« back

::

next »

At the National Portrait Gallery: Art or history?

by John Thompson

It is now almost a year since Australia's National Portrait Gallery (NPG) opened in its new and permanent home, an $87m building designed by the Sydney firm of Johnson Pilton Walker and the recently announced winner of the 2009 Australian Institute of Architects Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture. But while the gallery is the youngest of the national collecting institutions and its building the most recent addition to the cluster of cultural edifices that sits along the shoreline of Lake Burley Griffin, it is no mere arriviste though it is still very much in the making.

In just 10 years the NPG, working with an enthusiastic and committed professional staff that has grown with the institution, has developed several major exhibitions, a strong public events program including a prestigious annual lecture and an outstanding education program. It has also embarked on the process of building a permanent collection, securing several major acquisitions including John Webber's Portrait of Captain James Cook, RN, painted in 1782; and it is harvesting the returns from a commissioning program designed to construct a representation of contemporary Australian portraiture that matches skilled artists with distinguished subjects in major fields of endeavour. As its honour boards and many of its wall captions attest, it has also nurtured an impressive network of donors and benefactors. The most significant of these, led of course by the Darlings, are honoured in the naming of the building's gallery and public spaces. With its specialist focus and its nurturing patrons, the NPG has become something of a pacesetter in the community of Australian cultural institutions. It has quickly overturned doubts that existed in some quarters about its viability or appeal and is in many ways a splendid realisation of the Darlings' vision.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the idea of an Australian portrait gallery did not come easily or quickly. In the early years of Federation the nationalist painter Tom Roberts had advocated the building of an Australian collection of portraits, looking to the model provided by Britain's National Portrait Gallery, but his suggestion attracted little interest or support. It was not until the late 1980s, in the euphoria of celebrations that marked the bicentennial of European settlement, that Gordon and Marilyn Darling began their earnest and, as it proved, highly strategic advocacy for the creation of a dedicated Australian institution that might commemorate the country's notable men and women. Their vehicle for promoting the cause was the exhibition Uncommon Australians: Towards a National Portrait Gallery, which presented 116 portraits in a range of media (all borrowed from institutional and private lenders) and which was shown in Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane, Sydney and Adelaide from May 1992 to January 1993. One of the stated aims of this promotional exhibition was to match 'some excellent portraiture with achievement of consequence' and thus to make the case for an Australian National Portrait Galley that 'would bring Australian history to life' while showing 'some of the strongest and best known art the country has created'. In offering this statement of their vision, the Darlings emphasised that the portraits selected for Uncommon Australians were not to be understood as either comprehensive or as a definitive roll-call of greatness or endeavour but as 'a sample only to whet the appetite and to suggest the scope and variety that an Australian Portrait Gallery would encompass'.[1]

Now that the NPG has opened in its permanent home and its officially designated 'Inaugural Hang' has been in place (with some changes and adjustments along the way) for a year, it is timely to cast a reflective eye over the activity that is its principal undertaking: the presentation of what it calls the historical display of portraits of subjects who have made an impact on Australia. As a going concern, it is time also to look at just what the NPG actually encompasses, even if it remains at present in the early stages of its development with much consolidation still before it. Exactly what sort of meal has been presented to feed the national appetite for portraits that was so shrewdly appraised by Gordon Darling in 1992 and which Sydneysiders especially celebrate each summer as they flock to the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the circus of the Archibald Prize?

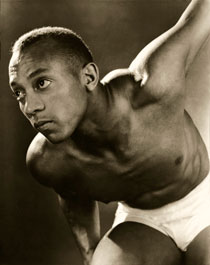

photograph by Lusha Nelson

© Conde Nast Archive, Conde Nast Publications Inc.

