No matter how small

Every town has one;

Maybe just an obelisk,

A few names inlaid;

More often full-scale granite,

Marble digger (arms reversed),

Long descending lists of the dead

Geoff Page, 'Smalltown memorials'[1]

'Every town has one': a memorial to the dead of the First World War. Any traveller or tourist in Australia is likely to have formed the same impression. Many memorials were erected in the decade or so after the First World War by citizens' and municipal committees. Local war memorials are primarily expressions of communal mourning, but they stand as evidence too of civic identity and, perhaps, of a sort of grieving pride. As early as 1925, one observer thought that 'every hamlet and village, town and township has its Memorial Hall or Column'.[2]

Geoff Page's poem 'Smalltown memorials' was first published in 1975. By this time it seemed that in addition to war memorials, every town had, or was in the process of developing, a museum. Disused nineteenth-century shops and stores, hotels and dance halls, police stations and courthouses were being spruced up by local voluntary committees and filled with rapidly and often haphazardly acquired collections of domestic items, costumes, sporting memorabilia, Aboriginal stone tools, militaria, books and local records and newspapers. Sheds were built out the back for agricultural and mining equipment, buggies and carts. Rooms were often done out to reproduce parlours and bedrooms and nurseries in hazily defined, late nineteenth-century styles. Some energetic committees transported whole buildings — often old schoolhouses, churches and slab huts — from outlying settlements to a new site in their town. On a larger scale, whole towns were being declared 'historic' or 'notable' by newly-formed branches of the National Trust, with the intention of preserving buildings and streetscapes. Parallel to this were new tourist developments such as Old Sydney Town in New South Wales and Sovereign Hill in Victoria, where re-created 'historic' towns functioned as 'living history' museums. Alongside all these developments were private museums set up by enthusiastic hobbyists to show eclectic collections of tools, domestic and agricultural items, and natural history specimens. In one case, even live reptiles were included.[3]

By 1988, museum curator Mary-Louise Williams was writing that:

Museums are everywhere. Apart from the big ones in the cities, almost every country town has its local museum. Some of these are very good and some are very bad. Some are interesting, others deathly dull. Many get lots of visitors and others rarely see a soul.[4]

In the early 1990s historian Chris Healy visited Silverton, a former mining town in far western New South Wales, and found that, while its museum probably had been a meaningful place for the people who had put it together, once they had passed on the place became anachronistic; no-one could tell the objects' stories any more. With the gaze of an outsider he could not order the objects into a comprehensible collection, and the museum seemed like a 'graveyard of social memories'.[5]

Many of us have wandered through local museums and stood as Healy did in front of a glass cabinet containing strange mixtures of objects, both familiar and bizarre, and asked ourselves, 'What does it all mean?' Another question might be, 'What's the point of having all these country museums?' Anne Bickford asked herself this question in 1975. An archaeologist and museum curator, Bickford had been hired by a federal government committee to visit and report on local and living history museums in New South Wales. For it was apparent, by the mid-1970s, less than a decade after many of the new museums were established, that the growth was getting out of control. In April 1974 the Whitlam Labor government appointed a committee to inquire into the state of museums and national collections. 'Before my Government came to office no Federal Government had accepted any general responsibility for museums throughout Australia or for the preservation of their collections,' Gough Whitlam later wrote. 'As a result, vast areas of our national heritage had deteriorated or been lost entirely.'[6] The committee was directed primarily to inquire into the Commonwealth Government's national responsibilities and interests, but its terms of reference did allow it scope to inquire into museums right down to the local level.[7] In announcing the committee, Special Minister of State Lionel Bowen noted that despite great public interest and dedicated service, the development of museums and collections had been piecemeal, and valuable collections were at great risk.[8]

A broadly experienced committee was appointed under the chairmanship of Sydney businessman Peter Pigott. Among other members were Geoffrey Blainey, Professor of Economic History at the University of Melbourne, John Mulvaney, Professor of Prehistory at the Australian National University; and Frank Talbot, Director of the Australian Museum. The committee advertised for public submissions in April 1974, and handed down its report on 5 November 1975 (just days before the dismissal of the Whitlam government). That document has been known ever since as the 'Pigott report'.[9]

The Pigott report is a key development in the history of museums in Australia, especially for its recommendation that a national museum be established and opened in Canberra, an ambition that was achieved in 2001. Less well known is the committee's interest in local, provincial, living history and private museums; a whole chapter was devoted to these in the report. Overwhelmingly, its interest was in country rather than suburban museums. The committee believed that their growth in the previous 15 years was a result of a 'quickening interest in Australian history', and that it had been 'primarily a grass-roots movement, one of the most unexpected and vigorous cultural movements in Australia this century'.[10]

My intention in this article is to take up this idea and, drawing on records accumulated by the committee, attempt to understand something more about this 'vigorous cultural movement'. Because, as with local war memorials, it can seem as if local museums have always been there, as immutable fixtures in the landscape; and furthermore that, as with war memorials, all local museums are alike. But local museums have not always been there. Most were established over a short period of time in the 1960s and 1970s. Why? What was going on at that time that could lead to this particular expression of culture, history and identity? And were local museums all alike? If so, why, and what does that mean?

