Abstract

Community museums have traditionally focused on a particular geographical location. This proximity between museums and the focus of their collection give them a unique opportunity to make connections between objects, the museum building, landscape, and community. These linkages are one of the key strengths of local museums due to their potential to tell inclusive stories of people and place. Australian Holocaust museums are displaced from this geographical proximity and situated at great distance from the events they commemorate. Due to the intense involvement of survivors in their inception and development, however, such museums have been driven, indeed, defined by communal imperatives. This paper examines the connections between community and place constructed through these museums. Further, it asks how community, place and the local are defined, and how and in what way the community museums examined make connections between here and there, then and now.

This paper takes as its focus two Holocaust museums in Australia: the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne and the Sydney Jewish Museum. After briefly exploring the origins of the respective institutions and the motivations of those involved, the paper discusses how the museums construct ideas of community and place, focusing particularly on the complex imaginative geography that creates intimate, emotional connections between different times and places.

Introduction

The museum reflects a habit of mind opposed to one that perceives place to be rooted, sacred and inviolable. The museum, after all, consists wholly of displaced objects. Treasures and oddities are torn from their cultural matrices in different parts of the world and put on pedestals in an alien environment.

Ti-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience[1]

The definition, role and appeal of community museums have been the subject of much recent debate.[2] Such discussions primarily focus on the relationship between museums and identity, particularly the ways in which museums create a sense of place – the way in which a space becomes invested with meaning through lived experience.[3] As Elizabeth Crooke, whose recent work has brought such issues in community museums to scholarly attention, argues, these museums can be seen as having a number of functions: for example, as a means for communication of a particular message, a disciplinary device for the inculcation of particular societal ‘norms’ and as a social space through which community members interact and mediate relationships within the community.[4] The question then becomes one of ‘definition, boundaries and belonging’.[5]

This paper provides an overview of recent debates about the relationship between museums, community and place, before examining these ideas in two community museums in Australia: the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne (JHC) and the Sydney Jewish Museum (SJM). It explores how the original sense of place created through the museum displays by the interaction of objects, narratives, location and visitor have changed over time in response to changing community concerns. These two museums are particularly interesting examples through which to explore issues of community, place and identity. They both incorporate narratives and material culture central to group identity, but which by definition reference places and events located elsewhere, away from the physical location of the museum. While the JHC focuses exclusively on the Holocaust, with Australian Jewish life represented in the nearby but separate and independent Jewish Museum of Australia (JMA), the SJM has a remit to tell stories both about the Holocaust and Jewish life in Sydney.

Museums, heritage and identity

The relationships between museums, heritage and identity have long been acknowledged at the national level. National museums have been understood as sites of identity formation, key locations through which narratives of the nation are produced and consumed.[6] Rather than the museum being seen as a site of inculcation of national identity, such research argues for a nuanced understanding of the role of the visitor, suggesting the active, affective experience of visitors who make and remake the museum according to their own needs and understandings. Museums are seen as ‘contact zones’ where such contact is ‘lived, negotiated and contested’.[7]

At the local level, museums can play similar roles and the growth in local museums in Australia in recent decades points to a growing interest in local heritage.[8] However, as Crooke argues, this ‘unofficial museum sector’ may have distinct characteristics.[9] Such institutions may be more transient, be personality driven, and respond to community needs and concerns, rather than the professional standards of the wider museum community.[10] As such, community museums reveal the complex set of relationships within groups as well as the relationship between the group and wider society. Further, ‘at both the local and national level, museums and community must be considered in relation to issues of identity, representation and the role museums have in constructing a sense of place’.[11] Within museum discourse this concept of sense of place is often taken for granted, an undefined shorthand for the social role of the museum and its relationship to local identity formation.

The creation of a sense of place, then, is seen as a crucial function of community museums.[12] Jennifer Barrett, whose work investigates the role of museums as sites of democratic public space, argues that community museums are spaces through which:

community becomes the embodied element of place, distinguishing it from space. Places are inhabited, lived in by people who, by the nature of their location, can become part of a community – knowingly or unknowingly.[13]

Despite the positive connotations of ‘community’, others have suggested a need to critique the normative, potentially exclusionary tendencies of community.[14] Within the museum sector, Barrett uses the work of sociologists Gordon Fyfe and Max Ross to draw attention to the question, ‘Whose sense of places are they to acknowledge?’[15] However, as Stephanie Hawke, whose research explores how heritage contributes to sense of place, has argued, even more recent ‘locals’ can create a sense of belonging and inclusion through the imagined connection with people and place, an ‘autobiographical insideness’ which allows these newcomers to feel part of the community.[16] Such autobiographical insideness may not be a product of time, but of the intensity of the affective experience of place, and: ‘while it takes time to form an attachment to place, the quality and intensity of experience matters more than simple duration’.[17]

Through this affective role in the creation of a sense of place, museums have long had a social role. This has intensified in recent years, not only through a broadening of the understanding of the role of the museum and an outward focus on the community, but also as a means of responding to government policies. Thus museums, and heritage sites more generally, are seen as a means of fostering social inclusion, educating ‘future generations’ and re-energising local economies through tourism and place promotion.[18] Indeed, consultant Elaine Gurian recently challenged the museum sector to go further and think about whether reframing the museum as ‘soup kitchen’ might offer some new ways of being of service to the community.[19] Whilst cognisant of recent criticisms that suggest museums and heritage are becoming ‘overburdened’ with this social role,[20] the museum does have an important function as a social space where shared and inclusive narratives of the ‘imagined community’ can be produced, experienced and negotiated.[21]

However, it is this stable sense of identity that is now conceived of as under threat and identities are now said to be in a state of flux.[22] If, as Gregory Ashworth suggests, globalisation, migration, travel and increased communication are resulting in evermore plural societies, what role does heritage play in the socialisation process, of people’s identification with place and community and the creation of a sense of place?[23] How can museums foster more fluid notions of belonging, in Crooke’s evocative conception, as a space for memory, rather than of memory and, perhaps we can suggest, as a space for identity, rather than of identity.[24] How can they play a role in the ‘intensification of experience’ through which people might develop attachment to place?

Holocaust museums, whose very reason for being is simultaneously about displacement, loss and belonging, also have an intense connection with people and places separated not only historically, but also geographically, and therefore might offer a way of thinking about community museums differently. How have these museums developed over time to respond to changing community needs? What happens to sense of place when the location of the museum and the places that it represents are separated by vast distances?

