Going social: A case study of the use of social media technologies at Te Papa

Introduction

The use of social media by museums has become a hot topic in recent years as museums have had to adapt to and grapple with the opportunities and challenges presented by new technology for engaging with active online publics. Social media has been described as one of the defining issues for museums in the 21st century, as they now need to operate across their physical site and the online world.[1] It is therefore crucial that we know more about the impact of social media on cultural institutions and how they should practically go about incorporating social media into their programs. Yet the literature on social media and museums is still developing, and there is a notable absence of empirical research about current professional practice in New Zealand. This article attempts to address this gap by exploring the use of social media at New Zealand's national museum, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa).

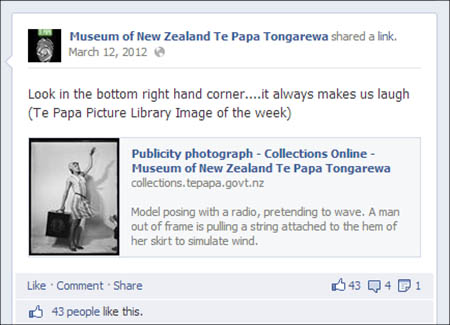

photograph courtesy Te Papa

As an area of research, the topic of social media and museums is relatively new. There are therefore few scholarly papers produced on the subject within museum studies that examine current practice, as distinct from media studies and related fields where museums are a popular site for theorising.[2] What has been written has come largely out of museum visitor studies and museum education, and has been led by the work of Angelina Russo and Lynda Kelly, who have worked on and in Australian museums. No detailed case studies of social media use by New Zealand museums appear to exist at this time.[3] Anthropologist and media scholar (and practitioner) Juan Salazar highlights the fact that, while recent literature has examined the emergence and impact of social media and social networking and how these new forms of communication have opened up spaces for participation and co-creation, 'very few analyses go beyond the new promises of networked socio-technical communities'.[4]

According to scholars publishing in this area, social media challenges traditional one-to-one and one-to-many communication models that in the past have 'provided the framework for authoritative cultural knowledge as provided by museum programs'.[5] This authority has historically been derived from 'the primacy of object collections and the patrimony of the museum in their storage, display and interpretation'.[6] Russo, Watkins, Kelly and Chan argue that this shift in cultural practice, while initially seeming to undermine the primacy of objects, can actually extend authenticity as provided by the museum 'by enabling the museum to maintain a cultural dialogue with its audiences in real time'.[7] They give the example of the Sydney Observatory blog, which in 2006 was used to dispel rumours that the planet Mars would pass exceptionally close to Earth on 27 August. In July 2006 the senior curator at the Observatory posted that this was a hoax. He received 135 responses over the next month crediting the Observatory with providing the 'truth' in the matter. According to Russo, Watkins, Kelly and Chan, this demonstrates 'how the many-to-many model can enhance both audience interaction and experience and museum authority'.[8]

Social media can also be used to enhance collection information by 'crowdsourcing', a term frequently used to refer to the practice of obtaining services, ideas or content by soliciting contributions from a large group of people, typically via the internet. This is becoming particularly applicable now that many museums are beginning to publish large proportions of their collections online. Proctor provides an example from the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney where, in 2009, a member of the public helped to identify an object from the collection after viewing it on the Museum's website. The object was an H7507 Inclinometer (also called a dipping compass or dip needle), made by Gambey, Paris. Sharon Rutledge, who has conducted research into the Paramatta Observatory, contacted Nick Lomb, curator of astronomy, with information that a Gambey dip circle had been listed in the 1825 and 1847 lists of Parramatta instruments as well as being mentioned in research papers on magnetism by observatory staff.[9] As a result, a week later the record incorporated the object's history, significance, and the story of its rediscovery in the Powerhouse collection.[10]

Russo, Watkins and Groundwater-Smith argue that social media 'can take a central role in learning in informal environments such as museums' as it offers 'young people agency previously unavailable ... in order to explore complex responses to and participation with cultural content'.[11] This is the case for the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, which has used non-publicised blogs to support onsite teen workshops and classes. The blogs include curricula and multimedia projects and 'serve as a place for teachers and teens alike to submit audio comments'.[12] According to digital media director at MOMA Allegra Burnette and museum education consultant Victoria Lichtendorf, 'the teens gain a sense of ownership and involvement, and, because of the blogs' internal focus, can express themselves unfettered by issues such as copyright and moderation – two issues which museums often grapple with'.[13]

Matthew MacArthur, director of new media at the National Museum of American History, believes that there are a number of key principles of museum learning that can be addressed 'by the thoughtful application of Web 2.0 methods'.[14] These include the fact that 'visitors do not typically view museums as classrooms for in-depth learning so much as smorgasbords of content with which to construct their own meaning and associations based on individual interests and backgrounds' and that objects can tell many stories and 'visitors may be well served when museums facilitate informed discussion incorporating multiple points of view'.[15] The importance of social interaction in museum learning is also discussed.[16]

