From Parisian workshop to museum repository

Introduction

The year 2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the manufacture of the National Museum of Australia’s oldest motor car. Purchased for the collection in 1982 by an interim Museum council and accessioned long before the establishment of the present galleries at Acton Peninsula, the 1913 Delaunay Belleville also reflects the institution’s early endeavours in selecting and acquiring material for the National Historical Collection. Despite evident budgetary restrictions of the time, Museum staff assiduously filed a wealth of supporting documents including historical photographs and detailed transcripts of interviews with former owners. In itself, this car’s survival is a testament to the dedication of these successive owners, who by their actions saved it from dereliction or the scrapyard. Although seldom seen by the public in the 30 years since accessioning, the car’s inclusion in the Museum’s Glorious Days: Australia 1913 exhibition has prompted a consolidated review of both the material culture and archival evidence.

Several prominent Australian historians, including Graeme Davison, Margaret Simpson and John Knott, have in recent years given attention to the transformative role of the motor car in Australian social and cultural history over the 20th century.[1] It has been well established that Australians embraced the coming of the motor car with alacrity, perhaps due to greater instances of isolated wealth, or the value of such a machine in vanquishing geographical distance across the continent. As the repository of a complex history spanning the decades (and distance) between France’s Belle Époque and contemporary Australia, the Delaunay Belleville is a powerful museum object that enhances narratives encompassing the twists and turns of the Australian motoring past. Significantly, the unusually detailed level of provenance and the physicality of the vehicle itself also allow the rare opportunity of uncovering an unexplored layer of social history: the shadowy domain of the car collector.

Although detailed analyses of this phenomenon remain incomplete, Australian enthusiasm for car ownership is clearly identifiable by the beginning of the twentieth century. This later transformed into a recreational pursuit after the end of the Second World War, sometimes involving a project of ‘restoration’ reflective of individual perceptions of the material past. The collection and display of historic cars continued to grow in scope and popularity in Australia, eventually reaching its peak during the 1970s. Today, this interest is still conducted through many forums, such as small amateur museums, national collecting institutions, and gatherings of enthusiasts at shows and rallies. It is clear therefore that those who collect and restore cars form a significant group, though notably divided along issues of aesthetics, functionality and historical authenticity. This overlap between motoring and social history can usefully be explored in conjunction with the focus on material culture characteristic of the new museology.[2]

Drawing on these elements, this article will retrace the social history of the Museum’s Delaunay Belleville from its manufacture in a Parisian workshop in 1913 to its current incarnation as a museum object. It will contextualise the emergence of the car collector in Australia by examining the involvement of five owners of the Delaunay Belleville, and the ways in which each acquired, used and adapted this significant piece of the material past in a reflection of their contemporary interests. In doing so, this article will offer a new perspective on the way the motoring landscape changed over the twentieth century, and a deeper understanding of the popularity of collecting and adapting historic cars in Australia.

photograph by Jason McCarthy, National Museum of Australia

The very latest in French fashion of 1913

It is not immediately apparent, even to the initiated, that the Delaunay Belleville’s current outward appearance results from its reconstruction in the late 1960s. The Paris-manufactured chassis (model IA4) and engine block (number 5243V) together comprise most of the parts of the vehicle that can be firmly dated to 1913.[3] Nonetheless, the Delaunay Belleville retains the potential to reveal much information on pre-First World War engineering practices. All elements of the four-cylinder side valve engine record the precision bespoke engineering characteristic of this manufacturer. The 3.75-litre capacity engine block incorporates a number of advanced mechanical features of the time, including a full pressure-lubricated crank and camshafts, a water-cooling system, and tubular connecting rods.[4] The standard ‘H’ gearbox with cone clutch allowed for good performance, using four forward gears and one reverse. Rated at a modest 17–20 horsepower, this was one of Delaunay Belleville’s smaller motor vehicles but it nonetheless demonstrated an imposing 9-foot (2.75-metre) wheelbase. Evidence of the original silent starter feature remains in situ.

The car also speaks eloquently to the Australian desire for imported technologies. After the invention of the internal combustion engine in Germany at the end of the 19th century, much of the initial popularity of the motor car can be attributed to French manufacturers during the early years of the twentieth century.[5] Motoring historian Shane Birney has noted that although many enterprising Australians made serious attempts to establish a home-grown car manufacturing industry in the years following Federation, many wealthy patrons looked almost solely to Europe, and especially France, for the supply of luxury vehicles.[6]

