review by Nicole Ma

The National Museum of Australia's website describes Circa as an audiovisual revolving theatre 'taking visitors on a unique visual journey through history'. It is a stand-alone theatre that leads into the exhibition areas. Visitors enter the seating area during an audio introduction. The seating area moves through subsequent quadrants that feature short segments (3–5 minutes) in a multi-screen theatrical setting. A revised version of Circa was completed in 2009, in response to a review of the Museum's exhibitions and programs chaired by John Carroll.

Based in Boston in the United States, Anway & Company won the worldwide tender to design the inaugural exhibitions for the National Museum of Australia, which opened in 2001. Anway, in partnership with American company Batwin and Robin, created the concept and design for the original Circa, which was then produced by Night Corporation. Circa's inaugural brief was to introduce visitors to the Museum and to the country of Australia. Dawn Casey, the Museum director at that time, instructed the producers to encourage visitors to go out and buy a ticket to the rest of the country. Each quadrant (in the original version, there was no film element in the first quadrant) concentrated on one of the themes explored in the Museum: land, nation, and people — in other words, the history, culture and identity of Australia.

National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

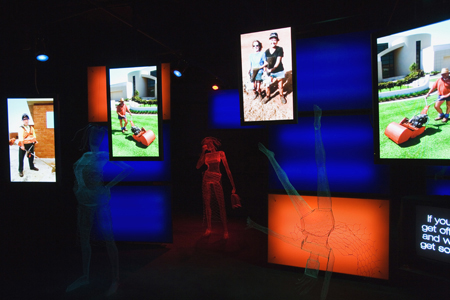

Circa, as originally conceived, was intended to be a theatrical experience, arousing in visitors surprise, engagement, curiosity and anticipation. The program demanded a high level of creative and technical expertise. High production values (cinematography, direction and editing), dramatic lighting and immersive surround sound were critical to achieving an engaging and memorable beginning to the museum experience.

The original Circa used 35-millimetre photography, colour manipulation and juxtaposition of images (the red desert next to a bright green lawn watered by sprinklers) to create a statement and achieve a visual composition that was fresh and unique. The images were augmented by a soundscape that meshed familiar musical themes, Indigenous music, cut-up popular music and real-world sound effects. The overall effect was impressionistic and subjective. The graphic visual interpretation of land, nation, and people aimed to intrigue. It could be considered an audiovisual meditation, or poem, on what and who is Australia.

The current Circa focuses more strongly on an introduction to the Museum. Images and narration are used to construct a compact overview of Australian history. Music drives the story forward and builds to moments of historical significance. The voices/narration are objective and strive for balance and impartiality. It educates and entices the visitor to learn more. The Museum's website says, 'History is, among other things, a story' and 'the story presented by Circa is one that has great relevance to the history classroom'. As such this version of Circa fulfils its declared aim 'to communicate that the Museum interprets history through material culture'.

One of the definitions of a museum is a building or institution where objects of artistic, historical, or scientific importance and value are kept, studied and put on display. How can an exhibit like Circa, charged with the goal of enticing and engaging visitors, fit that criterion?

The original Circa's approach presented an egalitarian liberal view. It appealed to the emotions and some of the messages were even interpreted as subversive. Visitors were invited to become immersed in the images and think about what they were seeing and come to their own conclusions. It placed Australia in the global village and commented on issues that affected us, such as climate change, large-scale immigration, tensions between the city and the bush. It asked questions without attempting to answer them. It did not address the notion of interpretation of history through material culture.

The current Circa has a more traditional flavour. Information is carefully constructed to present a balanced and fair interpretation of Australia's social history. It expresses traditional attitudes and values without speculating on the benefits or otherwise of change or innovation. It concentrates on the stories of Australian history using the program as a tool to educate. It does not refer to how Australia relates to the rest of the world or where the country is headed. It does, however, address the notion of interpretation of history through material culture, and more particularly through its own collections.

These two programs are vastly different. One is subjective, innovative, emotional, while the other is objective, traditional, and conservative. Is one better than the other? Or can they be seen as a reflection of the times, a capsule of history and indicative of the 'zeitgeist' or spirit of their respective period or age. Do they represent the inevitable nature of change, when a pendulum after swinging to one side must then swing to the other? The analogy that comes to mind in this instance is that of a poem versus a lecture. Some people like to read poems while others prefer to listen to a lecture.

Nicole Ma is an award-winning filmmaker based in Melbourne. She was executive director of Circa (2001).

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia |

| Curatorial team: | Kirsten Wehner, Jennifer Wilson and Bronwyn Dowdall |

| Production and Design: | Bearcage Productions (production); Christina Smith (design); Nick Schlieper (lighting design); Michael Yezerski (composer) |