Social media has also been used in exhibition development. In 2009 the Australian Museum used social media as a front-end evaluation tool to revise and redevelop content and themes for an exhibition on the topic of evil. Initially, an exhibition development blog was established using Blogger, a free online blogging tool. Later, an 'All about evil' Facebook group was created. In comparing the two approaches, the museum found that 'the blog seemed to be more of a 'reader space' – Google Analytics demonstrated that people were reading the blog, even if they didn't contribute – 'rather than a 'commenting space', with Facebook providing more discussion and interaction'.[17] The museum concluded that social media was 'an easy and efficient way to elicit feedback and dialogue at no actual cost apart from a maximum time investment of two hours per week'.[18]

While social media offers ways of reaching out to audiences, it also presents challenges around representation and control. Amelia Wong, at that time the Holocaust Museum's senior social media strategist, has written about the tension and synergy of social media in relation to modern museum practice, particularly with regard to ethical issues such as control, authority, ownership, voice and responsibility. Her experience of using social media at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is that it required imposing controls that oppose constructs of the new museology and the post museum in order to preserve the Museum's memorial and educational functions. For example, the museum deletes any comments on its YouTube channel that constitute 'vulgarity, derogatory language, outright abuse, Holocaust denial and off-topic rants', in the interest of 'trying to prevent the spread of misinformation, hate, and inanity, as well as to shape a space for potential dialog that has a modicum of civility'.[19] This amounts to a form of censorship and raises some interesting questions about free speech. Free speech as a constitutional ideal 'was intended to encourage democratic citizenry by creating public forums that expose people to diverse individuals and arguments on which they can deliberate'.[20] By not exposing people to the full range of responses, Wong wonders whether they are 'undermining the museum's aim to provoke critical thinking'.[21] She believes that 'determining ethical ways to respond will require continued participation and experimentation in the space'.[22]

The literature review revealed a need for more in-depth local analysis of current social media use within everyday museum practice. Therefore, the main aim of my research was to examine how social media was being used by New Zealand's National Museum, Te Papa, and any issues raised by this more participatory approach to communication. In terms of research design, I decided to focus on a single museum in order to look at how social media was being implemented across all aspects of the Museum's day-to-day business and public programs. My aim was to address the impact of social media on the organisation as a whole, in response to the survey of the academic literature that suggested that while individual case studies of specific projects have described and praised innovative ways of engaging with audiences, the broader implications of this for the organisation have not necessarily been considered. I employed current social science research methodology for the study, with key informant interviews conducted using the standard methods for data gathering, analysis and ethics.[23] So as to provide a cross-institutional perspective and to address the research question, I interviewed seven Te Papa staff, drawn from the areas of marketing, the Te Papa Picture Library, collections and research, exhibitions and concept development and information technology (IT).

Background: social media at Te Papa

Te Papa is New Zealand's national museum, located in the capital city of Wellington. Opened in 1998, it is the successor to variously named national institutions going back to the Colonial Museum, founded in 1865. Having been established through the integration of the former art gallery and museum, it contains a range of collections including art, history, natural history, Māori and Pacific, and has earned a reputation for innovative approaches, including interactive multimedia displays, to the visitor experience. Te Papa is an autonomous Crown entity that operates under the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Act 1992. The Act outlines the Museum's purpose, which is 'to provide a forum in which the nation may present, explore, and preserve both the heritage of its cultures and knowledge of the natural environment'.[24] The Act also outlines Te Papa's functions, a number of which can be applied to the museum's use of social media. These are 'to act as an accessible national depository for collections', to 'conduct research into any matter relating to its collections or associated areas of interest and to assist others in such research', 'to provide an education service', and to 'disseminate information relating to its collections, and to any other matters relating to the Museum and its functions'.[25]

Te Papa has been actively using social media for approximately seven years. Its first Flickr account was created in July 2007, followed shortly afterwards by a YouTube account in December of the same year. The Te Papa blog was launched in March 2008 and the Museum's Facebook page in December 2008. By late 2011, when I first started researching this topic, there were no internal guidelines or policies governing the use of social media at Te Papa.

Promotion, education and collaboration

Today, the use of social media at Te Papa is both varied and ubiquitous. Social media is extensively used to market exhibitions, events and public programs. According to Phillipa Ward, digital marketing executive, 'If you've got the people to do it then [social media] is a really cheap way of marketing'. It is also more engaging in that 'people interact with it' and you can give them repeated exposures. Ward likes the sharing aspect because 'rather than advertiser you can do it in a way that makes you more like their friend sharing cool information'. In this way she feels that it is an ideal way to 'subtly sell things'. However, the key is to create good content, 'anything that can excite [people] online, but then get them in action'. It is interesting to note that Ward still considers social media to be a supplement to more traditional modes of advertising, such as billboards, stating that 'it's more about complementing it than replacing it at the moment'.

