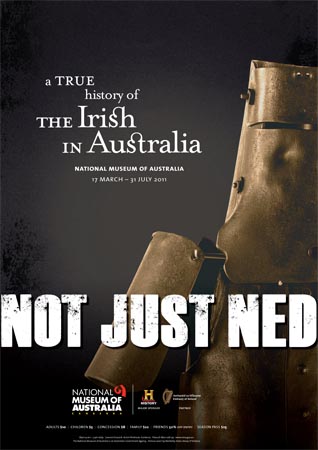

As viewed from the perspective of an Irish historian, the title of this exhibition encapsulates some of the contradictions inherent in it. Its aim is obviously to persuade the public that there's far more to the story of the Irish in Australia than just Ned Kelly. Yet the title refers to Kelly twice: first, familiarly, as 'Ned' and then again in its allusion to Peter Carey's 2001 Booker Prize-winning novel, True History of the Kelly Gang. Moreover, all the advertising for the exhibition features a photograph of Kelly's iconic helmet, while the four suits of Kelly armour occupy a prominent place at the centre of the exhibition. If the aim is actually to get away from the hackneyed outlaw and rebel associations of the Irish, why place such a relentless public emphasis on Ned Kelly? Perhaps the aims of the exhibition's curators have been compromised by the demands of its publicists.

Leaving aside the issue of the appropriateness of the publicity, does the exhibition really offer 'a true history of the Irish in Australia' that is 'not just Ned'? The answer to that question is both yes and no. Yes, in that there is certainly an extensive range of fascinating objects on display from a variety of private, state, national and international collections. The exhibition in terms of the sheer number and variety of its contents is unprecedented in Australia, and not likely to be repeated any time soon. Some of the objects are huge; some are tiny; many are little known and surprising. There is, for example, a quilt made by convict women during the voyage of the Rajah in 1841. Quilt making was apparently encouraged on convict ships in order to keep the potentially unruly women quiet, but this is the only complete, dated example known to have survived. There is a small wooden chest that in 1849 contained all the worldly possessions of a so-called 'Famine orphan': one of the thousands of Irish teenage girls shipped from overcrowded workhouses to the Australian colonies amid the horrors of the Great Famine. There is an enormous map of Victoria created in 1862, which plots in detail the land available for selection under Charles Gavan Duffy's land reform legislation; it is shown here publicly for the first time. The contributions of the Irish to agriculture, industry, commerce and engineering, which are not well known, receive considerable and commendable attention. Much better known in recent times is the phenomenon of the Irish backpacker — a transient young person visiting Australia on a working holiday — and therefore, perhaps appropriately, the exhibition concludes with a pack brought from Ireland in about 2000.

On the other hand, however, this is not so much 'a true history of the Irish in Australia' as it is an O'Farrellite history. Patrick O'Farrell's 1987 book The Irish in Australia is clearly the key academic text shaping the approach taken. It is discussed approvingly in the senior curator's introduction to the catalogue and, as a visitor enters the main exhibition space through a section devoted to St Patrick's Day, there is a quote from O'Farrell beside the door: 'Our selves are not only where we are, but where we have come from'. This sentence reflects O'Farrell's belief in cultural, and especially religious, determinism: his conviction that Irish Catholics shaped Australia far more than Australia shaped Irish Catholics; and that they shaped it in dynamic and positive ways, generating a constructive tension with the English that prevented Australia from emerging merely as a rather dreary antipodean version of England. O'Farrell was primarily a historian of Anglo-Irish politics and of the Catholic Church in Australia, and the exhibition reflects these preoccupations. He had little of substance to say, for instance, about the environment, women, Aboriginal people, social conditions, Protestants and literature — and the exhibition likewise doesn't treat most of these topics as fully or as imaginatively as one might have hoped.

There is instead a heavy emphasis on Catholicism, both in the catalogue and in the items selected for display, while politicians and male leaders also figure prominently. O'Farrell had highlighted the Irish quest for religious and political power, especially via the Catholic Church and the Australian Labor Party, and that quest is amply celebrated here. Of the 36 key objects singled out for discussion in the catalogue, nearly a quarter are religious and, indeed, the catalogue's cover features a picture of a garish, golden monstrance made in 1928 for Brisbane's Catholic cathedral. Cardinals, archbishops and bishops; church-, school- and hospital-building are treated extensively, as they are by O'Farrell. Governors, premiers, prime ministers and judges of Irish birth or descent are also to the fore. But controversial political events are more of a challenge to illustrate, and they are not always explained accurately — or even at all. Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne, for example, is given too much credit for the failure of the conscription referendums in 1916–17, while the Australian Labor Party split in the mid-1950s, which gave rise to the Democratic Labor Party, is ignored altogether, despite significant Irish-Australian Catholic involvement — including by Mannix again. The handling of the Eureka Stockade is particularly inadequate. It consists of a replay of scenes from a truly dreadful 1948 English-made film, scraps of the Eureka flag and a profile of Peter Lalor — played in the film by a hopelessly miscast Chips Rafferty — that attempts to minimise his later career as a harsh conservative. Other flawed 'Irish heroes', like WC Wentworth, Robert O'Hara Burke, Ned Ryan of Galong and Patrick Durack of Kings in Grass Castles fame, are also presented too uncritically. But perhaps this is partly due to the limited amount of text used: the captions on objects are often extremely brief and sometimes, due to poor lighting, they are almost unreadable.

The treatment of women is in the main depressingly old-fashioned. Of the catalogue's 36 key objects, at least 6 relate to women. We are presented with a 'Hellcat', a dancer, an actress, several nuns, a 'sweetheart' and, finally, the Australian winner of the 2006 Irish Rose of Tralee beauty contest. In this collection of traditional stereotypes, surprisingly, the most common Irish female stereotype of 19th-century Australia — 'Brigid', the incompetent domestic servant — is overlooked. The representation of Irish-Aboriginal relations is sketchy at best, but the catalogue correctly notes that this remains 'a largely unwritten story'. Why it is still 'unwritten', given the explosion of Indigenous-settler historiography in recent decades, isn't explained. Other 'unwritten' stories of the working-class Catholic Irish, as far as the exhibition is concerned, include as well their often desperate poverty; their frequent involvement in crime, whether as disorderly drunks or as gangsters; and their appalling health record, both physical and mental.

The paragraph devoted to Irish Protestants in the catalogue largely focuses on the Orange Order — reflecting O'Farrell's ambiguous attitude to Protestants and a tendency to associate them with bigotry. However, in the exhibition itself, Protestants are not presented so negatively or simplistically. Redmond Barry, for example, is celebrated more for his civic achievements than as the judge who sentenced Ned Kelly to death. And we are reminded that to the list of prime ministers well known for their Irish Catholic ancestry, such as Scullin, Lyons, Curtin and Chifley (strangely, Keating is omitted), we should add the Protestant Stanley Melbourne Bruce, usually seen as quintessentially English, but whose father was in fact born in County Leitrim.

| Exhibition: | Not Just Ned: A True History of the Irish in Australia |

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia |

| Curatorial team: | Richard Reid, Cinnamon Van Reyk, Rebecca Nason, Karolina Kilian |

| Designer: | Thylacine |

| Venue/dates: | National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 17 March – 31 July 2011 |

| Catalogue: | Not Just Ned: A True History of the Irish in Australia, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2011, RRP$A29.95 |