Sin city

Crime and corruption in 20th-century Sydney

review by Stephen Robertson

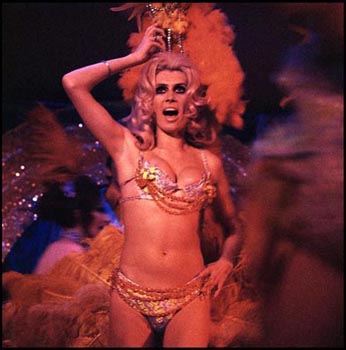

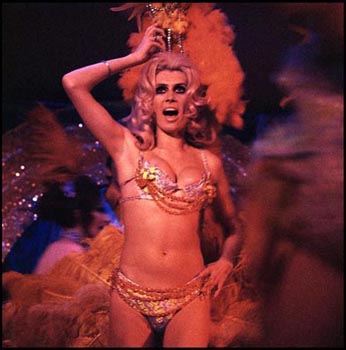

Carlotta, Les Girls, Kings Cross

Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

Historic Houses Trust

In promoting the

Sin City exhibition, curator Tim Girling-Butcher spoke frequently of how Sydney is a place with no recollection of its past as one of the most corrupt cities on the planet, rife with organised crime. I've lived in Sydney for only ten years, and I spend my time studying American history rather than Australian history, but I've certainly been conscious of the sordid past of the city and its police, and the reputation of Kings Cross in particular. It seems even less likely that my fellow Sydneysiders do not think of their city's past in these terms since the

Underbelly television franchise that came to town in 2010. The 13-part mini-series on the nightclub scene in Kings Cross in the late 1980s and 1990s,

Underbelly: The Golden Mile, drew over two million viewers in Australia's capitals, including more than 700,000 in Sydney. Sin City opened a matter of weeks after the premiere of the series. Although not as much of a surprise as Girling-Butcher claims, the exhibition offers aficionados of crime a story different from the series, beginning in the 1920s but concentrating on the 1960s and 1970s.

It is appropriate that entering the exhibition takes you into a darkened room — many of the illegal and underhand activities whose policing is the subject of this exhibition took place in small, poorly lit spaces. The long rectangular room in the eastern wing of the museum, formerly home to the court's clerical staff, provides most of the exhibition space, together with a small square room across the corridor, once the Magistrates Room. As you enter the main room, a light box on your left offers brief descriptions of the vice trades operating in twentieth-century Sydney: bookmaking, prostitution, drugs, sly grog and illegal casinos. To the right is a space set up like a 1960s nightclub, with authentic fixtures and displays of strippers' costumes, and tables facing a large screen flanked by two smaller screens. Stretching much of the length of the opposite wall is a timeline of organised crime and legislation, a 'Century of crime'. Beyond the nightclub is a small area devoted to illegal casinos, with a collection of confiscated objects, slot machines and a blackjack table.

Costumes belonging to go-go dancer Elizabeth Burton

photograph by Jenni Carter

Historic Houses Trust

As this layout suggests, the centrepiece of the exhibition is a video presentation. It mixes interviews, television footage, and newspaper coverage to tell a story of changing vice activities, criminal kingpins and corruption. The presence of American servicemen in Sydney was pivotal to how sin unfolded in the town, particularly as customers for sly grog during the Second World War and later, during the Vietnam conflict, as consumers of heroin and marijuana. The money that fuelled corruption came from illegal bookmakers and casinos. As the focus of the documentary shifts to corruption, it increasingly relies on interviews with former police officers, undoubtedly appropriate to the focus of the museum, but providing a narrower perspective than the overall framing of the exhibition led me to expect. Coupled with the focus on criminal kingpins and investigative journalists, it tends to reduce the story to one of individuals, many of whom come across as larrikins and larger-than-life figures, whose identities are neither explained nor contextualised. That is exactly how individual personalities are presented in the second room, whose walls are covered with a series of almost lifesized, visually striking images, each accompanied by a pithy quotation and brief biographical information. When the exhibition reaches for broader explanations, it points to restrictive legislation, laws limiting the opening hours of hotels, and the banning of gambling, drug use and street solicitation by prostitutes. Again, although it is perhaps inevitable that a Justice and Police Museum would take this focus, many places in Australia and abroad shared similar legal frameworks in these years, making it a less than entirely satisfactory argument for an exhibition premised on the idea that Sydney had a particular reputation for vice.

