review by Linda Young

National Museum of Australia

Australian Journeys replaces Horizons: The Peopling of Australia, the least effective of the National Museum's original galleries. This is not to say it was conceptually weak. On the contrary, the gallery brought forward some of the more challenging ideas among the Museum's first offerings to perceptions of Australian history, especially the idea that immigrants can be suspect as well as welcome. But the Horizons gallery lost momentum due to staff changes during implementation, and hence lost coherence. The gallery was further handicapped by unfortunate layout determined by the Museum's characterful architectural design. Not to put too fine a point on it, Horizons felt like a dark, twisting gulley — a daunting space.

So it is a relief to find that Australian Journeys is much more spacious. In fact, to keep up the littoral metaphor, the floor plan is like an open beach, studded with large and small vitrines among which the visitor wanders, spotting interesting things. This experience has its charms but, like a beach walk, there is not much to be drawn out of it beyond observing the variety of journeys undertaken by travellers to Australia and Australians to the rest of the world. Whether this is effective or sufficient is a big question, not only about the exhibition itself, but about the overall effect of the first generation of revisions to the National Museum's galleries.

National Museum of Australia

But first, let us consider the structure and dynamics of the new gallery. The technique of each exhibition element is to present an individual's journeying story, illustrated by one or more objects, with the personal story frequently carried into a bigger context with further objects. They are extended by a refreshing variety of labels, ranging from basic identifications to beautifully illustrated flip-books to touchscreens offering sequences of information at several levels.

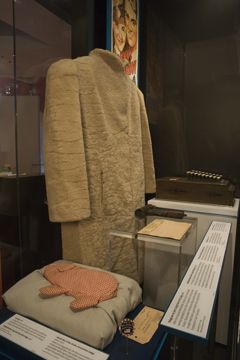

Thus the journey of Australian war brides to the United States in 1946 is recounted through the inspiration of a stuffed cloth toy pig, awarded to one-year-old Erin Craig as the child with the reddest hair on board a bride-ship. Photos of her young mother, her United States Army father and family gatherings over the next 50 years illustrate the Australia–America connection established by the Second World War. It's a vivid little view of the personal dimension of the big stories of post-war reconstruction and Australian–American relations.

Some stories focus on communities rather than individuals, as with the banner and organ of the Welsh Church in La Trobe Street, Melbourne, and a ceremonial eisteddfod chair. The persistence of emigrant culture in language, music and performance is an important theme in immigrant history, and the Welsh examples remind us that non-English speaking migrants came from not-very-foreign roots as much as they did from the more exotic. Welsh choral music plays through an audio chair (practically the only seating in the whole gallery), and I found myself singing along to 'Land of my fathers' in the degenerate version I learned from my London–Welsh grandmother, beginning 'My hen laid a haddock on top of a tree ...'

National Museum of Australia

These cases exemplify the obvious focus on the journeys of immigrants to and emigrants from Australia, but the very short introductory statement to Australian Journeys positions the gallery as evidence also of traders and travellers who connected Australia to the rest of the world. The permutations of this proposition are explored with some ingenuity.

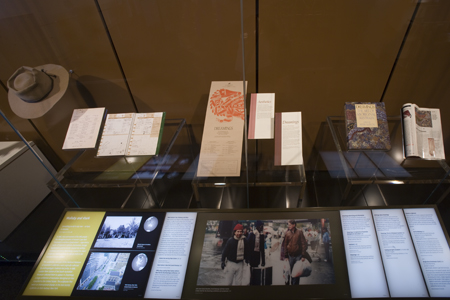

Thus, for instance, there is an exquisitely reflexive story about Australian Indigenous culture travelling abroad via exhibition, in this case, the 1989 Dreamings. Prepared by the South Australian Museum, it was the first big show in America of Central Desert dot art, contextualised in other traditions, including several Wik sculptures from the National Museum's collection. Hence Wallaby and Shark join curator Peter Sutton's hat, his 1989 New York diary, and the exhibition catalogue in the vitrine about the exhibition. The museum itself is presented as an agent of Australian cultural transmigration.

National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

On another track, a case of Staffordshire pottery figurines focuses on two models of the Irish nationalist, William Smith O'Brien, transported to Port Arthur in 1848 and pardoned in 1856. A handful of other Staffordshire figurines have a connection to Australia: Sir John and Lady Franklin (who both rose to celebrity when Sir John disappeared into the Arctic in 1845), the Wagga con-man known as the Tichborne claimant and bushranger Frank Gardiner. Such celebrities immortalised in china show that the British potteries maintained an eye on the colonial market and responded to its interests — evidence of the two-way flow of taste and consumption within the Empire.