In a discussion paper written in 1975 for the Pigott committee, its executive member, Peter Ryan, suggested that there were then more than 2000 museums in Australia, many of them local museums. Growth in museum numbers was a phenomenon that had occurred in many Western countries and Ryan wrote that in the United States, between 1965 and 1970, one new museum was reportedly founded every day. Numerically Australia's growth did not match that, but the growth in proportion to the Australian population was apparently more rapid than in the United States.[11] From early in the twentieth century growth in new historical societies were slow until, as historian Tom Griffiths has noted, numbers increased dramatically in the 1960s and 1970s. In Victoria, he found, the number of societies increased tenfold from about 30 in the mid-1960s to over 300 in the 1990s, and comparable growth took place in other states in the same period.[12] In 1973, at the height of the museums boom, Bathurst historian Theo Barker conducted a survey of the 147 historical societies then affiliated with the New South Wales-based Royal Australian Historical Society (RAHS) and found that 70 per cent of them ran a museum.[13]

Once past the 'bower bird' phase of early collecting, museums and collectors face difficulties and, in 1974–75, many small museums in Australia had reached that point. In its report, the committee noted that it had been advised that the buildings housing small museums buildings were usually inadequate, that the museums lacked professional staff and access to professional advice. Furthermore, the committee heard of:

the deterioration of many exhibits within these museums; the sameness of displays even when the opportunity for a distinctive theme is present; the scarcity of storage space; the absence of conservation facilities; the weak precautions against fire and dust and burglary and damp; and the unsatisfactory documentation of items in the collections.[14]

In an attempt to come to grips with what was happening in local museums, the Pigott committee visited 'some dozens' of them during its travels to all states. Unable to visit them all, it engaged professional consultants to visit and report back on local, private and 'living history' museums in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia. Also available to the committee were the public submissions it received: over 400 in total, at least half of which were from small museums and private collectors. All of this evidence went on the public record. The submissions and consultants' reports, along with all of the other records accumulated by the Pigott committee, are held by the National Archives of Australia.

This article focuses on the work of five of the professional consultants appointed by the committee and given the task of visiting folk museums and (in some cases) private museums. Anne Bickford was a historical archaeologist who had also worked as a curator at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS) in Sydney. She toured and reported back on museums in the Bathurst–Orange area of central New South Wales. DJ Robinson was curator of technology at the Queensland Museum, and he surveyed the Darling Downs area of southern Queensland. Historian of South Australia, Ronald Gibbs, covered the Adelaide Hills, Murray Bridge and the Barossa Valley. He was an educationalist working at the Wattle Park Teachers' College in Adelaide. Working in the South Australian – Victorian border region was Mark Richmond, an archivist at the University of Melbourne Archives (UMA). Finally, Frank Strahan surveyed the Albury and Wodonga region, as well as Gippsland and north-east Victoria. Also from UMA, he held the position of University Archivist.[15]

Together, this group of experts covered the fields of museums, history, archives and archaeology. It was perhaps an odd assortment of people to survey historical museums, but in fact, as museum historian Margaret Anderson has pointed out, few of the capital city museums (from where museum expertise was likely to be drawn) were collecting and exhibiting on social history.[16] The 'social history curator' of today did not really exist then. The consultants' tours of country museums were not the first time that such museums had been surveyed — the Royal Historical Society of Victoria had conducted a survey of local historical societies, for instance, and the MAAS had surveyed museums in New South Wales — but the survey for the Pigott committee was the first time such an exercise had been carried out on behalf of the Commonwealth Government. It was, however, only a part of the much wider scope of work that was being undertaken by the Pigott committee, and that perhaps explains why nation-wide coverage of museums was not sought.[17] Exactly how the consultants were briefed by the committee is not clear either. Mark Richmond noted in his report that he had been asked to concentrate on museums 'that cluster on the main highways' (a request he ignored, as we shall see later). It seems that the consultants themselves chose the museums they would visit, possibly based on prior knowledge. All consultants wrote reports on the museums they visited and usually they attached photographs they had taken and leaflets and pamphlets they had gathered. A questionnaire was prepared (apparently by the Pigott committee's secretariat), which the consultants could use to gather standardised information from their museums, but only Bickford, Strahan and Richmond did actually use it, and then in different ways. The consultants' final reports all differ in length, style and approach. Bickford, Strahan and Richmond were quite free with their opinions; the others were more restrained. Nevertheless, all of their work adds up to a finely grained record of museums in those regions at that time, as seen through the eyes of a particular group of experts.

In appointing that group the Pigott committee relied partly on the connections of its members. Bickford was known to John Mulvaney, and Strahan and Richmond to Geoffrey Blainey. (However, in Robinson's case the Queensland Museum was engaged as the consultant and it made Robinson available for the task; the origin of Gibbs's appointment is uncertain.) The consultants were all city-based heritage professionals. It is true that, working for the outwardly focused University of Melbourne Archives, Strahan and Richmond were well in touch with regional Victoria, and Strahan had spent his childhood firstly in Wonthaggi, later in Albury. He was an active member of the National Trust and had a strong prior interest in the history and heritage of Beechworth.[18] But as far as is known, none of the five had experience working any length of time in a local museum. Regionally based experts were active and prominent in local history and museums. Eric Dunlop, a lecturer in history at the Armidale Teachers' College, for instance, was responsible for significant developments in local museums in his district and in New South Wales more generally. Similarly placed were Theo Barker, in Bathurst, and Keith Swan, in Wagga Wagga, and there may have been others whose work is not as well known. Later I shall mention Dunlop, Barker and Swan again because their published work provides us with an additional perspective on the activities of country museums in this period.

Here is a typical country museum. In Berry, on the mid-south coast of New South Wales, a local historical society formed in three small rooms at the back of the Berry Pharmacy. It was open to the public on Saturday and Sunday mornings, and Sunday afternoons by appointment. According to its representative, Mrs M Lidbetter, the museum's first objective was to 'preserve Berry's past' by collecting 'all types' of clothing, household utensils, tradesman's tools, farm implements and so on, 'as used by the early settlers in Berry'. It aimed to 'repair and restore these', and to display some and store others 'in such a way as to prevent further deterioration'. The museum's second major aim was 'to teach the youth of the district how former residents lived and worked'. The collection included 'relics' of Berry families, Aboriginal artefacts, fossils, maps, books, and other records that were 'available for research'. Clear and simple, this statement of aims and activities by a local museum leaves little to be desired. Berry was not visited by the Pigott committee's consultants but Mrs Lidbetter wrote to the committee submitting a statement of the museum's aims and activities. Its submission to the faraway committee in Canberra was one of the first that the committee received. Although the museum's focus was on the Berry district, the submission expresses a quiet confidence in its place in the local community and within the larger community of the nation.[19]