Similarly, the Te Papa Picture Library uses social media as a way to raise awareness of the business. The picture library supplies copies of images from Te Papa's collection for educational and commercial use. Its aim is to recover costs, grow the business and ultimately make a profit. There is a sliding scale fee structure based on intended use. With a small marketing budget, Becky Masters, picture library manager, sees social media as a 'savvy' way to achieve being 'top of mind' when the time comes that someone needs to buy or license an image. An innovation to achieve this has been to publish 'images of the week' on the main Te Papa Facebook page that the picture library shares with marketing and events.

Masters also uses Te Papa Picture Library's membership of the LinkedIn network as a relationship building tool. Masters adds her professional contacts so that 'they remember who we are and that they're not just that day to us, that we will add them to keep them with the Picture Library'. She also uses LinkedIn to share resources, to demonstrate to other users that picture library staff are 'upskilling'. LinkedIn groups, such as Digital Asset Management and Digital Marketing, facilitate discussion between members. This can include feedback, problem solving and recruitment.

Within the area of collections and research, social media is used as a tool to provide access and exposure to collections, and to promote and promulgate research carried out by Te Papa experts. Adrian Kingston, collections information manager in the Digital Assets and Development section, manages the @TePapaColOnline Twitter account. The idea behind creating the account 'was to expose Collections Online' and counteract the popular myth that everything is 'thrown in the basement'. Kingston tries to find 'interesting' objects in the collection to tweet in order to 'hook' people and make them click on the link. The @TePapaColOnline Twitter account is also used to foster collaborative partnerships with other institutions and cultural organisations, such as the National Library of New Zealand, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand and a number of Australian libraries, museums and galleries. One instance of this collaboration is the #collectionfishing hashtag. Each week somebody picks a theme and different cultural institutions participate by linking to items in their online collection and adding #collectionfishing to their tweet to enable other people to find it.[26] Kingston believes that this is more for members of the public than it is for the institutions involved, stating that 'the non-institutions can follow the #collectionfishing hashtag and see all of these institutions talking about, showing or exposing their collections'. The account has also been used to enhance collection information in a similar way to the earlier example of the Powerhouse Museum. Kingston had one user translate a postcard from French via Twitter. Kingston also blogs on the Te Papa blog to inform people about new features of Collections Online, addressing issues of digital literacy.

Leon Perrie, curator of botany, has been blogging on the Te Papa blog since October 2008. For him the blog is something that is 'increasingly about updates and notifications', whereas the Collections Online website is 'more of an authoritative voice, something of permanence, where we deliver information about things'. Perrie uses the blog to disseminate research, albeit in a more popular and accessible format. He feels that 'there's no point in doing stuff if you don't provide a way for people to access it'. He thinks that 'it's really important to inform people and the blog is simply another way of doing that'.

Te Papa created the role of senior concept developer, digital projects, within the Experience directorate, in recognition of the growing importance of digital media and the internet. By placing the position within Experience the Museum is indicating a shift in direction from just purely pushing out information to enhancing experience and engagement. Kate Woodall, formerly an exhibition project manager for Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) in the United Kingdom, is currently employed in the role. While working for HRP, Woodall was involved in developing viral games as part of an integrated marketing campaign surrounding the 500th anniversary of Henry VIII's accession in 2009. Two games, 'Henry VIII: Heads and hearts' and 'Henry VIII: Dressed to kill' (titled after the two key exhibitions mounted as part of the celebrations), were seeded across different social networking platforms. The aim was 'to get people to start their journey before they arrived within the physical space' and to subtly push the history behind it. They also served as effective marketing tools, promoting Historic Royal Palaces to a wide audience. For example, 'Henry VIII: Dressed to kill' received 2.1 million unique plays by mid December 2009, with more than 370,000 clicks through to the HRP website.[27]

At Te Papa, Woodall has been involved with the Unveiled and Oceania exhibitions. Social media was used within Unveiled to gather social history data and also to collect 'objects' for the exhibition itself. Visitors and the general public were invited to upload their own wedding and civil union photographs to an online gallery on Te Papa's website. These were then displayed on a digital screen within the exhibition. Te Papa's website stated that the aim was to 'provide a rich record of changes in New Zealand wedding style'.[28] Woodall was also part of a push to get wi-fi in Oceania to enable people who had smartphones to access additional information that fed into the different objects on display. This was supplied via QR codes. The content accessed via the QR codes was repurposed, rather than being created for the exhibition – the codes linked to the Tales from Te Papa videos that are hosted on Te Papa's website and YouTube. Woodall is not entirely satisfied with QR codes as an interpretive device, describing them as 'ugly'. She thinks that 'a lot of people don't understand what a QR code is, so if you're going to use a QR code you need to explain it … interpretation is meant to be self-explanatory'. You also need to have the app on your smart phone to be able to scan them. This could become less of an issue as the technology becomes more commonplace.