As a cultural enterprise seeking to make its way as a new institution in Australia, there has been nothing quite like the Darlings' remarkably well-coordinated approach both to advocacy and to concrete planning. But it probably helped, that in what will now be called the foundation years, the aspirational young NPG had the ear of the Howard government. As the 'history wars' raged on, we may guess that the NPG, properly supported with resources and a home of its own, offered a most attractive option for the realisation of the then prime minister's preferred narrative celebration of high Australian achievement. And we may guess also that in his successor Kevin Rudd — socially conservative in ways not unlike John Howard though of a different political persuasion — the NPG will find similar strong support and approval. Before the Howard ascendancy, Paul Keating as prime minister had not been a natural supporter: he had come somewhat grudgingly to the view that a gallery of Australian portraits was 'one more gallery worth having'. But he too came to like the idea that such a gallery might 'excite a wider interest in our history and society' and that 'it might encourage us to learn the story of Australia and to better understand the stories of our fellow Australians'. In a Keatingesque luck's-a-fortune kind of way, he thought those stories might show Australians that 'life is what we make of it',[6] a vision perhaps a little different from the more reverential 'great and the good' approach that some suspected was implicit in the original Darling vision of an Australian gallery of portraits.

Beneficial as they have been, in time these supportive relationships might bear some closer examination as critics and observers come to analyse the networks of connection and influence in the visual arts in Australia and to assess the power of philanthropic support in determining certain outcomes or in giving particular shape and form to institutions such as the NPG. There are some who might see that the NPG functions too much as an art gallery and rather less as a social history museum though by definition it is clearly a mix of the two. While Australian art galleries and curators owe a great debt to the Gordon Darling Foundation (and to other arts-related benefactions also generously funded by Gordon Darling), it might be asked whether this has not hijacked the NPG to function first as a popular art gallery and only at a remove as a museum of social history. More generally, it seems that good manners may have exempted the NPG from a more rigorous and critical scrutiny not only of its role and function but also of its independence as an asset of the Australian people — not more narrowly the possession or sphere of influence of either its first promoters and supporters (however generous they have been) or of that sector of the community of museums that is affiliated specifically with the visual arts.

It is the uncertain and uneven nexus between the NPG's two rather different but related roles of art and history that seems so far to have eluded a wider critical discussion in the successful realisation of the Darlings' dream to bring the gallery into existence as a national institution. As noted, only Humphrey McQueen — always a fiercely independent and courageous critic — has run against the tide of congratulatory acclaim to pose those questions about role and function. In 1992 McQueen was a conspicuous critic of the Uncommon Australians exhibition, which he said combined 'bad history and inadequate psychology with inferior art'.[8] Turning his attention to the permanent NPG located now in its own custom-made building, McQueen asserts that nothing has improved. In his view, the NPG has ended up with neither the narrative dreamed of by John Howard nor the cultural studies treatment traduced by his lackeys.[9]

McQueen backs his characteristically blunt generalisations with a number of detailed criticisms. He notes the lack of any guidance to visitors in understanding the relationships between the historical subjects represented (especially in the two early colonial galleries) or of any timeline of governors to help visitors whose grasp of Australia's historical chronology can these days only be approximate at best: governors and explorers, once the staple of school history learning in Australia, are now almost entirely unknown. McQueen also takes aim at the selection itself: both its inclusions and its exclusions. He notes especially a bias towards broadly 'establishment' figures and is critical too of what he sees to be the indifferent quality of many of the portraits on show. Where there are portraits of obviously better quality — such as in several fine though too numerous self-portraits by Australian painters — McQueen ponders the imbalance this suggests. Writing of the overall selection he notes that 'the portraits are so demographically askew that a Martian would report that nearly half the Australian population has been employed in the arts'. He is stern too in his observation that in what seems to be overall little more than a random or eclectic selection of historical subjects throughout the various gallery spaces, the NPG is really only shuffling its collection (both actual and borrowed). He chides that 'being given a package of 500 stamps of the world does not make a child a philatelist'.[10]