From Berry we can sense a confidence that there was something nationally important in what its museum was doing. Berry had something to say about itself on a wider stage, and indeed, at that time, many people felt that Australia too had something to say about itself and its place in the world. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the talk was of 'the new nationalism', a term promoted by Donald Horne in an article in the Bulletin in 1968. This involved an interest in things distinctly Australian, and in an Australian identity that recognised a post-Second World War loosening of ties with Britain. Australia need not and should not define itself in relation to Britain and Empire. New nationalism touched many aspects of Australian society, including heritage and museums. The establishment of the Pigott committee, and the earlier establishment in April 1973 of a committee under RM Hope to inquire into Australia's 'national estate' (that part of the natural and built environment deemed most worthy of protection) represent a recognition by government of a historic preservation movement that had existed since the 1950s. That movement developed as a counter to what, in the minds of some, amounted to a 'national hobby of demolition' of built heritage that wreaked its worst in Sydney. It was in Sydney, in 1945, that the National Trust came into being, and from there it moved into other states.[20]

New nationalism came in handy when framing the need for an inquiry into museums and national collections. In his submission to Cabinet proposing the inquiry, Lionel Bowen stated that such an inquiry would 'provide a positive focus now for our growing national feeling'. It would be a 'move symbolic of the "new nationalism"'.[21] Although not mentioned in the Pigott committee's final report, the concept does underpin the extraordinary confidence and vision that has made that document so significant in museum history in Australia. Two of the committee's consultants wrote as though new nationalism was at the forefront of their thinking. Frank Strahan thought that a new-found respect and affection for Australian history, particularly local history, was the basic reason for the recent establishment of most of the museums he surveyed. They were a response to the new nationalism, which for him was:

a post-second world war emergence, wherein Australians are aggressively (if rawly) aware of a separate identity, willing to take an unselfconscious look at themselves, and compulsively salvaging ... old blacksmith's tools, bottles, bed-steads or bicycles as a historic backdrop, justifying their new image.[22]

Having (it seems) read Strahan's report, Mark Richmond partly agreed, but he traced the 'noticeable re-burgeoning' of historical societies (which so often included museums) to the recent occurrence of centenaries of local government. Sometimes, too, the act of saving some threatened building then led to establishment of a museum, so as to justify the rescue. But especially noticeable to him was the establishment of museums as efforts to attract tourists. Strahan also found that 'tourist attraction' was a primary aim of all but one of the museums he visited, so much so that it could breed intense rivalry between towns.[23]

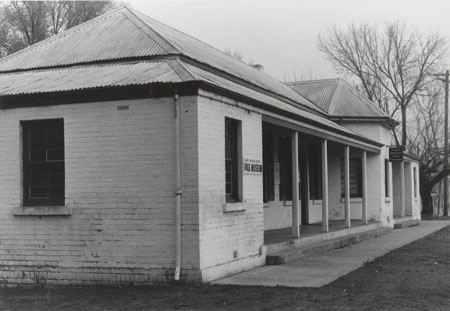

It is striking, then, that while the consultants for the Pigott committee expected that country museums would focus their collections and displays on the history or distinctiveness of their towns or regions, in most cases, museums did not. Ronald Gibbs's report on South Australia shows that for him the local history emphasis in small museums was extremely important: 'It is disappointing', he wrote, 'that the museums have a sameness about their folk displays. Far too little attempt is given to concentrate on that which is unique to the town and district'. His comments on each museum began with a summary of the town's geography and history. Kapunda, he observes, is one of the oldest towns in South Australia, noted for its copper industry as well as for pastoral and agricultural activities. The richness and diversity of its history marked it out from other towns. Gibbs then listed at length the main categories of items on display at the Kapunda Historical Museum — domestic items, pharmaceutical items, clothing, Aboriginal artefacts, war relics, typewriters, sewing machines — the list goes on. More attention should be given, he thought, to Kapunda townspeople, prominent and otherwise. 'Who were they? Where did they come from? What occupations did they follow? What distinctive qualities did they have?' And it was a pity, he thought, that the objects in the Aboriginal display came from another area and said nothing about the Aboriginal people of the Kapunda district. At the Strathalbyn National Trust Museum he thought the folk collection 'of no great significance' and needed to be pruned to draw out the material of real local significance. The original function and architectural significance of the main building, which had been courthouse and police station, had been ignored.[24] Mark Richmond also believed that the function of an old building needed to be respected in museum displays. In Beachport in South Australia the local National Trust had set up a museum in a former warehouse that had once allowed a railway line to pass right through the building. He lauded the museum's attempts to separately house and display material not relevant to the building or the district. He thought it should be developed into a wool and grain store museum. He noted that its Indigenous material came not from the local region, but from the Northern Territory.[25]

At the Federation Museum in Corowa, Frank Strahan found a notice at the entrance to the museum, originally a band hall, which read:

Welcome — Our history is old, but our Museum is young. In fact an infant of six months! Consequently these displays are mostly incomplete and we apologise for the lack of description. However, when next you visit the Federation Museum we feel sure you will note a great improvement. If you can assist with material, mention it to the attendant. Donation 30 cents.

Walking around to the rear, Strahan found his informant, a Mr N Macaulay, busy putting red paint on an old road-work lamp. As they spoke, Strahan asked the nature of this museum. Mainly local history, was the reply, 'but we're not goin' to try and stick to Corowa, we'll take all we can get'. The hall where the 1893 Federation conference was held still existed at the rear of a hardware shop, still with its multi-coloured plaster mouldings on the ceiling. It had been considered as a site for the museum, but was thought too small. Strahan found a 'mixed array' of poorly labelled items on display, including early agricultural tools, and Aboriginal artefacts not from the local region. 'Despite the museum's name', he remarks, 'I did not see one item relating to Federation' (his emphasis). Why then the 'Federation Museum'? he asked. Macaulay told him that originally it was going to be the 'Corowa Museum and Historical Society' but it was changed to 'Federation Museum', 'to give it more of a name'.[26] Strahan came away noting some local rivalry between museums in his district, but what is interesting is that this rivalry did not seem to translate into each museum seeking to define its own identity and distinctiveness over the museum in the next town. It seemed to be more a case of who could get the collections and open the doors the quickest. Macaulay of Corowa told Strahan that his historical society was 'late off the ground' in collecting the 'stuff lying about in people's places, going to waste', but that he had not seen other museums in the area except Beechworth. 'We were all mugs when we started off'.[27]