Sarah Morris, an interpreter at the museum, explained that there was a specific directive to use social media to engage with a youth audience for an exhibition in the community gallery called The Mixing Room: Stories from Young Refugees in New Zealand. The young people who collaborated in developing the exhibition created digital media, such as films and audio poems, which are displayed on three large multi-user touch tables within the space. This content is also available on YouTube and was rolled out, over a period of months, on the exhibition's blog. The exhibition also includes a large photo-mosaic installation fed out of Flickr, using photographs taken either of or by young people from refugee backgrounds. The exhibition is unusual in that there are no objects on display. Digital media was used in this case to fill a gap in Te Papa's collecting and also to substitute for objects that were simply too precious for people to lend. The shifting role of the museum in the 21st century from expert to facilitator is demonstrated by Morris's comment regarding the principles that guided the development of the exhibition:

We've tried to step back from being the experts, which we're not. None of us are refugees. In terms of owning the content and having authority over it, it's actually the young people that own that content, it's the young people that told us what to do with that content and how they wanted it displayed.

Morris also posts on the main Te Papa blog about her interest in social issues. She likes to promote and advocate topical events such as World Refugee Day or Race Relations Day. She feels that the Museum has some social responsibility in this area in terms of 'encouraging diversity and tolerance'.

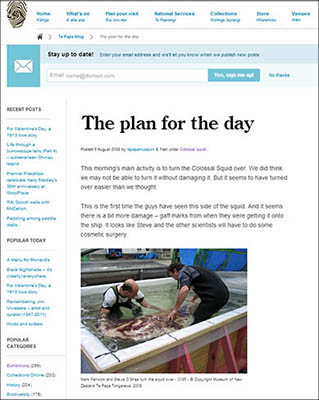

The Te Papa blog was initially set up as an addition to the Whales Tohorā exhibition so that the curator and interpreter could discuss some of the issues that hadn't made it into the exhibition. Lucy Hoffman, software development manager, describes the blog as being 'more around curators having their own voices and being able to talk to people and have research'. It is 'a slightly different model where rather than the single voice that comes through a centralised point, that's one that anybody can write on it'. In August 2008, it was used to 'liveblog' the dissection of the colossal squid, an event that took place at the Museum's Tory Street scientific research facility. The examination process was broadcast via the internet using webcams and the blog was used in addition to this, to post photographs and explain in more detail what was happening. The blog also enabled real-time discussion to occur between museum staff and the public.

The immense public interest and success of the blog and webcast led to the Colossal Squid exhibition, as well as associated merchandise and the Build a Squid game. Hoffman believes that 'getting things out there' on social media is a great way to sell a product. In her experience, the scarcity model, 'where people traditionally think if you make things available then it's no longer unique and valuable', doesn't apply online:

I think what the internet does is that it turns it on its head and says you can reach all these billions of people if you make stuff available and findable and you don't need very many of them to actually buy it.

Management, sustainability and evaluation

The research also revealed a great deal about the wider implications of the practice of social media across Te Papa. Staff identified a number of issues they have encountered in social media usage. One of these was shared accounts, which is where one social media account is jointly used by different departments who may have different, or even conflicting, aims and objectives. This caused problems for Kingston when he first trialled Flickr as a way of putting the Museum's out-of-copyright photographs online, 'to see what kind of impact we could get in terms of distribution, comments, that kind of thing'. The account was called 'Te Papa', but because of this general title other staff wanted to use it as well. This led to a confusing selection of content where, for example, digital images of collection items were viewed alongside photographs from Te Papa's 10th birthday celebrations. This 'really blurred the lines of what it was for and people didn't understand'.

On the other hand, sharing an account broadens your audience base. Masters stated that this is one of the main reasons why the Te Papa Picture Library is still under the main Te Papa Facebook account, because 'you're hitting a bigger audience'. Also, you could say that people who are interested in Te Papa 'might be interested in the Picture Library as a sub business'. She did warn that having too many people with administrative rights can cause a lot of posts and 'if someone sees too many posts they'll hide you because they're sick of you'.

The problem of how to deal with negative feedback was also raised in the interviews. Masters referred to an incident where someone on Twitter had accused the Picture Library of taking orders and payments but not delivering the product. Highlighting one of the dangers of individual social media accounts, the Picture Library are not Twitter users and had it not been for the marketing staff they would not have known about the complaint. Unfortunately, due to the limited amount of personal information provided on the site the Picture Library was unable to find out who the disgruntled client was in order to resolve the issue. Masters admitted that one of the downsides of social media is that 'you can get a positive message out there, but also negative messages that could be factually wrong can go at the same speed'. Her concern is that that person aired their grievance on Twitter before approaching the Museum.

Thoughts and feelings shared by members of the public on social media can be intensely personal and can deal with sensitive subject matter that could potentially place staff in difficult positions. Morris had an experience where one young refugee wrote a blog post about being gay and wanting to go to art school, but that he was under pressure from his family to study IT and go through with an arranged marriage. Morris didn't know how to respond and the move 'from interpreter to social worker' made her feel 'quite uncomfortable'. While some at the Museum were excited that the blog was being used to initiate these kinds of discussions, she felt that it was outside her job description.