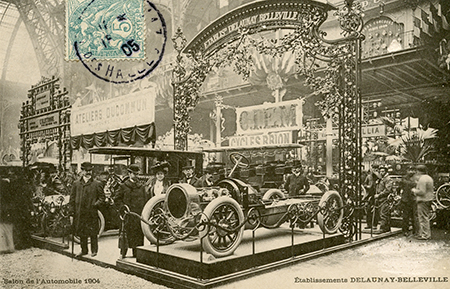

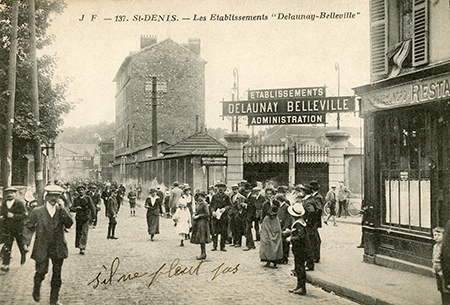

Delaunay Belleville was first established as a boiler manufacturer operating at St Denis in northern Paris during the 1860s. By the turn of the century, the company joined the ranks of Parisian industrial manufacturers who responded to the increasing popularity of the motor car by turning their trade to producing automotive engines and chassis.[7] Across industrial Europe, progressive manufacturers adapted elements of the innovative practices and centralised workmanship being pioneered by American magnates. Despite catering to a luxury market and producing relatively few vehicles, Delaunay Belleville’s success was assured when several early models were exhibited in 1904 at the Salon de Paris, an influential annual showcase of arts and fashion. During this period, broadly identifiable as the final stages of the Belle Époque, the world looked to France for all that was fashionable in society, technology and culture. Decisively terminated by the advent of war in 1914, the era was characterised by a vibrant sense of optimism, the vigorous development of scientific and technological endeavours, and an overriding illusion of peace and prosperity.

National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

During these gilded years, Delaunay Belleville emerged as one of the marques of choice for the ‘very rich and the very conservative’, and counted ambassadors, heads of state and most notably the Russian Tsar, Nicholas II, amongst its clients.[8] Proclaimed ‘the most fashionable car in London, Paris and New York’, such an acquisition was the ultimate affirmation of social standing.[9] A later author envisioned the typical clientele to be: ‘lovely ladies tripping daintily down from a stately Parisian theatre, or from a risqué club in Clichy … climbing coquettishly aboard with a tantalizing rustle of silks and satins, to flounce down amid the ample upholstery and press the driver’s telegraph button with a lace gloved forefinger’.[10] Although this car was not one of Delaunay Belleville’s most expensive or luxurious models, it was nonetheless an important signifier of wealth and good taste. During the year that its chassis and engine block were constructed at St Denis, the Delaunay Belleville marque had undeniably reached the zenith of its popularity.

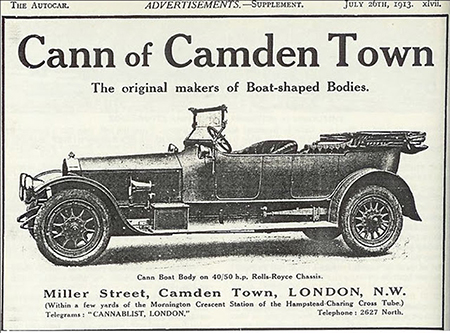

At this time, motor cars were assembled in two distinct stages. The completed chassis was shipped to England, where the car’s elegant body was constructed separately by coachbuilders Cann & Co. of London’s Camden Town, at some point between late 1913 and early 1914.[11] Although the details of the commission remain unknown, this collaborative endeavour reflects the diplomatic context of the early 20th century, when links between France and England were strengthened in the wake of the 1904 entente cordiale and the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition. Like their Parisian counterparts, English coachbuilders had modified their trade from the manufacture of horsedrawn vehicles in response to the motor car boom. English firms enjoyed a high international reputation, and placed as they were at the centre of Imperial trade routes, were able to provide high-quality vehicles to vendors across the world. Each vehicle was painstakingly designed and individually fabricated over a period of months, and optional additions pushed the prices into hundreds of pounds.[12] Delaunay Belleville motor cars retailed in Europe for about £800–£900 – a figure many times beyond the means of all but the most wealthy.[13] Although still for many Australians an aspirational possession, Ford’s popular ‘Model T’ dominated the affordable end of the market with its price tag of £215.[14]

Advertisements run by Dalgety & Co., the agency responsible for importing the car into Australia, suggest that batches of Cann & Co. vehicles were specifically designated to be exported for an Australian clientele. Despite the marque’s urban sophistication, Dalgety’s advertisements extolled Delaunay Belleville as the ‘ideal car for Australia’. These were, they claimed, ‘quiet running, most comfortable, extremely reliable [and] built for colonial conditions with an extra clearance from the ground, so that they may run on the worst of roads’.[15] Even if roads were non-existent, Dalgety assured buyers that the cars would ‘forge their way through mud, slush or sand without effort, and never falter at the steepest hills’.[16] Despite these claims, Edwardian cars were not typically reliable. This Delaunay Belleville’s racy torpedo body was especially strengthened, the suspension system stiffened and the paintwork finished in a light colour, probably a pale grey, with fine black pin-striping on the long curved mudguards.[17]

Autocar, 26 July 1913, p. 16

Controlling Imperial trade

Long before this car was shipped to Sydney, Dalgety & Co. had firmly instituted itself as one of the foremost pastoralist agencies servicing the needs of rural Australia. The well-established nature of old Imperial trade routes allowed the brokers to supply Australian graziers and other wealthy patrons with almost unlimited equipment and supplies, and control the export of domestic goods including gold and wool. Frederick Dalgety (1817–1894), an enterprising financier who developed large-scale broking, marketing, and shipping facilities for pastoralists and other rural producers, established the company in the 1840s. Dalgety’s biographer, RM Hartnell, identifies him as ‘one of the first merchants to see clearly the potentiality and needs of the squatters, and to exploit the mercantile and financial resources of Britain for the growing requirements of the Australian economy’.[18] By the 1880s, Dalgety had offices in London, Melbourne, Geelong, Launceston, Dunedin, Christchurch, and Sydney.[19]

From their powerful position in Australian pastoralist society, the company was quick to seize on the opportunity offered by the European motor car industry. In about 1909, it began importing Delaunay Belleville cars, vigorously promoting the marque in the pages of the Australian Motorist and the Sydney Morning Herald.[20] In April 1912, an attractive example was paraded for all to admire in one of the first motor shows to be held at Sydney Showground.[21] The promotional offensive intensified further the following June, when JJ Mann, an agent from Delaunay Belleville’s works in St Denis, visited Sydney especially to ‘meet owners and prospective owners’.[22] It seems inevitable that wealthy Australians interested in new motor car technologies should fall under the spell of this promotional onslaught.

Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, Dalgety: The Romance of a Business, H Melland, London, 1984, p. 70

A privileged pastime

The nationwide enthusiasm that motor cars generated in the decade before the First World War is perhaps explained by the functional solution they offered in traversing large areas of land and the distances between relatively isolated towns. Many early 20th-century Australians undertook exploratory or recreational journeys across the continent, and contemporary media charted the achievements of record-breaking drivers such as Francis Birtles, Harry Dutton and HH Murray Aunger. By 1913, the activities of the owners of some 13,192 motor cars registered in New South Wales were supported by a handful of fledgling motoring car clubs who organised a plethora of social meets, recreational tours, and rallies.[23] For those who could afford a car, their personal mobility was transformed beyond all imagining.

Although Delaunay Belleville cars were especially favoured by French drivers for racing, the rarity of this car in an urban Australian context would have instantly set it apart as a display of capital and consumerism.[24] As in France, the marque was favoured by only the most prominent of clients. For example, a Delaunay Belleville conveyed the Governor-General’s wife, Lady Denman, to Canberra’s naming ceremony in 1913.[25] Department store heir and grazier Anthony Hordern was also an owner.[26] Holding prominent positions in society, these wealthy individuals had much in common with this Delaunay Belleville’s first owner; one James Bunbury Nott Osborne (1878–1934), a grazier and stockbreeder based at Bowylie, an 1890s homestead on the outskirts of Gundaroo in New South Wales.[27]

Osborne was the fourth son of Pat Hill Osborne, a wealthy Irish pastoralist and horse breeder who ran sheep across a string of outstations across New South Wales.[28] Educated at prestigious Rugby School in England, he served as a member of the 1st Australian Horse during the Boer War in South Africa between 1899 and 1902, before returning to live at Bowylie with his wife Maud (nee Jeffries), an American actress.[29] As a prosperous, educated and well-travelled young man, Osborne is typical of the generation who embraced the practicalities of the motor car with the greatest enthusiasm. Described as ‘keenly interested in sport’, his competitive edge appears to have extended to automotive technology.[30] In about 1907, he became the first in the region to own a motor car, a luxurious Minerva. Driving this Belgian import, Osborne established what was then the fastest travel time between Gunning and Gundaroo (42 minutes).[31]

Brian Dunn & Peter Blundell, The Boys in Green: A Centenary History of the 1st Australian Horse, Clarion Editions, Binalong, NSW, 1997, p. 13

The arrival of new motoring technologies would have been a novel prospect for the Gundaroo region. In one case, a local boy was ‘so terrified that he popped behind a briar bush’ after hearing the clattering approach of a motor car at nearby Sutton.[32] This clamour could have more serious consequences, often distressing the livestock that was a more familiar feature of most urban and rural roads. In 1909, Osborne himself was ‘cut about the face and bruised’ when his motor car collided with a horsedrawn cart after the frightened animal shied.[33] His second car, a less-than-functional French De Dion, held no such terrors for the community. Local historian Errol Lea-Scarlett records a humorous occasion when it broke down on Gundaroo’s main street and refused to move.[34]

Yet motor cars were undoubtedly useful. The capricious De Dion was abruptly replaced in 1912 with a ‘particularly fine’ American car, which was to famously save a labourer’s life in a near-fatal accident at Bowylie the following year. After the young man accidentally shot himself while hunting for rabbits, Osborne reportedly ‘at once kindly had his motor car and his driver out, and sent the young fellow into the Yass hospital’.[35] This was something of an isolated incident – in contrast, after the car was disposed of the following year, its new owner narrowly escaped death when the front axle broke during a steep descent.[36] Despite Osborne’s evident appetite for a rapid succession of new technologies, the delivery of this ‘very fine’ Delaunay Belleville in 1914 was considered an event of such magnitude that it appeared in an article in the local Queanbeyan Age newspaper.[37]

Given that motoring was a pursuit reserved for the privileged, Osborne’s new car most likely functioned both as a display of status and as a form of recreation. Photographic evidence suggests the car may have been used to seek out distant picnic spots for gatherings of family and friends. A contemporary English motorist described the experience as providing ‘ample sources of interest, amounting sometimes to a gentle and healthy excitement with complete rest and absence of fatigue from muscular exertion’.[38] Although Osborne was himself a skilled driver, his car was likely driven by a chauffeur, a new vocation that paralleled the rise of the motor car. After all, popular French racing driver Fernand Charron had decreed ‘no owner ever drives his Delaunay – it just isn’t done’.[39] Lacking service garages and petrol bowsers, both owner and driver would have had mechanical knowledge and carried their own supplies of gasoline in unwieldy tins.[40]

photograph courtesy Bedford Jeffries Osborne

Fall from grace

The final chapter of Osborne’s ownership records the Delaunay Belleville’s decline in his estimation. During the pre-war era, motor car technology developed at an extraordinary rate, and Osborne had the means and inclination to update his car models on a regular basis. By about 1920, the Delaunay Belleville had been transferred to its second owner, William Sibley, Bowylie’s estate manager. Little is known about this period of use, although some years later, the Sibleys reportedly used the Delaunay Belleville to attend the opening of the Australian Parliament in Canberra on 9 May 1927.[41] The large number of cars present at this event reflects the increasingly prominent place they occupied in everyday life. As historian Kimberley Webber has explained, cars remained ‘almost Depression-proof’, with only a marginal drop in registrations in the late 1920s, followed by a steady rise into the late 1930s.[42] The Sibleys’ Delaunay Belleville was no exception, and remained on the road for a notably long time, until at least 1941. It may be that the family acquired another car, or gave up driving during the war years when petrol was scarce.

