A new horizon

Contemporary Chinese art

review by Caroline Turner

A New Horizon: Contemporary Chinese Art, a collaborative project between the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) in Beijing and the National Museum of Australia in Canberra, was shown at the National Museum from 30 September 2011 to 29 January 2012 as part of an Australian Government cultural diplomacy initiative, ‘Experience China: The Year of Chinese Culture in Australia’. The exhibition, which attracted nearly 40,000 visitors, followed the National Museum’s very successful presentation at NAMOC in 2010 of an exhibition of Aboriginal art that attracted 125,000 visitors (Papunya Painting: Out of the Australian Desert).

A New Horizon offered 76 works from the past 60 years in a variety of media, including sculpture and a 3-D animation. The themes covered were varied with a strong emphasis on genre and nature but there were also portraits and abstraction. The stated aim was to provide a ‘window into the development of Chinese contemporary art’. Covering the extraordinarily tumultuous period from the victory of Communism in 1949, the 10 years of the Cultural Revolution beginning in 1966, China’s rapid economic and urban growth after Deng Xiaoping’s open door policy in 1978 to the present, with all the changes in art and art discourses in that period, was clearly an impossible task. It would need a far larger exhibition to attempt this. The curators therefore chose a specific focus.

by Lin Fengmian

National Art Museum of China

Director of NAMOC, Fan Di’an, explained in his foreword to the catalogue that the challenge was ‘to bring to the Australian public a different perspective on Chinese contemporary art than had previously been displayed in Australian cultural institutions … we decided to create an exhibition featuring Chinese art since 1949, one that located Chinese art in the context of social and political change’.

Andrew Sayers, Director of the National Museum of Australia, noted that it was his suggestion to focus on the early period because, while Australian audiences have become familiar with the art of the present in China, ‘the art of China in the decades from the 1950s to the 1980s is not as well known’.[1]This was an interesting decision on Sayers’ part and, without question, the particular strength of the exhibition is from 1949 to the early 1990s. One visitor in his 20s to whom I spoke remarked this exhibition was a revelation to those in his age group in understanding China in that era.

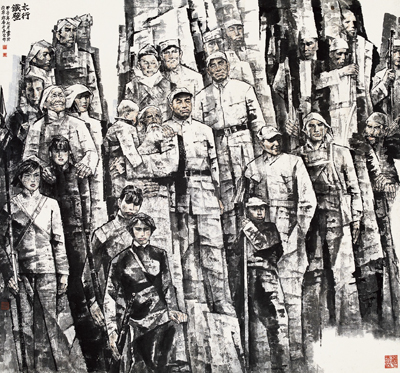

Sayers makes the additional point that the exhibition has many examples of works that had a major impact in China when first exhibited and key works by artists in influential positions in teaching institutions. One example is the haunting ink-and-wash painting of revolutionary leaders by senior wife and husband team Wang Yingchun and Yang Lizhou (a former Director of NAMOC). Taihangshan Steel Wall (1984) is, as the catalogue tells us, considered a ‘masterpiece’ in Chinese recent art and symbolises ‘the resilience of the Chinese people’. Overall this was very much an exhibition of art considered important in China.

by Wang Yingchun and Yang Lizhou

National Art Museum of China

The exhibition was divided into three sections: ‘New China’ (1949–77), ‘New thinking’ (1978–99) and ‘New century’ (2000–09). Chinese modern art developed after the overthrow of the Imperial Dynasty in the Revolution of 1911. Chinese artists began to travel and study abroad and Western oil painting was introduced into the art academies. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 the role of art was defined as being to ‘serve the people’. Socialist realist styles were adapted from the Soviet Union. Traditional art styles, especially ink-and-wash painting, continued and the exhibition contains many fine examples, including Red Lotuses (1951) by Qi Baishi, an artist whose career spanned the Qing Dynasty, the Republic and the Communist era, and whose works now command extraordinary auction prices.

National Museum of Australia

In his public lecture, Fan Di’an suggested that while some have described art since 1949 as under the control of ideology, much was a genuine depiction of the hopes of the new nation. An example cited was Sun Zixi’s Group Photo at Tiananmen (1964). It depicts ordinary Chinese, now the ‘masters of the nation’, posing in front of what was once the main gate of the Imperial Palace. Many other works in the early period do transcend ideology, as in Pan He’s bronze Hard Times (1957), showing a barefoot young soldier listening to the flute played by an older comrade.

by Pan He

National Art Museum of China

The propagandist kitsch of the Cultural Revolution, however, is evident in Zhou Shuqiao’s Spring Breeze and Willow (1974), presenting a joyous bunch of young intellectuals from the cities arriving in a village, to be re-educated by the peasants. The catalogue tells us that the title refers to new beginnings.

by Zhou Shuqiao

National Art Museum of China

by He Duoling

National Art Museum of China

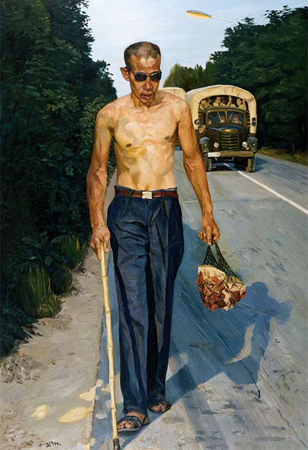

Cheng Conglin’s Snow xx 1968 (1979) is also the antithesis of Spring Breeze and Willow andemerged from the time when the Cultural Revolution was repudiated. The title is the same as that of a much-discussed poem of Mao’s on the theme of history and heroes. It shows a violent urban street fight between youth during the Cultural Revolution. Other strong works reflecting the drama of the human condition include Liu Xiaodong’s Blind (1994), depicting a thin, shirtless blind man feeling his way along the road with a truck of cheerful passengers coming up behind him. One is left to speculate whether their intention is to help, ignore or jeer him.

