« back

::

next »

Exhibition as edition: Edition as exhibition

An exhibition of Van Gogh's letters at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

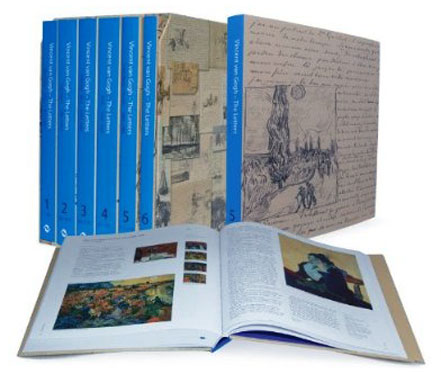

Coinciding with the publication of a splendid, fully illustrated six-volume edition of Vincent van Gogh's 800-odd letters there was a temporary rehang of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. I had received a notice of an exhibition at the museum relating to the edition and expected to see a small section of the gallery devoted to it. About 10 years ago, because of my editorial connections, I was privileged to be taken down into the vault of the gallery's library to see the Van Gogh letters, of which the gallery owns about 90 per cent of those still extant. Dick van Vliet, at that time director of the Huygens (scholarly editorial) Institute of the Dutch Academy of Letters, took me to see one of the editors, Leo Jansen, there. The work had started in 1994, and soon I began hearing papers by Jansen or his fellow editor Hans Luijten at editorial conferences in the United States and in Europe about the project. I had not fully appreciated until my visit how very substantial it was.

One advantage that this new edition lacks, however, is sturdy binding. Only two layers of paper link the hard covers to the spine, and already the bindings of copies of these 2009 large-format books at the museum available to visitors are coming loose, or torn at the hinge, through rough treatment. The covers are of course fully illustrated, in keeping with recent practice. The edition has been published simultaneously in three languages, the three that Van Gogh himself used for writing the letters: Dutch (the great majority); next, French; and last, English (six letters in total, including two letters to the Australian artist John Peter Russell and one written by him). The six-volume set in each language costs 395 Euros, boxed (the box is also illustrated). If you buy, handle carefully.

But once you are safely inside, all is well: the edition is a triumph. I cannot speak for the adequacy of the translations from the Dutch and French. But the explanation (in Volume 6) of the editorial approach to the translation of private correspondence never meant for publication shows all the sensitivity, care and good sense that one might expect from fully informed, modern-day scholarly editing — in which the Dutch, courtesy of the Huygens Institute and their universities, have been a shining light in Europe. This is a small country that knows how important is its written and printed heritage, and that is fully aware of its own very long publishing tradition in Latin and secular languages. Take for instance the Complete Works of Erasmus (in Latin). An international project of nearly 50 years standing and organised from and published in Holland, it has recently reached Volume 75. Every fully annotated volume of the work of this great humanist is a major editorial achievement.

We in Australia — despite our larger population — do not even begin to compare with this enlightened attitude by putting sufficient public funding behind such noble editorial endeavours. And if not from public funding, then from what source? Without subsidy, our publishers seem too cash-strapped or timid to take the big risks. We do things on the cheap, mostly, and it shows. Our philanthropists support mainly fashionable forms of scientific research, the opera, ballet, and the state and national art galleries: but that's about it. It's as if our written and printed cultural heritage did not exist or does not matter. Where is the large-scale long-term commitment? Which well-connected person will organise the search for philanthropy that would be required?

Back now to the truly heartening story. The Van Gogh Museum approached the Huygens Institute when Van Vliet was director. No one at the time knew how extensive the resultant collaboration would grow to be. But everyone involved held their nerve as the project grew and grew. As a result, there have been no shortcuts. The editors, the two institutions and the co-ordinating publisher, Mercator fonds in Belgium, are to be congratulated.

But how did the editorial work affect the special-exhibition hang? Here's how it felt when one entered the Van Gogh Museum during the three-month exhibition period in late 2009. Because I recorded my impressions immediately after the visit, with the excitement of it fresh upon me, I use the present tense to try to share a sense of being there.