When I conducted this research in late 2011, Te Papa had no formal internal best practice guidelines to assist staff in dealing with such situations, although this was something that Ward was working on with the manager of marketing and communications. Her advice, with regards to negative feedback, is 'to be careful about what you say to begin with … don't open yourself up to it'. If negative comments are posted it is sometimes best not to do anything at all, 'because you don't want to fuel the fire'. Taking the conversation offline is one way of preventing it from dominating your online presence and also demonstrates to those who are watching that the situation is being resolved. Masters also mentioned that it is possible to change settings on Facebook to control what the public can view and post on your timeline without having to take the entire page down.

Negative feedback is not something that organisations should be afraid of. Social media's immediacy and instant feedback can actually be a positive thing in that it allows the Museum to respond quickly to problems and resolve them before they become a major issue. Ward believes that 'it's good to know these things' so that you can 'nip it in the bud'. In Hoffman's experience social media is also quite self-moderating in that 'if someone's being outrageous to you, it's very likely that someone else will come back in and say, "Hey that's an unfair way of talking to them. You shouldn't do that"'. This is one of the six key principles of a concept espoused by marketing guru and social media proponent Collin Douma, known as 'radical trust'. The principles of radical trust are that you must believe that people:

- are best equipped to determine their own needs, and left to their own devices are best equipped to get those needs met.

- would rather be communicated with than spoken to.

- require freedom of expression, but often require guidelines to create expressions within.

- will self-regulate communities to the level guidelines suggest that the collective group they comprise will accept.

- will disconnect with a brand that silences them and will align with brands that give them a voice.

- are inherently good.[29]

This level of trust also extends to staff. When Hoffman first started at Te Papa all content had to pass through writers for vetting. As a result there was hardly anything in Collections Online. The decision was made to let staff self-publish:

We had to make a pragmatic decision and say, well, actually curators are pretty articulate and they’re all pretty highly educated and they are the experts in their field, so we’ll just trust that they can publish and that they won’t say anything stupid, and there’s been absolutely no problem with that.

This includes Kingston's twitter feed. The incentive to take advantage of this trust is diminished in that, as Hoffman puts it, 'it's all so discoverable and you can tell who's said something and at what exact time they said it, and probably if we really wanted we could find what computer they used'.

Both Masters and Woodall warned of the dangers of basing New Zealand projects on overseas examples. Masters considered using foursquare[30] as a treasure hunt tool, the idea being that users could 'check-in' at the Museum and be given clues to find a print or a voucher for a print. However, she decided against it because '[foursquare] really isn't taking off here. It's a States thing … I'm not sure we've got the population for it'. In relation to the use of mobile devices within exhibition spaces, Woodall is aware of the limitations imposed by the 'data issue' in New Zealand, where the fact that there is only one cable transporting internet traffic in and out of the country means that our cable charges are 'horrendous'. Further, many people who have smartphones still only text and phone, 'they don't actually know how to drive the rest of their phone', and smartphones in New Zealand are relatively expensive. Therefore, 'the stats that you have on smartphone usage that you get from the rest of the world don't correlate with what happens in New Zealand'. Woodall has found statistics on smartphone usage within New Zealand difficult to source. This is something that she has been working with Te Papa's visitor market research team to address.

The sustainability of exhibition related blogs was called into question by Morris who described them as 'kind of like little puppies' where 'they're really cute and everyone wants them and everyone wants to play with them, and then they grow into big dogs that you have to take for a walk and you have to feed … and then they're not so cute anymore'. When The Mixing Room blog was first set up there was a lot of activity for the first six months, with staff and the youth reference group of about ten people contributing content. Now 'nobody visits. It's been and it's gone ... the young people they've grown up … they're playing somewhere else in cyberspace. They don't want to play with a 43-year-old woman who works in the Museum'. Morris had hoped to create something that she could slowly step away from and that the young people would be motivated to keep generating, 'but that hasn't happened in reality'. Also, the nature of Morris's work is that it is project based and once an exhibition opens she is on to the next project. In the case of The Mixing Room she negotiated time set aside in her work plan to maintain the blog. It is not unusual for social media sites to experience fluctuations in popularity. Members of the OCLC (Online Computer Library Center) Social Metadata Working Group, Karen Smith-Yoshimura and Cyndi Shein found that 'it is very common for a page to receive a large number of visits and comments when it is first launched, or the public first becomes aware of it, and for views and comments to wane as the novelty of a site wears off'.[31]

User-generated content presents a challenge with regard to how it is to be managed in the long term. Woodall feels that 'it's all very well us going yeah give us your stuff and we use it perhaps online or, as is going to happen in Unveiled, they'll actually be shown in the space and that's lovely, but what happens to them once the exhibition finishes?' This is intangible heritage and is something that 'we as museums haven't got our heads around yet'. There are many things to consider, such as searchability and permission rights, and 'really everyone's going "Oh no that's too hard"'. As institutions like Te Papa are doing more and more of this kind of collecting, 'we're beginning to think actually we need to have more of a conscience about this, so this is a big area'.

As public relations experts Adrienne Fletcher and Moon J Lee have identified, social media requires time and commitment to implement effectively.[32] This was one of the downsides mentioned by Ward, that it 'does require you to be on all the time'. There is an obligation to respond to comments. Hoffman feels that 'if someone's honoured you enough to write something on your blog then you need to honour that back'.

