William Dargie's celebrated portrait of Queen Elizabeth II is one of the most recognisable examples of twentieth-century Australian portraiture. In examining its commission, creation and the dissemination of reproductions, this image emerges as a potent piece of material culture significant in the promotion of popular monarchism in mid-twentieth century Australia. How does it reflect the powerful relationship between the Australian people and the monarchy?Sir William Dargie (1919–2003) painted a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II in late 1954 to commemorate the monarch's first visit to Australia as part of the 1953–54 royal tour of the Commonwealth. In the ensuing years, this patriotic image was to become one of the most recognisable examples of twentieth-century Australian portraiture and synonymous with the presence of the monarchy in this country. In considering the portrait's wider social background, scholarly engagement over the past 20 years has done much to address the enduring presence of the monarchy in Australia and, especially, the 1954 royal tour as representative of a significant era of Australian cultural history. In particular, Jane Connors has highlighted the phenomenon of 'popular monarchism' as a vibrant aspect of Australia's experience of constitutional monarchy, which is critically distinct from the ongoing debate about whether or not Australia should become a republic. Manifested through the public celebration of the monarchy and the private collection of visual and material memorabilia, popular monarchism was probably at its height during the 1950s, yet continues to hold curiously strong memories for a generation of older Australians today.

____________________________________________________

Sir William Dargie (1919–2003) painted a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II in late 1954 to commemorate the monarch's first visit to Australia as part of the 1953–54 royal tour of the Commonwealth. In the ensuing years, this patriotic image was to become one of the most recognisable examples of twentieth-century Australian portraiture and synonymous with the presence of the monarchy in this country. In considering the portrait's wider social background, scholarly engagement over the past 20 years has done much to address the enduring presence of the monarchy in Australia and, especially, the 1954 royal tour as representative of a significant era of Australian cultural history.[1] In particular, Jane Connors has highlighted the phenomenon of 'popular monarchism' as a vibrant aspect of Australia's experience of constitutional monarchy, which is critically distinct from the ongoing debate about whether or not Australia should become a republic.[2] Manifested through the public celebration of the monarchy and the private collection of visual and material memorabilia, popular monarchism was probably at its height during the 1950s, yet continues to hold curiously strong memories for a generation of older Australians today.

Two contemporaneous versions of Dargie's so-called 'wattle painting' are held within publicly-accessible Australian collections.[3] A small number of later, differing versions are held within international collections. However the image was perhaps most familiar to the Australian public through the wide display of reproductions hanging in numerous banks, schools, hospitals, libraries and private homes across the country. Although public visibility of this material culture has decreased in recent years as Australia has looked to other symbols to define the presence of the monarchy, Dargie's familiar representation still commands recognition as 'the defining portrait of the Queen of Australia'.[4]

Images of royalty have long been manipulated to control particular social tensions and inspire certain loyalties.[6] Mid-twentieth century Australian imagery surrounding the royal family was no exception. Queen Elizabeth II has been immortalised in countless portraits and photographs throughout her reign. These fall into two distinct spheres: the officially commissioned or 'state' portrait and the multitude of popular commemorative items on which her image appears. Although a discussion of popular imagery falls outside the scope of this article, an examination of the official portraiture reveals much about the way in which she was presented to, and perceived by, her subjects.

Like many royal representations throughout history, the official portraiture of the Queen's early decades on the throne is particularly remarkable for the transparent messages it projects concerning the magnificence of her rule. In response to the popular demand for reproductions by official bodies of all kinds, the Queen sat for 22 artists of various nationalities during the 1950s and early 1960s.[7] For these artists, the depiction of the 'outward and visible signs of an inward and spiritual grace' was of paramount importance.[8] Echoing the lavish series of photographs produced by Cecil Beaton for the coronation in 1953, the imposing state portrait of 1954 by James Gunn, for example, shows a grave-faced Queen, sumptuously attired in her diadem and coronation robes by couturier Norman Hartnell. The divine longevity and power invested in the monarchy is manifested in the prominence given to traditional royal regalia. In contrast, Pietro Annigoni depicted the monarch in 1955 as a beautiful yet solitary figure profiled in a barren landscape, an unusual rendering that served to both isolate and objectify her monumental responsibilities. Imperial dominance was a theme further enforced by Edith Grace Wheatley in her representation of 1959, which depicted a smiling queen, also wearing her coronation regalia, but wading through a jungle scene alive with kangaroos, zebras, elephants and various other creatures symbolic of her dominions. Each of these portraits was reproduced and widely circulated. It is evident that official royal portraiture performs a propagandist function in asserting the mystical power of the monarchy, which is further disseminated through popular channels via reproductions and the media.