Sydney Jewish Museum

The original mission statement of the Sydney Jewish Museum (SJM), founded in 1992, proudly proclaims:

The Sydney Jewish Museum is a museum about a people. Created as a living memorial to the Shoah, it honours the six million who perished, the courage and the suffering of all those who were caught up and those who attempted to resist evil for the sake of what was right. We celebrate their lives, cherish the civilization that they built, their achievements and faith, their joys and hopes, together with the story of the Australian Jewish community and its culture.[25]

Seemingly inconsequential amid the aspirational sentiments surrounding it, it is the word ‘together’ that provides insight into the SJM’s sense of place. From its inception, and in line with its mission statement, the SJM contained two permanent exhibitions: the first focusing on the Holocaust and the second on Jewish life, tradition and culture, with an emphasis on the Australian Jewish experience. In so doing, the SJM sought to display two seemingly contradictory ideas of community at once: the destroyed communities of European Jewry and the relatively safe and prosperous history and contemporary reality of the Australian Jewish community. While the relationship between the two exhibitions has often been the topic of internal discussion, with the dilemma being that housing a Holocaust and general Jewish history in a single space might detract from an ‘integrated’ museum experience,[26] we argue that with regard to creating a ‘space for identity’ the opposite is the case; positing that it is precisely the juxtaposition of ‘then and now’ in the two permanent exhibitions that creates the SJM’s communal identity and sense of place in the present.

In conflating past and present the SJM displays allow for the mourning of communities lost and the celebration of communities found. Given that the SJM sees itself as a ‘meeting place’ for the Jewish and broader communities, connecting both the Jewish and Holocaust experience into the wider Australian experience has been a priority for the SJM Board since the museum’s inception.[27] However, in creating this connection, a somewhat idealised vision of community has resulted, wherein a once largely unwanted group of post-war migrants are firmly ensconced in a ‘welcoming’ vision of Australia: a vision of ‘home’ that bears little resemblance to the complex, often less-than-ideal lived reality of the post-war period. Thus, while communal identity is forged and space for identity is created in and through the SJM’s permanent exhibitions, what kind of identity is considered acceptable is firmly delimited. Indeed, what the following exposition demonstrates is that when such ‘acceptable boundaries’ are crossed, debate as to exactly what the SJM’s communal identity should entail inevitably results. Delineating these boundaries of place, identity and space lays bare therefore not only the SJM’s self-understanding of its identity but also the desired impact of that identity in the broader domain of Australian public life.

The composition of the SJM’s communal identity and sense of place can only be understood in the context of its rather unusual history. Unlike the Melbourne JHC, whose financing was sourced mainly from Holocaust survivors, in its early years the SJM was funded by a single benefactor, the late John Saunders, co-founder of the now-global Westfield department store chain with fellow survivor, Frank Lowy. In partnership with the Australian Association of Jewish Holocaust Survivors (AAJHS), [28] who agreed to provide the ‘manpower’ for the operation, Saunders’ support was the key factor in realising what had long been a dream of the AAJHS. Sydney survivors who had been inspired by the First International Gathering of Holocaust Survivors in Jerusalem in 1981, along with other factors such as the emergence of popular international representations of the Holocaust like the 1970s mini-series Holocaust in the 1970s, had already organised educational initiatives, including temporary displays in locations such as the Sydney Town Hall in 1981.[29] However, due to financial constraints and a lack of will from the wider community to raise funds for such a venture, it was only through Saunders’ financial backing that a permanent exhibition became a real possibility.

While Saunders’ patronage would ensure that the SJM would indeed eventuate, it also meant that Saunders himself would maintain a commanding (but not total) influence over the project. Working hand-in-hand with the AAJHS, whose membership would provide the majority of guides and general volunteers for the SJM, Saunders’ understanding was clear; he wanted to build ‘a yiddishe museum’, a museum that would focus on the Jewish experience.[30] What ‘yiddishe’ might have meant in this context is debateable, but Marika Weinberger, a founder of both the AAJS and the SJM, indicated that not only would the essential ‘Jewishness’ of the Holocaust experience be highlighted[31] but that Saunders’ desire to show his and other survivors’ gratitude to Australia would also be at the forefront.[32] These dual commitments would eventually come to be embodied both in the permanent Holocaust exhibition and in the ground floor permanent exhibition Culture and Continuity, a display that seeks to illustrate the Jewish commitment and contribution to the fabric of Australian life.

As Saunders and the AAJHS moved forward with their plans to build the SJM, the choice of a pre-existing communal building to house the museum further facilitated the achievement of these two goals. After some debate as to where it might be placed, the SJM was eventually built within the Maccabean Hall, known colloquially as the ‘Macc’, and located in the inner Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst. The building, opened formally on Armistice Day 1923 by the Australian-Jewish war hero Sir John Monash, also houses the New South Wales Jewish War Memorial. There was general agreement within the community at the time of building that a living communal centre would be the best way to commemorate those who served in the First World War. The walls of the forecourt are inscribed with the names of nearly 3000 Jewish Australian service people, including 177 who died serving in the Australian forces in the First and Second world wars.[33] The forecourt remains in its original form to this day and is the entry point for visitors, thus proclaiming the proud involvement of Jews in Australian history from the outset.

Indeed, the Macc was a vital part of Jewish life in Sydney. As the original 1992 SJM catalogue recounts:

The Macc instantly became a vibrant centre. There were meetings, dances, debates, revues, plays, movies, a library and a gymnasium. The hall housed High Holy Days services and a community Seder service at Passover. A singularly important flow-on effect was that countless marriages resulted from people meeting at The Macc.[34]

In 1965, the building was remodelled as the ‘N.S.W. Jewish War Memorial Community Centre’, and its focus changed from social events and activities to community administration. The arrival in Australia after the Second World War of the largest number of Holocaust survivors in proportion to the total population of any nation except Israel profoundly changed the landscape of the Australian Jewish community.[35] Yet, in their choice to house the museum in the Maccabean Hall, members of the survivor community, as represented by the AAJHS, placed themselves on a continuum with regard to the Sydney Jewish community’s sense of place, history and identity. By placing the SJM in the Macc, the survivors would add their experience to its history, grafting their own identity onto an already illustrious past. The built expression of this mission was eventually realised and, in 1992, with the Macc once more redesigned and refurbished, the Sydney Jewish Museum was officially opened.