Monitoring the usage of social media 'is unchartered territory and an emerging field of study' that museums are grappling with.[33] Te Papa staff use a number of different tools to judge the relative successes and failures of their online contributions. These include Google Analytics, Bitly, AddThis, Facebook Insights and YouTube Analytics. Te Papa only formally reports on website numbers, such as visits to Te Papa's website and Collections Online, as part of their Statement of Intent reporting. However, staff do still monitor things such as 'views', 'likes', 'shares' and 'retweets'. The more views, likes, shares or retweets a post has, the more successful it is considered to be. Ward also analyses 'not just what content does well, but what style and what time of day'. Te Papa staff track referrals from social media back to the Museum's website. These statistics enable them to assess whether users are actually clicking on the links. Kingston also tracks whether people are linking independently to Museum content, such as Collections Online and the Te Papa blog. He commented that 'we know that people ... are tweeting links to Collections Online, which is great because it means we don't have to, so we want to see that traffic as well'.

Interpreting this data presents challenges. Masters has been unable to exclude internal computers from the statistics, explaining 'I have a very sneaking suspicion it may have been my click throughs, me sorting the page out'. For the Te Papa blog, staff can only count the number of views, not the number of people (for example, one person could have viewed a single post multiple times). Factors such as public understanding are also harder to measure. Hoffman highlights the difficulties associated with assessing success based on numbers alone:

I think that that's not really the right measures. I think that just counting ... like we give out free newspapers. There are probably 50 people who just come through the door every day to get the free newspaper, so the numbers through the door, even that's not a great measure. What does that mean? Have we been successful as a cultural institution because we gave away ...? Maybe we should just stop doing exhibitions and just give stuff away. It'll get people through the door.

She was hoping that as part of a recently conducted 're-visioning' process they would be given more interesting success criteria. Defining success related to the number of likes on Facebook is also problematic. Both Ward and Masters admitted that the number of likes is only an indication of those who might see Te Papa's posts in their news feed. It does not mean that they are engaging or interacting with the Museum's content in any meaningful way. Ward explained:

You've got to remember ... here we've got about 7000 Facebook fans. That's 7000 people you could potentially reach, but one of them could be my mum who goes on Facebook once a month so she's probably not going to read your posts.

Overall, staff defined success as users engaging or interacting – viewing, clicking on links, sharing and commenting – with the Museum's content. However, a lack of active participation does not necessarily indicate failure. When Kingston was participating in collection fishing with the National Library and Te Ara, he found that 'people wouldn't necessarily be jumping in ... then every now and then you would see somebody tweet "love watching the fight between TePapaColOnline and NLNZ", so you know that they're actually watching'. He says that 'you learn after a while that it's okay if people aren't necessarily directly talking to you all the time'. Smith-Yoshimura and Shein have dubbed these users 'silent surfers', people who 'follow electronic communications with great interest on a variety of sites without ever responding to them'.[34] According to Kingston, 'you need to understand when you're tweeting that there's all sorts of barriers for why people aren't necessarily directly talking to you. It doesn't mean that your tweets aren't being heard and looked at'.

The future of social media at Te Papa

At the time this research was undertaken Te Papa was in the process of developing its digital strategy. Masters stated that 'we're at that point of we've done our experimenting, we now need to have a strategy in place'. She has observed the effect of directionless Facebook accounts, where 'you see the most boring Facebook pages sometimes of companies that have set it up because everyone else has one'. She feels that 'there has to be a reason behind it and what its purpose is'. This is in line with Russo, who asserts that 'to create sustained participation in social media spaces, museums will need to develop better understandings of the types of cultural exchanges they wish to elicit'.[35]

Woodall stressed that it is about using the right tool, that is, considering 'What are the stories that we're wanting to deliver?' and 'Who are the audiences?' In developing the Kahu Ora exhibition, which was about Māori weaving, social media was considered but ultimately rejected as not the right means for engaging with the intended audience. As Woodall explained, 'that's for quite a specialist audience and Māori weavers. It's not to say they don't use social media, but maybe our energies would be best served doing something else'. She sees her role as being 'to champion digital interpretation, but also to go "you're saying social media, but actually there's possibly a better way of doing it to get to the people that you want to get to using the stories that you want to use"'. She stated that while social media 'does offer a way to enable museums to get into co-creation [and] to get into a wider engagement' they need to be careful 'not to get totally seduced by it'.

Hoffman felt that the shift towards a more customer-focused model of engagement presented challenges to the way in which the Museum has historically operated. Where 'it used to be more about right, people want to engage with us they will come through the door and they'll buy a book – you come through the door for this thing and you buy a book for that thing and there's no crossover', today 'you've got different types of people who at different points in their lives, or even just different points in their day ... are interacting with us in the same day in a totally different way, wanting totally different stuff' and there is more immediacy about people's expectations. The notion of a general public that wants everything is part of the challenge. Also, social media 'is not a physical thing and it's not an authority thing, it's an opinion based thing ... and by its nature it's quite personal and museums haven't historically been very personal places'. Social media 'is about people connecting with people, not demographic lumps or stereotypes'.

