Distant lines: Queensland voices of the First World War

review by Rebecca Lush

We are currently witnessing First World War centenary commemorations permeating many facets of our public history. Exhibitions, television shows, movies and books are being released en masse to explore the complexity and experiences of war. Perhaps inevitably, alternative stories of war are now emerging, as organisations grapple with the need to present new stories to interest and engage the wider public. In April 2015, the State Library of Queensland unveiled its centenary exhibition, Distant Lines: Queensland Voices of the First World War.

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Distant Lines actually comprises three quite distinct exhibitions spread across three levels of the library. These are titled, in order of ascending levels, ‘Conscription’, ‘War Front Experience’, and ‘Home Front Experience’. The largest and most significant of these, War Front Experience, is housed in the SLQ gallery and displays the stories of 25 Queensland soldiers at war, drawing on the library’s collection of war letters, diaries and images. It is this exhibition that lends itself to a critique here.

Through its title, Distant Lines: Queensland Voices of the First World War, and its accompanying promotional material, the exhibition establishes a number of preconceptions in the visitor’s mind about the sorts of stories and messages that it will contain. Most obviously, the visitor may expect individual stories of war by Queenslanders from their personal perspectives. ‘Distant lines’ also conjures romantic images of letters or postcards sent from faraway locations. The primary promotional image reinforces the play of words (battle lines and lines inscribed on paper): it is that of a lone soldier, his handwriting covering the bottom half of the poster. Again, this strongly implies the exhibition is focusing on personal stories.

War Front Experience is divided into two rooms: the entrance orientation room and the main exhibition space. The entrance supports the preconceptions mentioned above and successfully introduces visitors to the exhibition. In order to enter this space, visitors must move through a vestibule with two sets of automatic doors. The first door separates visitors from the open-air library. The second leads them into the entrance space. The doors effectively block outside noise and the sudden silence transports the visitor into a newly defined environment.

photograph by Leif Ekstrom, State Library of Queensland

Covering the four walls of this entrance space are the photographs and names of a random selection of Queensland soldiers who served during the First World War. In total, there are hundreds of these photographs, each approximately the size of an A5 piece of paper. The pictures have been sourced from official military records and are arranged by the men’s military units. These photographs completely envelop the visitor passing through into the main exhibition space. From personal observation, some visitors spent more time in this room than the exhibition itself, closely reading all the names, attempting to find a familial connection. The effect of walking through the double sets of doors into this enclosed and sombre space provides an emotional circuit-breaker that encourages a mood of quiet reflection for encountering the next part of the exhibition.

The main exhibition gallery is very busy, with large photographs showing scenes of war and some images of the 25 featured soldiers covering the walls. Mounted on these walls are framed black-and-white photographs of soldiers and their enlistment records or pages of letters. Scattered around the exhibition floor is domestic furniture from the war period and object display cases. In comparison to the entrance room, that is sparse apart from the pictures covering the walls, the main exhibition room appears unintentionally unorganised and frantic. The framed monochromatic photographs and documents blend into the multi-coloured wall space rendering them almost impossible to see when first observing the space.

Running directly down the centre of the gallery is a structure designed to resemble a trench. It is a large obstacle that is difficult to manoeuvre around, physically disrupting the overall flow of the main exhibition space. Within the trench is a small display tracing the story of schoolchildren embarking on a modern-day pilgrimage to Gallipoli. It seemed incongruous in this gallery and may have served a stronger purpose elsewhere.

There is no main narrative to the exhibition, but rather, it offers multiple stories that visitors can explore. This suits the exhibition content, as each individual soldier’s story is granted equal worth. The emphasis on individual stories is given further weight by the fact that there are no overarching thematic panels within the space.

