review by Mike Smith

This year a special conjunction of anniversaries has fuelled 'Darwin mania': 2009 is the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and 150 years since publication of his landmark study On the Origin of Species (1859). The frenzy of symposiums, new books, re-issues of old editions, exhibitions, television programs and postage stamps are testimony to the hold on the scientific and historical imagination that Darwin still has. For scientists, he is a heroic figurehead of science (though, as James Secord points out, his celebrity status only dates from about 1960[1]). For the general public, he is widely misunderstood as the father of the theory of evolution.

For museums this creates a range of challenges and opportunities. Darwinism is a global phenomenon. The intense scholarly interest in his life and ideas provides a splendid platform for international collaboration, especially if a museum can find a local angle. At the same time, the extensive coverage of Darwin in print and broadcast media allows plenty of room for cross-marketing — and Darwin largely brings his own audience.

The challenge is which story to tell. The Darwin story has many dimensions, all richly detailed. There is 'Darwin the boy' (with an interest in natural history) or 'Darwin the family man' (a respected member of the country establishment, balancing faith and radical scientific ideas). There is the development of evolutionary thought and the shifting social and intellectual impact of the new ideas. There is the web of correspondents, collectors, scientific and personal contacts that fuelled nineteenth-century science. There is the interplay of science, commerce, art and military interests in naval expeditions over the 60 years from Banks to Flinders to Phillip Parker King to Darwin. There is the wider story of British naval survey expeditions, or the particular story of the voyage of the Beagle, which opened Darwin's mind to the world. In many of these stories, Darwin is off-centre. For instance, he was only one of nine 'supernumeries' on the voyage of the Beagle. This in turn was only one of three naval survey voyages made by that ship, and Darwin had joined the voyage as gentleman's companion for Captain FitzRoy rather than as the official naturalist. So while Darwin's celebrity status is the hook for visitors, too linear a concern with Darwin as 'visionary' risks hagiography or (even worse) teleology.

Museums are best at stories that are intrinsically object-rich. Thematic exhibitions are more difficult to put together, because everything hinges on the interplay of interpretation, design and content. In these exhibitions, objects are props rather than drivers. And here is the rub. The key to understanding Darwin rests on how well his ideas can be communicated. Natural selection is a mathematical concept of breathtaking grandeur. Small, almost imperceptible, differences in the propagation of characteristics acting over immensely long periods of time produce an infinite array of life forms. It is a dizzying concept, one hard to capture in a museum exhibition, but crucial to explaining to visitors what all the fuss is about.

How well then does the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) do in its new exhibition, Charles Darwin — Voyages and Ideas that Shook the World?

The objects are somewhat predictable, comprising the usual detritus of nineteenth-century voyaging (maps, log books, watercolours, ships models, sketch books, survey and drawing instruments, and a modicum of natural history specimens and ethnographic objects). However, interest is maintained by well-placed installations: large images and audiovisual elements maintain the ambience and pace of a voyage; smaller audio posts allow visitors to hear Darwin in his own words; and there are fine recreations of Darwin's cabin aboard the Beagle and his glasshouse for orchids at Down House.

For visitors, the first challenge is finding this exhibition, which is tucked away below and behind the Museum's permanent exhibitions. An introductory module on the main floor serves as a portal to Voyages and Ideas. At this point a 'Who's who of survey vessels' lists the dramatis personae of the exhibition — the ships, ships' captains, artists and naturalists on each of the major voyages, showing a genealogy of British naval survey voyages. This very successful navigation device is continued throughout the exhibition — and reinforces the central idea that Darwin's voyage on the Beagle in 1831–36 was simply one of a series of these voyages.

Visitors then walk down a long ramp to the main exhibition on the floor below. Here the designers have made very effective use of the limitations of the building, dramatically creating the sense of an expansive journey with quotes from Darwin's Beagle journey.

In the main body of the exhibition, separate sections deal with the major voyages: HMS Beagle (1831–36); HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (1839–43); HMS Rattlesnake and HMS Bramble (1846–50). Each section includes biographical sketches of key individuals including the embedded artists (Augustus Earle and Conrad Martens) and naturalists (Charles Darwin, Joseph Hooker, Thomas Huxley) and the ships' captains. An audio installation (with headphones and audio loops selected by push-buttons) presents a pause point and one of the few exhibits aimed at the under-12s. Push the button for 'Pierre the crab' and you get a gallic-creole accent saying 'Hello, ma name is Pierre and I am a proud Mauritian crab with a small and perfect body'. This all very commendable, but it marks a point where the central narrative of the exhibition starts to fall apart.

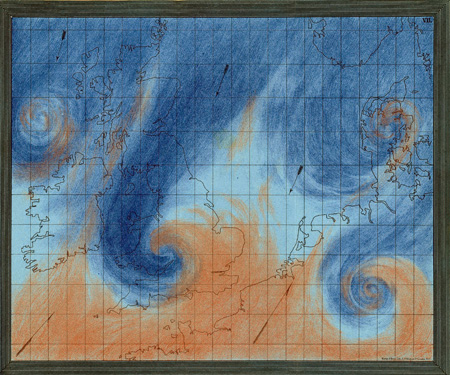

by Conrad Martens

by Conrad Martens

Voyages and Ideas gives a wonderful glimpse of the web of scientific connections that these British survey voyages involved. However, the impact of the Beagle on Darwin is under-developed, and is relegated to a panel of natural history specimens here and there, a few wall quotes and audiovisual posts. Much more could have been done to visually show the expansive biological diversity that the voyage impressed upon Darwin, and his attempts to make sense of this. The exhibition does little to explain what the key 'ideas' are or how they 'shook the world'. Nor does it return to the theme of a coordinated series of voyages and evaluate their impact and aftermath. We are told at the beginning that the impetus for these voyages was the prospect for trade with the new South American republics. Did this come about? The story of the voyages is left hanging, while the story (unsuccessfully) diverts to follow Darwin, the ostensible celebrity raison d'être for this exhibition.

We cannot expect museum exhibitions to do everything, but it is often said they need to become better at storytelling. For interpretative exhibitions, this requires a set design with some visual and emotional impact, and clear narrative structure. This attractive exhibition gets some of the way with the 'voyages' but would have benefitted from some help from theatre and installation artists in tackling the more complex task of presenting the 'ideas' and showing how they 'shook the world.

Mike Smith, an archaeologist and environmental historian, is a senior research fellow in the Centre for Historical Research, National Museum of Australia, and an adjunct professor in the Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra.

| Institution: | Australian National Maritime Museum |

| Curatorial team: | Nigel Erskine, Michelle Linder (curators), and team Lindsey Shaw (co-ordinator), Nigel Erskine, Michelle Linder, Johanna Nettleton, Daniel Weisz, Daniel Ormella, Will Mather, Caroline Whitley, Susan Bridie, Jeff Fletcher |

| Design: | Exhibition design, Johanna Nettleton, Daniel Weisz; Graphic design, Daniel Ormella |

| Exhibition space: | 530 square metres |

|

Venue/dates: | Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney, 30 March 2009 – 23 August 2009 |

| Publication: | In the Wake of the Beagle: Science in the Southern Oceans from the Age of Darwin, Iain McCalman and Nigel Erskine (eds), UNSW Press, 2009, RRP A$49.95. [Note: This book comprises papers from a two-day seminar presented by ANMM and University of Sydney 20–21 March 2009 to mark the opening of the exhibition Charles Darwin — Voyages and ideas that shook the world, richly illustrated with images from the exhibition]. |