Curating controversial topics: Developing an X-rated exhibition

From March to September 2015, Canberra Museum and Gallery (CMAG) presented the exhibition X-Rated: The Sex Industry in the ACT, which explored the social history of the sex industry in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). The exhibition wasn’t an attempt to gain publicity or even to shed light on an area of society that isn’t generally covered in museum exhibitions. Rather, the exhibition stemmed from CMAG’s commitment to explore stories of individuals, groups, places, sectors and institutions that have played an important role in the history of the Canberra region. The ACT is the only Australian jurisdiction where all aspects of the sex industry (sex work, the production and sale of pornography and the retail and live entertainment industries) are legal and regulated.[1] The industry is especially relevant to the ACT and, therefore, to CMAG’s audiences.

While it was almost certain that CMAG would focus an exhibition on this industry that has, for better or worse, shaped the history and popular perception of Canberra, it wasn’t inevitable. Exhibitions rely on objects and stories, and also on there being an institutional willingness to tell those stories. The sex industry was listed as a possible exhibition topic early in CMAG’s history, but the willingness wasn’t there to tackle the topic until recently. There were a few factors that made 2015 the right time for such an exhibition: key elements of the industry (such as the production and sale of pornographic videos and magazines) had peaked, allowing us to tell the story of the industry’s growth, peak and gradual decline, alongside the development of other industry components. Also, after years of speculative list-making, a compelling catalogue of material had been developed and was ready to be assessed for its potential to tell the key stories of the industry.

Determining the exhibition’s focus

Once the decision had been made to present an exhibition on the topic of Canberra’s sex industry, the question arose of how to do it. Exactly what would be covered in such an exhibition? What stories were able to be told? Which parts of the story were more or less relevant to the ACT? After extensive reading (and some navel-gazing), I made a curatorial decision that the exhibition would not seek to examine the broad national, international and societal questions that form the ethical and political arguments surrounding the sex industry. The question I would seek to answer, instead, was how and why the ACT came to be the only place in Australia with such extensive regulation and legalisation of the sex industry.

Negotiating legislation

This decision set the focus of the exhibition on the evolution of the three main aspects of the sex industry: pornography (including its production and distribution), sex work, and the industry bodies that are associated with those two sectors. A good summary of the content of the exhibition is provided in Frank Bongiorno’s exhibition review in the most recent edition of reCollections.[2]

In gathering stories and objects for display, I not only used CMAG’s collection, but also worked with Robbie Swan, a leading figure in the sex industry in the ACT and Australia since the late 1980s; members of the Sex Workers Outreach Project; and a number of individuals who have worked in or with the industry. I didn’t want the exhibition to promote the industry and, therefore, I didn’t approach contemporary business operators for input. The exhibition did include commissioned photographs of the exterior of current sex industry businesses and these were shown on a video display that included a set of quotes reflecting the diverse commentary that has surrounded the ACT sex industry.

As the exhibition developed, it became clear that there would be a number of explicit images on display and CMAG needed to consider how to manage this. If I didn’t include these images, the exhibition would have been presenting a sanitised vision of the industry. CMAG also needed to consider whether, in displaying the images, it would contravene relevant laws and, therefore, would require permissions or permits. In seeking advice from the ACT Government Solicitor, I foresaw that we might have to make the gallery a Restricted Publications Area under the Classification Act.3 What I didn’t anticipate was being told that there was material that we could not legally display without making specific arrangements in respect of the Act. As a result, some creative problem-solving was required.

photograph by Rob Little Digital Images

Under the Classification Acts (both Commonwealth and ACT), ‘to publish’ includes exhibiting and displaying material. Under section 36 of the Act, a ‘submittable publication’ cannot be left or displayed in a ‘public place’ if it is known that the publication is ‘submittable’. A ‘submittable publication’ is an unclassified publication that contains depictions or descriptions that are likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult to the extent that the publication should not be sold or displayed as an unrestricted publication, or are unsuitable for a minor to see or read.

CMAG acknowledged that the exhibition included unclassified submittable material and, therefore, it was illegal to display it. A number of options were available to us: we could decide not to display the explicit material, which would mean omitting some of the most interesting and relevant objects from the exhibition; we could take the risk that no one would complain and display them anyway (not the preferred option); or, we could apply to the Classification Board for the materials to be classified or for the exhibition to be exempted from the operation of the Act.

If the material on display had been works of art, no such issue would have arisen. An interesting double standard exists in the legislation governing the Classification Board’s decisions in that equally sexually explicit material may be dealt with differently by the Board depending on whether it is a bona fide artwork or not. This is because under the Publications Guidelines:

Bona fide artworks are not generally required to be submitted for classification as they are not generally considered to be ‘submittable publications’. Bona fide artworks which may offend some sections of the adult community may be classified in the ‘Unrestricted’ category when set in an historical or cultural context.[4]

Because, however, the material in this exhibition was social history, and documentary in nature, this clause would not apply.