Housing the SJM in the Maccabean Hall, therefore, served to create and reinforce the connection between the post-war survivors and the pre-war, largely Anglo-Saxon, Jewish community, despite historical evidence to the contrary.[36] Contained within the oldest Jewish communal site in New South Wales, the two experiences would be represented in the museum space as part of a continuous chain of Jewish involvement in Australian history. This unlikely marriage would be seamlessly achieved primarily in the ground floor permanent exhibition, Culture and Continuity, which would link the survivors’ understanding of their contribution to Australian Jewish life with earlier Australian Jewish history. This connection would be made principally through two displays contained within the exhibition: the first comprising a diorama of George Street in the 1840s and the second, an interactive exhibit entitled ‘Achievers’, focusing on outstanding individual Jewish contributions to Australian public life.

As a result of a redevelopment completed in 2008, Culture and Continuity now contains a much more complex and far-reaching exploration of Jewish history, tradition, culture and religious practices, with the section on Australian Jewish history also greatly expanded.[37] As part of the process of redevelopment, debate ensued as to whether the George Street diorama, containing historical inaccuracies and conveying little in terms of actual historical content, should be retained.[38] What was not up for debate, in the view of the SJM Board, was that the ‘Achievers’ section would not only be retained but would also be greatly expanded. With the SJM’s volunteers providing vocal and unequivocal support for the retention of both the George Street diorama and the ‘Achievers’ interactive, the two displays were indeed preserved and expanded.[39] Given both the Board’s and volunteers’ insistence on their inclusion, the significance of these displays to the SJM’s sense of place and communal identity cannot be underestimated.

reproduced with the permission of the Sydney Jewish Museum

The content of these two displays is telling: The colourful diorama exhibits a largely nostalgic view of Sydney’s main street in the 1840s. Jewish shopkeepers sit alongside other entrepreneurs, their integration into Australia’s colonial settlement seemingly unequivocal, and underscored by the displays opposite that explain that Australia’s first Jewish inhabitants were indeed part of the First Fleet. What was once known as the ‘convict stain’ is now cause for some pride in more popular versions of Australian history and the inclusion of such information in the SJM display is a source of pride for the Sydney community – illustrating involvement in Australian life from the origins of white settlement. Such an emphasis is not surprising if understood to illustrate a minority group’s desire to demonstrate its loyalty and connection to the majority population.

reproduced with the permission of the Sydney Jewish Museum

reproduced with the permission of the Sydney Jewish Museum

Strengthening this view of Australia as ‘welcoming’, and of Australia’s Jewish community as productive and loyal citizens, the ‘Achievers’ display is also at pains to demonstrate not only how the Jewish community found a welcoming home in Australia but also how individual Australian Jews made a fundamental and profound contribution to the fabric of contemporary Australian life. Figures such as First World War general, Sir John Monash, and Australia’s first Jewish governor-general, Sir Isaac Isaacs, are extolled alongside outstanding contributions from more recent survivor migrants such as Saunders, Lowy and artist Judy Cassab. While historically accurate, it is not the veracity of these stories that is of interest, but rather the emphasis of both displays on the themes of success and integration that are of most importance. The narrative created by the two sections is clear: Australia has always welcomed its Jews and continues to do so. In return, Australian Jews have been loyal citizens and outstanding contributors to Australian life.

Reinforcing the juxtaposition of ‘then and now’ and establishing the survivor experience firmly within a celebratory narrative, the final display of the permanent Holocaust exhibition, ‘Long journey to freedom’, documents survivors’ journeys and their rebuilding of their lives on Australian shores. Here the survivor generation is further extolled as an example of migrant integration par excellence. While this display mentions the discriminatory quotas imposed on Jewish migration by the Australian Government immediately after the Second World War, its emphasis is on the role that Australia played in providing a safe haven for survivors in the post-war period. Hence, the exhibition’s focus on Australia as a sanctuary for immigrant groups fleeing persecution – open, welcoming and largely cast in an idealised vision of contemporary ‘multicultural Australia’ – obscures other narratives. Apart from the panel on quotas, there is no indication of the recurrent xenophobia that has characterised Australia’s migration history and successive Australian governments’ rather chequered approach to refugees; nor is the fact that, while Holocaust survivors undertook the mammoth task of resettling in this country, systematic racial discrimination against Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations continued to take place.

Indeed, given that one floor above the permanent Holocaust exhibition begins and genocide becomes the focal point of the SJM narrative, the absence of any mention of ‘contact history’ is telling of the SJM’s current understanding of the links (or lack thereof) between the survivor experience and that of Australia’s Indigenous population. The one allusion to the dispossession of Sydney’s Eora people that occurred as a result of the settlement of Sydney, celebrated in the SJM diorama, is found only at the entrance to the museum, a ‘Welcome to country’ added at the time of the 2008 redevelopment. The SJM’s most recent plans for redevelopment[40] contain an explicit directive to address Australia’s treatment of its first peoples, but how this topic will be addressed remains to be determined.[41]

Despite this lack of reference to a broader framework of Australian migrant and Indigenous histories, ‘Long journey to freedom’ does chart the transformation of the survivor community from a largely unwanted migrant group in the immediate post-war period to a community at pains to celebrate its connection to and comfort with ‘the Australian way of life’. [42] Yet exactly how much information regarding post-war restrictions on Jewish migration should be displayed was hotly debated, with survivors reticent to display anything but gratitude toward a country that they perceived to have given them a chance at a ‘new life’. Indeed, the completed display, ‘Long journey to freedom’, narrowly escaped the subtitle ‘Thank you Australia’ but only at the insistence of the exhibition’s historical consultants, who felt that to retroactively ascribe such benevolence to a largely discriminatory migration policy would constitute a clear breach of historical accuracy.[43]

The clear emphasis of the George Street diorama, the ‘Achievers’ and ‘Long journey to freedom’ displays, therefore, is on inclusion rather than exclusion, on Australia’s integration and acceptance of the Jewish community from the inception of white settlement, rather than the recurrent xenophobia and racism that distinguished ‘White Australia’s’ stance toward both Indigenous and migrant populations for decades. Together, these three displays create a sense of place that works to harmonise disparate examples of place and community –separated in actuality by geography, time and changing communal identities. The largely celebratory sense of place they construct holds little possibility for the embrace of complexity and the investigation of other, ‘less comfortable’ narratives, even those that may have obvious thematic links, such as Indigenous genocide. However, with plans currently underway to expand the SJM’s permanent exhibitions and to include within this remit a dedicated ‘Human rights and the holocaust’ learning centre,[44] this narrative must by necessity be challenged, enlarged and reconfigured. If such an opportunity is fully embraced, the SJM may indeed transform its current sense of place and, in so doing, contribute to a critical museum discourse in which Australia’s migrant communities articulate and display more nuanced, and hence less nostalgic, views of both their past and present identities.

Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne

Unlike the SJM, whose focus is broadly on Australian Jewish life, Melbourne’s JHC, which opened in 1984, has a specific focus on the Holocaust. This is partly explained by the pre-existence in Melbourne of the JMA, which had opened in 1982,[45] but was also the result of several other key factors that illuminate its origins, structure and contribution to the creation of a sense of place.

In 2000, Melbourne had the largest Jewish Holocaust survivor community outside of Israel, with approximately half of the 100,000 survivors living in Australia residing in Melbourne.[46] Unlike Sydney’s Jewish Holocaust survivors, who originated primarily from Germany and Hungary, Melbourne’s post-1945 Jewish émigrés were predominately Polish. A Jewish community in Melbourne was already established by the 1840s, formed largely by British Jews[47] and, later, at the turn of the century, eastern European Jews.[48] In the 1980s, fears over the rise of Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism resulted in communal efforts to educate the wider public about racism and its consequences.[49] Even though Holocaust denier David Irving’s name was known worldwide, it was Melbourne right wing lawyer John Bennett, a member of the Victorian Council for Civil Liberties (VCCL), who claimed in 1979, amid other anti-Semitic allegations, that Auschwitz was a ‘normal’ concentration camp, which hastened the need to establish education about denialism and the Holocaust.[50] Although Bennett was subsequently expelled from the VCCL, the fact that attacks like these could come from within such organisations prompted Melburnian survivors to conclude that those who had born witness to the Holocaust – the survivors – had a duty to talk frankly about it. One response, and one that was to be a major catalyst for the establishment of Melbourne’s Jewish Holocaust Centre, was the 1980 Holocaust Exhibition, organised under the auspices of B’nai B’rith (the worldwide body that provides advocacy and policy for the Jewish community and fights anti-Semitism). Within the groups associated with the exhibition, two were to form the JHC: the Federation of Polish Jews (FPJ) and Yiddishist cultural organisation Kadimah.[51] Aron Sokolowicz, a Bialystok Polish Jewish survivor of Auschwitz and Ebensee, was president of the FPJ and a member of the Kadimah, and provided some of the memorabilia that was displayed in the exhibition. The exhibition, held in the Tramways Hall opposite the Royal Exhibition Building in Carlton, included an embryonic notion of the future permanent museum with a display of personal photographs, letters, and memorabilia. Participants even recorded some of the first oral testimonies of Australian Holocaust survivors. Approximately 7500 Melburnians attended, making it ‘at the time the largest and most comprehensive single exhibition devoted to the Holocaust ever staged in Australia’.[52]

As mentioned, Melbourne’s founding Jews were primarily Anglo-Saxon, but after the ‘failed revolution’ of 1905 in Russia and pogroms that swept across eastern Europe, many Jews escaped to Melbourne. This influx saw the beginning of disputes between the Hebraic and Zionist Anglo Jews and their predominately Russian and Polish counterparts, who, for the most part, were left-leaning, Yiddish-speaking, secular Jews.[53] The climate of disagreements and collaborations – in particular over issues to do with the Kadimah – was still prevailing when the diverse sections of Melbourne’s Jewish community came together to formulate a permanent museum.

The success of the 1980 B’nai B’rith Holocaust Exhibition encouraged some Holocaust survivors to support the establishment of a permanent museum. Although there was initial enthusiasm for a Holocaust museum to be developed under the leadership of the Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies (VJBD), Sokolowicz was already well advanced in his planning for a permanent exhibition. Indeed, in the late 1970s he had purchased a building in the Melbourne suburb of Caulfield with the help of the FPJ and commissioned architect’s plans for a museum.[54] However, a more attractive site became available, close to existing Jewish organisations. The location was an old dance hall in Elsternwick, nestled between the Kadimah and the Sholem Alecheim College. Unlike in Sydney, there was little discussion as to the appropriateness or otherwise of the site or its location but, given the close relationship between the Kadimah and the JHC, the advantages were clear. Involved with the initial discussion was Symcha Binem (Bono) Wiener, like Aaron Sokolowicz, a survivor of Auschwitz I, the president of the Bund (a Jewish socialist organisation, originating in Russia in the late 1800s). Meetings between the FPJ and the Kadimah began in March 1983 and, a year later, the JHC opened its doors.

The motivations for the JHC can be found in an early letter sent from the Executive Committee to potential supporters in 1983. The JHC, it was argued, would be a response to Holocaust denial, a ‘unifying factor for the surviving families’, and a ‘lasting tribute to the memory of the 1½ million Jewish children who died only because they were Jewish’. They continued: ‘The Holocaust Museum will prevent us from forgetting our tragic past and will strengthen our National watchfulness’.[55]

Sokolowicz and Wiener joined forces with Mina Fink, who had migrated from Bialystok to Australia in the 1930s. Mina was highly active in Jewish welfare during and after the Holocaust and was known as the ‘mother’ of the ‘Buchenwald Boys’, a group of Holocaust survivors who were incarcerated in the concentration camp and settled in Melbourne.[56] These three were instrumental in the founding of the JHC: Sokolowicz and Wiener were co-presidents and Fink served on the Board. She generously donated funds to help purchase and establish the permanent museum in the former Selwyn Street dance hall, renamed Leo Fink House in honour of her late husband.

reproduced with the permission of the Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne

Thus, both pre- and post-Holocaust refugees and migrants who formed the Yiddishist Kadimah and the FPJ provided time and money to start a Holocaust museum. This drive, from two disparate ‘non-mainstream Jewish community organisations’[57] meant that the JHC differed from the SJM in that it was community-based, financed and run, and its content concentrated solely on the Holocaust.

This is not to say that the possibility of a combined organisation in Melbourne was not considered. For example, as a result of the debates within the VJBD about the need for, and location of, a Holocaust museum in Melbourne, Avram Zeleznikow, the chair of the Jewish Heritage Committee of the VJBD, went so far as to search for possible locations. One such option was rooms in the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation’s synagogue, on Toorak Road, South Yarra. Ironically, the space had only recently become unavailable, occupied instead by the fledgling JMA, where it would remain for the next 13 years until it moved to a site in Alma Road, St Kilda. Despite some suggestions during the intervening years that the two museums should merge (including an approach to the JHC in 1985 by Rabbi Ronald Lubofsky, who had established the JMA), the physical and institutional separation of the two museums proved too great an obstacle for any merger to succeed.[58] While the JHC opened with a commitment to combat racism and educate the community about the Holocaust, this was combined with an explicit commemorative rationale that would again separate it from the JMA: a merger would mean that the commemorative function of the JHC would be subsumed by the JMA’s broader focus on Australian Jewish history.[59] The JHC was intended as a place for the survivors to mourn and grieve, both a memorial and a museum, and described by one Holocaust survivor volunteer as an ‘open grave’.[60] It was to be a place for survivors to talk to each other, feel active and open the door to anyone who wanted to listen to their experiences of the Holocaust. Given these aims, a significant emphasis was placed on attracting visiting school groups, particularly from non-Jewish schools.

