Road to recovery: Disabled soldiers of World War I

review by Rebecca Nuttall

Standing alone inside a particularly small exhibition space at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa), I noticed a visiting couple stopped in the doorway. ‘What’s in there?’ one asked. ‘World War I’, replied the other. They turned and left. It seems the ubiquity of war exhibitions is taking its toll.

The commemoration of 100 years since the First World War has begun energetically in New Zealand. In particular, 2015 has seen the opening of many new exhibitions commemorating the Anzacs and their struggles on the shores of Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. Sir Peter Jackson’s The Great War Exhibition in the Dominion Museum uses recreated street scenes and colourised war photographs to highlight the soldier’s journey. A light and sound show presented by the Wellington City Council utilised the public space of Pukeahu National War Memorial Park to host its commemoration. Te Papa’s long awaited Gallipoli exhibition opened to streams of visitors and the larger-than-life models and personal war stories alongside interactive displays and diary readings capture the horrors of the war on an intimate level that is not often seen in war exhibitions.

The modest and reflective exhibition reviewed here, however, opened long before this year’s war commemoration. Road to Recovery opened at Te Papa in August 2014, which was a less active period for centenary activities. The exhibition, held in the Ilott Room, sat on the periphery of the history and art exhibition space on Level 4 of Te Papa. Named after Sir John Ilott (1884–1973), an advertising executive and supporter of the arts who donated his collection to the nation, the space features regular exhibitions of works on paper from Te Papa’s collection.

photograph by Kate Whitley, ©Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

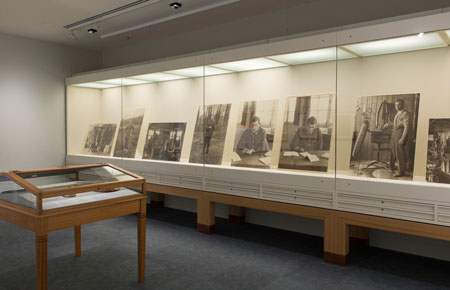

A simple rectangular space with white walls and a glass showcase, the Ilott Room has no surprises for those who enter (or do not enter, in the case of the museum visitors I encountered). Indeed, in contrast with the rest of Te Papa, the Ilott Room does not contain interactives, dynamic displays, audio recordings or children’s activities. It is a place to escape to, a space in which to contemplate – much like a traditional art gallery. Yet, this exhibition is not comprised of artworks but, rather – with a handful of photographs and objects – provides a glimpse into an aspect of war that is often overlooked or forgotten in our historical narratives.

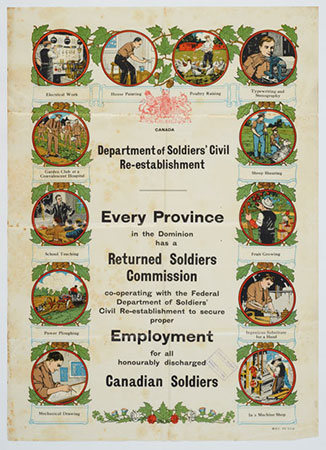

purchased 2013, Te Papa GH024220

Road to Recovery reflects on the physical destruction caused by the war. Exploring the ways in which disabled soldiers were supported at home and abroad, the two components of this sobering exhibition focus on how New Zealanders dealt with the impact that the First World War had on their personal lives and economic livelihoods. The first section features eight large original photographic prints of New Zealand men undertaking a training program established for disabled soldiers in 1917 at Oatlands Park in Surrey, England. They are displayed in a wall-length glass cabinet. Three framed posters on the opposite wall, two of which are replicas, give the exhibition context by indicating the way in which disabled returned soldiers were financially supported by official and charitable means.

photograph by Kate Whitley, ©Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The second component to this exhibition is a single wooden display case with a glass top that sits in the centre of the room. The case contains domestic pokerwork objects, such as a breadboard and trinket box, that were produced by returned soldiers whose chronic injuries made it difficult for them to hold down full-time jobs. A replica advertisement from the Evening Post for the Disabled Soldiers Shops sits beside the items. Such shops were set up in the 1930s to sell goods on behalf of the makers. On the other side of the cabinet, we are introduced to Fred Hansen (1880–1953), a tuberculosis patient and veteran from Oatlands Park whose embroidery was thought to be a favourite of Queen Mary. A visit from King George V and Queen Mary in 1917 provided the soldiers with an opportunity to exhibit their work.

photograph by Kate Whitley, ©Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The photographs in Road to Recovery are interesting also for their possible previous life as part of an exhibition held in London in 1918. Little is known about the origin of the photographs but curator Kirstie Ross believes that they were displayed in the Inter-Allied Exhibition on the After-Care of Disabled Men, which opened in Westminster Central Hall. This event was aimed to publicise national rehabilitation programs for soldiers and it included a variety of prostheses alongside photographs and films of soldiers undergoing treatment. The images were intended to be instructive, in the sense that they were used as tools of public persuasion rather than medical objectification. It is likely that these photographs were a way for the New Zealand Army to display their successful efforts at rehabilitating soldiers.

Now, almost 100 years on, these same eight photographs sit in a row within the wall-length glass cabinet They are at eye-level, slanting backwards slightly and spotlit. Images once used to highlight postwar achievements are now confronting and revealing. The aesthetic potential of the photographs is undermined by their poor quality: many of the faces are out of focus or fuzzy from movement. The cardboard mounts are deteriorating around the edges and one of the photographs has a large scratch down the middle. With no provenance, names of creators or way of identifying the subjects, these pictures retain the educational function of their original display in 1918.

Art and social history collide within the Ilott Room. The white walls and spotlights of a gallery space are contradicted by the wooden cabinet and poor quality photographs that suggest another kind of exhibition. Crafts, contextual posters and interpretation add the museum element that we expect at Te Papa, and thus bring the photographs to life. Utilising the different worlds of art and historical display, Road to Recovery asks us to question our response to these images.

Gift of Department of Defence, 1919 Te Papa GH016573

That Road to Recovery is not rich in resources and content makes it a reprieve from the current oversaturation of war memorabilia and battle stories. The silent space of the Ilott Room employs the rhetoric of the art gallery to encourage reflection, while a museum approach adds depth and humanity. Road to Recovery gives us the chance to contemplate the images of men who made it through the war but did not leave it behind. It asks us to consider how those men were perceived by society then and how we perceive them today. ‘First World War fatigue’ means that there is considerable value in an ostensibly uninviting room, and it is a shame the retreating couple did not come to the same conclusion on the day of their visit.

Rebecca Nuttall is a Masters student in the Museum and Heritage Studies program at Victoria University of Wellington.

| Exhibition: | Road to Recovery: Disabled Soldiers of World War I |

| Institution: | Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa |

| Curator: | Kirstie Ross |

| Graphic design: |

Nick Clarkson |

| Gallery size: | 36 square metres |

| Venue/dates: |

Ilott Room, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand, 16 August 2014 – 25 May 2015 |

| Exhibition website: | www.tepapa.govt.nz/WhatsOn/exhibitions/Pages/RoadtoRecoveryDisabledsoldiersofWorldWarI.aspx |