One must guess that McQueen's harsh words will have rankled with the NPG as it has otherwise basked in the twin suns of official regard and the acclaim of the visiting public. But churlish and argumentative as they are (and not always sensitive to the impediments that exist in the building of a new and specialist institution), there is the danger that those words may too easily be brushed aside as an aberration rather than as a contribution to a critical and constructive debate about how the NPG goes about the business of telling the national story. It would be unfortunate if this was so, since there is merit in McQueen's complaints. Critic though he is, he too wants to get it right or at least to see a job better done than is the case at present. While at heart he might disdain the idea of a portrait gallery as being inevitably elitist and predictably celebratory, in fact McQueen goes on to offer up a number of stimulating ideas for ways in which the NPG might proceed. Specifically he proposes the mounting of a number of themed exhibitions that might look critically and thoughtfully at particular aspects of portraiture in the Australian tradition that would enable conclusions to be drawn about more focused areas of Australian achievement. This would also provide some more coherent treatment of the evolution and traditions of Australian portraiture itself, a medium of wide variations in quality and with excellence (though certainly not interest or historical importance) a limited commodity.[11] Crucially, McQueen suggests that an important and necessary beginning, and one strangely absent when the building opened its doors at the end of 2008, might be for the NPG to construct a clear statement of intent — an indication of how it means to proceed.[12] So far that remains unclear.

It is surprising indeed that the NPG has so far seen fit to state its purpose only in the most general and obvious of terms. As McQueen suggests, a clear statement of a prevailing vision is not offered in the galleries themselves and it is not present in the otherwise attractive and highly readable published booklet, The Companion, issued to coincide with the opening of the building in 2008. Nor does such a statement exist, other than partially or by implication, in the NPG's own policy documents. Its Charter of Operations 2008/09 states simply that the purpose of the NPG is to 'increase the understanding of the Australian people — their identity, history, creativity and culture — through portraiture'; and in the guidelines for the development of the permanent collection we are told that the responsibility is to create a collection 'of the highest quality, and of subjects who have made an impact on Australia'.[13] Superficially persuasive, these statements beg the question that it is always possible to align the quality of a portrait with the historical importance of its subject. If this test was seriously applied to much Australian colonial and twentieth-century portraiture, the NPG would surely struggle to do its job. It is surprising too to see the subjects of portraits apparently considered to be of secondary interest to those who painted them.

In this context it is instructive to compare the ambitions of the Canberra stripling to the stated purpose of Britain's National Portrait Gallery, probably the leading exemplar in the field and the one best known to Australian travellers. There the purpose is to acquire portraits in all media of the most eminent persons in British history from the earliest times to the present day. In meeting this objective, the present-day trustees continue to honour the precept of their forebears (declared in 1857 at only their second meeting) that while looking to the celebrity of the person represented, the attempt is made 'to estimate that celebrity without any bias to any political or religious party'. In that consideration, great faults and errors, even though admitted on all sides, will not be considered as giving any sufficient ground for excluding any portrait which may be valuable 'as illustrating the civil, ecclesiastical, or literary history of the country'. Here, by comparison, is a more precise, determined and inclusive statement of purpose: it is one that places its primary emphasis firmly on the historical subject. While quality is important, it is not pursued as an end in itself. Rather the trustees 'have regard to the importance of the image [and] the significance of the artist'.[14]

It is striking that in the various justifications proposed for a national portrait gallery in Australia, the common theme is that it might tell an Australian story or, in Paul Keating's more inclusive language, 'the stories of our fellow Australians', since clearly he understood that there can be no single prevailing narrative. But how first to conceive that story (or those multiple, diverse and sometimes contradictory stories) and then how to find the ways to represent it or them by the particular means of portrait representations of those who were participants — whether as achievers, rebels, renegades or victims or, more simply and democratically, as representative Australians? While there are certain conceptual and philosophical issues to be debated here, it is surely not enough, as in the present NPG hang, simply to place portraits on the wall, to provide some brief biographical details in captions and to imagine that a story has been told. It is true that throughout the galleries there are specific groupings of loosely related portraits and that certain broad themes are sketched in the introductory wall captions provided for each defined room or section. There are five of these sections that pursue a loose chronological progression and offer a diverse though not always balanced or rounded selection of subjects from the late eighteenth century to the present. An additional gallery offers an eclectic selection of contemporary portraiture. But the major wall texts are couched in such vague and general terms that it is possible only to draw out what seems at best to be an illustrated Australian version of the good old-fashioned Whig narrative of history, an illustration of inevitable progression to good and better things. And in the hang itself, where there are connections between subjects beyond merely temporal ones (unless they are marriage partnerships or family groups), these are tenuous at best. Australia's Federation story for example, rich though it is in portraiture and also nicely self-contained, is only partially and unevenly represented — perhaps it can be explored in greater depth in the future. In the current NPG arrangement, history seems to be the loser, with portrait selections set within the loosest and occasionally the most anodyne of historical frames.