by Liu Ziaodong

National Art Museum of China

Xu Jiang’s Big Beijing-Old Wall (2001) is an especially powerful treatment of historical landscape. Wang Yan’s Chicken Feast (2005) can only be a bitter exercise in irony, with its study of a farming couple beneath a dark sky with a city in the background, heartbroken at having to burn their chickens and thus destroy their livelihood, presumably to resist the spread of avian flu. This contrasts with the many artworks in the exhibition inspired by nature or exploring inner worlds, such as, for example, the lyrical and poetic Girl Leading a Horse (1999) by Wang Lan, an artist now living in Australia.

National Museum of Australia

The largest painting, and for me the highlight of the exhibition, is Shen Jiawei’s Red Star over China (1987), inspired by the book of the same title by Edgar Snow, first published in 1937.

National Museum of Australia

Shen has spoken movingly on his motives for undertaking the work after reading a banned copy of Snow’s book. He emigrated to Australia in 1989 and has made a major reputation here as well as in China. The painting depicts almost everybody involved in the direction of the early Communist Revolution, comprising, in Shen’s terms, some ‘104 real historical persons’. There are some absentees, namely those who had lost favour in the eyes of the authorities, in particular Hu Yaobang. Shen asserts that ‘what is painted here is the first act of a tragedy. The fine quality, beauty, youthfulness and ideals will be destroyed by later acts which are yet to be painted’.[2] The most intriguing aspect of this enormous painting must be the positioning of Mao, as an equal not as a ‘demigod’, seemingly even dilettantish, cigarette nonchalantly in hand, dressed informally and behind the heroically commanding figure in military uniform of Zhou Enlai.

by Shen Jiawei

National Art Museum of China

In his brilliant study In the Red Geremie Barmé notes the clash between official culture and many intellectuals, artists and dissidents in China since the late 1980s.[3] Missing from the last section of the exhibition were various movements from the late 1980s to the present such as the satirical social and political criticism of the 1990s ‘Mao Goes Pop’ artists or the often raucously irreverent offerings of the liumang (‘hooligan’) artists. I would also like to have seen more art challenging boundaries and reflecting contemporary social change and intellectually profound works confronting memory and history, such as Yang Fudong’s films or art exploring the legacy of the Cultural Revolution, for example by Zhang Xiaogang, who explored idealism in the service of ideology in his androgynous paintings of young people wearing Mao suits and with utterly blank faces.

Although such works have been shown previously in Australia, their inclusion would have contributed to the theme of ‘social and political change’. There is no doubt, however, that the exhibition served to extend our awareness of the enormous range of Chinese contemporary art and was well received by visitors.

The enthusiastically attended public programs accompanying the exhibition included the lecture by Fan Di’an, a major conference organised by the Australian National University’s Australian Centre on China in the World and children’s art workshops. Although the National Museum of Australia’s temporary exhibition gallery provides rather cavernous dark spaces, the display of the exhibition was good but would have benefited from more information available to visitors on both the art and history, such as computers within the show or an audio guide to supplement the very short introductory wall panels.

This was an important exhibition demonstrating a commitment by the National Museum of Australia to displaying the culture of our Asian neighbours and art as a means of enriching our understanding of history and social change.

Caroline Turner is a senior research fellow in the Research School of Humanities and the Arts, Australian National University, a former member of the Australia–China Council and project director of the Asia-Pacific Triennial exhibitions in the 1990s.

| Exhibition: | A New Horizon: Contemporary Chinese Art |

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia and National Art Museum of China |

| Curatorial team: | Andrew Sayers, National Museum of Australia; Fan Di’an, Ma Shulin, Yi E, National Art Museum of China |

| Exhibition design: | Thylacine Design and Project Management |

| Graphic design: |

Po Sung, National Museum of Australia; Wei Feng, Zhang Chao, National Art Museum of China |

| Venue/dates: | National Museum of Australia, Canberra, Australia, 30 September 2011 to 29 January 2012 |

| Catalogue: | A New Horizon: Contemporary Chinese Art, National Art Museum of China and National Museum of Australia, Beijing and Canberra, 2011, A$29.95 |

| Webpage: | www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/a_new_horizon/home |

Endnotes

1 Major exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art seen in Australia include: New Art from China: Post-Mao Product, curated by Claire Roberts (1992); the six Asia-Pacific Triennial exhibitions beginning in 1993; The China Project, curated by Suhanya Raffel at the Queensland Art Gallery (2009); Mao Goes Pop: China Post-1989, Museum of Contemporary Art (1993); the Sydney Biennale from the 1990s; Inside/Out: New Chinese Art, Asia Society New York, shown at the National Gallery of Australia (2000); exhibitions at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art over two decades; exhibitions at the Sherman Foundation; and the forthcoming exhibition of Chinese portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in 2012.

2 Artist statement 2011 available as a handout in the exhibition.

3 Geremie R Barmé, In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture, Columbia University Press, New York, 1999.