Strahan spent quite a lot of time in his home town of Albury, at the Turk's Head Folk Museum and the Albury branch of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS). These separate museums were co-located in the former Turk's Head Hotel on the Hume Highway near the bridge over the Murray. The building was flood-prone, security was inadequate, it was poorly sign-posted and difficult to see and reach for traffic in both directions. The attendant at the MAAS was an untrained caretaker, 'a suspicious but homely type' who refused to give his name to the Commonwealth's representative, and who complained that the folk museum in the other part of the building was a 'nuisance': it often didn't open and he had to take messages. Strahan found the MAAS displays strange: uncluttered, 'yet unrelated (more like bits of a museum than a museum)'. The historical society's museum, by contrast, had much less space, its collection was bigger but poorly labelled, and there were fewer visitors because the museum charged an entry fee. Strahan thought it the weakest museum in the district, and that the two organisations should combine. Jointly, they could develop thematic exhibits on local history and local industries.[28]

In the border country, Mark Richmond made an effort to survey museums off the main highways, for he observed that schools visits and local tourism were important parts of museum visitation. This broad approach led him to the doors of many private museums and he used tourism literature, including a booklet put out by the Western Wonderland Tourism Association, to identify some of his museums. Indeed, its editor, Mrs Vanda Savill, co-owned a museum at Heywood in south-west Victoria, aptly-named the 'Bower Bird's Nest'. Established in November 1972, there were 35 rooms and 100 separate collections displayed in sheds, barns, a former church and the Savills' house. According to its owners the effort was to 'preserve our heritage for the benefit of our family, our friends and visitors', and its purposes were 'educational, historical and tourist attraction'. No government aid had been sought or was required for her museum, according to Mrs Savill. Richmond thought it 'an almost meaningless agglomeration of cluttered collections', and that 'a real bower bird would disown it!' Security was provided by a Doberman and some Siamese cats: 'All appeared very friendly'.

Also from the Western Wonderland booklet Richmond learned of Riquier's Museum, about six kilometres east of Mount Gambier, but Madame Riquier declined to answer a questionnaire: 'I don't want the masses'. On display was a 'motley collection' mainly of European decorative arts. Elsewhere, searching for the poorly-signposted Caledonian Inn, near Portland, Richmond drove past it for several kilometres before turning back. This museum, run by a descendant of an early Portland family, was set up in a former roadside inn and Richmond obviously admired the building more than the collection, which consisted of a miscellany of items including the 'inevitable' butter churn. Not all the collection was local but the 'proprietress', as he called her, went to some trouble to obtain intact pieces of crockery to match the chips she discovered around the building.[29]

Frank Strahan also had a few adventures in private museums. At Lavington, near Albury, he called into Noel's Rock Museum and admired Noel Franks's well-organised collection of rocks and minerals, beetles, butterflies and shells. Franks was self-taught but knew his subject, and he 'personified his collection', Strahan thought, by giving 'individual dignity' to the specimens. 'He has the touch of eccentricity essential to a good private collector.' As a collector of renown for his own organisation, the University of Melbourne Archives, Strahan understood the passion of the collector.[30]

So, at an out-of-the-way private museum near Portland Mark Richmond had noticed what he called the 'inevitable' butter churn. How many other butter churns he observed in the course of his survey he does not say, but there certainly was a repetition of objects in country museums and they contribute to the 'sameness' Ronald Gibbs observed in South Australia. Some years later, Donald Horne called this phenomenon 'the cult of the flat iron'. In a lecture about museums delivered in 1986, Horne observed that at times, 'the flat iron can be seen as one of the greatest productions of Australian civilisation':

One can pass from one country museum to the other and see the same old flat irons, the same old typewriters, the same abandoned farming machines, the same photographs of the big flood of whenever, or the big fire of whatever, the same bed warmers and sewing machines [W]hat view of the distinctiveness of their own region do the people of these areas get from looking at objects that can be found from one end of the country to another?[31]

As we have seen, the Pigott committee consultants had been asking the same question. Perhaps this sameness in museums was more apparent to the outsider than the local. Ken Inglis has noted that local war memorials that feature the figure of a soldier often seem alike, but closer examination reveals differences in style.[32] Similarly, there may indeed have been distinctive features about local museums that were not obvious to an outsider, and that are lost to us now.

Nevertheless, not only were capital city-based experts commenting on the heterogeneity of country museum displays, but regional experts as well. Educationalist and prominent museum curator Eric Dunlop, in Armidale, wrote a booklet called Local Historical Museums in Australia, published in 1968 by the RAHS. In that he observed that while a lot of extremely useful collecting had been carried out, often the organisation and display of the material 'leaves much to be desired'. Done well, a museum could help members of a community to 'develop a deeper understanding of how their town or district came into being, and why it is what it is'.[33] Theo Barker went further. In an article on local history published in June 1975, he asked: 'What of the fact that these days tourists are getting a surfeit of butter churns and leg irons?' Already, he thought, there was far too much duplication. 'A museum ought to have themes for its displays but there is one theme above all others that should be stressed — it is, the history of this town or suburb.'[34] Barker was a local historian, president of Bathurst's historical society, and head of the Department of History and Geography at the Mitchell College of Advanced Education in Bathurst. Like Eric Dunlop, he was both insider and outsider, committed to localism but with a broader, academically trained perspective. And in Wagga Wagga, Keith Swan, local historian and prominent figure in the local historical society, had helped establish the Wagga Wagga Museum. He lectured in history at the Riverina College of Advanced Education and, in 1973, contributed two chapters to an important book on the practice of history in Australia at that time. There he discusses at length the establishment of several local museums in New South Wales, including his own, and notes the usual problems of too much clutter and too little money to finance grandiose dreams. He recalled that in establishing Wagga Wagga's museum in the late 1960s his society adopted as a slogan: 'Don't take your rubbish to the tip, but dump it on us!' Some good but much irrelevant material was gathered this way.[35]

Eric Dunlop died in 1974, too early to contribute to the Pigott committee deliberations, but neither Theo Barker nor Keith Swan was apparently invited to contribute either. Whether or not they might have offered a more nuanced and informed view of country museums than the committee's capital city-based experts is impossible to know, but it would seem that they too would have advocated a greater focus on localism in country museums. So, what was the point of all those flat irons and butter churns?