For what is arguably the most crucial of rooms, that for portraiture from the late eighteenth century to the 1830s when Australia becomes an invaded space, the introductory caption (like the others that follow) is cast in the broadest of generalities. Here, a large and contentious story is reduced to a few familiar lines about a territory occupied by a mix of Indigenous people, explorers, navigators, the first wave of European settlers and colonial administrators. Then follows the merest hint of the clash of cultures and of dispossession: we are told that those who arrived encountered an Indigenous population 'with a complex and ancient culture', while the settlers themselves 'brought with them expectations of exploration and acquisition, attitudes of moral and religious duty, and European systems of science and classification'. Finally we are instructed that portraits of this period 'ranged from formal oil paintings to miniatures, each with their own claims to status and intimacy', while a tradition of printmaking meant 'that portraits were accessible to many, serving the purpose of providing information for viewers in Britain and Europe'.

Is this really enough? And is it good enough, when we know that the most current writing about Australia's European beginnings is confronting a more brutal and morally challenging reality? While her important new book The Colony postdates the opening of the new NPG building, Grace Karskens alerts her readers to a potent truth: for her, 'the year 1788 is the fatal turning point, where black "prehistory" is neatly sheared off so that the white "history" of city-making can begin'.[15] Of course, wall captions can only be summaries of major themes and ideas, but in charting the course of the nation's complex past as a guide to the enlightenment and understanding of visitors (not only local ones but those who come from other countries), it is reasonable to expect the NPG to acknowledge the ambiguities and complexities integral to Australia's settlement narrative and then to better place the first colonial portraiture into its temporal and historical context.

Again using the NPG's first chronological aggregation of Australian colonial portraits as the example of its larger approach to the business of national storytelling, it is important to offer some remarks on the selection of subjects and on the aesthetics of the presentation. The room (Gallery 3), it must be said, is extremely attractive both in scale and in its arrangement of images. In this it is immediately reminiscent of the small and intimate rooms that are part of the National Gallery of Australia's permanent hang of its Australian colonial paintings. But in art gallery mode, this pervasive charm of presentation seems to prevail as an end in itself. Since the subjects vary so greatly in relative interest and importance and in their connections with each other, they end up telling no story of any meaningful historical coherence — and this at a time when Australia's European foundation has been examined and interrogated in fresh and interesting ways by historians such as Alan Atkinson and Inga Clendinnen (and these followed more recently by Grace Karskens and the novelist-historian Thomas Keneally) and also by the limpid storytelling of a fiction writer such as Kate Grenville. These and other writers have provided a lively renewal of interest in the personalities present in foundation years of European settlement.

Even without these more recent accounts, a return to the first two volumes of Manning Clark's ambitious narrative A History of Australia (1962; 1968) would have suggested groupings and possibilities that, if they could have been brought together, would have delivered a greater consistency and coherence to a selection that, in the NPG hang, seems little more than random or opportunistic and which sometimes is merely pretty. While Clark himself — working within his publisher's limits — is not systematic, he does offer representations of some of the major personalities, including the five foundation governors from Arthur Phillip to Lachlan Macquarie. He also gives us David Collins, the first deputy judge-advocate who, with Watkin Tench and others such as Surgeon-General John White, was one of the notable chroniclers of the foundation settlement. Brought together, those who told the foundation story might have provided an especially informative grouping of faces and one made more interesting in the aftermath of Inga Clendinnen's widely read first contact history Dancing with Strangers (2003) that uses those accounts to explore the fateful meeting between the new European arrivals and the local inhabitants. Manning Clark's selection also gives us the clerics Richard Johnson and Samuel Marsden, both in different ways influential foundation figures, and also Ellis Bent and Jeffrey Hart Bent, the two difficult lawyer brothers of the Macquarie era, who helped consolidate the establishment of British law in Australia.