Although souvenirs relating to the royal family have been identified from as far back as the sixteenth century, from the nineteenth-century onwards the promotion of the royal family across the Empire and Commonwealth was intimately linked to the rise of the popular press.[9] In response, popular regard for the royal family as a domestic entity increased throughout the early twentieth-century. The advent of wireless hastened this trend. In 1932 King George V delivered the first Christmas speech, beginning an annual tradition that promoted the monarch's status as father-figure across the British dominions.[10] Ben Pimlott firmly identifies the domestic appeal of the royal family, suggesting that they represented 'the kind of brisk and open-shirted nuclear unit that breakfasted on corn-flakes and believed in outdoor fun and restrained procreation'.[11] Early to mid-twentieth-century popular monarchism was also fuelled by the material and visual culture associated with royal tours to Australia by members of the royal family in 1901, 1920, 1927 and 1934. Technological innovations in photography and printmaking further increased the accessibility of the royals through cheap reproductions of popular portraits on various media.[12] In Australia, the possession of small promotional items marketed to suit all income brackets was central to many individuals' participation in the birth, marriage, coronation and investiture celebrations of the royal family. These figured strongly in shaping the identity of the monarchy in Australia.[13] By the early 1950s, new networks of news agencies, the development of radio technology and, in Britain, the advent of television, allowed for lavish coverage of Queen Elizabeth's coronation and tour of the Commonwealth. The atmosphere of national and familial unity was at an all-time high and the Queen, as declared by royalist historian Sir Charles Petrie, the 'subject of adulation unparalleled since the days of Louis XIV'.[14]

This popular young royal was no stranger to channelling the visual power of representation characteristic of her reign. Within the Commonwealth, the Queen's image had throughout her life been employed to communicate certain messages or to encourage public support of the monarchy. In Australia, as elsewhere, circulation of domestic-inspired imagery cemented the royals as a moral and familial force. Known affectionately to Australians as 'Baby Betty',[15] images of the toddler received modest interest around the time of the 1927 royal tour of Australia by her parents, the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King and Queen). The combination of an everyday nuclear family with royal ritual and pageantry seemed to particularly appeal to an Australian audience. As the historian David Cannadine has suggested, it may be that 'the romantic glamour of anachronistic ceremony has become all the more appealing' when juxtaposed against a world of technological, societal and cultural transformation.[16]

Certainly these opposing forces were evident in Australian media coverage of the royal family. For example, several informal photographs of the 'charming' princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret, going 'for a stroll'[17] juxtaposed against a tense scene from within the British Parliament were employed in 1936 to effectively diffuse some of the negative attention surrounding the abdication of their uncle, Edward VIII.[18] During the Second World War, photographs of the uniformed Princess Elizabeth changing a truck tyre[19] and knitting garments for servicemen served to underscore the royal family's contribution to the war effort.[20] The popularity of the royal family remained strong in the post-war period and the idea of the Queen as a domestic and moral role model was firmly rooted in popular culture, particularly evidenced in the proliferation of newspaper supplements and commemorative volumes dedicated to the activities of the family.[21] Especially vivid in the case of royal portraiture, the visual and material culture of the past provides a powerful evocation of popular monarchism in mid-twentieth-century Australia.

In further examining the representation of popular monarchism during the 1950s, it is possible to speculate on the way in which both officially and unofficially produced images of the Queen functioned to serve colonial interests. In some cases the way she was represented was unabashedly influenced by local needs and expectations. Ben Pimlott notes that ephemera created for the Queen's visit to Fiji as part of the 1954 royal tour depicts the monarch with a remarkably broader jawline than she in fact possesses.[22] Similarly, Nkiru Nzegwu observes that Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu took controversial 'liberties with the royal lips'[23] in projecting an African aesthetic on his bronze sculpture of the Queen commemorating the royal tour of Nigeria in 1956.[24] As Sylvester Ogbechie has commented in relation to this work, such images demonstrate a shift in power relations between Britain and its former Empire.[25] They also satisfy nationalistic and social requirements at a particular point in time. Royal portraiture evidently has a degree of agency and as such can reveal much about the artist and the social context in which the artwork was produced. In allowing that Dargie's portrait of the Queen may also reflect aspects of specifically Australian social and political imperatives in the wake of the royal tour, it is pertinent to look to the relationship between this country and Britain during the 1950s.

The 1931 Statute of Westminster had begun the process of devolving lingering imperial control over the dominions of Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa. Although Australia's longstanding obligation to imperial authority had been transformed into a more voluntary relationship via a 'Commonwealth' united by an allegiance to the British crown, monarchical symbolism remained strong.[26] As the 'Head of the Commonwealth', the monarch's role required continued travel and diplomacy to maintain sentimental attachment in the absence of more tangible bonds. The royal tour of the Commonwealth, undertaken only months after the coronation, was a highly strategic diplomatic encounter that bolstered the historic alliances between Britain and her dominions despite the dissolution of the Empire and the vast geographical distances.