To answer that, let us dig down to the level of objects within displays. If, as Chris Healy found, museums later become 'a graveyard of social memories', what might those memories have been signifying?

Firstly, there are the rarities and the treasures. At the museum in Millthorpe Anne Bickford saw a 125-year-old apple in a jar. At Parkes she saw a piece of a bedspread, one foot square, allegedly worked by Mary Queen of Scots.[36] At the Turk's Head Folk Museum in Albury Frank Strahan saw a Haig & Haig whisky bottle apparently dating from 1679. ('If so, I'm 1,010', Strahan wrote.) At the MAAS in Albury he saw an object labelled 'Iron treasure chest (Cromwellian) — once belonged to explorer Hovell'. At Corowa he saw a cannon alleged to have been used by the police at the Eureka stockade. (It is possible that this was authentic, although it would have been used by soldiers, not the police.)[37] These were the weird and wonderful objects that could and still probably can be found sprinkled around the displays in small museums. They were not there to connect with everyday life as it had been lived in the local district, but with long ago times and far away places, which was something that museums have always done. Frank Strahan wrote that the Burke Museum, in Beechworth, had until very recently performed just that role, 'to provide contact with exotic places in the days prior to radio, film and television, and when travel was rare'.[38]

Most museum displays were however dominated by much more prosaic objects and, luckily, the text of the labels was sometimes noted. At Corowa, Strahan saw this: 'Milk basin used for setting milk. 100 years old'. At Turk's Head: 'Camp oven — In this cooking process the oven is set in the midst of the fire and hot coals heaped over it'. And this label was reported to the Pigott committee by a Melbourne-based historian who had seen it in an (unnamed) museum in country Victoria: 'Nancy Johnson's piss pot. She died aged 91'.[39] What is it that museums are trying to say in these labels? The aged-ness of the milk basin, Nancy Johnson and (by implication) her chamber pot, are important. They are 'by-gones' — a term frequently used in folk museums at this time — reminders of times gone by. Back in 1955 Eric Dunlop, in Armidale, had expressed his faith that museums could be something other than places of glass-topped showcases filled with heterogenous collections of objects associated with great men or events of our past. Instead, he thought museums could incorporate recreations of everyday life and allow the visitor 'a picture of what life was really like in the past'.[40]

Twenty years later, what had happened was that many museums were full of heterogeneous collections of objects associated with obscure people, and with minute events of everyday life, such as the act of relieving oneself into a chamber pot. But we should note that the word 'piss' made the function of the pot quite obvious, just in case anyone should miss it. The use of objects mattered enormously to small museum curators and private collectors. In a few effective words we learn how a camp oven works. In Wagga Wagga, Keith Swan noted that although he worked from documents, he soon perceived the research value of implements and other objects. 'I understood more about nineteenth century industrial and domestic life, for example, from studying pitsaws, adzes, mortising axes, camp ovens, butter churns and kerosene lamps.'[41] (Those butter churns again.) In Albury one private collector remarked to Frank Strahan: 'It is sad to see things of the past non-operational'. And concerning flat irons, another, rather irascible-sounding collector, Brian McGrath, told Strahan that he was worried that a young girl can look at a flat iron and ask where you plug it in.[42] McGrath was interested in early tools and his knowledge of their use was impressive. However, while viewing McGrath's collection, Frank Strahan noticed a beer pot labelled 'O'Donnell's Newmarket (Albury area) Hotel', and remarked in his report that McGrath had not been curious enough to find out anything about O'Donnell, the man, or his business. (Strahan probably did know something about O'Donnell.)

This obsession with objects for their own sake amounts to antiquarianism and while it was prevalent in historical museums in Australia at this time, it was also being subject to critique. There seems to have been consensus among all experienced and informed museum and heritage practitioners that museum objects should be displayed according to historical themes. Moreover, as Theo Barker put it, 'the history of this town or suburb' should be the overarching theme. The questionnaire that several of the consultants used to gather data specifically asked whether the displays were thematic. Usually they were not. Most museums grouped their objects by type, probably because it was intellectually and physically easier to do so. Anne Bickford reported that the groupings she observed in the museum in Bathurst were typical of the others on her list as well: Aboriginal artefacts, archives, gold mining objects, costume, postal and telegraph, typewriters, decorative arts and so on.[43] She was generally impressed by the dedicated effort she observed in country museums; but when answering the 'thematic displays' question at the Millthorpe museum her patience ran out. 'No. Typically arranged in groups', she writes. 'None of these museums have a concept so sophisticated as themes and it is a silly question.'[44] She did not visit any private 'rock and bottle' museums of the type that Frank Strahan and Mark Richmond saw, so she probably did not encounter the worst. Mark Richmond admitted that he had a liking for 'old style' museums. At Mount Gambier he visited Black's Museum and viewed a collection of seashells, gem stones and minerals, firearms, coins, swords, Aboriginal artefacts, 'and the like' collected by Mr Black and his late brother. Mr Black 'likes his seashells the best'. Richmond thought it the sort of place that fascinates children. 'It has a value at that level, but it is a level which I find hard to define — is it simply entertainment?' he wondered.[45]