Having negotiated the usual impedimenta and arrived properly inside the building, the ground floor introduces you to the idea that the letters and the paintings are interlinked. You wonder at first in what sense this can be so. The wall text is biographical — no surprise there. The artist was in reaction against the cities and found a Romantic solace in the country; but his paintings didn't sell. So he moved to Antwerp and then to Paris, where his younger brother Theo was living.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

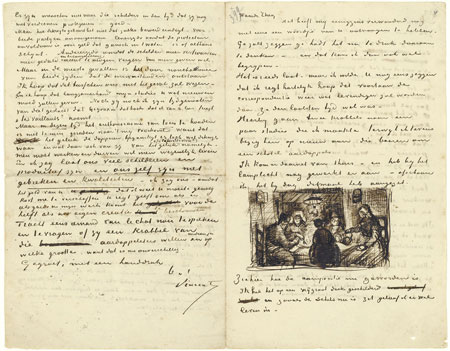

What gradually emerges is a sense that this romantic madman-artist of legend was a highly self-conscious thinker who sought carefully to advance his art through discussion. He needed a context for his lone practice, and his correspondence helped create one. There was a practical side too. Theo sent the paints Van Gogh requested for the painting that he was now, in the letter, sketching.

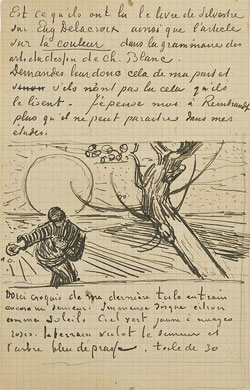

In another vitrine is a thick volume by Charles Blanc, Grammaire des arts du dessin (1867) on painting methods and on colour: Van Gogh studied this treatise with great attention. Next to it is a lacquer box full of balls or buns of wool: two colours woven together by hand so that Van Gogh could survey their effect on one another, evidently trialling what he might do in a painting. This display helps you to understand the technique of his paintings with their vivid (or subdued) contrasting colours side by side, applied confidently, often in long strokes. Suddenly the ink drawings in the letters make more sense: his rapid ink-strokes a couple of centimetres long give a pointer to the technique of many of the paintings. But it would be a mistake to characterise all Van Gogh's paintings in this way, for his technique was constantly changing. And that's because he was actively engaged in thinking about it and discussing it. This was not Poor Vincent: now, we begin to triangulate back to the artist at work.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The next floor is more entirely given over to letters, some nicely squeezed between two layers of glass at eye height so that both sides can be read, as if the text is transparent (thus literalising the traditional metaphor of print-as-vehicle). Several metres of book-case-style vitrines contain several hundred volumes of previous editions and translations of Van Gogh's letters, those predecessors of the new edition; and computer screens give you access to the online version of the edition. This contains facsimile images of all the letters (not only those with illustrations, as in the book). You can find the electronic edition at www.vangoghletters.org but the book is easier to use and reassuringly familiar. You know at a glance where you are up to and what remains: a welcome feeling. The online edition is doing what it ought: it is acting as an indispensable supplement to the books, providing what, even with six volumes, they could not economically do. As a result the online edition is not interactive, but this is not a problem if your point of orientation is the book. Some of the illustrations in the letters give images of paintings that have not survived or were never finished or destroyed: so that they are testimony to proto-works or former works.

The curators have realised the idea of the exhibition as edition, of the edition as exhibition. The convergence is remarkable. Editorial theory has been absorbed with distinction into a rationale for a whole-of-museum exhibition. Van Gogh emerges as both legend and deliberate craftsman, as calculating self-conscious technician, as intellectual of his own practice and as commentator on the art scene of his time. The edition has images of every artwork he comments on. There are hundreds. Quite a few are on the walls of the museum. The intertextual weave of his imaginative striving is helpfully staged for us.

His adaptation of the paintings of Rembrandt, Millet and Delacroix while in the asylum (after his insanity showed itself in 1888) take their composition from the black-and-white prints that Theo had sent him. But Van Gogh coloured and forcefully enlivened them according to his distinctive talents and directions. Maybe the activity of painting them was a creative pause, a taking stock, half being someone else, before relaunching his last furious few years of independent creative work. They are like collaborations, except he has made them entirely and idiosyncratically his own. These brilliantly original copies are Van Gogh's: no doubt about it.

| Institution: | Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam |

| Exhibition: | Van Gogh's letters: The Artist Speaks |

| Curatorial Team: | Nienke Bakker, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten |

| Exhibition space: | over 4000 square metres |

|

Venue/dates: | 9 October 2009 – 3 January 2010 |

« back

::

next »