As this was the first time a reigning monarch had set foot in Australia, the tour generated enormous excitement, representing what Peter Spearritt has identified as a high-point of British monarchical symbolism in Australia.[27] This was an era in which various aspects of politics, education and society of the mid-twentieth-century promoted a reverence for the ceremonial aspects of inherited British institutions. As the latest in a succession of royal tours at regular intervals since the visit of Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, in 1867, the Queen's arrival seemed to validate the immutable and natural continuity of the history of the monarchy in Australia.[28] Jane Connors points out that the well-established Australian regard for the royal family had continued to grow in inverse proportion to their imperial sphere of influence, and by the time the Queen was due to arrive in Australia in February 1954 after a series of cancellations, the nation was giddy with anticipation.[29] Indeed, New South Wales Labor premier, Joseph Cahill, extravagantly likened the Queen's Sydney arrival to that of Governor Arthur Phillip's landing in 1788.[30]

These popular sentiments accorded with Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies' own high regard for the institution of monarchy.[31] Correspondence between the prime minister and James Paton Beveridge Snr, the managing director of Melbourne-based printery McLaren and Company, suggests that the idea of creating a recognisably Australian representation of the Queen was consciously developed almost directly after the coronation in 1953.[32] Menzies himself played a pivotal role in the initiation of Dargie's popular portrait. As art historian Sarah Scott has established, Menzies' personal taste extended to the en plein air style of the 'Heidelberg school' and he maintained a close link with Australian art through the Commonwealth Arts Advisory Board (CAAB), a division of the Prime Minister's Department.[33] Originally established as an advisor to the Historic Memorials Committee, this group appointed by the prime minister was influential in establishing the National Collection and early to mid-twentieth-century patronage of the arts. The prime minister and Beveridge were well-known to each other through their membership of the Melbourne Scots Club and their various involvements with the CAAB. The importance of a portrait of the Queen 'by an Australian artist for Australia' was first raised by Beveridge in the weeks following the coronation, citing the small number of poor-quality photographic images of the Queen in circulation. Many public and private institutions such as clubs and hotels had contacted McLaren and Co. seeking a suitable image of the Queen for display, prompting Beveridge to refer to the high demand for a good-sized reproduction of a portrait by an Australian artist 'to be our own property'.[34] The figure of the arriving monarch loomed large in the rhetoric of the CAAB that winter and several discussions were undertaken relating to the appropriate design of naturalisation certificates and suitable gifts to be presented to the Queen during the approaching royal tour.[35]

Arrangements for the prospective portrait evidently required little further debate. The artist of choice was mutual friend and CAAB member William Dargie, a portrait and landscape artist trained under Archibald Colquhoun (1894–1983). Having built on his reputation as a war artist with the Australian forces during the Second World War, Dargie was a leading figure in the mid-twentieth-century Australian art world. He was head of the National Gallery Art School between 1946 and 1953 and was to eventually become chairman of the CAAB from 1962 until 1973.[36] Even by 1953, at the age of 42, he had gained recognition as the seven-time winner of an eventual eight Archibald prizes and, as such, seemed eminently suitable to produce a portrait of the Queen. Dargie's realistic and painterly style appealed to Menzies, who made no secret of his distaste for more abstract forms of Australian art.[37] McLaren and Co. was noted for its quality reproductions of the work of popular Australian artists.[38] Beveridge clearly anticipated the popularity of such a portrait and the potential for sales of the print, offering to cover the costs if the copyright was retained by his company.[39]

Dargie, aware of the Queen's imminent departure on her Commonwealth tour, was prepared to 'drop everything' in order to travel to London.[40] Beveridge appealed to Menzies to arrange the relevant sittings in London, suggesting that this was an opportunity to foster 'the patriotic spirit of the Empire'. The Queen was unavailable; but Menzies was pleased to report that 'Her Majesty, with a view to offsetting the immediate disappointment that we all feel ... has graciously promised to give sittings to Mr Dargie after the Tour for a portrait which could then be a vivid memorial of her first visit to the Commonwealth'.[41] This is a significant early indication of the prime minister's interest in producing a recognisable Australian identity for the Queen.