Of course, between the weird (the 125-year-old apple) and the mundane (the chamber pot) many objects in many museums were significant and relevant to the particular history of the district. Many museums had collections of photographs, archival records and local newspapers that were unquestionably important. In Bathurst, for instance, Anne Bickford saw some rare, possibly unique, bound volumes of the Bathurst Times from 1867. In Parkes she admired a room set up with early gold mining equipment: a gold washing cradle, a set of gold scales and two bullock-hide buckets used to remove water from mines. These were at least 100 years old, she thought.[46] At Kapunda, in South Australia, Ronald Gibbs spotted a solid silver cup which had been presented to Charles Hervey Bagot, politician and successful mine owner at Kapunda. It had been recently valued at $3000.[47] However, the ability of museums to make the most of their collections was hampered by poor standards of cataloguing, indexing and 'authenticating' of objects. In Australia in the mid-1970s advice for small museums on how to set up such systems was scant, although in South Australia and Western Australia technical manuals for small museums were starting to appear. One of them advocated the use of trade catalogues as means of dating everyday items.[48] 'Provenance' and 'significance' — terms that now dominate if not define the field — were not apparently then in use. The concept of provenance in museums was developing, however. The historical importance of an object seldom lies with the object per se, wrote committee Secretary Peter Ryan, in one of his discussion papers. 'The value lies in its association with some person or event or its part in a chain of development.'[49]

made by Charles Edward Firnhaber

It is time to step back from objects and displays to look again at some broader patterns. A quarter of New South Wales country towns lost population between 1971 and 1976.[52] This is a stark statistic. Theo Barker analysed the contours of rural decline in a short work of historical geography published in 1975 as Towns and Villages in New South Wales.[53] The founding of country towns in New South Wales peaked around the turn of the twentieth century and had virtually ceased by 1939, Barker writes. The period between the wars was when the country town reached its greatest development in the traditional sense. Typically it was quiet, isolated from outside influences, and its people 'had little interest in events beyond the district except for those of national significance'.

It usually looked like any other town, the main features of all of them being a street full of shops and hotels, a railway station (with a grain elevator if it is wheat country), a showground, hospital, saleyards, public and Catholic schools, churches and tin-roofed houses.

Barker then goes on to describe the influences, mainly changes in transport and communications, that led to the decline of inland country towns after the Second World War. By the 1970s, many towns were hoping that tourism would help reverse that trend, but, Barker writes, people in small towns were still apprehensive about the future 'as they become increasingly aware of the empty shops in their streets'.[54] The 1960s and 70s was precisely the time when so many new museums were being established in country towns, sometimes in those same empty shops. To the tourist or traveller today they may seem old — 'a graveyard of social memories' — but the sameness observed in country museums grew partly out of these processes occurring at more or less the same time in many districts in rural Australia.

It is interesting to note Mark Richmond's and Frank Strahan's observations that there was once something even older. Perhaps not many of the 'old style' private 'rock and bottle' museums, full of miscellaneous curios, have survived to remind us of that. Like Anne Bickford, Ronald Gibbs didn't bother with private museums during his South Australian tour. He was one a new breed who expected museums to address themselves specifically to the history of their districts. He thought museums should be supplementing their displays with more text, graphics and photographs, so as to better illustrate the themes. He also wanted to see more people in the displays. 'Who were they? Where did they come from?' he asked.[55] These are social history questions, questions about the lives of people within the context of the times and places in which they lived. Local businessmen, pastoralists, councillors and maybe some 'pioneering women' might well receive coverage, but few small museums, perhaps none, attempted to address Gibbs's questions in depth. He was well ahead of his time in asking them, let alone expecting them to be answered in local museums staffed by untrained volunteers whose time was often fully taken up fixing leaky roofs, dusting displays, accessioning collections, and coping with the politics involved in running a museum in a small town. Gibbs apparently did not consider that there were few models for setting up a historical museum in Australia. The state museums were generally still not collecting or exhibiting on social history themes and in this sense the country museums were ahead. Often the people running them would have seen no more than a few other examples of museums being set up in their local areas. Mr Macaulay of Corowa remarked, as we have heard: 'We were all mugs when we started off'.

While many museums must have struggled, nevertheless Anne Bickford's strongest impression after her visit to all her museums was the enthusiasm and dedication of the men and women who ran them, she said. They were 'humble and generous', and spent a lot of their own money on their museums without thought of reimbursement. All had donated objects to their museums. Most of all she admired her informants' personal connection with the past, and their detailed knowledge of the function of the exhibits. She found illuminating their discussion of how objects were made and used. At the historical society museum in Parkes the volunteer staff were uniquely qualified, she said, by their knowledge of the working of farm machinery and large transport items. One of them, Wilf Norris, was a retired farmer who had bred, trained, and used teams of draft horses in ploughing and in carting wool. It would be difficult to find anyone with greater knowledge of the artefacts of this work, she thought, and she recommended that such knowledge should be captured in videotaped interviews. Further out of town was the Pioneer Museum Park, an open-air agricultural museum which was the work of about eight elderly male members of the Parkes Historical Society, including Mr Norris and another man who was a retired blacksmith and carpenter. On the site were also three old buildings that had been transported from other places, a schoolhouse from Wongelea, a church from Cooks Myalls, and a church from Coobang. The communities that donated the churches were undertaking their restoration, and the museum volunteers put in their own money and a great deal of affectionate effort to the restoration of old machines they had worked with in their youth. A single remark noted in Bickford's report illuminates an entire aspect of this enterprise, and of country museums more broadly: Pioneer Museum Park needed more help, she was told, but retired farmers 'prefer to spend their time at the RSL or the Bowling Club'.[57]

Some elderly farmers live out their retirement at the RSL or the Bowling Club; others devote it to the local museum: reading between the lines in Bickford's report, we can just make out an impression that many people in country areas were coping with ageing, and more generally with change and decline in rural communities in the 1960s and 1970s, by involvement in their local museum. By this means they could ensure that their personal possessions and life experiences could be preserved and passed on. For the people of Cooks Myalls and Coobang, restoring their churches in a new site for new use might have helped ease the sense of loss that inevitably flows from the closure of country churches. Anne Bickford was frustrated by much that she saw in country museums but she was nevertheless impressed by how country museums filled an important community need by drawing the people together and involving them in their own past. She admired the strong sense of continuity and stability through time that country museums possessed. Canowindra was a good example: growth of nearby towns such as Cowra and Orange had left it with an uncertain future. So they set up a museum. For Bickford this seems to be, essentially, the answer to her own question: this was 'the point of all these country museums'.[58]