One common theme to emerge from the interviews was that social media platforms are seen as more suited to an informal and personal approach. Ward felt that by tweeting something personally, 'you can target it better and you can create a wee angle'. She thought that 'people get a bit annoyed when it's just automatically done'. Both Masters and Kingston mentioned that they try to be 'humorous'. For Masters the idea was to 'capture a market that wasn't so serious about the work … and get some people to laugh and get that engagement'. Kingston's aim with @TePapaColOnline was that 'we didn't want to be this thing that people were afraid of'. He felt that trying to be overly authoritative on Twitter was out of place and that 'you'd get pretty quickly ignored if you were too official'. Hoffman also stated that 'copying material out of the brochure doesn't really make for very interesting or engaging content ... it's got to have more of a personal voice and maybe be from a particular person to a group'.

In a recent study investigating how American museums are currently using social media all museum practitioners interviewed agreed that 'social media is here to stay and important for museums, especially as a means to promote visitor engagement'.[36] For Kingston, 'it's about being in the digital world and that might either be in person or through the collections, or by making knowledge available that people use'. He gave the example of someone doing their tattoo research and seeing something they liked on the Museum's website. They may not have had an interaction with the Museum that they will remember, 'but we still were part of that person's life'. Whether the Museum is happy with it at that layer he doesn't know, 'but we need to be part of that and if we're not part of that person's tattoo research ... they don't know we exist'. He thinks that 'there're a huge amount of competition out there' and that Te Papa needs to do more with other New Zealand institutions, such as the National Library of New Zealand and Archives New Zealand, in order to 'link up a lot more and share that burden'.

Te Papa in 2014

In the past two years Te Papa has undergone a major restructure and is continuing to develop its digital strategy and implement changes in this area. For instance, there is now a staff member who works solely in social media marketing and there is a practice leader digital position that will hopefully be filled in the 2014–15 financial year. Woodall is now the manager of audience engagement and her team is moving into using social media as a way to facilitate an active dialogue with visitors via Twitter and the blog. They are organising a Twitter commentary for their Treaty Debates series in February 2014 – a first for Te Papa.[37]

Kingston continues to make use of social media tools. He still uses Tweetdeck for monitoring general Twitter activity, AddThis for seeing how people are sharing Collections Online links and Google Analytics for tracking referrals.[38] One recent event was a 'Tweet-off' competition between the Collections Online account and the National Library of New Zealand's twitter account, @NLNZ, initiated by journalist Megan Lane, @laneasinlois, when she was running the national @PeopleofNZ account.[39]

According to its 2012–13 annual report, 'Te Papa's online experience is an increasingly important way of facilitating public engagement with the museum collections, sharing information with a variety of communities, and fostering debate'.[40] It states that 'online visitation to the website has been steadily increasing as more information is made available and more people use the Internet as a research tool' and mentions that 'Te Papa also engages with online communities via our blog, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube channels'.[41] Social media statistics are not included and, with regards to digital access to collections, performance is still measured by number of visits to Te Papa's website and Collections Online.

Conclusion

This research has showed that social media is being used by staff at Te Papa in a number of different ways, including but not limited to marketing the commercial side of the business. Social media has proved useful in providing greater access to collections and research, breaking down barriers and overcoming the 'threshold of fear' described by Nina Simon in her blog Museum 2.0.[42] It is also useful for enhancing visitor experience and engagement, and involving the public in exhibitions.

Staff mentioned a number of ideas for things that they would like to try in the future. These included having a space to display artworks as chosen by the Museum's Facebook fans and 'Guerilla app' tours (where members of the public create their own tours of exhibition spaces and then share them online). One interviewee felt that the Museum is not currently doing enough to engage with a teen audience. They thought that having 'that younger looking faces' going through an exhibition and making their own videos, similar to curator's talks, would be a good idea. Kingston is also planning to add the ability to comment on collection items to Collections Online. This would then become part of the documentation history of the object.

As I noted in the introduction, there are few case studies within museum studies that examine social media use by museums at an institutional level. There is also an absence of research undertaken around current practice in New Zealand. This article has attempted to address this gap in the literature. The topic is becoming increasingly important as more and more museums are investing in positions dedicated to social media.[43] The 'social' turn that has irreversibly changed the current media landscape 'will likely only grow in significance for museums'.[44] There is therefore need for more research to guide professionals in their work.

This article has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes

1 Lynda Kelly, 'Learning in the 21st century museum', paper presented at the LEM conference, Tampere, Finland, 12 October 2011, http://australianmuseum.net.au/document/Learning-in-the-21st-Century-Museum/, viewed 29 April 2012, p.1.

2 Alison Griffiths, 'Media technology and museum display: A century of accommodation and conflict', in David Thorburn & Henry Jenkins (eds), Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2003, pp. 375–89; Michelle Henning, 'New media' in Sharon Macdonald (ed.), A Companion to Museum Studies, Blackwell, Oxford, 2006, pp. 302–22; Ross Parry (ed.), Museums in a Digital Age, Routledge, London and New York, 2010.