After seeking advice from the Classification Board, it became clear that an exemption was not an option. Exemptions under the Act can only apply to films, festivals, or individual publications. For an exhibition, each item on display would need to be exempted as a separate publication. If we did apply for exemptions a decision would not be made in time for the exhibition to open. The only alternative, which was suggested in discussions with the Board, was to make the exhibition into book form and have it classified as a publication. The exhibition itself would, therefore, be equivalent to displaying the pages of a classified publication. We would also have the capacity to claim, if challenged, that we had done everything possible to ensure the exhibition followed the letter of the law.

Taking this path involved the expense of photographing each object in the exhibition and the time involved in collating text, object images and object labels into a publication. The Classification Board made their decision in three weeks and our ‘publication’ was given a classification of Category 1 – Restricted, subject to the condition that it be distributed in a sealed wrapper. The Board reasoned that:

the publication warrants legal restriction to adults and may offend some sections of the adult community. It contains realistic depictions of sexualised nudity containing genitalia and realistic depictions of actual sexual activity involving consenting adults.[5]

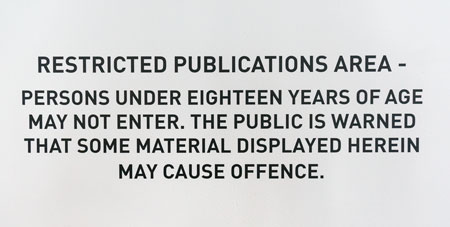

Managing the display

In anticipation of receiving this classification, CMAG had already decided to enclose the gallery space so that the exhibition would be presented in an area that was, in effect, a restricted publications area under the Classification Act, or equivalent to a ‘sealed wrapper’. Category 2 – Restricted Publications are required to be displayed in such an area, and although the CMAG publication received a lesser categorisation, such a measure would ensure that no one who did not want to, or should not, encounter the material would be able to see it accidentally. The gallery space in which the exhibition was displayed is located on an upper level of the gallery. Displaying the exhibition there meant visitors had to actively decide, after being informed of the content of the exhibition, to go upstairs to view it. The windows of the internal gallery space were obscured by blinds and the glass entry doors were frosted. Warning signs were placed at the bottom of the stairs and outside the lift, stating that only those over 18 years of age were permitted to enter the exhibition, and the following warning was placed outside the exhibition entrance:[6]

courtesy Canberra Museum and Gallery

Communicating with the public

CMAG was proactive in limiting access to the exhibition by engaging with the community of museum users who may have been affected by the exhibition content. The museum runs extremely popular education programs for preschool and lower primary age students that run throughout the year, as well as offering venue-hire opportunities to the community. It was decided to send letters to all schools and venue hirers booked in for the period of the exhibition, informing them of the measures taken to ensure that they would not be exposed to the material on display in this exhibition during their visit. There were no follow-up queries about this from the schools or hirers, and no complaints or withdrawals, just a few replies thanking us for letting principals and teachers know. While we might be accused of being over-cautious in this matter, we at least couldn’t be accused of not having given visitors sufficient information to make a decision about viewing the exhibition.

photograph by Rob Little Digital Images

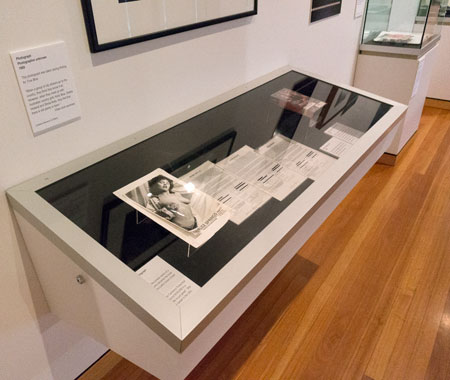

Another concern, which led us to seek the advice of the ACT Government Solicitor, was that of privacy. The exhibition included photographs of sex workers and dancers, as well as video slicks featuring actors in pornographic films that had been shot around Canberra. There were also images of participants on a ‘love bus’ tour of industry venues. We were advised that the majority of the items were ‘generally available publications’ and, therefore, privacy concerns were not an issue. This included photographs from the National Library of Australia’s collection that are available to the public online. Other photographs were taken with the consent of individuals and with the knowledge that they were for publication or distribution. We redacted information from three documents (model release forms) so that the actors’ real names and addresses would not be visible.

photograph by Rob Little Digital Images

Briefing the board of CMAG and relevant ACT Government agencies and offices on the exhibition’s contents was another important measure to ensure the smooth running of the show. Briefing was provided to the Chief Minister, other ministers and their advisers, and a briefing session was offered to the opposition. Three members of the opposition in the Legislative Assembly previewed the exhibition with the CEO of the Cultural Facilities Corporation (of which CMAG is a part), the director of CMAG and the curator.

