book, a Longfellow poem signed by both Churchill and Roosevelt (whom Menzies also met on his 1941 trip), and interesting correspondence between Menzies and then Opposition leader John Curtin whom Menzies regarded as a good friend.

The exhibition suffers only from some navigation issues, in that it isn't immediately clear where it begins and ends. It peters out in the Senate Opposition Party Room where you can relax on an original 1927 easy chair and watch Menzies' home movies in all their unedited glory. Viewing these in a room similar to the one in which Menzies showed them to his colleagues has a transporting effect.

Image: Paul Chapman, Developing Agents

Menzies clearly learnt from the political mistakes he made before and during his first term. In December 1949, he began his second term as prime minister, reigning over Australia for an extraordinary 16 years. Hence current Prime Minister, Tony Abbott's, comment at the exhibition's launch: 'All of us, in our own way, are Menzies children'.

Menzies lives in the public consciousness as an imperious political colossus; as much an era as a man. But this exhibition lends him a human quality, and it is his words and camerawork that lie at the centre of this.

Conan Elphicke is a senior editor at the National Museum of Australia.

| Exhibition: | Menzies by John Howard |

| Institution: | Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House, Canberra |

| Curatorial team: | Guest curator: The Hon John Howard OM AC; Consultant historian: Ian Hancock |

| Design: | BannyanWood |

| Venue/dates: |

Museum of Australian Democracy |

| Exhibition website: | http://menziesbyhoward.moadoph.gov.au/ |