Handwritten

Ten centuries of manuscript treasures from Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

review by Robert Nichols

We live in an age in which the handwritten word is under threat. Writing in the Australian recently, Christopher Bantick predicted that 'handwriting will eventually die out as a form of communication' and deplored the requirement that schoolchildren persist in the outmoded practice of using pen and ink. Nowadays many of us only put pen to paper when marking up computer printouts or jotting down a hurried shopping list. But even those who feel that handwriting is a skill no longer required in the age of the keyboard and touch-screen can surely revel in the fascinating array of handwritten manuscripts gathered together in the National Library of Australia's latest blockbuster. The core of this exhibition comprises treasures drawn from the extensive collection given to the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin in 1907 by Ludwig Darmstaedter, industrial chemist, historian of science and, clearly, indefatigable collector.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz

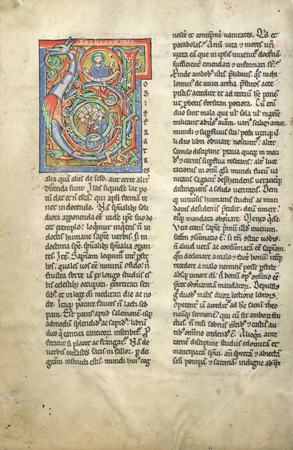

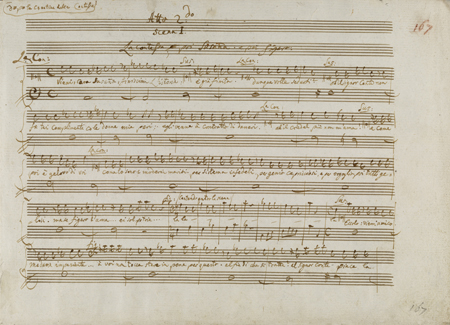

The exhibition is divided into three parts: the first room contains a beautiful series of medieval and renaissance manuscript books, such as a stunning thirteenth-century Paris Bible, whose intricate script and illustrations make you wince at the thought of the damage creating it must have done to the anonymous scribes' eyes. The main display area features items from an amazing range of scientists, writers, politicians and philosophers: Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo; Darwin, Curie and Einstein; Napoleon, Machiavelli and Bismarck; Dickens, Mann and Kafka; Descartes, Kant and Nietzsche — one begins to wonder whether anyone of note from the past half millennium has been omitted. The final room contains a series of handwritten musical scores by composers such as Bach, Haydn, Wagner and Mahler. It is interesting to be able to compare scores by Mozart and Beethoven: the score of the Marriage of Figaro seems to display the effortless creativity we associate with Mozart. By contrast, Beethoven's score for the Fifth Symphony bears the unmistakeable signs of a working manuscript, its riot of corrections calling to mind the popular image of this tempestuous Romantic.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz

There are delightful surprises to be had wherever you look: the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant, author of the fiendishly abstruse Critique of Pure Reason, is represented by a letter to a mineralogist in which Kant expresses his interest in mining. Another German philosopher, the ever irascible Arthur Schopenhauer, is represented by a first edition of his essay On the Will in Nature, the pages of which are almost overwhelmed by his obsessively detailed marginal corrections and annotations. Schopenhauer has been aptly placed at some remove from his great contemporary, GWF Hegel, whom he famously detested. Schopenhauer purposively scheduled his lectures for the same hour as those of his rival. Students flocked to Hegel's class, but Schopenhauer secured only a handful of listeners — and soon lost even those. It is sometimes claimed — and knowing the man's character one readily believes it — that he continued to lecture to an empty hall.

Everyone will of course discover their own favourite piece: mine is a diminutive diary kept by Peter Hagendorf, an obscure German mercenary who fought in the Thirty Years War. In its pages, the label informs us, Hagendorf reflects on Westphalia's 'good old beer as well as bad people', notes seeing seven people, including "a beautiful girl of eighteen", burned to death, and offers instructions on how to bake pumpernickel. Elsewhere, he recounts the occasion on which he was shot through the belly and both shoulders.

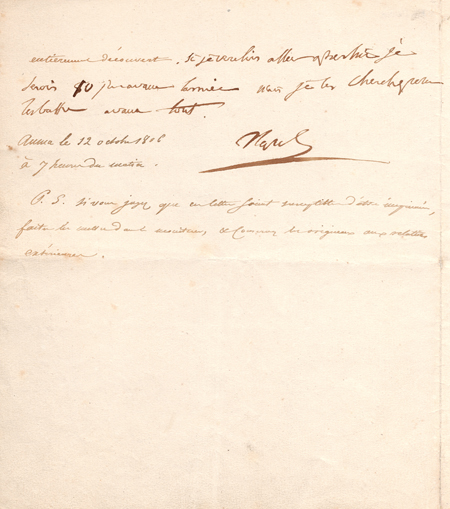

The exhibition labels are kept mainly on the short side, and this is very much to be applauded. They give just enough information to place the excerpt in its context but without threatening to overwhelm the item itself. And yet the labels often find space for the telling detail. The one for a letter Napoleon sent to his foreign minister, the wily Talleyrand, records that Napoleon once described him as 'dung in a silk stocking'.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz

Just occasionally one is frustrated by not being told the detail one wants to know. The label for the oldest manuscript in the exhibition, some fragments from a ninth-century copy of Virgil's Aeneid, for example, informs us that they are written in Carolingian minuscule, a new rounded script that resulted from Charlemagne's efforts at educational reform. Good to know, but I had hoped for some explanation of the intriguing interpolations scattered between the poem's lines.

In the centre of the main room are various helpful features: iPads allow visitors to look up Wikipedia, consult the exhibition blog — or presumably check their email. There are large-print copies of all the exhibition text, and also flipbooks that give what purport to be full 'transcriptions' of the documents from which the excerpts on display have been taken, though in many cases they are in fact translations.

Although rewarding to inspect, the collection of musical scores is less successfully displayed. Almost inevitably, directional speakers have been placed over each showcase. But unfortunately the sound quality is very poor; even worse, each piece of music is forced to compete with leakage from the other speakers, so that the overall experience is more irritating than satisfying. Near the exit is a wall-mounted iPad, which the visitor can use to listen to any of the pieces. This is a better option, but even here it is hard to ignore the ambient low-level cacophony.

In an exhibition that offers so much it is churlish to regret omissions, though it is slightly surprising that there is nothing from Hitler's hand. An institution is of course constrained by the limitations of its holdings, but it is difficult to conceive that nowhere in the Staatsbibliothek is there a scrap of paper with the Führer's writing on it.

In what is perhaps a sign of things to come, the last document in the exhibition is a typewritten page by the poet Joho in which the handwritten element is just a two-word insertion. Yet even here the reason for this exhibition's success is clear. There is an ineffable seductiveness in finding oneself so close to the almost tangible marks made by so many famous — and not so famous — men and women. It is an experience not to be missed.

Robert Nichols is senior editor at the Australian War Memorial. He wrote this review in longhand — just in case.

| Exhibition: | Handwritten: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Treasures from Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin |

| Institution: | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and National Library of Australia |

| Curatorial team: | Eef Overgaauw, Gabriele Kaiser and Martina Rebmann, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin; Nat Williams and Susannah Helmann, National Library of Australia |

| Exhibition design: | Uli Lechtleitner and Thomas Wolter, buerozentral.architekten, Berlin; Isobel Trundle, National Library of Australia |

| Blog: | http://blogs.nla.gov.au/handwritten/ |

| Catalogue: | Handwritten: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Treasures from Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2011 |

| Venue/dates: | National Library of Australia, Canberra, 19 October 2011 – 18 March 2012 |