National Library of Australia vn4226763

Australian attitudes towards cars changed most dramatically in the decade following the Second World War. The development of so-called ‘people’s cars’, burgeoning Australian manufacturing industries, and the reshaping of the urban landscape democratised car ownership, and ensured their ubiquitous presence. Such accessibility was aided by mass-production and the glamour and rivalries of motor sports, which attracted diverse audiences. As the material culture of the pre-war era decayed and disappeared from everyday consciousness, coach-built cars became a rarity on Australia’s roads. Nonetheless, some Australians still looked to these symbols of a more peaceful era, perhaps in an attempt to rediscover the familiar within a vastly changed world. This theme resonates throughout the work of cultural commentator David Lowenthal, who notes, ‘the less integral the role of the past in our lives, the more imperative the urge to preserve its relics’.[43] In many ways embodying this particularly mid-20th-century preoccupation, the remains of the Delaunay Belleville were to undergo an extraordinary transformation.

Rescued from decay

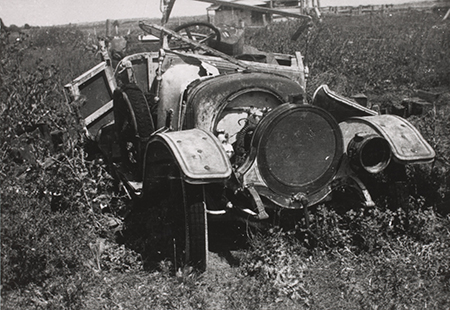

Five-year-old Robert Beer of Queanbeyan, New South Wales, first set eyes on the Delaunay Belleville, parked under a tree in Gundaroo. It was to make a lasting impression on him.[44] Self-described as ‘a car nut ever since I was zero years old’, Beer was familiar with the region as his father was employed as the property manager at nearby Michelago station.[45] By 1955, aged 18 and with a small amount of money to spend, he revisited Gundaroo in search of the car. He found it where the Sibleys had abandoned it, in a creek bed under the bridge.[46] After making contact with the family, Beer swiftly became the car’s third owner for the price of £35. Despite recalling his friends’ derision of ‘old garbage like that’, Beer described it as ‘the first motor car of any significance in the Gundaroo area’.[47] ‘I love the thing’, he said, ‘and I’ve always considered it to be my motorcar’.[48] This reference to a shared past demonstrates the importance of localised social-historical narratives in the construction of Australian identity.

During his ownership of the Delaunay Belleville, Beer proved himself to be a collector specifically focused on the preservation, or ‘saving’, of historic motor cars. Although it is unknown whether Beer intended to actively restore the dilapidated and rusted car, his primary motivation was to preserve a tangible reminder of the localised past. However, Beer married and left Queanbeyan within the year. The Delaunay Belleville was sold to a private car collector, Murdoch MacDonald of Canberra, in 1956.[49] Although his period of ownership was fleeting, Beer’s association with the Delaunay Belleville precisely marks a moment in post-war social history when motor cars underwent a discernible transition. In a changed world, and far from simply embodying the redundant past, historic cars now attracted attention as collectibles replete with nostalgic power and the potential to reflect aspects of their owners’ identities.

photograph by Robert Beer

Revival

The desire to become more closely reacquainted with the motoring past was also an important theme for the Delaunay Belleville’s fourth owner, George Green (1908–1982) of Campbelltown, New South Wales. As a young man, Green had travelled through regional New South Wales and Victoria with his father, a wool and sheepskin merchant operating under TW Green & Co, which allowed him ‘more opportunities than most to observe Australia’s changing motoring scene’.[50] As growing numbers of technologically sophisticated cars on Australia’s roads transformed social and urban development, the post-war era also witnessed a number of important changes in the collector’s market. These included the development of a formal and nationally acknowledged classification system for older cars (using terms such as ‘vintage’ and ‘veteran’), and the establishment of specialist groups to support the growing popularity of collecting and restoration. The Veteran Car Club of Australia (NSW), for example, was established in 1954 to promote the preservation and use of rare vehicles, and to provide social activities for its members.[51] Green attended the club’s first annual Blue Mountains Rally in 1956, and ‘enjoyed the event so much that he set out to start his own collection’.[52]