Exhibitions have played an important role in the JHC’s development and mission since its inception. Indeed, the initial public focus on the JHC was related to the material culture on display. Sokolowicz, interviewed by the Australian Jewish News about the opening, highlighted the photographs, artefacts, documents and paintings that would be displayed. Objects included ‘Rumkies’ (ghetto currency), home-made scales to weigh food in the camp, whips and a Haggadah, all from the Lodz Ghetto, and two bars of ‘human’ soap.[61] The relationship between the permanent exhibition and commemoration was explicit in the article, with Sokolowicz pictured in front of a 1946 photograph showing him returning to the site of the Warsaw Ghetto as part of a commemorative service.

As with any museum, documents and artefacts were seen as central to the functioning of the JHC. Calls for donations of Holocaust ‘memorabilia’ in the article were repeated over the next 30 years and suggest the idea of the JHC as a resting place and as a collection of evidence, aligned to the JHC’s commitment to provide evidence against deniers and to preserve the ‘vanished world’, of Poland, in particular.

Little information remains to reconstruct the original museum, which was housed upstairs in Leo Fink House. The room was painted in a ‘sombre two-tone grey’ according to the Australian Jewish News[62] and featured large aluminium panels on which the exhibition was displayed. The exhibition primarily displayed photographs, some reproduced from books, others from family albums, with accompanying text labels, organised by theme and a smaller number of artefacts and documents in plastic boxes, attached to the panels.[63]

Text in the exhibition was generally confined to the identification of objects and photographs, and there was little in the way of contextualisation. For those who had direct experience of the events depicted, there was no need for explanation of the objects’ location within a wider Holocaust narrative. And, although the museum had as one of its aims to educate the wider community, the objects and photographs were left, not to speak for themselves, but to be interpreted by survivor guides. The internal and external focus of the museum was explicit in the use of English and Yiddish captions: both languages of home, old and new. The exhibitions changed very quickly after the opening of the JHC to incorporate material on pre-war Jewish life in Europe. A review of operations in June 1985 by Dr Geulah Soloman, president of the National Council of Jewish Women Australia, prompted further changes. Soloman was unreserved in her admiration for the volunteer guides, but did comment, however, on the ‘natural dominance’ of information related to Polish Jewry in the exhibition and recommended that material on Jews from other countries should be collected, which eventually was included in future permanent exhibitions.[64] In 1985, Saba Feniger, a Holocaust survivor and volunteer, became the JHC’s curator and, over the next two decades, had a profound impact on the development of the exhibitions. The opportunity for a major expansion in 1990 provided the impetus for changes to the exhibitions, led by Feniger. The main exhibition moved downstairs in Leo Fink House, allowing a large auditorium upstairs.[65] Contrasting with the grandness and beauty of the SJM, a previous curator and director of the JMA summed up the differences between this new exhibition and the SJM:

The Melbourne museum lacks the sophistication of its Sydney counterpart. Most of its displays are hand made. But to me that is their unique power. The museum is a product of love and devotion and of memory, an intensely personal monument from the survivors to their peers.[66]

Although minor changes took place over the next 20 years, this exhibition remained substantially intact until 2010. Of particular importance to discussions of sense of place are two key themes in the JHC’s permanent exhibition: the representations of pre-Holocaust Jewish life in Poland and the survivors’ new life in Australia. The first panel in this new exhibition was a collection of family photos under the title ‘The vanished world’. The photographs were donated to the JHC by the volunteers, creating the ‘intensely personal’ memorial space through their display.

An introductory text explained that many of the images were of family members of survivor guides who now worked in the museum. Some of the photographs were unattributed. Due to the importance of the photographs as witness to the vanished world, these photographs were sometimes out of place, referencing events outside of the exhibition chronology. For example in ‘The vanished world’ section that depicted life in Europe before the Holocaust, one photograph showed survivor volunteer Stephanie Heller wearing a yellow star during her wedding to Egon Kunewalder in Prague in 1942. Another showed Lieutenant Leon Mendelewicz (who was on the Executive Committee of the JHC at the time the photograph was first displayed) leading a victory parade in Zamosc, Poland, in 1947. The familiar museum problem of the partiality of the material culture record to be able to illustrate particular themes was exacerbated by the particular historic circumstances: personal narratives took precedence over established geographies and histories of the Holocaust.

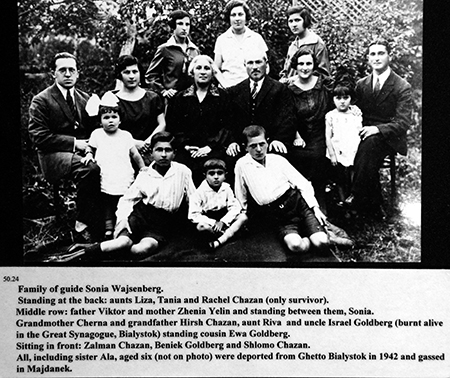

original photograph donated by Sonia Wajsenberg and photograph of panel reproduced with the permission of the Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne

Many photographs revealed a double absence: those who not only were killed during the Holocaust, but who are also missing from the photograph. An example from the exhibition is a photograph of the family of survivor and volunteer Sonia Wajsenberg. Sonia’s photograph and the accompanying caption are typical of most of the exhibits in ‘The vanished world’. In Jewish tradition, a name or the act of naming is inviolable and the imperative to name relatives is as important as displaying the photographs depicting the cultural world and the loved ones who inhabited it.[67] In addition, by including the location of the relative’s murder, this technique highlights the importance of memorialisation in the early exhibits and their contribution to ‘proof’ of the events that came after.[68] Rather than errors, these examples are fundamental to understanding the poetics of display in the museum and the connotations of the relationship between personal and collective narratives. The exhibition had a personal rather than a museological imperative: provenance was less important than the role the photographs had in creating a sacred space to remember lost loved ones.