By the 1980s, as we have already seen, local museums were the subject of severe critique. This peaked in 1988 when historian Graeme Davison published an article that offered an incisive analysis of 'antiquarian history' as he perceived its practice in local museums.[59] What is evident from his article is that by that time, the sense that local museums had once been 'one of the most unexpected and vigorous cultural movements in Australia this century', had entirely disappeared. Antiquarian history, Davison said, can result in the uncritical nostalgia for the past that he thought prevalent in folk museums, which are 'usually dominated by an inner circle of community elders who jealously guard the collections and tribal memories that go with it'. They attract 'no more than a trickle of visitors on the one or two afternoons they are open'.[60]

Davison's analysis was characteristically careful and measured. In Britain, by contrast, critique of the 'heritage industry' in the 1980s was, in some sectors of the media and academe exceedingly shrill. This led in 1994 to an extensive counter-critique by historian Raphael Samuel. He wrote: 'Instead of condescending to heritage, or joining the chorus of recrimination and complaint against it, it might be more profitable for historians to speculate on the sources of its energies and strength'.[61] This is in part what this article has attempted to do. Our reading of the evidence gathered by the Pigott committee reminds us of a time, not so very long before, when local museums were new. 'Our history is old, but our Museum is young' said the notice on the door of the new museum in Corowa. That vigour in local museum development had its origins in the 1950s when the idea of evoking everyday life in the past in museums was new in Australia. By the 1970s, when rural communities were often in serious decline, museums were refreshed again by the 'new nationalism' that had by then emerged. The style of country museums was conservative and backward-looking, yet it was new. We see this mingling of anxiety and hope enacted in the Pigott record. Rather than merely accept the fact of decline and loss, many rural communities saw museums as a means of using the past to face the future more confidently. Viewed in this light, the sameness and antiquarianism evident in country museums take on meanings of their own, meanings that speak to a wider social purpose for museums than we normally grant them.

1 Published in Geoff Page (ed.), Shadows from Wire: Poems and Photographs of Australians in the Great War, Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, 1983, p. 70.

2 Ken Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd edition, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2008, p. 223.

3 Mark Richmond, survey of the Naracoorte Mission and Museum, 2–3 July 1975, A7461, 75/76. This and all archival material referred to in this article is held by the National Archives of Australia.

4 Mary-Louise Williams, 'Community museums: More to them than meets the eye', in J Horne, J Ingleson, L McCarthy & P O'Farrell (eds), Locating Australia's Past: A Practical Guide to Writing Local Histories, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1988, p. 209.

5 Chris Healy, From the Ruins of Colonialism: History as Social Memory, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1997, pp. 78–9. An earlier version of the reflections that arose from his visit to Silverton appeared in his chapter, 'Histories and collecting: Museums, objects and memories', in Kate Darian-Smith and Paula Hamilton (eds), Memory and History in Late Twentieth Century Australia, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994, pp. 33–51.

6 Gough Whitlam, The Whitlam Government, 1972–1975, Penguin Books, Victoria, 1985, pp. 573–4.

7 Museums in Australia 1975: Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections including the Report of the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1975, p. 1.

8 'Statement by the Honourable Lionel Bowen, M.P., Special Minister of State', 10 April 1974, A7461, 74/135, pp. 2–3.

9 Museums in Australia 1975.

10 ibid., p. 21.

11 Peter Ryan, 'Local museums', paper no. 7, discussed at committee meeting of 7/8 June 1975, A7461, 75/15 part 1; Museums in Australia 1975, p. 21.

12 Tom Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996, pp. 221–2.

13 Theo Barker, 'A view of local history', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 61, no. 2, June 1975, 120–35 (p. 121). The year 1973 was also the mean date for the founding of new historical societies in Australia generally. See Paul Ashton & Paula Hamilton, History at the Crossroads: Australians and the Past, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2010, p. 41. The growth of local museums has been observed through several important surveys. See for instance Margaret Anderson and the Heritage Collections Working Group, Heritage Collections in Australia, Report Stage 1, Monash University, Melbourne, May 1991, and Report Stage 2, Monash University, Melbourne, March 1992; and Shar Jones, Julie O'Dean & Anne Brake, Museums in N.S.W: A Plan for the Future, Museums Association of Australia, NSW Government and University of Sydney, Sydney, 1991.

14 Museums in Australia 1975, pp. 21–2.

15 ibid., p. 21. Other consultants were also engaged. Nancy Underhill surveyed art galleries in Queensland, NSW and Victoria, and Bob Reece and Jim Allen were engaged jointly to report on major Victorian outdoor living history museums (Sovereign Hill at Ballarat, and Swan Hill). Anne Bickford also visited two large living history museums in New South Wales (Lachlan Vintage Village near Forbes, and Old Sydney Town, at Gosford). However, art galleries and living history museums fall outside of the scope of this article, which focuses solely on small country and suburban historical museums.

16 Margaret Anderson, 'Selling the past: History in museums in the 1990s', in John Rickard & Peter Spearritt (eds), Packaging the Past? Public Histories, Australian Historical Studies special issue, vol. 24, no. 96, April 1991, pp. 130–141.

17 Another reason may be that the least populated states, Tasmania and Western Australia, had fewer museums, and some were visited by members of the Pigott committee itself.

18 Cecily Close, 'Frank Strahan (1930–2003)'; and Mark Richmond, 'Frank Strahan: Beginnings', both in Archives and Manuscripts: the Journal of the Australian Society of Archivists, vol. 32, no. 1, May 2004, 8–14, 14–19.

19 Submission from Mrs M Lidbetter, Berry Museum, 31 May 1974, A7462, 39.

20 Donald Horne, Ideas for a Nation, Pan Books, Sydney, 1989, pp. 36–43 (I thank Guy Hansen for this reference); Clem Lloyd, The National Estate: Australia's Heritage, Cassell Australia, Stanmore NSW, 1977, pp. 11–23; DN Jeans and Peter Spearritt, The Open Air Museum: The Cultural Landscape of New South Wales, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1980, p. ix.

