Designing 007: Fifty years of Bond style

review by Thérèse Osborne

There are two noteworthy exhibitions showing at the Melbourne Museum at the moment, and they couldn’t be more different. In the Melbourne Gallery, Inside: Life in Children’s Homes and Institutions tells the story, largely in their own words, of the Forgotten Australians, those people – about half a million of them – who spent some or all of their childhood in the care of orphanages, children’s homes and training schools. The exhibition is sparsely populated with objects – the reason being that most of these children had nothing to show for their years of living in ‘care’. Here, it is the accounts of the Forgotten Australians themselves, graffitied, scratched, painted and splashed across the walls, that is the strength of the exhibition, and reading through these stark recollections provides a powerful, sombre and moving experience for the visitor.

Downstairs is a different story. The museum is dressed, inside and out, in black and gold, celebrating its current blockbuster drawcard. According to the introductory panel, ‘Designing 007: Fifty Years of Bond Style celebrates the skill, imagination and ambition on the filmmakers and designers who have created the look of James Bond’. And this exhibition is full of objects – so many that they are spilling out into the surrounding foyer. In fact, before you enter the spiral tunnel of the exhibition entry, you have already seen two Aston Martins, a helicopter, a parahawk, the white bikini (or a copy of it) worn by Ursula Andress when she emerged dripping from the surf, half a shark, the frozen Boris model, a whole mini-exhibition entitled Villains and Enigmas and an amusing collection of film posters promoting Bond’s international success (Leben und Sterben Lassen, Bons Baisers de Russie, El Mañana Nunca Muere, and so on). If you so desire, a bar has been set up so that you can indulge in a Bond-style martini, before or after you view the rest of the show. (This seemed quite popular on the Sunday afternoon that I attended.)

photograph courtesy the author

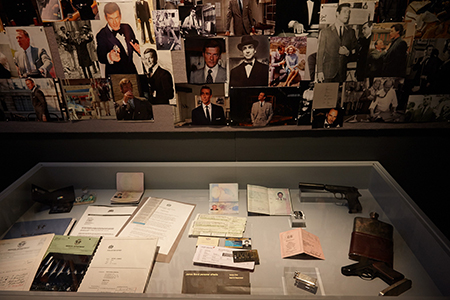

The exhibition is made up of a series of themed rooms. Some of these themes are more obviously in keeping with the exhibition’s stated preoccupation – design – than others. There is a mix throughout of costumes and film props, original set designs, storyboards and a lavish use of screens projecting selected scenes from the relevant movies. While a remarkable number of the objects are those originally used in the making of the movies, the exhibition creators found it necessary to fabricate a select few objects that no longer exist, such as, notably, Pussy Galore’s gold waistcoat from Goldfinger (1964). Some of the exhibition rooms have re-created scenes, in the form of lifesize dioramas. The first is encountered in the ‘Gold room’, where all things gold are celebrated as a nod to the 50th anniversary of Dr. No (1962), the first Bond feature movie (the exhibition first opened at London’s Barbican Centre in 2012). A surprisingly lifelike fibreglass model of Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton) smothered – literally – in gold paint and lying on a rotating bed dominates the room. Visitors then move through the ‘Ian Fleming’ room, ‘M’s office’, ‘Q Branch’, ‘Casino’, ‘Foreign territories’ and ‘Ice palace’. Of these, the least successful was the ‘Ian Fleming’ room, which was dominated by a baffling and poorly written biographical panel, but on the other hand featured a nice collection of nine first edition Bond novels with cover illustrations by Richard Chopping. This room and ‘M’s office’, which was the next room encountered, were relatively small and caused bottlenecks in the visitor flow. This was exacerbated in ‘M’s office’ by the positioning of three screens above the visitors’ heads as they enter the room, causing people to stop in the entrance way for significant periods of time. A case of ‘Bond’s personal effects’ in the corner of the room was worth the wait – assembled from various films are some excellent counterfeit identity documents: driver’s licences, passports and an American Express credit card.

©Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

‘Q Branch’ is perhaps the most popular room, and understandably so, for here is an impressive display of the gadgetry that is a defining element of the films (‘Q Branch’ being the fictional research and development branch of the British Secret Service). The room also reveals the increasing sophistication (and probably cost) of these film props. Some of the highlights (in no particular order) are Q’s ‘bag of tricks’, and a Hasselblad gun from Licence to Kill (1989), the blade-spitting attaché case seen in From Russia with Love (1963), models of a Lotus Esprit in its incarnations as car and submersible vehicle from The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), the Samsonite briefcase with diamonds and C4 explosives seen in Die Another Day (2002), Q’s acid tester ashtray from Octopussy (1983) and exploding lighter from Tomorrow Never Dies (1997). Designs for these and other gadgets are also displayed, including the design for the briefcase life raft from Moonraker (1979), while screens are interspersed with the displays, showing Q explaining the latest technology to Bond, and footage of the gadgets in use.

©Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

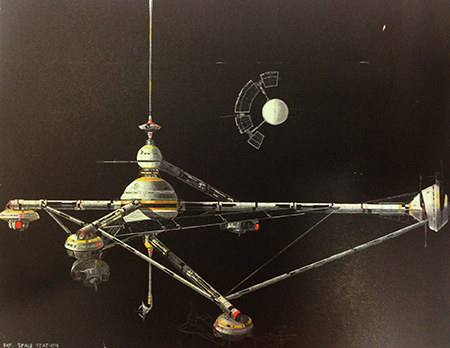

The strength of the exhibition is in this combination of original designs, footage and objects. The designs, for sets, costumes and props provide insight into the sheer amount of behind-the-scenes work in movie-making, but are often also examples of the incidental art that is created in the process. I was particularly taken with art director Syd Cain’s exquisite pencil, ink and watercolour concept for the interior of Solitaire’s occult room, in Live and Let Die (1973), and Harry Lange’s layered 3-dimensional drawing of the Drax Industries space station for Moonraker. (Lange, who had previously worked for NASA, and had also previously worked on creating the clinical and realistic spaceship interiors for 2001: A Space Odyssey, brought a striking authenticity to his set designs.) Likewise, the pencil storyboards for Octopussy, models of the sinking Venetian palazzo from Casino Royale (2006) and a striking original portrait in oils created for Live and Let Die by Ted Mitchell reveal the range of creative talent employed by the film industry.

©Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

‘Casino’ is mainly devoted to Bond fashions, and contains a central life-size diorama portraying the pivotal card-playing scene from Casino Royale, with showcases and mannequins around the edges of the room displaying clothes and jewellery, including the exquisite ‘James Bond necklace’ from Tomorrow Never Dies and the Fabergé egg from Octopussy. Most of the clothes here are those originally worn in the films, including several dinner jackets, of course, and some of the memorable dresses worn by the Bond girls, such as the beaded purple chiffon dress worn by Pam Bouvier (played by Carey Lowell) in Licence to Kill. Labels for each costume identify both the character in the film, and the actor who portrayed them, and it was nice to see a few different incarnations of James Bond (including Sean Connery, Roger Moore and Daniel Craig) represented here.

The room falls short in two significant areas. Screens along one wall display the casino scenes from the Bond movies, including the scene depicted in the central diorama. One of my fellow visitors pointed out that the figures in the diorama have been positioned in the wrong places around the table. And, while some of the most beautiful outfits from the films are on display here, the mannequins used hardly do them justice – in fact they are the most un-James-Bond-like figures I could imagine, and stand awkwardly in their elegant but ill-fitting clothes.

©Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation

The room called ‘Foreign territories’ is more successful, perhaps because attention here is firmly on the designs for exotic locations across the globe (and into space) that are another essential component of the films. ‘Ice palace’ is devoted to Bond in the snow – many famous scenes feature innovative stunts in frozen landscapes. This room contains a large model of the melting ice palace from Die Another Day, flanked by ‘ice’ sculptures of a swan, a dolphin and a perky mermaid. On three walls are huge screens showing scenes such as the ski jump from The Spy Who Loved Me, which cost a record-breaking US$500,000 to make, and that appalling scene from The Living Daylights (1987), where a cello case is used as a sled and the Stradivarius cello as a paddle. Concept drawings of the ice palace are also on display, and reveal that, at the time the film’s designers were conceiving their palace, they were also taking into account exactly how it would ultimately be destroyed.

I suppose my overwhelming impression is that the attention to detail lavished on the design and creation of the Bond films is not matched by the design and presentation of this exhibition. I was particularly disappointed with the wall text. The larger text panels are awkwardly written and punctuated, while the smaller object labels are in tiny print, often unlit and unreadable. There are inconsistencies in spellings (‘Casper’ and ‘Caspar’ appear on the same panel), and it is clear that an editor was not employed either in the making of the exhibition, or the development of the exhibition catalogue – I was particularly taken by the sentence: ‘Iris Rose … soon revealed the magnanimity of the task I had taken on’ (p. 9).

The exhibition’s creators make some grand statements about the significance of the style and design of the Bond films – ‘over time, Bond films have resonated beyond cinema … influencing half a century of design and technology’. This claim is not really proven. The films can perhaps claim the first digital watch and mobile phone remote control to be seen on the big screen, but I suspect their influence on the development of such technology does not really go beyond first mentions. In fact, the sheer escapism of the films implicitly counters their potential influence on the real world, the fashions are classic rather than cutting-edge and the latest film, in particular, conveys a nostalgic, backward-looking storyline that is overtly ‘anti-technology’. Certainly, the film producers’ liberal use of product placement in cars, couture, alcohol, cigarettes, cameras, etc. is an indication of Bond’s influence on consumer buying habits. But this is not really discussed in the exhibition. In any case, the whole display seems to be far more about celebrating 50 years of James Bond movies than providing evidence of how the films have influenced mainstream design and culture.

For all my grumblings, I enjoyed my visit to Designing 007. The keepers of the Bond archive are to be commended for compiling and caring for such a rich archive that spans more than 50 years and contains this diverse range of material. The films, and this exhibition, are a lot of fun. But at the end of the day, the story, told and retold, of a laconic but honourable hero’s fight against villains with an insatiable appetite for evil, the lavishly contrived action, high-budget stuntwork and general derring-do serve to keep the audience in a happy state of suspended disbelief. I hope that Designing 007 will attract a new audience to the museum, and that these visitors will also be enticed (because the ticket price includes entry to all the exhibitions on show), to some exhibitions of a more profound and educative nature – once they’ve finished their martinis, of course.

Thérèse Osborne is a co-editor of reCollections: A Journal of Museums and Collections.

| Exhibition: | Designing 007: Fifty Years of Bond Style |

| Institution: | Barbican Centre, London, and EON Productions |

| Curators: | Bronwyn Cosgrave and Lindy Hemming |

| Exhibition design: | Ab Rogers |

| Graphic design: | Praline |

| Venue/dates: |

Melbourne Museum, 1 November 2013 – 23 February 2014 |

| Exhibition catalogue: | Bronwyn Cosgrave, Lindy Hemming and Neil McConnon (eds), Designing 007: 50 Years of Bond Style, Barbican International Enterprises, London, 2012, ISBN 9780957326200 (paperback) |

| Exhibition website: | Designing 007 Melbourne Museum |

Related link

Exhibition review of Inside: Forgotten Australians, reCollections vol. 8 no. 1