review by Peter Stanley

Viewers of the BBC series The Museum will recognise Irving Finkel as the generously bearded assistant keeper at the British Museum, shown variously inspiring primary school children to piece together cuneiform fragments and helping the police with their enquiries about Babylonian antiquities looted from Iraq. Clearly destined for the small screen, Dr Finkel can now be found explaining the Babylonian world view on the British Museum's Babylon website.

Dr Finkel, with Michael Seymour and a group of academic and museum collaborators, has produced both an intriguing exhibition, Babylon: Myth and Reality, and a detailed catalogue of the show. The nature of the exhibition — exploring both the reality of ancient Babylon and the lingering connotations of the idea of it over the centuries — makes this review bi-focal, or even multi-focal. In it I will examine the exhibition and the accompanying catalogue and consider the effectiveness of their treatment of both the historical reality and the myth-in-history, and reflect on the relationship between exhibition and catalogue.

Babylon is a major venture, sponsored by the Blavatnik Family Foundation to a total cost of £502,000, an expenditure that has produced a hybrid. While it includes an exciting selection of artefacts and reconstructions introducing the visitor to ancient Babylon, it is not just an expert visit to a site and a culture. Nor is it only a tour of the various ways in which the idea of Babylon persisted long after the Mesopotamian desert reclaimed the city's site. The idea of connecting Nebuchadnezzar's city of 600-odd BC with the complex connotations of the name and even the Babylon of 2008 under the stress of foreign occupation, is a fruitful one. It seems obvious that the British Museum needed to find a 'hook'. We might imagine how scholars interested in ancient Babylon ran up against marketing staff who might vaguely remember the 1978 Boney M disco hit, 'Rivers of Babylon'. We can picture the planning meetings at which marketing staff must have wept with relief when they realised there was a way of 'selling' an otherwise esoteric exhibition about a place that few visitors can have the remotest knowledge.

But this hybrid conception sets up an immediate tension between the substantive content (actual artefacts of a real, if remote, place) and the framework of the 'myth' of Babylon (a rag-bag of cultural references culled from 2500-odd years of art, literature, classical and popular music). Do the two aspects of the concept gel? What sort of exhibition is this? How effective can it be?

Surprisingly, perhaps, the exhibition worked, though not flawlessly. It was located in a slice of the silo occupying the centre of the British Museum's Great Court. It was compact and arranged in a complex maze of about nine rooms or corridors. I visited on a busy Sunday afternoon soon after its opening in November 2008, and in the company of a companion in a wheelchair. The number of visitors aggravated the limitations of small rooms, narrow gangways and showcases placed at inconvenient heights. We shuffled along in the familiar blockbuster manner, tied to one side of the display, unable to zig-zag to see all of the ziggurats. My wheelchair-bound companion saw less than I could, and I missed some cases and panels simply because I could not make my way through the press of other visitors. Nevertheless, even the constricted views I had of many objects impressed me powerfully.

The exhibition was carefully structured, beginning with an introduction to Babylon's location in time and space, a portrayal of 'The real Babylon' (actually more 'the real royal Babylon' of Nebuchadnezzar), treatments of the Hanging Gardens and episodes first known to Europeans through Biblical texts, such as the destruction of the Tower of Babel or Daniel in the lions' den. The final third dealt with 'The legacy of Babylon', demonstrating how it generated pervasive ideas, such as the 60 minutes and seconds of our hour, and showing expressions in art of the idea of Babylon through time; indeed, up to Iraq today.

by Lucas van Valckenborch

oil on panel

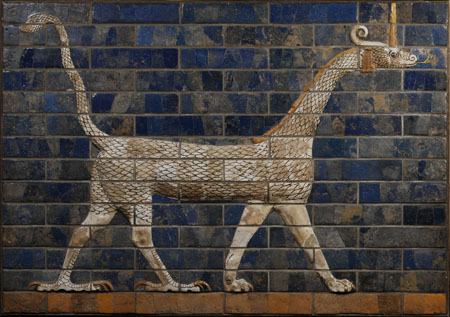

Ironically, for all of Saddam Hussein's crimes, it is because he ludicrously identified with Babylon's ancient rulers his notorious regime arguably took greater care of ancient Babylonian sites than did those who overthrew him. A disturbing series of slides at the end shows the damage inflicted upon ancient sites in the aftermath of the invasion and occupation of Iraq by United States forces and their allies (including Australia). Reprehensibly, American forces established a base immediately next to the site of the Processional Way, and heavy vehicles have caused irreparable damage to the remains of its mud-brick foundations. Individual soldiers hunting for souvenirs have prised out hundreds of bricks from the remains of the Ishtar Gate in a kind of slow-motion looting.

The exhibition's core is a display of about a hundred artefacts, a tiny fraction of the thousands of Babylonian objects collected by British, French and German antiquarians and archaeologists in the century or so after serious investigations began in the mid-nineteenth century. The British Museum's exhibition is one of three linked shows created by it, the Musée du Louvre and the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, which have cooperated to display the most compelling or attractive objects of their collections and those of a couple of dozen contributing collections. Many of the items on display are beautiful, even — in the true sense of the word — awesome.