21 'National collections', Cabinet Submission no. 846, 12 December 1973, A5915, 846, p. 1.

22 Frank Strahan, 'Consultant's summary report of a survey of museums in the Albury-Wodonga region, and of two museum projects in Gippsland', 26 June 1975, A7461, 75/77, p. 5.

23 Strahan, 'Consultant's summary report', p. 7; Mark Richmond, 'Interim report on survey of museums in the southern half of the South Australia–Victoria border region', 2–3 July 1975, A7461, 75/76, [pp. 7–8]; also Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors, chapters 10 and 11.

24 Ronald Gibbs, 'Report on some South Australian museums, 28 April 1975', A7461, 75/81, pp. 1–6 (Kapunda), pp. 7–10 and pp. 15–21 (Strathalbyn).

25 Mark Richmond, survey of the Beachport National Trust Museum, A7461, 75/76.

26 Frank Strahan, report on the Federation Museum, Corowa, A7461, 75/79.

27 ibid.

28 Frank Strahan, report on the Albury Branch of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, and the Turk's Head Folk Museum, Albury, A7461, 75/79.

29 Mark Richmond, report on the Bower Bird's Nest, Riquier's Museum, and the Caledonia Inn, A7461, 75/76.

30 Frank Strahan, report on Noel's Rock Museum, A7461, 75/79.

31 Donald Horne, 'Demystifying the museum', the second William Merrylees Memorial Lecture, Riverina-Murray Institute of Higher Education, Wagga Wagga, 1986, p. 14.

32 Inglis, Sacred Places, p. 168.

33 Eric Dunlop, Local Historical Museums in Australia, Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1968, p. ii. For a fine study of Dunlop's work, see Nicole McLennan, 'Eric Dunlop and the origins of Australia's Folk Museums', reCollections,: a Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 1, no. 2, September 2006, 130–51.

34 Barker, 'A view of local history' (p. 123).

35 Keith Swan, 'Recreating community life: The folk museum', in David Duffy, Grant Harman and Keith Swan (eds), Historians at Work: Investigating and Recreating the Past, Hick & Sons, Sydney, 1973, pp. 153-66. Swan also wrote the chapter 'Finding Interest and Significance in the Local Community', also in that book.

36 Apple: Anne Bickford, report on the Millicent and District Historical Society, [June 1975], A7462, 344 part 2. Bedspread: Anne Bickford, 'A survey of museums in central western New South Wales', [June 1975], p. 8, A7461, 75/77.

37 See Strahan's reports on the Turk's Head Folk Museum, the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, and the Federation Museum, Corowa, A7461, 75/79.

38 Strahan, 'Summary report of a survey of museums', p. 6, A7461, 75/77.

39 Submission by Wilson P Evans, Williamstown (Victoria), 23 May 1974, A7462, 37.

40 Quoted in McLennan, 'Eric Dunlop and the origins of Australia's Folk Museums', p. 131.

41 Swan, 'Recreating community life', pp. 159–60. In an article about Swan, Don Boadle has pointed out that this understanding was not actually mirrored in Swan's history of Wagga Wagga, published in 1970. See Don Boadle, 'The historian as archival collector: An Australian local study', Australian Academic & Research Libraries, vol. 34, no. 1, March 2003, p. 17, www.alia.org.au/publishing/aarl/34.1/boadle.html (accessed 30 March 2011).

42 Frank Strahan, survey and reports on Drage's Historical Aircraft Museum, Albury; and Brian McGrath, private collection, A7461, 75/79.

43 Anne Bickford, report on the Bathurst and District Historical Society Museum, A7462, 344 part 2.

44 Anne Bickford, report on the Millicent and District Historical Society Museum, A7462, 344 part 2.

45 Mark Richmond, report on Black's Museum, A7461, 75/76.

46 Bickford, 'A survey of country museums', pp. 3, 8.

47 Gibbs, 'Report on some South Australian museums', p. 3. The Bagot Cup has been recently exhibited during the Not Just Ned: A True History of the Irish in Australia exhibition at the National Museum of Australia, see National Museum of Australia — Story circle (http://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/irish_in_australia/story_circle/slideshow_1_6.html#slideTop).

48 'Manual for regional museums', prepared by the Regional Museums Committee, National Trust of South Australia, Adelaide, 1974, pp. A8–A9. The National Trust of South Australia enclosed a copy in its submission to the Pigott committee: see A7462, 150. In New South Wales, the state Ministry of Cultural Affairs arranged a seminar in Dubbo in May 1974 entitled Managing a Country Museum. It was attended by representatives of several museums in the central west of New South Wales. More seminars of that nature were planned. See 'Report of the Ministry of Cultural Activities for the year ended 30 June, 1974', Parliament of New South Wales, Sydney, 1975, pp. 11–12.

49 Peter Ryan, 'Local museums'.

50 Museums in Australia 1975, p. 22.

51 ibid.

52 Jeans and Spearritt, The Open Air Museum, p. 41.

53 Theo Barker, Towns and Villages in New South Wales [Mitchell College of Advanced Education, Bathurst], 1975.

54 ibid., pp. 40–7.

55 Gibbs, 'Report on some South Australian museums', p.[i], p. 6.

56 Mark Richmond, report on the Warracknabeal Historical Centre and the Hamilton Historical Society Museum, A7461, 75/76; Gibbs, 'Report on some South Australian museums', p.[i], p. 39. 57 Bickford, 'A survey of country museums', pp. 15–16; Anne Bickford, report on the Parkes and District Historical Society Museum (Henry Parkes Historical Museum), and the Pioneer Museum Park, Parkes, A7462, 344 part 2.

58 Bickford, 'A survey of country museums', pp. 17–18.

59 Graeme Davison, 'The use and abuse of Australian history', Australian Historical Studies, vol. 23, no. 91, October 1988, 55–76.

60 ibid., p. 66.

61 Raphael Samuel, Past and Present in Contemporary Culture, Verso, London, 1994, p. 274.