With hindsight it is perhaps fortunate that the sittings could not be arranged prior to the Queen's visit, as the Commonwealth tour provided the artist with rich visual inspiration. The tour, between November 1953 and May 1954, generated a distinctive brand of imagery that was replicated in many domestic publications across the dominions. Part of a demanding itinerary that stretched across 13 countries, the eight-week visit to Australia took in all states and territories (except the Northern Territory) and a wide range of people, places, products and industry.[42] The emotions of pride and the lavish array of royal memorabilia generated by the tour served to remind Britain 'how much of the atlas could still be coloured pink'.[43] Also, as the historian David Lowe has shown, the visit was seen as an opportunity to promote the country's affluence in the post-war period. Atomic physics, industry and agriculture were intended to highlight Australia's global prominence, while the presence of many children, the Queen's future subjects, illustrated Australia's progressive and modernist view.[44] During the Australian leg of the tour, the Queen and her consort Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, travelled over 40,000 kilometres by car, train, aircraft and boat to see and be seen by an astounding three-quarters of the Australian population.[45]

The enthusiasm in mid-twentieth-century Australia for such symbols of British imperial power requires some explanation. Australia was home to a high proportion of people of Anglo-Celtic origin and regardless of the political and economic differences between the Commonwealth nations, the tour aimed to nurture an 'imagined community of a global British people'.[46] Henry Parkes' 'crimson thread of kinship' between Britain and Australians of British ancestry emphasised the unity of culture, language and kinship under a common allegiance to the crown. The visit perpetuated a sense of collectivism, particularly among 'new Australians', and was joyously proclaimed by Menzies as prompting 'the most profound and passionate feelings of loyalty and devotion'.[47]

Enthusiastic journalists portrayed an unprecedented level of mass excitement and anticipation. An entourage of more than 100 reporters and photographers from the Australian News and Information Bureau were officially associated with the visit and faithfully reported every move of the royal party. Cinema newsreels, radio, newspapers and magazines showered superlatives on the royal couple. Media consumption was an integral part of the tour and most promotional and commemorative material centred on the presentation of the attractive young Queen as both the divine representation of a timeless institution and a role model for women. Whether wearing couture evening gowns from London and Paris or sporting a casual, airy frock and a 'wide antipodean grin', she was celebrated as an emblem of femininity.[48] According to an official publication, the tour was 'a thunderous progress through thousands of miles lit to incandescence by the affection and enthusiasm of nine million devoted subjects'.[49] Buoyed by this extraordinary success, the Governor-General, Sir William Slim, swiftly arranged the necessary sittings for what would now be a commemorative portrait, and Dargie promptly set out for London.[50]

Dargie was accommodated in London by his friends Sir Neil and Lady Mary Hamilton Fairley at their flat in Duke Street, a short distance from Buckingham Palace. Despite his initial nervousness, Dargie established a rapport with the Queen over the course of five sittings in November and December 1954. He intended to 'paint my sitter as both a beautiful and very feminine woman and as a Queen' by drawing upon the imagery of the royal tour.[51] Describing her as behaving 'as naturally as if I were a friend who had called in for afternoon tea',[52] the dynamic between sitter and artist evidently enabled Dargie not merely to capture a good likeness but to record the overwhelming momentum of loyalty synonymous with the royal tour. By downplaying the symbols of royalty and giving precedence to Australian imagery, Dargie portrayed the young and beautiful monarch as seen by the crowds who had journeyed to view the royal progress. This familiarity was clear to one journalist, who declared 'Mr Dargie has depicted the Queen as known by the man in the street'.[53] This view was shared by the British media, who commented that Australians 'will welcome this pleasant portrait, which will perpetuate the Queen as so many of them saw her among them'.[54] Many elements of the image also were designed to appeal to a specifically Australian audience, in a supposed personification of the Queen's values and Australian interests.

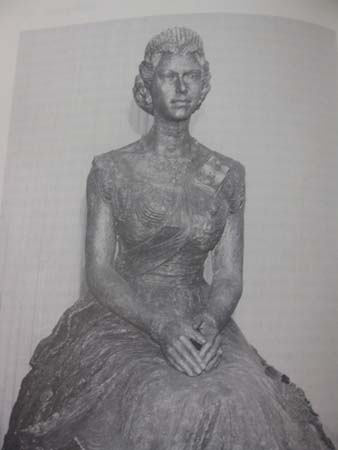

The glowing green-and-gold colour scheme skilfully captures the freshness of a young and regal woman in the almost impressionistic tonal style for which Dargie is celebrated. This soft realism also adhered to the aesthetic favoured by Menzies.[55] Dargie preferred his sitters to find their own pose while he put them at their ease by chatting and setting up his materials for the portrait, which is perhaps what eventuated with this commission — the Queen is shown informally seated against a greenish background with her hands folded simply in her lap.[56] Upholding his guiding principle as the 'imitation of things seen', Dargie captured the large-eyed, thin-lipped aesthetic common to English beauty.[57] One of the most striking qualities of the image is the glow of the Queen's skin, echoing the media reports surrounding the tour where much was made of her tantalising and apparently make-up free complexion.[58] This realism is further strengthened and humanised by the monarch's direct gaze, where a certain vitality is conveyed through skilful depiction of thoughtful eyes and expressive mouth. Her candid gaze conveys something of a warm personality often hidden behind her public persona and, indeed, she herself later referred to it as a 'nice friendly portrait'.[59]

from Royal Visit to Australia of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1954