As we have seen, a key narrative in the SJM is the continuity between the established Australian Jewish community and the new post-war migrants. Given that the two Melbourne museums have separated between them the Holocaust narrative and the broader Australian Jewish history, it is unsurprising that little mention is made in the JHC’s exhibitions to a wider Australian Jewish history such as is found in the SJM’s Culture and Continuity. The need to document what was lost was more important than the need to tell the stories of what happened on and after arrival. Even though migration stories were part of the later changes to the exhibition, they came about through the development of temporary exhibitions rather than as an integral part of the original exhibition.

For example, the initial theme considered for a temporary exhibition at the JHC marking the bicentenary of European settlement of Australia was similar to that of the SJM’s exhibition, focusing on ‘prominent Jews in the history of Australia over the last 200 years’. However, this changed to a focus on the survivors themselves, in an exhibition entitled: From Holocaust to New Life, which explored the contribution of 16 Holocaust survivors to the Australian community. The exhibition was intended to tell a positive story that:

focused on the survivors’ contributions to Australian society and economy, rather than their wartime experiences; those who achieved prominence in various spheres, including community work, education, music and science. Jewish survivors who not only established themselves as useful, law abiding citizens but also contributed to the society that adopted them.[69]

Another key component of JHC’s bicentennial exhibition became part of the permanent exhibition, an ‘eye catching logorama’, designed by Charlotte Neumann and produced by Charles Rever, depicting the journey of survivors moving from Europe to Australia, with ‘optic fibres light[ing] up in a sequential manner, showing the movement of the masses leaving Europe and eventually merging into a brightly lit Australia’.[70] Placed at the entrance to the exhibition, it disrupted the strict chronology of the representation of the Holocaust and provided a comforting narrative that contradicted the mourning and memorialisation present in the rest of the exhibition.[71]

Another panel in the permanent exhibition relating to Australian life was also developed as part of a 1998 temporary exhibition, Regeneration. Part of the ‘Australian families’ project,[72] it was a display of one family’s story, from before, during and after the Holocaust, when those members who survived moved to Australia and began a new life. The design of the panel was in the shape of jigsaw puzzle that, due to the Holocaust, could never be completed, disrupting the more positive connotations of regeneration and ‘new life’ presented in the optic fibre display.

photograph by S Cooke

In 2010 the permanent exhibition space at the JHC underwent a major, award-winning redevelopment and, although the major exhibition themes remained virtually unchanged, the display techniques and content were updated. While the exhibition may have lost some of its ‘unique power’ through its transformation into a modern museum space, new technologies, such as ‘storypods’[73] allow personal narratives to be included, without disrupting the conventional historiography of the Holocaust. From its beginnings as an ‘open grave’, the current executive director and head of research, Warren Fineberg, now describes the JHC as a ‘healing centre’, not only for the Jewish community, but also the broader community, indicating the museum’s growing commitment to recognise the broader Australian community and victims of other genocides.[74]

Conclusion

The two museums discussed in this paper can both be described as community museums, but they display different communal responses to the challenge of Holocaust commemoration and education. The SJM provides a continuum between pre- and post-war Jewish communities in Australia, whereas, due to its origins and history, the JHC places more emphasis on the need to recreate a lost world, a need also evidenced by the importance of collecting testimonies at the JHC.[75] The links to Australia, although evident in the JHC exhibitions, foreground notions of loss and absence, disrupting the more positive connotations of ‘new life’.

In combination, the building and displays of the SJM create a sense of place for survivors and the broader Sydney Jewish community, in which Australian Jewish loyalty and contribution is manifest and located on a continuum with a past now largely recast as celebratory. In so doing, the SJM acts as an example par excellence of the struggle for Australia’s migrant communities to remember what was home, while demonstrating a commitment and connection to what is home. Complexity is retained where historical accuracy demands it, but the more subtle comparative work that would require a more nuanced understanding of the difficulties of migration and its relationship to broader issues of race and nation in the Australian context are yet to be explored. Perhaps once such subtlety is achieved, the SJM can truly become a place for identity, where that identity is explored in all its complexity and where difficult but important issues are presented and debated in communal space; allowing Australia’s migrant communities to truly participate in, and not simply ‘contribute’ to, Australian public life.

In the JHC, the ‘then and now’ concepts have been less easily defined in the permanent museum, as evidenced in the photographs in ‘The vanished world’ display. The ‘then’ became fused into the ‘now’. Through the disruptions in the former ‘vanished world’ chronology, the museum made explicit the local connections to the Holocaust, an event that can seem vast and unimaginable, materially and symbolically distant in time and space. Through the stories of survivors and their families that are no more, the museum brought the Holocaust closer to the imaginative world of the visitors – they are the stories of people in our community, and have the potential to elicit more searching questions about our relationship with the Holocaust.

The JHC and the SJM reference events and places that are far removed from the location of the museum. What our examination of ‘sense of place’ in Australia’s Holocaust museums highlights is the need for a more nuanced understanding of ‘place’ in community museums, one that embraces notions of ‘gaps’ and non-linear narratives rather than of fixed notions of identity and community. In an increasingly globalised and mobile world, where notions of community are often imagined and experienced as transient, fluid and contested, the challenge is to both experiment with ‘other ways of storying landscape, [that] fram[e] histories around movement rather than stasis’[76] but that also acknowledge the intense, affective relationship with place that can be embodied in community museums. Despite the perception of museums as embodying ‘place [as] rooted, sacred and inviolable’, contradicting the ‘habit of mind’ which foregrounds questions of mobility and the relationships between people and places, it is clear through the changing nature of the two Holocaust museums in Sydney and Melbourne that they can be both.

Endnotes

The authors would like to thank the Sydney Jewish Museum, the Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne, and the Australian Jewish Historical Society for access to the VJBD archives.

1 Ti-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, Edward Arnold, London, 1977, p. 194.

2 Jennifer Barrett, Museums and the Public Sphere, Wiley-Blackwell, New York, 2011; Elizabeth Crooke, Museums and Community: Ideas, Issues and Challenges, Routledge, Hoboken, 2008; Elizabeth Crooke, ‘Community biographies: Character, rationale and significance’, in Kate Hill (ed.), Museum and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2012; Kimberley Webber, Liz Gillroy, Joanne Hyland, Amanda James, Laura Miles, Deborah Tranter & Kate Walsh, ‘Drawing people together: The local and regional museum movement’, in Des Griffin & Leon Paroissien (eds), Understanding Museums: Australian Museums and Museology, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2011, nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/KWebber_etal_2011.html, accessed 4 July 2013; Sheila Watson, ‘History museums, community identities and a sense of place: Rewriting histories’, in Simon Knell, Susanne MacLeod & Sheila Watson(eds), Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and Are Changed, Routledge, Hoboken, 2007.

