Vanquished by forbidding cold, fierce winds and chilling ice, Scott's last expedition has long been the ultimate tragic tale. Amid the early twentieth century scramble for Antarctica, Robert Falcon Scott and his four fellow expeditioners did reach the South Pole, but not before Roald Amundsen and his team. Then they almost made it back to safety, but perished after completing over 90 per cent of the return journey. Nearly a century later the frozen fate of these men is still the stuff of legend, even factoid, in popular imagination. The famous last words of Lawrence Oates ('I am just going outside and may be some time'), so often misquoted, reverberate not just because the ice consumed him, but also because the man who uttered them vanished, his body perhaps never to be found.

Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge

Scott's Last Expedition tells different and more compelling stories. This travelling international exhibition produced by an evidently fruitful collaboration between the Natural History Museum, London; the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch; and the Antarctic Heritage Trust, New Zealand is on our shores at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney. Eschewing the traditional tragic narrative arc, the exhibition captures something of everyday life during this expedition, detailing the herculean labours and logistical contortions undertaken by so many between 1910 and 1913 to make it happen. Most importantly, it humanises the almost cybernetic heroic characters of legend. By the end of the exhibition, an engaged and attentive viewer is likely to be struck with a more profound sadness at Scott and his companions' fate.

Not that the exhibition ignores the tragic. At the very beginning, the viewer is confronted with Scott's impending end. His last (written) words are enlarged on a clear white panel: there is no chance then of misreading them, as could happen deciphering the script in the actual diary. There is also no chance of misinterpreting them. They are the words of a man who is not only dying, but who also knows that he will soon be dead. They are the words of a man conscious of his legacy and who, understandably, knows that the efforts and endurance of his team will certainly perish unless he writes of them. They are words that speak of how early twentieth-century European culture valorised courage, endurance, bravery and sacrifice.

Next we see copies of the Captain Scott Memorial Edition of England's Daily Mirror, from 1913, as well as initial reports of Scott and his companions' demise. Here the viewer discovers, through hard copies of the newspaper and explanatory panels, how the world learned of this disaster and how the story and the legend took shape. Using excerpts from Scott's diary, disaster became a tale of grit and stoicism. Heroism was privileged over suffering, no doubt catering to the needs of late imperialist sensibilities. But this template has long denied Scott and his companions the humanity of their suffering. This is the story that many, if not most, visitors to the exhibition are familiar with, so showing how it was originally constructed is an excellent departure point for this exhibition.

The context provided for the last expedition is helpful. A video shows images of the beauties and ravages of Antarctica and gives a sense of the half-year-long days and half-year-long nights. Those who do not know learn through panels and maps that sketch the earlier history of European and neo-European exploration of Antarctica: Cook, Bellingshausen, Ross, right through to Scott's first expedition (1901–04) and Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition (1907–09).

With the story switching to Robert Falcon Scott's life and earlier expedition, the exhibition focuses more on the personal and material. Scott's medal, sword, navy bicorne hat and some of the supplies — an orange Huntley and Palmer's biscuit tin, a green-and-gold Lyle's golden syrup tin and a packet of Tate sugar cubes — are all arresting to a viewer in 2011. They also remind us that these heroes were men who needed clothing and food, and who had been honoured for deeds before this fatal expedition. Accompanying panels inform some and remind others that corporate sponsorship is not new and that many organisations and people in England were to varying degrees connected with both of Scott's expeditions.

Similarly, we learn of the serious, abiding scientific effort of these expeditions. In particular the involvement of eminent institutions such as the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society is highlighted. This emphasis on connections with other groups and other people is a welcome departure from the popular notion of such expeditions being undertaken by a superhuman leader and his band of merry men.

