Mapping our world: Terra incognita to Australia

review by Campbell Macknight

The title of this wonderful exhibition contains a subtle ambiguity. On one reading, it suggests that the exhibition is concerned to show the evolution of our understanding of the globe from earliest times to a period when the outlines of the continents had been fixed with some reliability. In terms of Western knowledge, this runs from Babylonian clay tablets to the early 19th century, when chronometers were sufficiently accurate to allow determination of longitude. 'Our world' in this reading is the globe itself and 'mapping' principally involves fixing the shape of the land and ocean.

On another reading, 'our world' refers to the Australian continent, where the well-known sequence of European ideas and coastal discoveries is supplemented by some Aboriginal maps of particular stretches of country. Apart from these Aboriginal items, the latest map is the 1822 Admiralty revision of Flinders' chart of the continent, showing the latest discoveries of Phillip Parker King, which effectively completed the familiar outline of the continent's coastline.

Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice

The move from one interpretation to the other, as suggested in the exhibition's subtitle, is the storyline of the exhibition. While one might quibble about the lack of any treatment of the concept of geographical space in other cultural traditions, the trail from Mesopotamia, through the Classical World, to the Arabs and the Middle Ages, on to early modern Europe and thence to Australia is sufficiently clear to make a coherent story. And how wonderfully the story is told, with maps from major European collections as well as Australian sources, public and private, and the library's own strong holdings! This is a generous selection of the highest quality maps of their day, each of scholarly importance for one reason or another. The spectacular star of the show is the Fra Mauro map of 1448–53 from Venice, but there are many other large and beautiful contenders. The maps are supplemented by a small, but well chosen, selection of objects. It matters not one bit that the Harrison chronometers (H1 and H4) are modern replicas, given their importance in the story of longitude, while the two Earnshaw instruments, so familiar to readers of Flinders' Voyage to Terra Australis, are the real thing.

Norman Banham Collection, Canberra

photograph courtesy National Library of Australia, Canberra

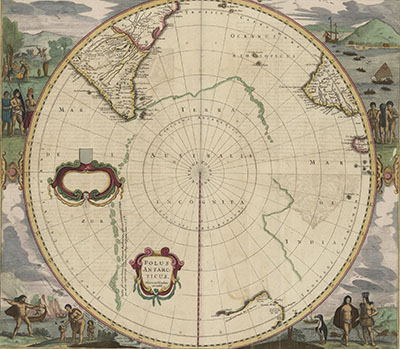

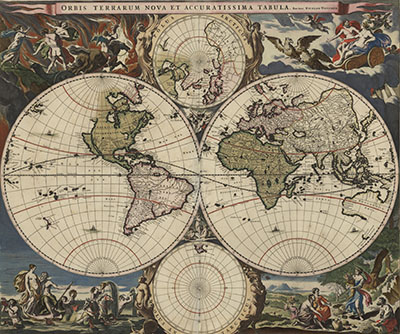

Considering the exhibition as a whole, rather than as a collection of wonders, its most striking quality is its 'density'. By this I mean the possibilities it offers for comparison between items and the deeper investigation of a particular item. In part this arises from the display of complete maps. Take, almost at random, the Hondius map of the Antarctic pole of 1641 and the Visscher world map of 1658, with its insets of the polar regions. Both are held by the library itself, the first as part of the Tooley collection bought in 1973, the other a recent purchase. Tasman's voyage of 1642–43 provided much more detail on Australia for the later map and also served to blow away some of the more fanciful and vague southern coasts on the earlier one. As well, there are significant differences between the representations of South America and of South Africa, to say nothing of the stylistic transformation of the surrounding images. How did Hondius manage to combine a penguin with two almost naked figures? One's imagination and questions are controlled, though not exhausted, by Martin Woods's excellent catalogue essay on the two maps.

National Library of Australia, Canberra, Tooley Collection, Map T 727

The catalogue itself is another reason for the 'density' of the exhibition. It is, in itself, a major scholarly resource – and far too heavy to carry around the exhibition. The 20 'contributing authors' who comment on individual items have been given enough space to explain and discuss, in addition to providing basic information. Particular praise is due for the quality of reproduction of the images, both in trueness of colour and sharpness of line; I have had the magnifying glass out reading tiny place names and captions as I study the pages at leisure. Even finer detail is available for many items in web images accessed through the exhibition website on www.nla.gov.au. It would be helpful to keep this material available for some time after the exhibition itself closes. There is a great deal to revisit here, in person, in print and online.

National Library of Australia, Canberra, Map RM 4641

The venue deserves mention. Most major libraries these days have an area in which to display 'treasures' and the provision of adequate space for this has been one of the driving causes of the recent refurbishment of the National Library's ground floor. There have been successes here in the past; one thinks of the original Treasures from the World's Great Libraries exhibition in 2001 or the more recent Handwritten: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Treasures in 2011. Given the institution's long interest in collecting maps and their potential for impressive display, an exhibition on the theme of maps is hardly surprising. This exhibition marks a step forward, however, in that, like a good museum display, it tells a story, rather than being just a collection of interesting or beautiful objects and documents. It illustrates perfectly the point that great collections are not much use without expert and imaginative curators who, from their knowledge not just of their own collection, but also from their global scholarship, can command the intellectual resources required for an outcome of this quality. The team of Martin Woods, Nat Williams and Susannah Helman delivers the goods, and the sponsors of this exhibition can be well satisfied with the fruit of their generosity.

photograph by Craig Mackenzie, National Library of Australia, Canberra

In one sense, of course, the major sponsor is the public. I must confess to a little worry when I first heard about the proposal for such an exhibition. Would the people come? I am delighted to have been proved comprehensively wrong. Russell Crowe – an inspired choice to open the exhibition – supplied a good dose of initial publicity and this was followed by extensive advertising, to excellent effect it seems. The strategy of compulsory booking, even with free entry, has worked well to maintain the flow of visitors at a comfortable level.

With Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, the National Library has shown how an exhibition can advance scholarship at the highest level, while, at the same time, it can attract, delight and instruct the public. The enterprise – as exhibition, catalogue and website – is a triumph.

Campbell Macknight has had a long interest in the maritime discovery of Australia.

| Exhibition: | Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia |

| Institution: | National Library of Australia |

| Curators: | Martin Woods, Nat Williams and Susannah Helman |

| Design: | Isobel Trundle |

| Venue/dates: | National Library of Australia, Canberra, 7 November 2013 – 10 March 2014 |

| Exhibition catalogue: | Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2013, ISBN 9780642278098, RRP A$49.95 |

| Exhibition website: | http://www.nla.gov.au/exhibitions/mapping-our-world |