Dargie appreciated the potential impact of this portrait and thought it might be the 'best woman's portrait' he had produced.[66] Naturally concerned that this significant canvas might be damaged or lost during transit to Australia, Dargie's decision to create two copies may well have been prompted by a letter from Beveridge, who mentions the fatal crash of a Trans-Australia Airlines Viscount aircraft after take-off from Melbourne's Mangalore airport during a test flight in October 1954.[67] Undaunted, Dargie commenced work on a second copy to be freighted separately, in the hope that 'at least one version' would arrive safely in Australia.[68] This 'spare' was painted upside down at the home of the Hamilton Fairley family in Duke Street.[69] Many artists will recognise this seemingly odd move as an attempt to view the portrait merely as a series of colours and forms. Eliminating the natural desire to improve upon the original, this endeavour prevented embellishment and resulted in an identical copy. As it happened, the original portrait arrived safely in January 1955, so the reproduction was not required.[70] The copy was sent to Australia briefly later that month before being returned to the Hamilton Fairley family, when Dargie gave the reproduction to Lady Mary in August 1955 during a visit to London.[71] The original portrait was officially presented to the Commonwealth by Mrs Janet Beveridge at King's Hall, Parliament House, in April 1955 and was received by the Prime Minister through the Governor-General.[72] According to Menzies, no portrait 'had ever given [the Queen] greater satisfaction'[73] — indeed the Queen later asked Dargie to paint a copy for her private collections.[74]

As Beveridge had predicted, Australians were pleased and flattered that a portrait had been painted especially for them. One journalist described the image as a 'superb example of Australian art'.[75] Another enthused: 'we now have in our own country a portrait of our Queen painted during the spring of her lifetime by a distinguished Australian artist'.[76] Within a short time of its completion, the work took on the status of Australia's 'state portrait'. Colour prints were in high demand. As material culture is significant in recalling and recounting celebrations and rallying national pride, it seems possession of a print of this portrait appeared to give meaning to individual experiences and recollections of the royal tour.[77] Straight away Beveridge's printery, McLaren and Co., swung into action, producing high-quality reproductions in various sizes and making them available for a 'modest price'.[78]

McLaren and Co. assiduously promoted sales of their prints, sending complimentary copies to all members of the Commonwealth parliament and to senior parliamentary officials.[79] As illustrated by the many requests for prints held in the Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, prints were ordered by unions, banks, schools, laboratories, clubs, offices of the armed forces and numerous private individuals and companies, not only across Australia but in Canada and New Zealand as well.[80] Later that year McLaren's associates, Legend Press Pty Ltd, administered the further distribution of a range of reproductions to institutions, groups and individuals, including 9500 prints distributed free of charge to schools throughout the Commonwealth.[81] This wide-scale dissemination clearly helped to prolong the celebration of the tour. In turn, the popularity of material culture asserting the Queen's Australian persona reflected popular memories of the visit.

The CAAB and the Department of Immigration had also set in motion plans to reproduce the image on Australian naturalisation papers. It was intended that the certificate 'should be of the greatest possible significance to the new citizen' as a 'symbol of his citizenship of his new homeland'.[82] The Department of Immigration encouraged new immigrants to adopt respectful attitudes towards the royal family.[83] The image became an integral component of naturalisation ceremonies. Under the terms of the 1954 Australian Citizenship Convention, a print of the work was generally present in local town halls, where many naturalisation ceremonies took place.[84] A royal presence was for many years a common feature in federal, state and local government departments, as well as countless public and private institutions throughout Australia: courthouses, schools, hospitals, libraries, church halls and RSL clubrooms. Within wider social changes surrounding Australian art and symbols of nation, the image on the citizenship certificate was replaced by the current design in 1973.[85] However, the implicit commitment of new citizens to royalty survived until 1992, when references to the Queen were removed by Prime Minister Paul Keating from the 'Oath of Allegiance'.[86]

The royal tour of 1954 was the high point of mass public celebration of the monarchy in the post-war Commonwealth. The following decade saw the slow decline of Australian focus on all things British and a shift in the place of the royal family in public and political affection. Although the Queen remained popular during her subsequent visits to Australia, especially the tour of 1963, the Prime Minister's sentimental attachment to the Queen was increasingly regarded as anachronistic.[87] Later royal tours were less grand and fewer people turned out to see the monarch, especially after the advent of television.[88]