It is our belief that this combination of measures pre-empted a range of potential issues. Preparation for the briefings led us to consider in greater detail the many issues and questions that might arise from the exhibition and this helped us to clarify what we aimed to achieve and why we had taken certain curatorial decisions. In addition, we ensured that the exhibition’s content did not come as a surprise to anyone who might misrepresent our ambitions as a result. Potential audiences were warned as to what the exhibition contained and why the content was there. Even if they didn’t agree with it, we had answers ready that dealt with the key concerns.

In the same vein, we sought media opportunities before the exhibition opened to the public. This avenue of communication framed the early reception of the exhibition by the public and clearly enunciated CMAG’s aspirations for the exhibition. CMAG invited the local Australian Broadcasting Corporation radio station to conduct an outside broadcast from the exhibition and suggested possible subjects for interview, including the curator, to ensure that the intent (and content) of the exhibition was accurately represented. We also invited major media to preview the exhibition and conduct interviews. The result was a saturation of local media during the week in which the exhibition opened, but no immediate negative responses.

The public response

Generally, the exhibition received positive responses. Alongside the many positive statements in the Museum’s comments book that were directly related to the exhibition, two comments were negative. One visitor called for more input from sex workers, while the other disagreed with the topic being covered at all. The positive comments praised the exhibition for being brave, insightful and intriguing.

Two letters were received by CMAG that praised the exhibition and the museum for presenting it, while the mainstream media response was also positive. We also received informal feedback from sex workers indicating that they enjoyed the exhibition. One visitor commented via social media that the exhibition was heteronormative and failed to represent the history of homosexual sex workers.

The main criticism of the exhibition was posted on a website. Two pieces were published: one by an ex-sex worker and one by an anti-sex work campaigner and academic from Victoria. Both pieces criticised the exhibition for glamorising the industry and failing to present the damage that the industry can do to workers.

I had anticipated more negative responses than were received and was gratified that this didn’t eventuate. The exhibition had good exposure and good visitor numbers, so clearly the public knew that the exhibition was occurring. I am thankful that the public generally understood the purpose of the exhibition and agreed that it is CMAG’s role to present an exhibition of this type.

Lessons learned

It is also important to consider what could have been done better. The issue of representing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) sex workers was a concern to me. The ‘industry’ side of sex work (i.e. brothels, massage parlours and locally produced commercial pornography) in the ACT has largely been focused on women providing sexual services to men, including two women working together with a male customer and women working with heterosexual couples. As one visitor pointed out, there would certainly have been, and are, LGBTI workers in the ACT industry, but the record reveals this as only a small percentage of the industry. Reflections from a male sex worker were included in the video display, and the statistics referred to in the exhibition recognised male workers. However, there were no stories specifically about LGBTI workers. CMAG could have sought out some contemporary stories, perhaps more easily uncovered than those from the past.

While we recognised that the exhibition presented a unique opportunity for CMAG to host a public forum to explore and debate the ethical issues that are relevant to the sex industry, on consideration, it was decided that the audience for such an event would have been limited and the potential for volatile encounters between pro- and anti-sex industry activists and pornography campaigners would have distracted from the historical focus of the exhibition. Such a forum might, however, have encouraged those anti-industry campaigners who criticised the exhibition from a distance, revealingly misrepresenting what was on display, to engage in a more productive debate within the museum.

While this exhibition may never be repeated, it is hoped that our experience in putting it together will be helpful to other museums that find themselves presenting controversial content, especially sexually explicit content. CMAG’s experience should encourage other museums to tackle controversial issues – the museum-going public might just be more receptive to the exploration of such issues than we give them credit for.

Endnotes

1 The sale of X-rated films is also legal in the Northern Territory (NT), however, since 2007 the possession of pornography has been banned in many NT Aboriginal communities.

2 Frank Bongiorno, ‘X-rated: The sex industry in the ACT’, exhibition review, reCollections, vol. 10, no. 2, 2015, http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/volume_10_number_2/exhibition_reviews/x-rated2.

3 Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) (Enforcement) Act 1995 (ACT).

4 Guidelines for the Classification of Publications 2005 (Cth).

5 Classification Board, Classification Certificate for a Publication, Classification no. 265236.

6 This wording is prescribed in the Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) (Enforcement) Regulation 1995 (ACT).