These absences and the suggestions made to fill them, however, draw attention to a crucial difficulty faced by the NPG: many of the most important Australian historical portraits — some of them not significant as works of art but nevertheless the defining images of their subjects — belong to other institutional collections. Coming late to the business of building a collection of its own, there are certain likenesses that cannot now be acquired. If they are to be seen in Canberra at all, they must be borrowed (as indeed is the case already with most of the works in the present hang). Clearly this requires the full, generous and continuing cooperation of lenders, particularly of kindred institutions such as the State Library of New South Wales and the National Library of Australia, which have built rich holdings not only of early Australian portraits but also of other documentary and topographical art in various media that might also be relevant. As the list of current lenders shows, various owners, including the big institutional libraries, have been forthcoming in their support of the NPG but with their lending not always made to the greatest effect. Presumably this reflects either what is asked for in the first place or what a lender, particularly institutional lenders with agendas and obligations of their own, is willing to make available and for how long.

by Joshua Reynolds

While this is especially the case with the foundation period, where images of most of the major personalities can be assembled to tell an integrated (even complete?) story of relationships and connections, of the struggle for power and its loss and of the establishment of institutions, it is true also of the later periods. The NPG deals with these in the same partial and seemingly random or arbitrary and opportunistic ways. Borrowing selectively because a portrait looks good or has a beautiful frame or on its own tells a single interesting story is an odd way to proceed. Now that the NPG is secure in its own home, it must come to terms with a more complex brief than the ones it has worked with in its several pioneering incarnations when it could more easily get away with sampling or with indicative representations of notable subjects. In Australia it is conspicuously the case that borrowed 'blockbusters' have served the big art galleries and their public well over many years: they have educated taste and enlarged awareness and understanding of individual artists or of noted historical periods and movements. In its specialised field of portraiture, working with an eye first to history and then to art, the NPG must aim to bring a greater range, texture, consistency and connectedness to its telling of Australia's story or stories. In some cases, such as the foundation years of European settlement where rich possibilities exist, the burden of lending will fall more heavily on some institutions than others (the State Library of New South Wales stands out), but as a way forward this must be negotiated and encouraged if the NPG is to be supported in doing its best work.

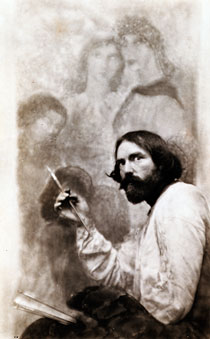

photograph by Malcolm Arbuthnot

© Conde Nast Publications Inc

oil on wood panel, 53.4 x 64.7 cm

by Rupert Bunny

oil on canvas, 46 x 38.5 cm

oil on canvas, 77 x 63.3 cm

Recently, the scholar Nathan Garvey (who has unravelled much of the long historical speculation and confusion that surrounds the life of the intriguing, contentious and problematic George Barrington) has introduced a note of caution on both the attribution to Beechey and the identity of the subject. In Garvey's admittedly speculative observations, the suggestion is made that the sitter might not be the rogue Barrington but rather the Reverend George Barrington (1761–1829), later the 5th Viscount Barrington, who had no known connection with Australia.[18] It is true that the National Library of Australia, which owns the portrait, has itself never called into question the claims originally made for it by Rex Nan Kivell (whose personal record of biographical reinvention is well-known and whose inclination to gild his historical lilies was not always above reproach). However, it is important now that we should be able to look to the NPG as the commanding Australian authority in matters of portrait scholarship, which has been a poorly researched field of art historical investigation in this country. With NPG leadership, it will be interesting to see over time a needed revision of some of the myths and claims that have evolved in the history of Australian and Australia-related portraiture.