Within two years, Green purchased the Delaunay Belleville from Murdoch MacDonald. The motor car was in much the same state of conservation as when it was recovered from the Gundaroo creek bed. This purchase was not considered an investment in the way it would be today; non-functional motor cars were perceived as having ‘little more than nuisance value’ and many in Green’s collection were either ‘given or sold very cheaply’.[53] Although the collecting of cars was certainly a niche market, the prices did not remain low beyond the end of the 1950s, and prominent private collectors such as George Gilltrap, Arthur Parker and James Flood became renowned within their fields. Interest in collecting cars correlates directly with a burgeoning popular appetite for the everyday elements of the past, which is also discerned through the advent of ‘living history’ museums, historical re-enactment, family history research and ‘antiques’ shops which have emerged during the later decades of the twentieth century.[54]

It may be that collectors of cars especially sought the vestiges of the motoring past as an antidote to a growing culture of planned obsolescence. David Lowenthal has explored this reaction to unfamiliar environs, remarking that ‘nothing so quickens preservation sympathies as the fear of imminent extinction.’[55] Clubs of amateur enthusiasts sprang up across the country, including the influential Council of Motor Clubs NSW, founded in 1963.[56] Perhaps the largest and most active club was the Vintage Sports Car Club of Australia, in which Green played a prominent part. The establishment of the institution now known as the National Motor Museum at Birdwood Mill, South Australia, in 1965 also reflects the growing national institutional regard for motoring material culture and history.[57] Car ownership also came with expectations of performance and functionality, or as Green stated, vehicles should ‘be capable of giving a good account of themselves in a vintage rally’.[58] The visceral experience of motoring is one often cited in cultural narratives examining the presence of cars in everyday life.[59] In particular, this statement highlights the critical distinction between the collection of motor cars compared to other types of material culture, which is the unparalleled opportunity they offer to imaginatively re-enter the past.

Recreating the veteran look

In order to achieve the desired functionality, the Delaunay Belleville required the integration of entirely new parts, and Green and several associates embarked on a full-scale restoration project in 1968. The team shared a particular perception of how a French vehicle from the pre-First World War era should look, and how a car of that era should function. Although all were skilled tradesmen, historical accuracy and the preservation of the original fabric were not primary considerations. As a contemporary surmised, ‘[Green’s] main passion was to get them going, not to have them immaculate, not necessarily to get them totally original but to get them on the road’.[60] Over two years, the engine was fully reconditioned, and the interior upholstery replaced.[61] In contrast to the original low-slung torpedo body, a dissimilar replacement body was fitted slightly awkwardly over the chassis.[62] Finally, a coat of yellow paint gave the car a cheerful appearance quite unlike the original understated grey. As intended, the Delaunay Belleville’s first outing was the 1970 Sydney to Melbourne International Rally, then one of the most important events in the car collector’s calender.[63]

By the early 1970s, Green’s collection had grown to some 100 cars, prompting the establishment of Green’s Motorcade Park Museum at Leppington, New South Wales, in 1974.[64] The site was effectively a large leisure park with walking trails, a cafe, a pond with wildlife, and a picnic area. The exhibits featured a large hangar containing a cavalcade of motor cars, a folk-life village, recreated late 19th-century shops, a ‘Merchant’s building’ complete with coaches in the style of Cobb & Co, and a 1930s garage.[65] The Delaunay Belleville was employed in driving tours around the museum site, where it conveyed ‘thousands’ of visitors over the years.[66] As Green explained, ‘usually you will find one or more veteran cars roaming the grounds, giving visitors the opportunity to savour motoring as their parents and grandparents once knew it’.[67] Many aspects of Green’s museum are consistent with the widespread growth and approach of so-called ‘living history’ museums during the 1970s. As historian Anne-Marie Condé has discussed, institutions such as Old Sydney Town in New South Wales and Sovereign Hill in Victoria presented historical material culture and recreated practices for an audience intent on an experience outside of their own frame of cultural reference.[68]

Ray Sanderson

Frank Maguire, Veteran & Vintage Cars in Australia, Rigby, Adelaide, 1977, p. 62.

Joining the National Historical Collection

The sale of the Green’s collection after his death in 1982 was a catalyst. It came at a time when several large private collections of motor cars were dispersed, such as the famed collections of Arthur Parker and James Flood. Staff at the Museum of Australia (then in its infancy, and later to become the National Museum) watched in consternation as collections were dispersed, sometimes overseas. Critically, the wealth of knowledge and provenance acquired by well-known car collectors was also lost. When Green’s extensive auction catalogue became available in October 1982, several groups applied pressure to the Minister for Home Affairs and Environment, the Hon. Tom McVeigh, to ‘save’ the collection. Ian Irwin, Secretary of the Veteran Car Club of Australia, urged readers of the Canberra Times that ‘every thinking Australian should be concerned at the possible risk of some of these items going overseas’.[69] Rumours of supposed ‘French interests’ at the auction prompted cultural institutions, including the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney and the Museum of Australia, to lend their weight to the argument.[70]

Although Museum of Australia director, Alex Dix ,was anxious to purchase the Delaunay Belleville for the Museum’s collections, there were no funds to do so.[71] Dix was forced to concede that ‘we have nowhere near sufficient funds available … these vehicles could well be exported and probably lost to us forever.’[72] Museum staff identified this car’s provenance as being of particular relevance and the necessary funds were found in the budget to allow them to bid nonetheless. The institution became the Delaunay Belleville’s fifth and final owner at a cost of $24,000 – all of that year’s acquisitions budget and more. Other cars in the collection were purchased by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences and the motor museum at Birdwood Mill in South Australia.