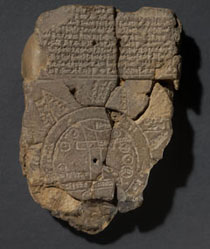

The stone or clay tablets covered with cuneiform — unintelligible to all but experts like Finkel — excited in me a curiosity about the Babylonians' language and knowledge; what their beliefs were and how their minds worked. So curious did I become about cuneiform and what it meant that I was impelled to find out how European scholars deciphered the wedge-shaped alphabet by reading Lesley Adkins's Empire of the Plains, a classic response for a museum-goer. If places like the British Museum exist to foster knowledge and appreciation of the human past among lay visitors then for me Babylon was a success.

The exhibition juxtaposes both the evidence of the 'real' Babylon with the representations of it and what they meant — the fabulous Hanging Gardens celebrated by the Greeks as one of the wonders of the world or the 'Whore of Babylon', symbolic of its supposedly essential depravity. These depictions, invariably executed without any knowledge of the place (even the site of which was lost until the mid-nineteenth century), demonstrate the tenacious power of a place for so long known only through biblical and classical texts. The representations encompass modern works as diverse as DW Griffith's spectacular film Intolerance of 1916, William Walton's vigorous 1931 oratorio Belshazzar's Feast, Jorge Luis Borges' short story of 1941, The Library of Babel, and even Kenneth Anger's 1959 exposé, Hollywood Babylon, expressing perfectly the association of Babylon with depravity. In popular music Bob Marley's frequent references to Babylon in Rastafarian music suggest the longevity and power of the name. A Google search on Babylon discloses thousands of references to apocalyptic biblical prophecy, suggesting what the name still connotes to countless people with little interest in the reality of Babylonian archaeology.

Whether an exhibition is the best way to convey this complex interpretation is a point to be pondered and debated by museum professionals and those interested in the role of museums in popular education. Even while marvelling at the artefacts, congestion during my visit impeded my grasp of the exhibition's themes. On a quiet day I would have had a better chance, of course, but lacking the time or stamina for prolonged study (not to mention more than the most superficial preliminary knowledge), a visit to the exhibition itself may not have been as productive as museum professionals probably assume or hope. The power of seeing the actual archaeological remains nevertheless goes a long way and no one who has seen the imposing lion brick-reliefs or the delicate tracery of cuneiform tablets would willingly look upon them only in the catalogue.

Still, it is surely through the beautifully produced catalogue that interested visitors will gain most in understanding, and the catalogue deserves as much attention as the exhibition. Reflecting the themes of the exhibition but not its exact form, the catalogue represents a scholarly achievement by its six contributors. Comprising some 32 essays on the city of Babylon, its history, legends and legacy, it offers readers the results of years of expertise in the subject. It is less accessible than the exhibition's relatively clear structure in that the essays range about a series of subjects of particular interest to the contributing scholars, rather than developing the exhibition's themes. I would argue that the catalogue's 236 pages give visitors far more detail than most want, and the scholarly tone must surely deter more than it gratifies. (Unforgivably, the catalogue describes the 'East India House Inscription' as 'a masterpiece of archaizing Babylonian epigraphy' — whatever that means.)

The catalogue's editors exemplify the axiom that most readers want to read less than authors want to write. Most contributors seem to have been much more comfortable dealing with the detail of, say, 'The truth about Etemenanki, the ziggurat of Babylon' than with exploring the cultural and artistic expressions of Babylon's image through succeeding centuries. While the marketers evidently scored a win by inducing the experts to embrace the legacies of Babylon in the exhibition, it is apparent that the embrace was fleeting. In the catalogue, the experts attained their desire to tell us more than we really want or need to know about the subject that fascinates them.

Babylon: Myth and Reality is therefore a curious compound. It presented artefacts of great appeal regardless of visitors' knowledge alongside objects that require careful explanation in order to convey meaning. The exhibition itself presented learning accessibly. Even so, at least partly thanks to the prodding of the marketers, conscious of the need to attract lay visitors, it presented esoteric learning beside stimulating (and, in the case of the depredations of the Iraq occupation, sickening) contemporary references. The result is an exhibition that intrigues and teases, challenging visitors to comprehend a time and place of which they know little, and offering a comprehensible entry to that vanished world.

A catalogue gives the visitor an opportunity to nourish the curiosity aroused by a short and invariably unsatisfactory visit. At leisure, the visitor can comprehend what baffled or eluded on the spot, can extend knowledge (often impossible to imbibe while jostled or footsore) of what these items are, what they meant and how they came to be available to us centuries later. Invaluably, copious full colour illustrations of almost every item in the exhibition (and many more besides) enable visitors to pore over the detail in ways they cannot possibly in the exhibition. While too often written over the heads of lay visitors, the Babylon catalogue fulfils these expectations entirely.

Despite the respective flaws of exhibition and catalogue, each works with the other, giving visitors and readers a memorable and even startling insight into the reality of a particular ancient culture and its tenacious and creative half-life, and offering them a deeper understanding in print than a visit could practically give. Whether museum staff should be thinking more of the scholarly field in which they are expert than the audience to whom they seek to convey their passion is a discussion that ought to continue around every meeting table and in every staff common room in every museum.

Peter Stanley is the director of the Centre for Historical Research at the National Museum of Australia.

| Institution: | British Museum, London |

| Curatorial team: | Irving Finkel, Michael Seymour, John Curtis, Andrew George, J. Marzahn, Julian Reade and Jonathan Taylor |

| Design: | British Museum |

| Venue/dates: | British Museum, 13 November 2008 – 15 March 2009 |

| Publication: | Babylon: Myth and Reality, ed. Irving Finkel and Michael Seymour, The British Museum Press, London, 2008. RRP £25 |