In published remarks he made when the new building opened in December 2008, Andrew Sayers stated his view that the gallery's aim is the achievement of what he calls 'national understanding' or 'national knowledge'.[19] Superficially these bites might occasion a nod of the head, but what do they really mean when they are tested against the long clothesline of faces strung out in the NPG's galleries in Canberra? Certainly there will be for many an absorbing interest in the array of faces and in the varieties of experience — colonial and national — that we see assembled together in the first major statement by the NPG in its new home. But the show meanders with a bit of this and a bit of that with only occasional groupings that serve to tell a more coherent story. Towards the end it trails off inconclusively with an odd and idiosyncratic selection of more recent Australians that is less about achievement than celebrity.

by Hugh Ramsay (1877–1906), oil on canvas

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

1 Gordon & Marilyn Darling, 'Foreword', in Julian Faigan (ed.), Uncommon Australians: Towards an Australian Portrait Gallery, Art Exhibitions Australia Limited, Sydney, 1992, p. 8.

2 The Australian, 3 October – 1 November 2009, p. 3.

3 Humphrey McQueen, '"In for 'higher art' I'd go": At the National Portrait Gallery', Australian Book Review, May 2009, 41–3.

4 The Australian, 27 October 2009, p. 5.

5 Australian Financial Review, 13–15 November 2009, p. L9.

6 Quoted in Sarah Engledow & Andrew Sayers, The Companion: National Portrait Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, 2008, p. 3.

7 See Daniel Thomas, 'Australian portraits private and public', in Faigan (ed.), Uncommon Australians, pp. 11–17.

8 McQueen, '"In for 'higher art' I'd go"', p. 41.

9 ibid.

10 ibid., p. 42.

11 ibid., p. 43.

12 ibid., p. 42.

13 See National Portrait Gallery, Charter of Operations 2008/09 and Policy Guidelines for Development of the Permanent Collections.

14 See National Portrait Gallery, 'Gallery history', www.npg.org.uk/about/history.php.

15 Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, p. 33.

16 See Michael Ackland, Henry Handel Richardson: A Life, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004, pp. xv–xx.

17 I am grateful to Dr Nathan Garvey for this information conveyed in a personal communication, 23 November 2009.

18 See Nathan Garvey, The Celebrated George Barrington: A Spurious Author; the Book Trade, and Botany Bay, Hordern House, Sydney, 2009, p. 185. See also Nick Hordern, 'Barrington: Populist pickpocket', in the Australian Financial Review (Re/view), 4 September 2009, pp. 3–4.

19 Quoted in Rosemary Sorenson, 'Framing a nation', Weekend Australian Review, 29–30 November 2008, p. 5.

20 Quoted in Jim Davidson, 'Dame Nellie Melba', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol.10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, p. 479.

2 The Australian, 3 October – 1 November 2009, p. 3.

3 Humphrey McQueen, '"In for 'higher art' I'd go": At the National Portrait Gallery', Australian Book Review, May 2009, 41–3.

4 The Australian, 27 October 2009, p. 5.

5 Australian Financial Review, 13–15 November 2009, p. L9.

6 Quoted in Sarah Engledow & Andrew Sayers, The Companion: National Portrait Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, 2008, p. 3.

7 See Daniel Thomas, 'Australian portraits private and public', in Faigan (ed.), Uncommon Australians, pp. 11–17.

8 McQueen, '"In for 'higher art' I'd go"', p. 41.

9 ibid.

10 ibid., p. 42.

11 ibid., p. 43.

12 ibid., p. 42.

13 See National Portrait Gallery, Charter of Operations 2008/09 and Policy Guidelines for Development of the Permanent Collections.

14 See National Portrait Gallery, 'Gallery history', www.npg.org.uk/about/history.php.

15 Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, p. 33.

16 See Michael Ackland, Henry Handel Richardson: A Life, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004, pp. xv–xx.

17 I am grateful to Dr Nathan Garvey for this information conveyed in a personal communication, 23 November 2009.

18 See Nathan Garvey, The Celebrated George Barrington: A Spurious Author; the Book Trade, and Botany Bay, Hordern House, Sydney, 2009, p. 185. See also Nick Hordern, 'Barrington: Populist pickpocket', in the Australian Financial Review (Re/view), 4 September 2009, pp. 3–4.

19 Quoted in Rosemary Sorenson, 'Framing a nation', Weekend Australian Review, 29–30 November 2008, p. 5.

20 Quoted in Jim Davidson, 'Dame Nellie Melba', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol.10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, p. 479.

« back

::

next »