A friend of mine likes to say, only half-jokingly, that he judges an exhibition by the quality of the cards in the shop and the coffee in the cafe – probably not the only factors uppermost in the minds of, say, a teacher with a school group, a wealthy patron, the minister or an assessor wielding National Standards for Australian Museums and Galleries (2011). For another friend, what’s important is the average number of people he has to look past to see the exhibits. An entirely different measure is evident in the reported response of a visitor who left in tears after seeing the National Museum of Australia’s recent ‘Forgotten Australians’ exhibition, Inside: Life in Children’s Homes and Institutions, too distraught to return. Finally, I was once told of a member of the ‘Stolen Generations’ who gained her first ‘link-up’ clues from visiting, years ago, the My Heart Is Breaking exhibition at the National Archives of Australia.

What makes a successful exhibition? One in a physical venue I mean, displaying physical things, even granted web interactivity increasingly underpins everything about them. If there ever were a set of orthodox criteria to judge success, today the number of measures in addition to visitor experience is as varied as the categories of visitor. Of course, some indicators are more equal than others. The designer’s voice insisting on best practice to optimise the experience competes with many others at the exhibition planning table. Publicists, the development people, conservators, events coordinators, curators, security and finance ... the complete list is probably twice as long.

Libraries and blockbusters

Where then do visitor numbers fit? Now of course there are qualitative metrics such as ‘impact’: factors calling to mind the saying not everything that counts can be counted. Yet audience size still does matter, as seems the case in the specific library context of the exhibition under review. The National Library of Australia has made much of the fact that Handwritten: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Treasures of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, which closed in March 2012, attracted 73,000 visitors, its third highest ever exhibition attendance. By early February this year, it announced with some fanfare that Treasures, opened only five months earlier, had already attracted 50,000 visitors.[1] Indeed the Library says it was the runaway success of Treasures from the World’s Great Libraries in 2001, an unexpected blockbuster that had queues stretching around the main building day and night, that convinced it to begin planning and fundraising for a permanent gallery space for treasures. Libraries and blockbusters: how did it come to this?

National Library of Australia

When the Library opened in 1968, it had the southern corner of the Parliamentary Triangle to itself. There was no National Gallery nearby, and no Portrait Gallery, National Archives, Museum of Australian Democracy or National Science and Technology Centre either. But portents there were. Just as the custodial analogue certainties were beginning to crumble, another set emerged. The Library came to realise it was, to many, just another national cultural institution. It needed to compete.

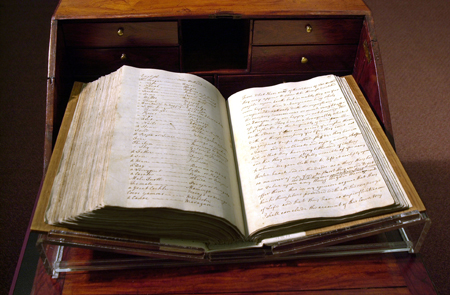

Its sumptuously appointed permanent Treasures Gallery, opened in 2011, is the culmination of a new emphasis for the Library that evolved from the mid-1980s when Warren Horton began two terms as its director-general. It is here that the historical context of the Treasures Gallery is to be found. We need to conjure a time when the public catalogue comprised endless drawers of cards located just beyond the entrance foyer; when navigator James Cook’s Endeavour journal rarely left the strongroom; when the licensed Bookplate cafe, its predecessor, Chapters, and even the obscure Brindabella Bistro did not exist. This was decidedly a time when exhibitions and outreach were functions of galleries and museums, not libraries. Advocates were ridiculed as children grasping at new toys to play with. The very idea of 12-metre banners suspended over each end of the elegant building beside Lake Burley Griffin would have been dismissed as tawdry. Horton, with others in secondary roles, was responsible for adding public programs, including the publishing of popular titles and touring exhibitions, to the Library’s priorities. The advantage of a long incumbency (1985–1999) and an ebullient forceful personality helped ensure they stayed. Poet and publisher Ian Templeman was recruited to lead a new Cultural and Educational Services division, the ground floor was remodelled, and catalogues and reference and reading areas were pushed back to make space for expanded visitor facilities and an exhibition gallery.