A complete list of all who ventured on Scott's last expedition is provided. The ship's crew, as well as the shore party, are all named. Intricate plan drawings of the Terra Nova illustrate something of the structures of life on the seas for its crew. There is also a fascinating list of the food the expeditioners took with them: 100 tins of giblet soup, 90 kilograms of bacon, 150 bottles of anchovies, 48 bottles of sherry ... the list goes on. Details of other equipment, such as meteorological instruments, tools and board games are also listed. A map illustrates the route of the voyage, complete with key dates. Artefacts of the scientific work undertaken en route include a Herald petrel, coral and detailed botanical and topographical sketches.

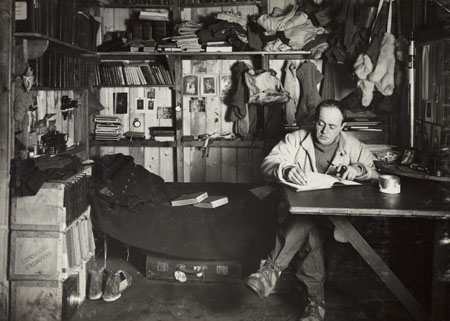

The replica of the Cape Evans hut is the highlight of the exhibition. I won't say too much about it, lest I spoil the experience for any prospective viewers. This 'to scale' representation of the expedition's Antarctic base offers an engaging window into everyday life for the men who were there. Lines on the floor mark out where each man slept. Photographs show both how cramped these spaces where and how homely some of the men made them. A copy of the South Polar Times, which recorded the artistic and literary life of the shore party, copies of Kipling's Actions and Reactions and a biography of Robert Burns, all adjacent to a playing Monarch Senior gramophone tell us that they were men of culture as well as action. Many other objects, as well as clever use of video projections, tell us how the shore party used this space — how they lived, how they worked — and something of how they interacted with each other. From this material it is not hard to imagine the contrast between the warmth inside and fierce cold outside: the thermal warmth afforded by the walls, the emotional warmth of conviviality and the heat of inevitable conflict. That this was what Scott and his companions almost returned to makes this exhibit all the more poignant.

Pennell Collection, Canterbury Museum, New Zealand

Stepping out of the hut, the display of the woolly mammoth-like garb of Scott and his companions reminds us just how cold it was for them on their journey to the South Pole and back. As with earlier sections of the exhibition, the displays of the men's equipment — ski boots, sleds, lamps, dog harnesses, Osman's dog collar, etc. — as well as the information provided on the panels, are exemplary. The interactive display of electronic extracts from Scott's diary is particular absorbing. More broadly, the videos speaking of the significance of the expedition today are also worth viewing.

Indeed, there is little to fault in this exhibition. The range of objects, the use to which they are put and the stories they tell are invariably engaging. The contextual and explanatory information is useful and of high quality. Those who know little about Scott's last expedition can learn a lot. The already knowledgeable are likely to appreciate the attention to detail, the volume and range of objects and the varied stories they and the commentaries tell. This exhibition aims to reach everybody. There is worthwhile supplementary material on the Maritime museum's website, a book and even a children's colouring book. My only reservation is that some of the vital, if understated, material towards the beginning can get a little lost in a corridor that has a number of entrances/exits. Given the obvious spatial constraints the layout is a reasonable compromise and, after all, the exhibition is easy to navigate.

The exhibition ends where it began, with Scott's last words. It is an exhibition that especially rewards attentive engagement. Like TS Eliot's 'explorer', the attentive viewer will likely arrive at this 'beginning' with a very different understanding of its meaning and, dare I say, know it 'for the first time'.

Chris O'Brien is a PhD candidate in history, in the School of Environmental History at the Australian National University, working on a history of weather and climate in Northern Australia.

| Exhibition: | Scott's Last Expedition |

| Institution: | Natural History Museum, London (UK), Canterbury Museum, Christchurch (NZ) and the Antarctic Heritage Trust New Zealand |

| Curator: | Elin Simonsson, Natural History Museum, London |

| Floor space: | 600 square metres |

| Venue/dates: | Australian National Maritime Museum, 17 June 2011 – 16 October 2011 |

| Catalogue: | Steve Parker, Scott's Last Expedition, Natural History Museum, London, 2011, ISBN 9780565092870, A$25 |