3 Tuan, Space and Place.

4 Crooke, Museums and Community, p. 137.

5 ibid.

6 Steven Cooke & Fiona McLean, ‘Constructing national identity within the new Museum of Scotland’, in David Harvey, Rhys Jones, Neil. McInroy & Christine Milligan, (eds), Celtic Geographies: Landscape, Culture and Identity, Routledge, London and New York, 2001.

7 Phillip Schorch,‘Contact zones, third spaces, and the act of interpretation’, Museum and Society, vol. 11, no. 1, 2013, 68–81.

8 Webber, Gilroy, Hyland et. al., ‘Drawing people together’.

9 Crooke, Museums and Community, p. 8.

10 ibid., pp. 8–9 .

11 ibid., p. 15.

12 This of course happens, not only through formal or official museum or heritage sites, but also working through more ordinary or mundane spaces. See David Atkinson, ‘The heritage of mundane places’, in Brian Graham & Peter Howard (eds), The Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, Ashgate, London, 2008, pp. 381–95.

13 Barrett, Museums and the Public Sphere, p. 22.

14 David Smith, ‘Geography, community, and morality’, Environment and Planning A, vol. 31, no. 1, 1999, 9–35.

15 Gordon Fyfe & Max Ross, ‘Decoding the visitor’s gaze: Rethinking museum visiting’, in Sharon Macdonald & Gordon Fyfe (eds), Theorizing Museums, Oxford and Cambridge, MA, 1996, pp. 127–50, and Barrett, Museums and the Public Sphere, p. 9.

16 Stephanie K Hawke, ‘Heritage and sense of place: Amplifying local voice and co-constructing meaning’, in Ian Convery, Gerard Corsane & Peter David (eds), Making Sense of Place: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2012, p. 240.

17 Tuan, Space and Place, p. 198.

18 Gregory Ashworth, ‘Heritage in ritual and identity’, in C Brosius & KM Polit (eds), Ritual, Heritage and Identity: The Politics of Culture and Performance in a Globalised World, Routledge, New Delhi, 2011.

19 Elaine Gurian, ‘Museum as soup kitchen’, Curator, vol. 53, no. 1, 2010, 71–85.

20 Ashworth, ‘Heritage in ritual and identity’.

21 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso, London and New York, 1984.

22 Cooke & McLean, ‘Constructing national identity’.

23 Ashworth, ‘Heritage in ritual and identity’, p. 31.

24 Crooke, Museums and Community’.

25 Sydney Jewish Museum Mission and Vision Statement, Sydney Jewish Museum Institutional Archives, Sydney, 1992.

26 This discussion most recently resurfaced in the development of the internal Exhibition Concept Development plan that forms the basis for the SJM’s upcoming redesign of the Holocaust exhibition. See Avril Alba & X2 Design, Exhibition Concept Development Plan 2013, Sydney Jewish Museum, Sydney, 2013, pp. 13–14.

27 SJM Capital Appeal Brochure, Sydney Jewish Museum, Sydney, 2012.

28 In 1994 the organisation would change its name to include ‘Descendants’: an explicit recognition of the need for intergenerational transmission, becoming the Australian Association for Jewish Holocaust Survivors and Descendants (AAJHS&D).

29 Marvin J Chomsky (dir.), Holocaust, television miniseries, USA, 1978.

30 Interview with Marika Weinberger by Avril Alba, 11 October 2009.

31 Indeed, it was not until its most recent Master Plan (2013) that an explicit directive to include other victims in the main display was inserted after considerable debate. Avril Alba & X2 Design, An Obligation to Remember, Masterplan 2020, Sydney Jewish Museum, Sydney, 2013, p. 14.

32 Interview with Marika Weinberger.

33 For more information on Australian Jewish participation in the First and Second world wars see Suzanne Rutland, Edge of the Diaspora, Brandl & Schlesinger, Sydney, 1997, pp. 133–4, 273–4.

34 Gael Hammer, Sydney Jewish Museum Catalogue, Sydney Jewish Museum, Sydney, 1992, p. 7.

35 For a summary of the rise of popular Holocaust consciousness in Australia, see Judith Berman, Holocaust Remembrance in Australian Jewish Communities, 1945–2000, University of Western Australia Press, Crawley, 2001.

36 Indeed, strongly Anglophile in its outlook prior to the coming of the refugees, the established Australian Jewish community was not, at first, predisposed to the idea of a Holocaust memorial museum in Sydney: interview with Marika Weinberger. For an overview of the make up of the pre-war community, see Suzanne Rutland, Edge of the Diaspora, pp. 141–224.

37 The expansion was based upon the research of Suzanne Rutland, a specialist in Australian Jewish history.

38 Alba was the project manager and co-curator of the refurbished Culture and Continuity exhibition and was therefore intimately involved in the debates as to if and how these two displays were to be retained. See SJM Institutional Archive, Ground Floor Redevelopment Brief, Sydney Jewish Museum, Sydney, 2006.

39 While the diorama was retained, all other aspects of that section of the display were reconfigured, fixing many historical mistakes and filling gaps evident in the exhibition’s first incarnation.

40 See Alba & X2 Design, An Obligation to Remember; Alba & X2 Design, Exhibition Concept Development Plan 2013.

41 While the MasterPlan and Exhibition Concept Development Plan note that Indigenous experiences will be addressed in the new Holocaust permanent exhibition the exact content, placement and method of display are yet to be determined.

42 The negative public outcry that influenced government restrictions and quotas on post-war Jewish migration is fully explicated in Rutland, Edge of the Diaspora, pp. 233–56. Despite these restrictions, Australia still received the largest per capita influx of Holocaust survivors after Israel: ibid.,p. 256.

43 The consulting historians for the exhibition were Suzanne Rutland and the SJM’s resident historian Konrad Kwiet.

44 Avril Alba & X2 Design, An Obligation to Remember, p. 20.

45 Helen Light, ‘A home of Jewish culture and civilisation: Rabbi Lubofsky and the Jewish Museum of Australia’, in Anna Blay (ed.), Eshkolot: Essays in Memory of Rabbi Ronald Lubofsky, Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, 2002, pp. 4–14.

