Traversing Antarctica

The Australian experience

review by Alessandro Antonello

One hundred years ago Douglas Mawson and the men of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition set sail from Hobart for Antarctica. They landed at Commonwealth Bay on 8 January 1911, establishing not merely a base, but making the first specifically Australian place upon the ice. Despite earlier Australian encounters with the region, this act of settlement is being marked as the beginning of a century of a deep and sustained connection with the Antarctic. Engaging directly with these centennial celebrations is Traversing Antarctica: The Australian Experience, a travelling exhibition created by the National Archives of Australia in collaboration with the Australian Antarctic Division and the Western Australian Museum, and opening first at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart.[1]

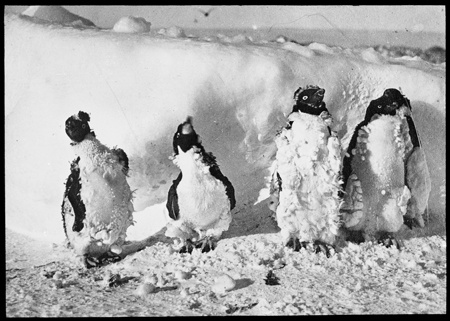

photograph by Frank Hurley

National Archives of Australia, NAA: M584, 6

The exhibition is about Australia's political and scientific experience of the Antarctic over the last century. The story is told through the seminal moments in that history, the major, Australian-led expeditions that undertook science, exploration and territorial acquisition: the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) of 1911–14, led by Douglas Mawson; the British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Expedition (BANZARE) of 1929–31, also led by Mawson; and the continuing Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) after 1948, under various leaders from the Australian Antarctic Division.

photograph by Gilbert Herrada

National Archives touring exhibition at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

photograph by Gilbert Herrada

National Archives touring exhibition at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

photograph © Chris Wilson

Australian Antarctic Division

photograph by Gilbert Herrada

National Archives touring exhibition at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

Nevertheless, there is a strong sense of direction within the exhibition, and the quality is heightened by excellent interpretive panels. Writing interpretive panels is a demanding art; curator Jane Macknight's panels are informative, concise and clear.

The physical encounter with Antarctica often dominates our understanding and narratives (and this exhibition offers an ice sledge and a husky, somewhat superfluously, as examples of that physical encounter), yet it is letters, telegrams and proclamations that necessarily dominate this exhibition. These textual records are carefully chosen and well deployed to tell the story. Most importantly, using these government records helps to reconfigure our appreciation of Australia's encounter with Antarctica, insisting on the equally consequential intellectual and bureaucratic labours that come before and after the brief physical encounters with the continent.

photograph by Gilbert Herrada

National Archives touring exhibition at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

Yet, while I appreciate the insistence on these documents, such a text-heavy exhibition can afford greater curatorial intervention. Often texts are treated as equivalent to objects: they are simply placed in the display for the viewer to consider. Yet a government record, though its materiality can be important, is important for its written contents. For example, part of the report of the 1926 Imperial Conference is presented. It was at this conference that the governments of the British Empire agreed that the Antarctic should be overwhelmingly British (making accommodations for France and Norway). Over two pages is a lengthy text, printed in small type, detailing this Imperial policy. Could a better effort have been made to draw the viewer's attention to the choice phrases, while leaving the more engaged and committed visitor to read the whole text?

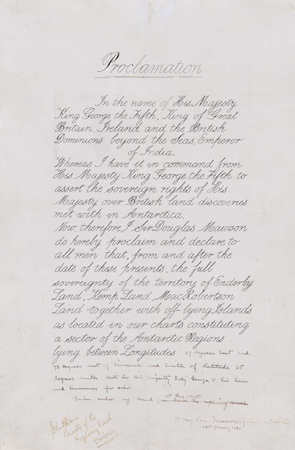

And then there are those documents that are physically relegated to inconspicuous places where they surely do not belong. The one document that should have been more prominently displayed in this exhibition is the Proclamation made by Douglas Mawson in February 1931 taking possession of parts of Antarctic for the British Crown — one of several he made during BANZARE. This document is the culmination of the earliest desires and efforts of Mawson and other scientific and political worthies of his time; it is a foundational document of the Australian Antarctic Territory. Yet the visitor finds it in the bottom drawer of a module. Undoubtedly the document demands careful conservation (doubly so because of its legal importance), but given the major theme of this exhibition, why was it made so inconspicuous?

National Archives of Australia, B1759, MAWSON B

photograph by Frank Hurley

National Archives of Australia, NAA: A4311, 365/9/3

The visitor's traverse of this exhibition ends indeterminately. After the strong narrative of the first section leading to the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, the visitor is flung across the decades to the modern concerns for ecosystems, climate science and environmental protection. There is little finality: diplomatic work within the Antarctic Treaty System will continue, but there are challenges ahead; scientific work continues unabated as we race to understand and fix our global ecological crisis. By emphasising the politics of our Antarctic history, this exhibition challenges the public to consider Australia's Antarctic future. Do we go south for ourselves or for the world?

Alessandro Antonello is a doctoral candidate in the School of History, Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University, and is researching the diplomatic, environmental and scientific history of the Antarctic after 1945.

| Exhibition: | Traversing Antarctica: The Australian Experience |

| Institution: | National Archives of Australia |

| Lead curator: | Jane Macknight |

| Lead designer: | Daniel Schoknecht, Western Australian Museum |

| Venue/dates: | Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery 1 December 2011 – 26 February 2012; National Archives of Australia, Canberra, 23 March – 9 September; travelling to Western Australia, South Australia and other venues |

| Website | www.naa.gov.au/visit-us/exhibitions/traversing-antarctica/index.aspx |

Endnotes

1 I would like to declare that during early development of this exhibition I took part in discussions between Jane Macknight (Curator, National Archives of Australia), Tom Griffiths and Marie Kawaja (both of the School of History, Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, and consulting historians to the exhibition).

2 The most recent work in this vein is Ellie Fogarty's policy brief, 'Antarctica: assessing and protecting Australia's national interests', Lowy Institute, Sydney, August 2011, www.lowyinstitute.org/Publication.asp?pid=1661.