Museum Victoria is social media savvy, to put it mildly. Through its Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, Flickr galleries and exhibition blogs, it broadcasts 'behind-the-scenes' images, text and videos and invites questions and comment from virtual visitors everywhere. As a result, much of a new exhibition's content is made available before the physical space even opens. As I flew to Melbourne from Sydney on the day after the new Immigration Museum gallery Identity opened, I wondered whether I, who had been avidly following the exhibition development online over a number of months, had spoilt the surprise — like a child who sneaked a peak at their Christmas presents before they were wrapped. I couldn't have been more wrong.

Museum Victoria

Identity: Yours, Mine, Ours is not only a slickly packaged and well-promoted multimedia experience, it packs a punch in terms of exhibition design, layout, and that indescribable impact a good exhibition can have on the unsuspecting visitor. This is a significant achievement for Museum Victoria staff, considering the myriad obstacles and challenges that a theme such as 'identity' poses.

Entering the exhibition, visitors are met by strangers in Lynette Wallworth's video artwork 'Welcome'. Different familial and fraternal groups of all ages and appearances either welcome you warmly, or stand, arms crossed, with a look of disdain on their faces. In one scene, a posse of teenage girls turns their backs coldly and diverts their attention to their mobile phones. It is a jarring comment on the way we perceive others, and how social inclusion or exclusion can make us feel.

From this orientation we come to a large, fractured mirror, the surface of which reflects the visitor's gaze. It would be difficult to view Identity without confronting one's own prejudices, and this design is an effective, if obvious, feature evident in the exhibition's shiny, metallic surfaces.

So how do we define ourselves and others? Identity is divided conceptually into three broad sections: 'First impressions', 'People like us', and 'People like them'. The overarching theme of belonging centres the interpretation, and is the 'hook' of the exhibition's advertising campaign. Large banners with black and white photo portraits declaring 'I belong, do you?' hang outside the museum, and are replicated on bills posted on walls in unexpected places all over Melbourne. The Immigration Museum is clearly aiming at a youth market here, inviting traditional non-museum-goers into the space to see what is essentially a very non-museum-like exhibition. Rather than focusing on who we are as a nation, as museums have done in the past (especially around times of national celebration or commemoration), Identity forces us to look within — to consider how we constitute ourselves.

Museum Victoria

In 'First impressions', we encounter the objects and stories of many everyday Victorians. A large interactive audiovisual 'touch table' invites visitors to meet some of these people. Reminiscent of those first awkward questions at a dinner party or conference, we can find out about their job, their family, and their name ('my surname is always mispronounced and misspelt' complains one teenage boy). Other options open up deeper topics: touch 'who I really am' and we find out how these people see themselves. One woman defines herself by her adult children, and the eagerly anticipated birth of her first grandchild. A senior university lecturer defines himself as a proud gay Chinese-Australian, with a passion for comics and choir singing. In another vignette, the camera pans out to reveal a man standing in a room wrapped in a footy scarf, surrounded by pictures of his Aboriginal family, and then finally revealing his barrister's wig on a shelf nearby. Unlike some 'migration exhibitions', these personal stories all feel authentic, diverse and unscripted. Layers of identity are explored with thoughtfulness and humour, revealing that ethnicity and cultural heritage play an important part in some people's lives, but not others.

Museum Victoria

One irksome element to this innovative presentation was that a curatorial voice attempts to anticipate visitors' assumptions. It asks 'Where do you think I'm from?', 'Do you think my family has the same name?' or 'How many languages do you think I speak?' In my quest to find out who these people were, the pre-emptive questions seemed an unnecessary distraction, a heavy-handed way of emphasising the message that our first assumptions are not always accurate. That said, during my visit, many people lingered over the touch table, eager to find out about as many people as possible. Others grouped around displays of photos and personal objects. In 'What we wear', a curious jumble of jewellery is not linked to personal stories — the meaning is in the juxtapositioning of various cultures and generations. A bellybutton piercing, hip-hop pendant and Celtic cross necklace contrast with Greek worry beads, a Sikh bracelet and a simple gold wedding band dated 1908. Although some are marked as donations and others part of the collection, the more contemporary pieces are unexplained. I wonder who owned them, how they came to be in the museum, or whether the curators just popped into the local jewellery store to buy them. Perhaps it is not important, as their presence was enough to remind me that I too wear jewellery on a daily basis. I wouldn't feel 'me' without it.