National Museum of Australia

The Delaunay Belleville’s provenance contains an interesting legislative postscript. In 1982, the likelihood of export at the hands of shadowy ‘French interests’ was more than a perceived concern. Seven years earlier, the 1975 Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (most commonly known as the Pigott Report) had first highlighted the unregulated export of particular items of Australia’s cultural heritage.[73] The legislative furore surrounding the sale of Green’s collection ultimately succeeded in permanently altering the export freedom for historic vehicles. In 1986, the terms of the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act rendered the export of historically significant motor vehicles illegal.[74] By 1989, Australia announced that it would become a party to the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.[75]

Conclusion

Having now reached its centenary, the National Museum of Australia’s Delaunay Belleville has undergone a marked transformation since its manufacture in 1913. An analysis of the material culture and previously unexplored historical records has lent insight into a rich and complex history spanning the 20th century from Belle Époque Paris to contemporary Australia. The use of an object-centred analysis, and the turn to social history characteristic of the new museology, allow for the emergence of previously unexplored stories of Australia’s motoring past and, perhaps most compellingly, the little-explored history of Australian historic car collectors and owners. Drawing on material and archival records, this article has discussed the different attitudes of five owners of the Delaunay Belleville towards its aesthetics, functionality and historical authenticity, and position within Australian motoring history. Each acquired and adapted this significant piece of the material past in a reflection of their contemporary interests.

This article has illuminated James Osborne as a man of means able to collect and sample European technologies as they became available for recreational and sporting enjoyment. In a rural setting of the 1910s, the Delaunay Belleville also functioned as a display of status and enhanced personal mobility. Osborne’s period of ownership was brief, and the car was swiftly replaced as its design and technology were superseded. Despite falling from favour, it remained functional in the ownership of William Sibley for the next 20 years. Although this era of its history remains shadowy and it was eventually abandoned to decay, it is evident that the Delaunay Belleville became strongly associated with the social history of the Gundaroo district, as recognised by the subsequent owner, Robert Beer. By the 1950s, the derelict car had acquired a patina of age appealing to the new breed of car collectors, who placed nostalgic emphasis on the material remains of the past within changed socio-economic circumstances. This indicates a critical transformation in attitudes towards historic cars, from a non-functional relic to a significant symbol resonating with the potential for restoration.

The Delaunay Belleville’s most fundamental modifications took place during the ownership of George Green during the 1960s, and reflect a boom in the popularity of exploring the performative and experiential elements of historic cars. During the 1970s, it became a central feature in Green’s Motorcade Park Museum, an institution that has emerged as an exemplar of many of the features of the ‘living history’ trend in museology. By the 1980s, just prior to its purchase by the National Museum of Australia, the car again featured in one of the intense national debates around the legislation of national cultural heritage export.

Now a museum object, the history and physicality of the car allows for the interpretation of both the role of the motor car in Australian social and cultural history over the twentieth century, and the preoccupations of the owners and collectors who ensured its survival today. Interestingly, the high degree of new material used during the reconstruction of the car does not seem to have been considered by the Museum staff who purchased it as detracting from its interpretative potential, a decision which remains sound today.[76] In adapting the valid principles of the Burra Charter on the conservation of heritage places of cultural significance, the car’s reconstruction may be recognised as a legitimate conservation process revealing of culturally significant aspects. Although the process of this reconstruction is not well-documented, and the project has suffered from lack of visual historical research to determine its earlier state, the material evidence for this era remains a critical part of this rare vehicle’s unusual provenance. The reconstructed body of 1968 can in itself be viewed as an act of interpretation, and as such is culturally significant for the information it conveys on contemporary attitudes towards historic cars. While for many visitors this is not evident from the object itself, with explanatory text labelling the car provides a range of interpretative potential for future exhibition use.

In retracing the history of the Museum’s Delaunay Belleville, this article has recorded a perspective on the way the motoring landscape changed over the 20th century, and a deeper understanding of the popularity of collecting and adapting historic cars in Australia, which reached its zenith during the 1970s. When the car arrived at the Museum in 1982, Alex Dix prophesised that ‘the history of Australian transport is central to an understanding of our past and will be a very important aspect of the Museum’s display and collecting activities’.[77] Taking into consideration the installation of large transport-related objects in the Museum’s Main Hall in late 2012, the establishment of open days at the Mitchell-based store in 2010, and the motoring history component of therecent Glorious Days: Australia 1913 exhibition, this car has proved to be a valuable addition to the National Historical Collection.

photograph by Po Sung, National Museum of Australia

Endnotes

My grateful thanks go to Col Ogilvie, Ian Stewart, David Hallam, Guy Hansen, Ray Sanderson, and the two anonymous reviewers for their assistance with this article.

1 Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the Car Won our Hearts and Conquered our Cities, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2004; John William Knott, ‘“The conquering car”: Technology, symbolism and the motorisation of Australia before World War II’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 31, no. 114, April 2000, 1–26; Rob Pilgrim, ‘The Blokemuseum: Motor museums and their visitors’, unpublished PhD thesis, School of Archaeology, Flinders University, 2005; and Margaret Simpson, On the Move: A History of Transport in Australia, Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 2005.

2 Martha Sear, Karen Schamberger, Kirsten Wehner, Jennifer Wilson, et al., ‘Living in a material world: Object biography and transnational lives’, in Desley Deacon, Penny Russell & Angela Woollacott (eds), Transnational Ties: Australian Lives in the World, ANU E-Press, Canberra, 2008.

