The mixing room: Stories from young refugees in New Zealand

review by Amy Hackett

Located on the fourth floor of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Passports aims to tell the stories of people who immigrated to New Zealand from the nineteenth century onwards. The exhibition opened with the museum in 1998 and, apart from the removal of an interactive computer game in 2006 following accusations that it peddled Labour government propaganda, Passports has remained substantially unchanged over the last 17 years.

For a regular visitor to Te Papa, the most interesting aspect of Passports is the Community Gallery that changes every 18 months to two years and allows different New Zealand communities to present their own stories of immigration. In the past, the community gallery has featured exhibitions from Chinese, Dutch, Indian, Italian and Scottish communities. At present, it is hosting The Mixing Room, an exhibition that tells the stories of young refugees – from countries such as Sudan, Bosnia and Iran – living in New Zealand today.

On the left, the young people from the youth forum welcome visitors and explain what a refugee is and how many come to New Zealand each year. On the right, a young man (Patrick John) also welcomes visitors and explains that the exhibition was made by refugee background youth.

photograph by Kate Whitley, Te Papa MA_I.302074

The Mixing Room differs from the other exhibitions in Te Papa in that there are no objects on display. Instead, the display in the narrow gallery is made up entirely of digital content. Three round tables with multi-user interactive screens encourage visitors to sit down and engage with the experiences of young refugees in New Zealand. The content displayed on these digital tables was created by 70 individuals out of their involvement in a series of workshops facilitated by Te Papa and held in Auckland, Hamilton, Palmerston North, Wellington, Nelson and Christchurch in 2009. The workshops included poetry and short-story-writing, drama, dance, documentary-making, and photography.

photograph by Kate Whitley, Te Papa MA_I.182887

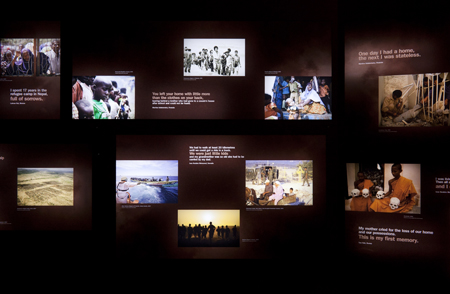

A changing series of photographs is projected onto a screen at the end of the gallery and the two long walls of the gallery are covered with backlit mosaics made up of photographs and quotations, all of which were contributed by the project participants. Beginning in 1870 and ending in 2008, a timeline runs along the floor from the main entrance to the back of the gallery and features the key global events – such as the Bosnian genocide and Sudanese civil war in the 1990s – that have led to people becoming refugees. Made of glass panels, the timeline is lit from beneath. Designed like stepping stones, the stages of the timeline encourage visitors to venture more deeply into the gallery and leads them towards the tables, and two standing computers at the end of the gallery. These computers invite visitors to view the blog associated with The Mixing Room.

photograph by Kate Whitley, Te Papa MA_I.302077

Besides the light given off by the screens, projected images and backlit walls and floor, the gallery space is dark, which increases the visibility of the image and textual content of the exhibition.

photograph by Kate Whitley, Te Papa MA_I.302078

The institutional voice of Te Papa is silent in The Mixing Room. Because there are no objects, there are no labels and minimal text. Besides a short explanation at the entrance to the gallery, the project is not elaborated. Visitors must refer to one of the interactive tables to obtain background information, and what is said about the project is written from the point of view of the individuals involved, including the brief quotations that feature on the walls. Given the small size of the gallery, the limited text is appropriate and does not overwhelm the visitor with information.

photograph by Kate Whitley, Te Papa MA_I.182893

One of the strengths of The Mixing Room is the way in which the limited gallery space has been utilised. By displaying only digital content, Te Papa has been able to fit a large exhibition into a small gallery, and the use of interactive tables means that Te Papa is not limited by the community gallery’s floor space. The uncluttered gallery is a fine example of how new technology and digital content can be employed to create an effective exhibition that is not limited by physical boundaries. Visitors can select from hundreds of options on the interactive tables and can tailor the information they see according to their interests. Visitors are encouraged to think for themselves and actively engage with the exhibition.

photograph by Kate Whitley, Te Papa MA_I.201818

The Mixing Room has occupied the community gallery since 2010. When I visited recently, one of the two standing computers was out of order and, apart from two posts from 2013, the exhibition blog had not been updated since 2012. While in one part of the blog the exhibition is described as ‘ongoing’, another part informs me that The Mixing Room was not intended to continue beyond 2013. Five years is certainly much longer than the usual 18 months’ to two years’ duration of other community gallery exhibitions. Is this because The Mixing Room has been such a successful exhibition that Te Papa has decided to extend the dates or is the community gallery low on the priority list? Possibly, there is simply no budget for refreshment and renewal. The gallery is an important space for giving communities a voice, and perhaps it is time for another community to have an opportunity to be represented at Te Papa. In the meantime, The Mixing Room remains relevant, especially in light of recent calls for New Zealand to increase its refugee quota.

Through its community gallery, Te Papa has acted as facilitator for this powerful exhibition, providing space for refugees to develop an exhibition from their own unique point of view. The process is more valuable than the end result; and on that basis, the exhibition must be rated a considerable success.

Amy Hackett is a student of museum and heritage studies at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and works at the Alexander Turnbull Library.

| Exhibition: | The Mixing Room: Stories from Young Refugees in New Zealand |

| Institution: | Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa |

| Curators: | Stephanie Gibson and Eileen Jacob |

| Exhibition design: | Ben Barraud |

| Graphic design: | Nick Clarkson |

| Venue/dates: |

Community Gallery, Te Papa, opened 10 April 2010 (ongoing) |

| Exhibition website: | www.tepapa.govt.nz/WhatsOn/exhibitions/Pages/TheMixingRoomstoriesfromyoungrefugeesinNewZealand.aspx |

| Gallery size: | approx 70 square metres |