Likewise, the declining public visibility of the 'wattle painting' in the early 1970s is thrown into relief against a re-evaluation of constitutional links to Britain. As author and social commentator Thomas Keneally commented in 1992, the attendant vestiges of material culture surrounding the role of the monarchy represent 'intriguing relics ... of a world which is almost gone'.[89] The cultural resonance of the 'wattle painting' became less relevant amid wider changes in the relationship between Australia and Britain during the 1960s and 1970s. The non-Anglo-Celtic population increased significantly after policy restrictions on non-white immigration were lifted.[90] The introduction of decimal currency in 1966, the dissolution of the Postmaster General's Department (and the abandonment of the term 'Royal Mail') in the mid-1970s and the replacement of imperial honours by the 'Order of Australia' all served to widen the distance. After a public opinion poll, God Save the Queen was abandoned for all but the most specific royal occasions, while Advance Australia Fair became the official national anthem.

However, while the importance placed on royal portraiture has changed as other forms of media become more dominant, Dargie's portrait remains a key reminder of the significance of the monarchy to Australians until the 1970s. Within wider discussions relating to the presentation of Australian art, the Australian Arts Council was formed in 1968 and the influential Commonwealth Art Advisory Board was disbanded in early 1973, thus enabling other forms of art to gain precedence.[91]

As historian Annette Shiell has shown, changing attitudes towards the monarchy are reflected in the material culture of the era, such as when comparing the reverential tone of royal souvenirs from 1954 and the cheeky souvenirs produced for the 1981 wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Lady Diana Spencer.[92] Changes in material culture can also be observed in more recent royal portraiture, where the Queen has cultivated an increasingly relaxed public image. Contemporary portraits by British painter Lucien Freud (in 2001) and Australian Rolf Harris (in 2005) mark a departure from traditional depictions of royal status in favour of representing aspects of the Queen's personality and an uncompromising attitude to her advancing age. Nonetheless, Dargie's 'Wattle Queen' of 1954 undoubtedly remains one of the most popular royal representations in Australian history, although today it has all but faded from view.

Despite the intervening years and shifting opinions towards the monarchy, the Australian Monarchist League continues to distribute prints free of charge to schools, clubs, youth groups and other associations, and receives several hundred inquiries per year from selected agencies.[93] However, the decreasing level of popular interest is a far cry from the passionate demand for this image that greeted its arrival in Australia in 1955. The portrait remains a symbolic reminder of the artistic and political spheres prevalent in the early years of the Queen's reign and an Australian society that has all but vanished.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

1 Peter Spearritt, 'Royal progress: The Queen and Her Australian subjects', Australian Cultural History, vol. 5, 1986, 75–94; David Lowe, '1954: The Queen and Australia in the world', Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 46, September 1995, 1–10; Jane Connors, 'The glittering thread: The 1954 royal tour of Australia', PhD thesis, University of Technology, Sydney, 1996; Mark McKenna, 'Monarchy: From reverence to indifference', in Deryck M Schreuder & Stuart Ward (eds), Australia's Empire, Oxford University Press, New York, 2008.

2 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 22.

3 One portrait is held in the Historic Memorials Collection of Parliament House in Canberra (where it remains on display). The National Museum of Australia purchased the second painting.at auction for $120,000 in 2009.

4 John Hamilton, 'William of the wattle', Herald Sun, 2 February 2002, p. 25.

5 Melissa Harper & Richard White, 'Land of symbols', in Melissa Harper & Richard White (eds), Symbols of Australia: Uncovering the Stories behind the Myths, UNSW Press and National Museum of Australia Press, Sydney, 2010, p. 10.

6 Helen Hackett, 'Dreams or designs, cults or constructions? The study of images of monarchs', Historical Journal, vol. 44, no. 3, 2001, 811–23; David Loewenstein, 'The King among radicals', in Thomas Corns (ed.), The Royal Image: Representations of Charles I, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999; Adrienne Munich, Queen Victoria's Secrets, Columbia University Press, London, 1996; John Peacock 'The visual image of Charles I', in Corns (ed.), The Royal Image.

7 Harold A Albert, The Queen and the Arts, WH Allen, London, 1963, p. 150.

8 Jane Roberts, Queen Elizabeth II: A Birthday Souvenir Album, Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd, London, 2006, p. 1953; Albert, The Queen and the Arts, p. 152. The expression was first used by Richard Hooker in the sixteenth century.

9 Annette Shiell, in Annette Shiell & Peter Spearritt, (eds) Australians and the Monarchy, Ideas for Australia Program and the National Centre for Australian Studies, Monash University, Melbourne, 1993, p. 35.