3 The date of manufacture was determined after inspection by the Veteran Car Club of Australia in 1979. See ‘Certificate of dating for the 1913 Delaunay Belleville Tourer, issued by the Veteran Car Club of Australia’, Green’s Motorcade Museum collection (1986.0042.0002).

4 Pedr Davis, Veteran and Vintage Cars, Lansdowne Press, Sydney, 1981, pp. 96–7.

5 For example, French Peugeot, De Dion Bouton and Panhard-Levassor were several of the most sophisticated and sought-after marques. Shane Birney, Australia on Wheels: Early Beginnings to Present Day, Bullion Books, Silverwater, NSW, 1989, pp. 16, 22, 32.

6 ibid., pp. 20–31.

7 Michael Sedgewick, The 6-Cylinder Delaunay Bellevilles, 1908–1914, Profile Publishing, place unknown, 1966, pp. 3–4.

8 Quote from unknown motorist, ibid., p. 7.

9 ‘Announcement’, Australian Motorist, December 1909, n.p.

10 Ernest F Carter, Edwardian Cars: A Reverie of Adventurous Motoring, GT Foulis & Co. Ltd, London, 1955, p. 24.

11 A later owner recalled seeing a small brass plate on the bodywork identifying Cann & Co. as the coachbuilders. Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia, and Robert Beer, 27 October 1982, Prestons, NSW, National Museum of Australia file C1986/042, folios 133–41. The first owner took delivery of the car in May 1914: ‘Gundaroo’, Queanbeyan Age, 14 May 1914, p. 2.

12 George Oliver, Cars and Coachbuilding: One Hundred Years of Road Vehicle Development, Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications, London, 1981, p. 77.

13 The figure of £800 is quoted in ‘Motorists shot a policeman’, Adelaide Register, 1 April 1912, p. 8.

14 Border Watch, 20 September 1913, p. 1.

15 ‘An ideal car for Australia’, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 November 1913, p. 26.

16 ‘The Delaunay Belleville is an exceptionally reliable motor car’, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November 1913, p. 26.

17 In 1912, the car was available to purchase in grey or green, according to ‘Delaunay Belleville’ advertisement, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 January 1912, p .6. In 1955, Robert Beer described it as ‘white or buff or beige’; Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia and Robert Beer, 27 October 1982.

18 RM Hartwell, ‘Dalgety, Frederick Gonnerman (1817–1894)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dalgety-frederick-gonnerman-283/text5051, viewed 10 September 2012.

19 ibid.

20 For example, ‘Announcement’, Australian Motorist, and ‘Delaunay Belleville’ advertisement, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 August 1912, p. 7.

21 ‘Motor section – last word in automobilism’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 April 1912, p. 12.

22 Delaunay Belleville advertisement, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 June 1913, p. 21.

23 ‘Table 1: Motor and non-motor vehicle fatality rates, New South Wales, 1901–30’, in Knott, ‘Speed, modernity and the motor car: the making of the 1909 Motor Traffic Act in New South Wales’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 26, no. 103, October 1994, 221–41 (p. 224).

24 Davis, Veteran and Vintage Cars, pp. 96–7.

25 As recorded in ‘Naming of the Federal Capital’, National Film and Sound Archive (PMN004950).

26 Holderness Motorist’s Guide for New South Wales: Being a Complete Record in Numerical Order of all Cars and Owners Registered in New South Wales, and Containing Much Other Valuable Information for Motorists, March 1915 – July 1916, Holderness Motors, Sydney, 1916, n.p.

27 ibid. Osborne is also listed as the Delaunay Belleville’s owner in the 1917, 1918 and 1919/1920 editions of The Motor in Australia: Automobile Guide and Road Maps, also a Complete Record in Numerical Order of All Cars and Owners Registered in New South Wales, Atkins, McQuitty Ltd, Sydney.

28 Edgar Beale, ‘Osborne, Pat Hill (1832–1902)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/osborne-pat-hill-4344/text7053, accessed 30 November 2011.

29 Collection record REL/04694.002, Australian War Memorial: http://cas.awm.gov.au/item/REL/04694.002/, accessed 30 November 2012; Diane Langmore, ‘Jeffries, Maud Evelyn (1869–1946)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/jeffries-maud-evelyn-6834/text11829, accessed 30 November 2012.

30 ‘Death of Mr JBN Osborne’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 June 1934, p. 10.

31 Errol Lea-Scarlett, Gundaroo, Roebuck Society Publications, Canberra, 1972, p. 133; ‘Gundaroo’, Queanbeyan Age, 10 May 1907, p. 2.

32 Lea-Scarlett, Gundaroo, p. 133.

33 ‘Accident at Yass’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 February 1909, p. 6.

34 Lea-Scarlett, Gundaroo, p. 133.

35 ‘Shooting accident’, Queanbeyan Age, 16 September 1913, p. 2; ‘Correspondence’, Queanbeyan Age, 10 March 1914, p. 3.

36 Lea-Scarlett, Gundaroo, p. 133.

37 ‘Gundaroo’, Queanbeyan Age, 8 May 1914, p. 2. The Delaunay Belleville is most probably the vehicle referred to here.

38 Sir Henry Thompson, 1902, quoted in Judith Jackson, Man and the Automobile: A Twentieth-Century Love Affair, McGraw-Hill, Roseville East, NSW, 1979, p. 24.