3 David Mason & Conal McCarthy, 'Museums and the culture of new media: An empirical model of New Zealand museum websites', Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 23, no. 1, 2008, 63–80.

4 Juan Francisco Salazar, '"Mymuseum": Social media and the engagement of the environmental citizen', in Fiona Cameron & Linda Kelly (eds), Hot Topics, Public Culture, Museums, Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2010, p. 265.

5 Angelina Russo, Jerry Watkins, Lynda Kelly & Sebastian Chan, 'How will social media affect museum communication?', in Proceedings Nordic Digital Excellence in Museums (NODEM), Oslo, Norway, 2006, http://eprints.qut.edu.au/6067/1/6067_1.pdf, viewed 14 June 2013, p. 2.

6 ibid.

7 ibid.

8 ibid.

9 Powerhouse Museum, www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=248651&search=inclinometer&images=&c=&s, viewed 9 January 2014.

10 Nancy Proctor, 'Museum as platform, curator as champion, in the age of social media', Curator, vol. 53, no. 1, 35–43 (p.37).

11 Angelina Russo, Jerry Watkins & Susan Groundwater-Smith, 'Impact of social media on iformal learning in museums', Educational Media International, vol. 46, no. 2, 153–66, (p. 153).

12 Allegra Burnette & Victoria Lichtendorf, 'Museums connecting with teens online', in Herminia Din & Phyllis Hecht (eds), The Digital Museum: A Think Guide, American Association of Museums, Washington, DC, 2007, p. 92.

13 ibid.

14 Matthew MacArthur, 'Can museums allow online users to become participants?', in Din & Hecht (eds), The Digital Museum, p. 61.

15 ibid.

16 ibid., p. 62.

17 Lynda Kelly, 'The impact of social media on museum practice', paper presented at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 20 October 2009, http://australianmuseum.net.au/document/The-Impact-of-Social-Media-on-Museum-Practice, viewed 29 April 2012, pp. 9–10.

18 ibid., p. 10.

19 Amelia Wong, 'Ethical issues of social media in museums: A case study', Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 26, no. 2, 2011, 97–112 (p. 104).

20 ibid. (p.105).

21 ibid.

22 ibid.

23 For a full account of my methodology and results, see Georgina Fell, Going social: A case study of the use of social media technologies by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Masters thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, 2012, http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/2555.

24 Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Act 1992, Section 4, www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1992/0019/latest/DLM260204.html, viewed 11 January 2014.

25 ibid., Section 7.

26 Public Record Office Victoria, 'Just digitise it', http://prov.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Just-Digitise-It.pdf, viewed 18 February 2014.

27 'Viral games', www.hrp.org.uk/Revolutionawards/Bestintegratedmarketingcampaign/Henry500/Viralgames, viewed 2 February 2014.

28 'New Zealand wedding photo gallery', http://sites.tepapa.govt.nz/weddingphotos/, viewed 29 April 29 2012.

29 Collin Douma, 'What is Radical Trust?', www.radicaltrust.ca/about/, viewed 16 June 2013.

30 Foursquare is a location-based social networking site designed for mobile devices such as smartphones. Users 'check-in' at certain locations based on the GPS tracking built into their device and receive points for the number of times they check-in. The user who checks in the most often to a venue becomes the 'mayor' and users regularly vie for 'mayorships'.

31 Karen Smith-Yoshimura & Cyndi Shein, Social Metadata for Libraries, Archives and Museums Part 1: Site Reviews, OCLC Research, Ohio, 2011, p. 65.

32 Adrienne Fletcher & Moon J Lee, 'Current social media uses and evaluations in American museums', Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 27, no. 5, 2012, 505–21, (pp. 505–506, 508).

33 Smith-Yoshimura & Shein, Social Metadata, p. 65.

34 ibid., p. 66.

35 Angelina Russo, 'Transformations in cultural communication: Social media, cultural exchange, and creative connections', Curator, vol. 54, no. 3, 2011, 327–346 (p. 327).

36 Fletcher & Lee, Current social media uses (p. 513).

37 Email to author, 23 January 2014; www.tepapa.govt.nz/WhatsOn/allevents/Pages/TreatyDebatesWaterIsOurBusiness.asp.

38 Email to author, 22 January 2014.

39 'Tweet-off: Most choicest collection', http://storify.com/laneasinlois/tweet-off-most-choicest-collection, viewed 1 February 2014.

40 Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Pūrongo ā Tau Annual Report 2012/13, http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/SiteCollectionDocuments/AboutTePapa/LegislationAccountability/1-821150-Te_Papa_Annual_Report_2012-13.pdf, viewed 2 February 2014, p. 19.

41 ibid.

42 Nina Simon, 'Come on in and make yourself comfortable', http://museumtwo.blogspot.co.nz/2012/02/come-on-in-and-make-yourself.html, viewed 18 June 2013.

43 Wong, 'Ethical issues' (p. 97).

44 ibid. (p. 98).