10 Robert Lacey, Royal: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Little, Brown, London, 2002, p. 115.

11 Ben Pimlott, The Queen: Elizabeth and the Monarchy, Harper Collins Publishers, London, 2002, p. 216.

12 Shiell, in Shiell and Spearritt, Australians and the Monarchy, p. 35. This concern is well illustrated by the National Museum of Australia's Sue Goss collection, which contains a scrapbook (object number IR 4893.0002) detailing media-produced royal portraiture over several generations. Other examples in the Museum's collections include the George and Sylvia Milne collection of royal portraiture on Federation-era decorations and the Cecil Ballard Jnr collection of commemorative china products.

13 As evinced by several National Museum of Australia collections, including the Cecil Ballard Jnr collection, the Professor Peter Spearritt collection no. 2 and the Jane Connors collection.

14 Quoted in Pimlott, The Queen, p. 215.

15 'Joyous reunion', Brisbane Courier, 29 June 1927, p. 15.

16 David Cannadine, 'The context, performance and meaning of ritual: The British monarchy and the "invention of tradition", c. 1820–1977', in Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983, p. 156.

17 The Queen's younger sister Princess Margaret was also a much-scrutinised public figure, not least in the early 1950s during her ill-fated relationship with her father's equerry, Peter Townsend.

18 'Recent pictures of the new Queen and two princesses — State Parliament debates bill on abdication', Sydney Morning Herald, 12 December 1936, p. 20; Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 85.

19 The Queen served in the Women's Auxiliary Territorial Service during the Second World War.

20 'Princess becomes transport driver and learns all about cars', Argus, 22 May 1945, p. 9; 'Princess Elizabeth', Argus, 18 July 1940, p. 3.

21 The Marion Butcher collection held by the National Museum of Australia holds many examples.

22 Pimlott, The Queen, p. 224.

23 Nkiru Nzegwu 'The Africanized Queen: Metonymic site of transformation', African Studies Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 4, 1998, http://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq/v1/4/4.htm, p. 3.

24 ibid. Also see Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, Ben Enwonwu: The Making of an African Modernist, Vol. 37, Rochester Studies in African History and the Diaspora, University of Rochester Press, New York, 2008, p. 138.

25 Ogbechie, Ben Enwonwu, p. 132.

26 Lacey, Royal, p. 115.

27 Spearritt, 'Royal progress', p. 86; also Bob Bessant, '"We just got to look at her": Propaganda, royalty and young people: Victoria 1900–1954', Critical Studies in Education, vol. 38, no. 2, 35–59, 1997, p. 36.

28 For a fuller discussion of the first royal visits to Australia, see Connors, 'The glittering thread', pp. 55–86.

29 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 83.

30 McKenna 'Monarchy: From reverence to indifference', p. 266.

31 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 215.

32 James Paton Beveridge Snr left Scotland for Australia in 1912 and founded his printing business shortly after. He did not live to see Dargie's portrait of the Queen arrive in Australia in January 1955, and McLaren and Co. was thereafter managed by his son, James Paton Beveridge Jnr.

33 Sarah Scott, 'The politics of patronage: Exhibitions of Australian art in Europe 1956–1965', PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2005, pp. 1, 3–7.

34 Letters from James Beveridge Snr to Robert Menzies, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 18 June and 24 August 1953.

35 Scott, 'The politics of patronage', p. 26.

36 ibid., p. 18.

37 Sarah Scott, 'Imaging a Nation: Australia's Representation at the Venice Biennale 1958', Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 79, 2003, 53–63 (55–6).

38 'Soon we'll see our portrait of queen', Argus, 11 January 1955, p. 8.

39 This was mainly administered by McLaren & Co.'s associate John Brackenreg, director of Legend Press Pty Ltd, a Sydney-based distributor of books and prints of Australian art (Lloyd Rees, 'Obituary: John Brackenreg', Art and Australia, vol. 24, no.4, 1987, 486.

40 Letter from James Beveridge Snr to Robert Menzies, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 24 August 1953.

41 Letters from Robert Menzies to James Beveridge Snr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 14 October and 11 November 1953.

42 It should also be noted that various representations of Australian life were restrained or exaggerated. Aboriginal-inspired motifs and Aboriginality sat uneasily within a collage of European-derived Australian achievements (Connors, 'The glittering thread', pp. 258, 267).

43 Lacey, Royal, p. 197.

44 Lowe, '1954: The Queen and Australia in the world' (p. 2).

45 Connors 'The glittering thread', p. 2.

46 Mark McKenna, 'Crown', in Harper & White (eds), Symbols of Australia, pp. 33–7.

47 Brett, Robert Menzies' Forgotten People, p. 123.

48 Pimlott, The Queen, p. 224.

49 Australian News and Information Bureau, Department of the Interior, Royal Visit to Australia of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh, 1954, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1954, p. 101.