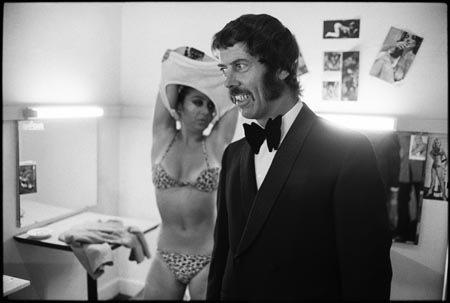

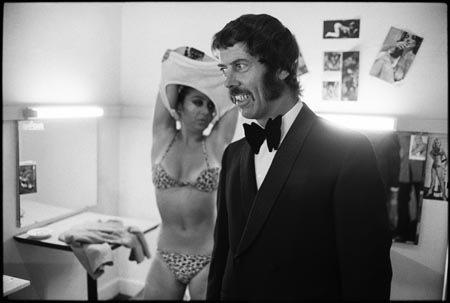

MC, Paradise Club, Kings Cross

Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

Historic Houses Trust

The exhibition also fails to clearly locate the story of vice activity within the city itself. I almost walked right by the one display that hints at this missed opportunity. Near the exit from the large room to the second room of the exhibition space is a small map showing the location of three illegal casinos in Kings Cross. In the short book published to accompany the exhibition, Girling-Butcher gives population growth and an exodus to the suburbs equal standing with restrictive legislation in explaining the development of organised crime, but, in the documentary, population and place quickly drop away as legislation and policing become the focus. Mentions of Kings Cross recur, and the fight over the development of Victoria Street occupies centrestage for some time. But there is no effort in the documentary or elsewhere in the exhibition to show where Sydney's vice was concentrated, or even provide a map of the different and changing vices found in Kings Cross, other than the street map I almost missed.

So central is the video to the exhibition that I found myself asking what the museum offers as a setting for watching the documentary that my living room does not. The nightclub space is certainly evocative (although I could find nothing explaining or describing the setting and its fixtures). However, visitors who take a seat at one of the tables do not see what a nightclub patron would have seen, and in that sense the replica setting and the documentary are somewhat at odds. The objects related to illegal gambling, by contrast, give a welcome materiality to the story, complementing the video and adding some historical specificity to activities that still feature in contemporary Sydney. The second room provides access to the sources on which the video is based, namely an archive of news clippings. This display functions in a similar way to the websites that now commonly accompany television documentaries; even the means of accessing the material is the same, with two large monitors in the centre of the room. The clippings are displayed in an attractive interface that shows the stories in a strand through which the visitor can scroll and select stories to be enlarged and read. This archive would clearly reward sustained exploration, although I can't help but wonder just how many visitors know where to start, even after watching the documentary. Moreover, the quantity of material far exceeds what most visitors would want to engage with during their time at the museum — which makes it more suited to online display.

Ultimately, while the physical displays that surrounded the video presentation enriched the story told in the documentary, they occupied a fraction of the time I spent sitting in front of a screen. Nonetheless, it's the objects and settings that remain with me — as do the courtroom, cells and police charge room elsewhere in the Justice and Police Museum — leaving me disappointed that Sin City did not devote more attention to material culture.

Stephen Robertson is an associate professor of history at the University of Sydney, currently researching everyday life in 1920s Harlem, and developing Digital Harlem.

| Exhibition: |

Sin City: Crime and Corruption in 20th-Century Sydney

|

| Institution: |

Historic Houses Trust |

| Curator: |

Tim Girling-Butcher |

| Venue/dates: |

Justice & Police Museum, Sydney, 1 May 2010 – 22 May 2011 |

| Catalogue: |

Tim Girling-Butcher, Sin City: Crime and Corruption in 20th-Century Sydney, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2010, RRP A$19.95 |