More fascinating nooks and crannies abounded in the 'People like us' section. Some fabulous objects and stories had been sourced, including the footy hijab — an entrepreneurial creation of Melbourne fashion designer Shanaaz Copeland, who observed that her daughter and friends loved the sport, and wanted to show their allegiances at their school's Footy Day. Two young Aboriginal women tell their different life stories through art and poetry. For Bindi Cole, people's reactions to her fair skin were the catalyst for a series of photographic artworks in which she and her family pose in 'black face'. A hoodie designed by Western Victorian woman Kat Clarke during a project with the Koorie Heritage Trust is displayed along with one of her poems. Together they express her strength, pride and joy in life. Some familiar stories from the Immigration Museum's permanent exhibitions feature too. Anna Apinis's Latvian weaving patterns, which regular visitors will remember from the display of her loom for many years, and a wood carving by Czech migrant Eva Schubert; both tell stories of post-war migration. There are many other stories of people's discovery of, struggle with and celebration of their cultural heritage. Other topics such as disability, sexuality, and generation gaps are touched on rather than explored in depth.

Museum Victoria

phototgraph by Benjamin Healley

Museum Victoria

In 'People like us' the uncomfortable truths of prejudice are explored. Even before entering the area, you can hear the penetrating voice of Pauline Hanson declaring plaintively in her maiden speech to Parliament: 'I am fed up with being told, "This is our land". Well, where the hell do I go?' Other important speeches are available for visitors to view and respond to, and are grounded in a nearby timeline that depicts changing attitudes towards race from the sixteenth century until the present. This history of ideas, power and, ultimately, abuse of human rights is told as a global story. Within it, the history of race relations in Australia unfolds. As the only explicitly historical narrative in the exhibition, I felt that the timeline could have been granted more space. Lavishly illustrated by pictures, cartoons and small objects, the complex histories it told (of slavery, colonialism, and civil rights among others) felt overwhelming.

Museum Victoria has in the past excelled at interactivity in their exhibitions. The 2005 addition to the Immigration Museum's permanent galleries, Getting In, exemplifies this in the confronting interview room, where visitors must assume the role of Immigration Officer and assess prospective migrants. Identity continues this tradition, with a film set in a Melbourne tram. Called 'Who's Next Door?', the film dramatises an all-too common incident of prejudice — one of those moments where you think, 'Should I say something?' The powerlessness that we can feel when witnessing these moments of discrimination, bigotry or racism is so confronting that even presenting it in a fictionalised form, on screen, has an impact. The film, however, goes further, investigating the incident though the different inner monologues of the victim, the perpetrator, and two bystanders. I had already viewed the film on the exhibition's website. But standing in the space itself, which is designed to look like a tram interior, made the situation seem all the more real.

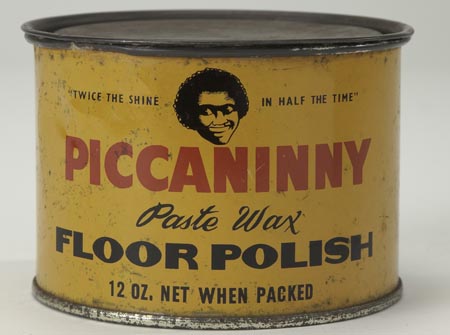

Australians adopted the paternalistic term 'piccaninny' from the United States to describe Aboriginal children.

Museum Victoria

The term 'wog' has shifted from a derogatory cultural insult to a badge of honour for many people of Greek and Italian background.

Museum Victoria

Identity is an exhibition with an agenda. For me, it harks back to the pioneering social history exhibits of the 1980s, which unashamedly had a political message to push. We are encouraged to discuss difference honestly with children, to publicly express our anger or frustration at discrimination, where appropriate, and to think twice before making judgements about people based on their appearance alone. By presenting these issues though the voices of regular Victorians, the curators have by-and-large avoided the preachy feel of a primary school lesson in diversity, or a training session on discrimination in the workplace. Instead, they step back, allowing their subjects to express their own feelings and frustrations. I was reminded of all those conversations I've had about tricky topics — conversations that usually take place informally, in situations where everyone feels safe. It's a tribute to all involved in Identity that they have brought those conversations to life in a museum.

Eureka Henrich is a PhD candidate in the School of History and Philosophy at the University of New South Wales. Her research examines how migration history has been exhibited in Australian museums.

| Exhibition: | Identity: Yours, Mine, Ours |

| Institution: | Museum Victoria |

| Lead curator: | Moya McFadzean |

| Exhibition/ graphic design: |

Andrew Scott-Young and Gina Batzakis, Gina Batzakis Design |

| Venue/dates: | Immigration Museum, 400 Flinders Street, Melbourne, permanent exhibition opened 9 May 2011 |