39 Fernand Charron quoted in Sedgewick, The 6-Cylinder Delaunay Bellevilles, p. 3.

40 Pedr Davis, Wheels across Australia: Motoring from the 1890s to the 1980s, Marque, Hurstville, NSW, 1987, p. 87.

41 National Museum of Australia file C1986/042 makes repeated reference to the Delaunay Belleville appearing in a ceremonial parade during the opening of the Australian Parliament in Canberra. No evidence of this has been found with the exception of photographs taken by May Sibley, which indicate the family were present as spectators. It is suggested that the provenance has been confused with another historic motor vehicle held within the National Historical Collection, the 1926 Crossley landaulette (1988.0120.0001) which was used to transport the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) during the ceremony, and during their 1927 royal tour of Australia.

42 Kimberley Webber, ‘Women at the wheel’, in Charles Pickett (ed.), Cars and Culture: Our Driving Passions, Harper Collins and Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 1998, p. 97.

43 David Lowenthal, quoted in Graeme Davison, The Use and Abuse of Australian History, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2000, p. 13.

44 Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia, and Robert Beer, 27 October 1982.

45 ibid.

46 The riverine area around the Sibley’s home experienced flooding during this time, which may also account for the abandonment of the car: Lea-Scarlett, Gundaroo, p. 153.

47 Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia, and Robert Beer, 27 October 1982.

48 ibid.

49 Murdoch MacDonald owned the Delaunay Belleville for approximately one year. No information has been found and so this period of ownership is not discussed.

50 ‘Welcome to Greens Motorcade: A great way to spend the day!’, unpublished undated leaflet, National Museum of Australia file C1986/042, folio 7a.

51 ‘About us’, Veteran Car Club of Australia (NSW) Inc. website, www.vccansw.org/aboutus/vcca_aboutus.htm, accessed 4 October 2012.

52 ‘Greens motorcade: A selection of a collection’, IC Willis Photographics & Publishing, The Firm, Camden, NSW, 1981.

53 ‘Welcome to Greens Motorcade’.

54 Davison, The Use and Abuse of Australian History, pp. 12–13.

55 Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985, p. 399.

56 ‘Milestones of the Council of Motor Clubs NSW’, www.councilofmotorclubs.org.au/cmc-profile/milestones-of-the-cmc.html, accessed 4 October 2012.

57 ‘About the Museum’, National Motor Museum website, http://history.sa.gov.au/motor/about.htm,accessed 4 October 2012.

58 ‘Welcome to Greens Motorcade’.

59 Charles Pickett, ‘Car fetish’, in Charles Pickett (ed.), Cars and Culture: Our Driving Passions, Harper Collins and Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 1998, pp. 23–39.

60 Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia, and Robert Beer, 27 October 1982.

61 Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia, and Terry Cook, 22 November 1982, North Ryde, NSW, National Museum of Australia file C1986/042, folio 107–13.

62 ibid.

63 ibid.; Pedr Davis, Veteran and Vintage Cars, p. 96.

64 Will Hagon, ‘Dream dies on block’, Sunday Telegraph, 26 September 1982, p. 7.

65 There was a small amount of written information on each vehicle, although information was generally imparted to visitors via guided tours. Pers. comm., Ray Sanderson, 18 July 2012; ‘Welcome to Greens Motorcade’.

66 Interview between AJ Martin, National Museum of Australia, and Terry Cook, 22 November 1982.

67 ‘Welcome to Greens Motorcade’.

68 Anne-Marie Condé, ‘A “vigorous cultural movement”: The Pigott inquiry and country museums in Australia, 1975’, reCollections: A Journal of Museums and Collections, vol. 6, no. 2, 2011, http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_6_no_2/papers/vigorous_cultural_movement.

69 Ian Irwin quoted in Frank Longhurst, ‘Funds sought to bid for historic cars’, Canberra Times, 18 October 1982.

70 The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences is now the Powerhouse Museum.

71 During the 1982–83 financial year, the Museum operated on a budget of $190,000 to cover interim Council expenses, salaries and administrative costs. A little over 10% ($19,500) was allocated for new acquisitions. Correspondence between Interim Museum Council chair Alex Dix and the Hon. DT McVeigh, 7 October 1982, National Museum of Australia file C1986/042, folio 56–59.

72 Correspondence between Interim Museum Council chair Alex Dix and the Hon. DT McVeigh, 25 October 1982, National Museum of Australia file C1986/042, folio 62.

73 Des Griffin & Leon Paroissien, ‘Museums in Australia: From a new era to a new century’, in Griffin & Paroissien (eds), Understanding Museums: Australian Museums and Museology. National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2011, http://nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/DGriffin_LParoissien_2011a.html, accessed 13 April 2012.

74 Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Regulations 1987, Statutory Rules 1987, No. 149, as amended under the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986, Australian Government Commonwealth Law website, http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2004H02941, viewed 13 April 2012.

75 ‘Illicit traffic of cultural property’, United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization website, www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/movable-heritage-and-museums/illicit-traffic-of-cultural-property/; ‘States’ and ‘Dates’, Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization website, www.unesco.org/eri/la/convention.asp?KO=13039, viewed 13 April 2012.

76 ‘Definitions’, The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 1999, Australia ICOMOS Incorporated, Burwood Vic, 2000, p. 2.

77 Correspondence from Interim Museum Council chair, Alex Dix, and the Hon. DT McVeigh, 25 October 1982, National Museum of Australia file C1986/042, folio 62.