The four examples cited so far are genuinely pretty random, but all of them represent what I feel are shallow limits to the Australian history depicted in the Australian Journeys gallery. The notion of human 'stories' as the way to enliven impersonal history has become the conventional wisdom of museums in the early twenty-first century. But somehow, 'stories' have become separated from purpose or narrative connection. In Australian Journeys, we see the low tide of narrative history and its consequence, a flotsam of stranded stories.

The ironies of this view are considerable, for the National Museum of Australia has been analysed and criticised for the quality and content of its presentations as no museum in Australia has ever been. Even before it opened, the Museum approach was described as motivated by 'fear of the master narrative', anticipating, as it later said in its own submission to the 2003 review, that narrative could privilege some views while suppressing others. The absence of narrative was among the major critiques of the Carroll report and, while I disagreed with the report's premises and most of its conclusions, my own submission included the same call for narrative themes. Yet the Museum's new gallery has again fled the spectre of a continuous thread of historiographic purpose — if that is what is meant by 'narrative'.

Of course, there are narratives and narratives: singular grand epics in the ancient tradition of the Odyssey or the Kalevala, and interwoven stories in the modern style of multiple perspectives. Carroll himself advocates that nations need narratives of archetypal myths to unify the people, and that Western societies are presently 'dying for want of a story'.[1] This is not the kind of story I have in mind when I lament the absence of narrative in Australian Journeys. Rather, it is the idea that overarching ideas convey meanings beyond the elements on display; that a bigger account can be told, perhaps along the lines of global movements of people making new lives, willingly or unwillingly. I regret that Australian Journeys pursues no arguments that might be demonstrated or challenged by personal object stories — themes such as the transmission of cultures, the effects of a transplanted law, the hybridisation of traditions over space and time.

It seems to me that the crux of the reluctance to risk big pictures is the unspoken pressure on museums to address all interests in Australian history. The absurdist extreme in this scenario was instituted in the first incarnation of the Museum of Sydney, with the 'Bond Store' audiovisual, in which faces loomed out of the darkness to sing or rant at the bewildered visitor, in the name of the visitor 'making up his/her own history', with no reliable historic thread available anywhere. Adelaide's Migration Museum, by contrast, experimented in various ways, such as presenting two different (in one case, gendered) tracks through an exhibition on sport, to demonstrate that sexist structure over-determines individual agency in that aspect of history. Visitors came to personal conclusions because they traced different experiences in the exhibition.

From the beginning, the National Museum of Australia took a smorgasbord approach, with a bit of this, a bit of that and a bit more of something else, the bits usually grounded in ethnicity to present a multicultural veneer over everything. Horizons followed this route, focusing on post-Second World War migration and featuring at its opening a segment on the very latest war-ravaged immigrants, the Kosovars. Australian Journeys follows an even looser model, a beautifully contrived beach decked with stories.

For a museum that has been so savagely treated by powerful interest groups, perhaps this is a rational approach. No one could have predicted that the government would have changed by the time the first revisions were realised, and that the history wars would have become practically irrelevant since the official apology to the Indigenous people of Australia in 2008. Unfortunately, there is evidence that the Labor government is keener on symbolic gestures than putting real resources into museums and heritage. But the arm's length distance between government and its agencies permits a more honest circumstance in which to present history to the public than the Howard-style of Realpolitik, in which he who pays the piper calls the tune.

Linda Young is the course director, Museum Studies and Cultural Heritage, Deakin University, Melbourne.

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia |

| Curatorial team: | Gallery brief prepared by Mat Trinca and Kirsten Wehner. Curatorial team: Kirsten Wehner, Martha Sear, Cheryl Crilly, Laina Hall, Susannah Helman, Michelle Hetherington, Lynne McCarthy, Alison Mercieca, Rebecca Nason, Megan Parnell, Rathicca Chandra, Karen Schamberger, and Jennifer Wilson |

| Design: | Cunningham Martyn Design (exhibition design); Beattie Vass and National Museum of Australia Print Publishing (graphic design); Thylacine Design and Project Management (object supports and sensory station design) |

| Exhibition space: | approx. 650 square metres |

| Australian Journeys was developed by a large multidisciplinary team that included National Museum of Australia staff and external contractors. |