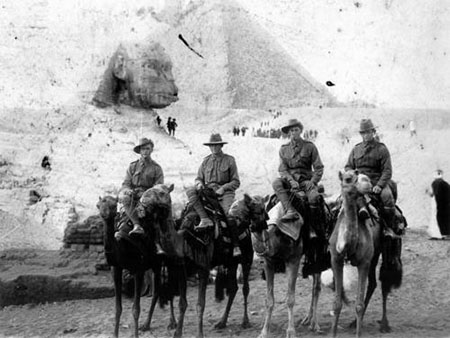

The exhibits relating to each of the 25 featured soldiers are scattered around the exhibition space. To access each story, the visitor must first locate a red board. As the boards are so brightly coloured, they are relatively simple to find among the clutter of the space. On each of these boards is a photograph of a soldier and their full biography. Located either beside or beneath the board is a display case, directly relating to the soldier, where visitors can view related objects. One example is Francis H Staunton, whose display case consists of postcards he sent from Egypt and an embroidered scarf purchased for his mother.

Each soldier’s objects raise different sets of themes that are explored in some depth on the object labels. Staunton’s scarf, for example, allows for a great insight into the varied reasons why soldiers went to war. Visitors become aware of the extent to which the First World War was seen as an adventure, an opportunity to explore the world. Souvenirs purchased and sent home embroidered with words of love and loss are reminders of this innocence. Many of these themes slot into larger experiences of war. The individual stories, however, are more intimate and personal.

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

The exhibition privileges the white male experience of war with little or no representation of other groups. This is a shame, as the sub-title of the exhibition, ‘Queensland voices’, suggests a range of perspectives. Although there was some information provided on Indigenous soldiers in the form of photographic material, their voices are not numbered among the 25 featured stories. Likewise, only one woman, Jane McLennan, is represented in the exhibition space.

Augmenting the physical display, films, audio clips and touchscreen devices engage visitors through a variety of receptors. For example, the first object a visitor encounters is the war diary of the 25 soldiers with an adjacent touch-screen. In this way, visitors are able to interact virtually with an object and delve further into its contents. While the layout of the gallery allows visitors to choose which soldiers to investigate and which to pass over, multimedia transforms a static exhibition into a multi-sensory experience to accommodate different learning styles.

photograph by Leif Ekstrom, State Library of Queensland

Although the exhibition is filled with voices, it is nevertheless a space of silence. It was a wise decision to ensure that all video and audio installations were either accompanied by headphones or set in a separate room from the main space. The silence allows for the written words to speak for themselves, while dimmed lighting adds to the solemnity of the mood. This is not problematic for viewing the objects as, although dim, the lighting is still adequate for reading the boards and viewing the objects.

The power of the stories displayed in the exhibition was such that I found myself engrossed for close to two hours. Although every soldier portrayed was from Queensland, the exhibition does not present a peculiarly ‘Queensland’ experience of war. Rather, the geographical coverage purely acts as a criterion for choosing the individual experiences being displayed. Reading each case study and viewing the related objects allows for a clear sense that there are dangers in standardising experiences of war. Each soldier reacted to and interacted with the war differently, based on their personal backgrounds, values and beliefs and, of course, the set of circumstances that they faced.

I found a photograph of my great-great-uncle on the wall in the entrance space among the hundreds of other faces. Before even entering the main exhibition space, it was a powerful message that the stories of the First World War are still inextricably linked to our present-day lives, and are an important part of what we have become.

Rebecca Lush is a Masters of Museum and Heritage Studies student at the University of Sydney, and a freelance historian, writer and editor with an interest in public history projects.

| Exhibition: | Distant lines: Queensland voices of the First World War |

| Institution: | State Library of Queensland |

| Curators: | Kevin Wilson and Robyn Hamilton |

| Exhibition design: | Daniel Sala |

| Graphic design: | David Ashe |

| Venue and exhibition dates: |

State Library of Queensland, Stanley Place, South Brisbane, 4 April – 15 November 2015 |

| Exhibition website: | qanzac100.slq.qld.gov.au/events/distant-lines |

| Gallery size: | 266 square metres and 117 square metres |