46 Jewish Holocaust Centre, ‘Aron Sokolowicz’, Jewish Holocaust Centre, http://www.jhc.org.au/aron-sokolowicz.html, accessed 3 July 2013; Judith E Berman, ‘Holocaust museums in Australia: The impact of Holocaust denial and the role of the survivors’, Journal of Holocaust Education, vol. 10, no. 1, 2001, 67–88 (p. 69).

47 Melbourne Hebrew Congregation, ‘Beginnings’, Melbourne Hebrew Congregation, www.melbournesynagogue.org.au/Templates/History_Beginnings.html, accessed 22 July 2013.

48 Alex Dafner, ‘The “Kadimah” 1911–2013 president’s message’, Jewish Cultural Centre & National Library ‘Kadimah’, http://home.iprimus.com.au/kadimah/k90eng.htm, accessed 15 July 2013.

49 This is not to deny, however, the many commemorative activities, including temporary exhibitions, that took place in Melbourne and elsewhere between the end of the Second World War and the early 1980s.

50 Berman, ‘Holocaust museums in Australia’ (p. 71).

51 ‘Kadimah’ means ‘progress’ or ‘forward’. It is the Melbournian Yiddishist cultural organisation, established in 1911 and continuing today. Although initially established in the inner northern suburbs of Melbourne, in 1972 the Kadimah eventually relocated to the more affluent inner south-eastern suburbs, to which the majority of Melbourne’s Jews had moved. While being closer to its community was one attraction, the other was availability of Melbourne’s oldest cinema theatre, which backed on to the Kadimah’s new premises. This allowed the cultural centre to continue to stage its unique Yiddish Melbourne theatre performances.

52 Berman, ‘Holocaust museums in Australia’ (pp. 72–3). This exhibition, as mentioned earlier in this paper, was subsequently held in the Sydney Town Hall in 1981, where it attracted even larger audiences.

53 Dafner, ‘The “Kadimah”’.

54 Cyla Sokolowicz, ‘Aron Sokolowicz (1911–1991): Profile of a leader’, in Stan Marks (ed.), 10 Years: Jewish Holocaust Museum and Research Centre Melbourne, Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne, 1994.

55 Jewish Holocaust Centre, Minutes of the JHC Executive, 22 November 1983, JHC Archives.

56 Andrew Markus, ‘Fink, Miriam (Mina) (1913–1990)’, in Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra, 2007, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fink-miriam-mina-12493/text22475, accessed 15 July 2013.

57 Berman, ‘Holocaust museums in Australia’ (p. 72).

58 For a discussion of housing a Holocaust centre at the Toorak Synagogue, see Letter, Zeleznikow to Management – Melbourne Hebrew Congregation, 9 September 1981, and the reply, from Ronald Abel (executive secretary of Melbourne Hebrew Congregation) to Zeleznikow, 24 September 1981, Jewish Heritage Committee of the Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies (VJBD), General Correspondence 1982, 1983 VJBD Archives, MS 9352Y, Box 81. For discussions about the need for a joint communal approach to a Holocaust museum, see the debates at the VJBD Executive Committee during 1982 and early 1983, Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies Executive Committee Minutes, 15 February 1982; 31 May 1982; 22 November 1982; 14 February 1983, State Library of Victoria, Victorian MS 9352Y, Box 81.

59 Berman, Holocaust Remembrance, p. 7.

60 Kitia Altman in Berman, ‘Holocaust museums in Australia’ (p. 74).

61 ‘Memorial’s grim source’, Australian Jewish News, 17 February 1984, p. 7; Tsevi Shtal, Jewish Ghettos’ and Concentration Camps’ Money (1933–1945), D Richman Books, London, 1990; Jewish Virtual Library, ‘Lodz ghetto: History and overview’, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/lodz.html, accessed 7 July 2013.

62 ‘Memorial’s grim source’.

63 Saba Feniger, personal communication, Andrea Witcomb & Linda Young, April 2009.

64 Geulah Soloman, Centre News, 1985, p. 2; Dalia Sable, ‘Farewelling a Melbourne matriach’, 28 May 2010, www.jewishnews.net.au/farewelling-a-melbourne-matriarch/13670, accessed 30 June 2013. Although there were no significant changes in the exhibitions, this broadening did happen in the collection of testimonies.

65 The exhibition would remain essentially the same, albeit with a number of small but significant changes, until a major redevelopment in 2010.

66 Helen Light in Berman, ‘Holocaust museums in Australia’ (pp. 73–4).

67 This is specifically pertinent in the standing Jewish prayer, the shemoneh esreh, which honours the sanctification of the name.

68 This is also evident in many oral Holocaust testimonies, especially the video testimonies at the JHC, where the interviewer often asks the survivor to speak the full name of a relative.

69 Marks, 10 Years.

70 ibid., p. 44.

71 When the exhibition was redeveloped in 2010, the logorama was moved to the final section of the exhibition. Some exhibits have remained, particularly the artwork and the model of the Treblinka death camp by survivor Chaim Sztajer: see Andrea Witcomb, ‘Remembering the dead by affecting the living : The case of a miniature model of Treblinka’, in Sandra H Dudley (ed.), Museum Materialities : Objects, Engagements, Interpretations, pp. 39–52, Routledge, New York, 2010.

72 Culture Victoria, ‘The Australian Family project website’, www.cv.vic.gov.au/stories/the-australian-family/9282/the-australian-family-project-participants, accessed 17 June 2013.

73 [www.jhc.org.au/museum/our-museum/storypods.html, accessed 21 January 2014.

74 Warren Fineberg, personal communication with Donna-Lee Frieze, November 2012. This also represents a shifting of the non-universalist narrative that has been the dominant discourse within Australian Holocaust remembrance: Berman, Holocaust Remembrance, p. 7.

75 The JHC houses archives, a library and, since the 1990s, a dedicated video studio for filming Holocaust survivor testimonies. The SJM has also undertaken extensive recording on video of its survivor volunteers in a project called ‘Project 120’. Taping began during the 1990s but was digitised and re-edited to a three-hour length production for inclusion in the SJM display in 2005–06. The SJM also holds all of the Australian survivor testimonies from the (originally Steven Spielberg) Shoah Foundationcollection. The JHC has ‘self-help’ groups such as the Second Generation formation and a Child Survivor group. The Sydney child survivor group is independent from the museum but has connections to the SJM. There is a monthly ‘self help’ type group, formed in about 2007, run by the museum with clinical psychologist Renee Symonds to help survivors with the emotional burdens of volunteering at the museum.

76 Catherine DeSilvey, ‘Making sense of transience: An anticipatory history, Cultural Geographies, vol. 19, no. 1, 2012, (31–54).