50 Letter to James Beveridge Snr from Robert Menzies, Roger Dargie Personal Archive, 27 August 1954.

51 Letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Jnr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 4 December 1954.

52 Letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Snr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 4 November 1954. Several artists were to comment on the Queen's loquaciousness (Pimlott, The Queen, p. 251; Ogbechie, Ben Enwonwu, p. 136.

53 Anon, 'Queen's Portrait at Gallery', Age, 24 May 1955, p. 2.

54 Anon, 'Mrs (illegible), Bulletin, 18 January 1955, page unknown.

55 Brett, Robert Menzies' Forgotten People, p. 149.

56 William Dargie, On Painting a Portrait, Artist Publishing, London, 1957, p. 55.

57 Dargie, On Painting a Portrait, p. 9.

58 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 321.

59 Letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Jnr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 12 December 1954.

60 Hans Nadelhoffer, Cartier, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 2007, p. 73.

61 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 261.

62 Letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Snr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 1 November 1954. Margaret 'Bobo' MacDonald was the Queen's nanny's assistant and later dresser, confidante and travel companion (Lacey, Royal, p. 85).

63 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 261.

64 'In Sydney and Canberra, they're talking about ', Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February 1954, p. 16.

65 'He borrowed the Queen's coronet', Australasian Post, 2 June 1955, p. 10.

66 Letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Snr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 10 November 1954.

67 Letter from James Beveridge Snr to William Dargie, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 3 November 1954; The 44-seater Viscount, seen as a triumph of Britain's post-war aircraft engineering industry, had been recently ordered from England at the considerable cost of £350,000 and was due to commence scheduled passenger flights after training had been completed ('Viscount crashes', Argus, 1 November 1954, p. 1; 'We enter a new age in flying', Argus, 14 October 1954, p. 7.)

68 As per inscription on reverse of portrait and letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Snr, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive, 12 December 1954.

69 Pers. comm., Ms Kirsten Cooke, 9 June 2009.

70 It is thought that Dargie flew home with the original portrait on 6 January 1955 (Letter from William Dargie to James Beveridge Jnr, Roger Dargie Personal Archive, 30 December 1954) while the replica arrived on a TAA Viscount on the 22 January ('New airliner brings sketches of Queen', Age, 24 January 1955, p. 5).

71 As per inscription on reverse of portrait and pers. comm., Ms Kirsten Cooke, 9 June 2009.

72 It remains on long-term display in the Members Gallery, Parliament House Canberra and is part of the Historic Memorials Collection.

73

Ceremony in King's Hall, Parliament House, Canberra, National Film and Sound Archive, 1955.04.21.

74 It is believed Dargie was commissioned to produce several other copies of this portrait during the 1960s and 1970s.

75 'Birthday debut for royal portrait', Age, 22 April 1955.

76 'Let all see it', Brisbane Courier, 15 January 1955.

77 Tarnya Cooper, 'Queen Elizabeth's public face', History Today, vol. 53, no. 5, May 2003, 38–41 (p. 40); Richard Dorson, 'Material components in celebration', in Victor Turner (ed.) Celebration: Studies in Festivity and Ritual, Smithsonian Institute, Washington DC, 1982, pp. 33–57; Peacock, 'The visual image of Charles I', pp. 188, 199.

78 'Dargie's fine painting of Queen', Mirror, 16 June 1955.

79 'Prints of the Queen — to be distributed to members of Parliament', McLaren and Co. file, Richard Beveridge Personal Archive.

80 ibid.

81 Letter from John Brackenreg to James Beveridge Jnr, 18 February 1955, National Library of Australia, MS 7752, Dargie papers 1941–1978.

82 Minutes of Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, 30 April 1955, National Library of Australia MS 7752, Dargie papers 1941–1978, p. 2.

83 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 123.

84 David Dutton, One of Us: A Century of Australian Citizenship, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2002, p. 17.

85 Immigration — Australian citizenship and naturalisation ceremonies — New Certificate of Citizenship, A12111, bar code 8278745, National Archives of Australia.

86 Spearritt, in Shiell & Spearritt, Australians and the Monarchy, p. 8.

87 Connors, 'The glittering thread', p. 331.

88 ibid., pp. 331–3.

89 Thomas Keneally, quoted in Pimlott, The Queen, p. 549.

90 Pimlott, The Queen, p. 549.

91 Scott, 'Imaging a nation', p. 53. For example, the Whitlam government modernist stance resulted in the controversial purchase of Jackson Pollock's Blue Poles which marked a departure from more established aesthetics.

92 Shiell, in Shiell & Spearrit, Australians and the Monarchy, p. 35.

93 Pers. comm., Mr Philip Benwell, Australian Monarchist League (AML), 17 June 2010. As a patron of the AML, Dargie offered permission to reproduce the portrait for sale through their website.