Remember me: The lost diggers of Vignacourt

review by Peter Williams

With the approach of the centenary of the First World War, the Australian War Memorial is returning to its roots. Conceived during the 1914–18 war, the Memorial opened in 1941, in the midst of another war. Expanding its remit with each new conflict, the Memorial has opened a new permanent exhibit on Australia’s current war in Afghanistan. But, for a while at least, during the centennial years 2014–18, the Memorial is refocusing on the Great War, where more than 60,000 Australian servicemen and women lost their lives. The First World War galleries are being redeveloped and there is a special Western Front exhibition, Remember Me: The Lost Diggers of Vignacourt.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial PAIU2012/115/39

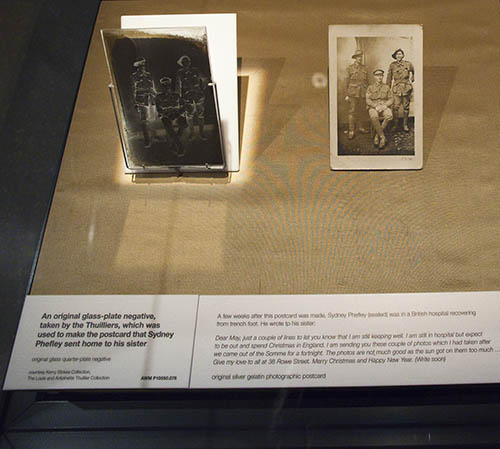

The small French village of Vignacourt, 15 kilometres north-west of Amiens, is the source of the exhibits. Always behind Allied lines, the village contained several casualty clearing stations and was a training and recreation area for troops of all nationalities moving to and from the battlefields on the Somme, 40 kilometres to the east. The Lost Diggers of Vignacourt tells the story of one photographer with an eye for an opportunity, Louis Thuillier. With his wife Antoinette, he opened a photography shop to take advantage of passing trade generated by the war. From 1915 to 1920, he took about 4000 images (that we know of). They show a side of the war less often seen: soldiers at sport, resting, caring for their horses, mixing with the locals and playing with children. More than 800 of these glass-plate negatives were donated to the Memorial by entrepreneur and philanthropist Kerry Stokes in August 2012. The exhibition showcases a selection of 74 of the photographs as handmade traditional prints produced in the Memorial’s darkrooms. The rest may be seen, and names searched for, in an interactive display and on the Memorial website.

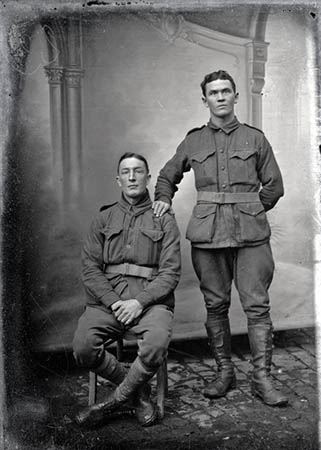

photograph by Louis Thuillier

Kerry Stokes Collection, the Louis and Antoinette Thuillier Collection, Australian War Memorial P10550.241

Captured by means of a light-sensitive emulsion of silver salts applied to a glass plate, printed on to postcards and posted home, the photographs made by Louis and Antoinette Thuillier enabled Australian soldiers to maintain a link with loved ones in Australia. The postcard was evidence that the man was alive and hale, at least when his image was captured. Some postcards survive, but for 85 years the photographer was unknown.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial PAIU2012/115/40

I went to The Lost Diggers of Vignacourt imagining it would be about Australian soldiers’ faces. I planned to stand close to the images and look into the diggers’ eyes to sense what I could of their war. I did that, and there are eyes aplenty. Stern ones, wistful ones, a cross-eyed pair, and ones that give nothing away. There are faces too, the handsome, the ugly, a grimace or two and some tipsy ones. Not just Australian faces, but service personnel from the polyglot alliance that fought on the western front: from India, France, the United States, China, Nepal and the British Isles. There are villagers, there are weddings and horses and dogs. There is little Robert Thuillier, son of Louis and Antoinette, perhaps four years old. Robert appears in more photographs than any other person, with a digger’s hand on his shoulder, or wearing a Red Cross armband while standing to attention next to a member of the Australian Field Ambulance. Robert’s smile suggests he enjoys the parade of strangers in his house.

photograph by Louis Thuillier

Kerry Stokes Collection, the Louis and Antoinette Thuillier Collection, Australian War Memorial P10550.134

The images don’t stand alone. The Memorial has drawn from its collection items to complement them. There is a lock of hair from William Charles Beresford Staley, who survived the war. There is Herbert Chudleigh’s concertina and Claude Jones’s brass euphonium. Beside an image of four diggers posed by Louis Thuillier before a simple backdrop cloth of an archway, is the cloth itself. It was found in Thuillier’s house not long ago.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial PAIU2012/115/10

The exhibition succeeds in its aim to tell the almost, but not quite, cheerful story of Vignacourt and its wartime visitors. Here and there are well-placed reminders of the other side of war: a pinch of soil from the grave of Reginald Hunter and images of rows of crosses of those who came to Vignacourt, but never left. They rest now in Vignacourt cemetery, just around the corner from Rue Thuillier. And many who did leave never returned. In July 1916, before the battle of Pozieres, the 1st Australian Division was billeted at Vignacourt. Charles Bean, the Australian official historian, described the division’s departure. ‘There was a perceptible sadness among the inhabitants, who of late had watched many similar units march away, to return a week or two later lacking a large proportion of the familiar jolly faces’.

photograph by Louis Thuillier

Kerry Stokes Collection, the Louis and Antoinette Thuillier Collection, Australian War Memorial P10550.640

Peter Williams is a Canberra historian who has written several books and websites on Australia’s 20th-century wars.

| Exhibition: | Remember Me: The Lost Diggers of Vignacourt |

| Institution: | Australian War Memorial |

| Curator: | Janda Gooding |

| Venue/dates: |

Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 2 November 2012 - 31 July 2013 |

| Website: | Remember Me |