National Library of Australia

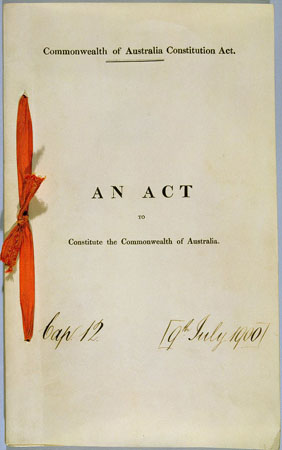

As an aside, there is an interesting parallel with Horton in the arrival in 1990 of George Nichols to lead the (then) Australian Archives. He too made a strategic judgement to establish, from scratch, its public profile as a cultural heritage institution and, in 1998, initiated its change of name to join the nationals. During his 10 years, a headquarters building was secured in the Parliamentary Triangle, and exhibitions and an outreach program begun. Today, the Archives’ exhibitions include the Federation Gallery with its so-called ‘birth certificates of the nation’. Beside that gallery is a larger space called ‘Memory of a Nation’, incorporating what its website describes as ‘the National Archives’ exhibition of treasures’.

National Archives of Australia

a new model of government, based on public choice theory, the outsourcing of functions, and private-sector emulation for government agencies, favoured reductions in public sector outlays and assessment of agency performance against narrowly-defined public value propositions.[2]

It was a time when government departments issued discussion papers titled What Price Heritage? (1988) and What Value Heritage? (1990), and when functions were identified as core and discretionary. The message was: generate more income and implement more user-pays services if you want to pursue non-core programs.

So the Library’s scholarly assets, acquired as information resources and selectively deployed as precedents to entice offers of complementary material, were put to a new third use. A publications list took shape that included coffee table books and beautifully designed titles drawing on the collections. Then came a bookshop to sell works such as, from its current list, editions of aviator Charles Ulm’s logbook and Governor Hunter’s First Fleet sketchbook. From 1990 the collections story was also carried by a monthly publication, National Library of Australia News, and, from 2009, an even glossier quarterly, the National Library Magazine. These built profile more quickly than they filled coffers. The serious money came from other sources. With help from people such as novelist Morris West and administrator, businessman and philanthropist Ken Myer, Horton and his staff pursued relationships with the corporate sector and attracted generous Australians who understood that there is more to cultural philanthropy than opera and art. This careful relationship-building and astute choice of Council appointments has paid handsome dividends. Over $3 million was contributed by donors and friends towards the Treasures Gallery, most from the Principal Partner, the Ian Potter Foundation, several supporters prominently named inside the gallery, and from within seven other levels of gallery partner from amber to platinum.

We will never know if the Horton strategic vision, endorsed by successive National Library Councils, was worth the cost and effort. The Library felt in some senses it had to compete in a space which had become quite crowded. Today it tries to please everybody across a spectrum bookended by two audience segments. At one extreme are those for whom, Derrida-like, there is nothing outside the e-text, and who do not care where the metadata and digitisation funds came from. Understandably, they are more excited by and derive more treasure from the Library’s online gateway, Trove, than an actual logbook whose informational content was long ago digitally liberated. If they ever visit the Library it is for the Petherick Room, reserved for scholarly research, not the Treasures Gallery. At the other extreme is the time-poor interstate visitor. Having ‘done’ the War Memorial, there is just time if parking permits for one further visit before needing to get back onto the highway out of Canberra.

The idea of treasure

So having noted the back-story, resigned ourselves to the Library’s need for a premier showcase gallery, accepted the inevitability of the lavish coffee table book,[3] and acknowledged the very high technical standard of the Treasures Gallery, what else can one say?

My answer begins with the idea of treasure/s. This should never ever be taken at face value. To me it conveys, like the whole design of the Treasures Gallery and associated web and print publications, a breathless pleading little short of embarrassing. (I suffer similar reactions when visiting the Australian War Memorial’s Hall of Valour and when urged by cultural institutions everywhere to share or find one’s story – apparently we all have one, at least one; and they are all fascinating.) The T-word has fostered a list of Library adjectives and phrases including – to sample just a single Library article coinciding with the gallery’s opening -unprecedented, dramatically suspended, surprisingly diverse, exquisite, extraordinary, singular, iconic and, three or four times, remarkable. On several visits for this review, trying to mask the hype, one wanted to shout back ‘Oh really, compared with which other library’s holdings?’, and ‘In whose opinion, other than the media unit’s?’ One secretly hoped to find beside Cook’s journal a little card, in the style of a Banksy graffiti silhouette, stating ‘This man was an agent of British Imperialism’.

National Library of Australia, inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register, 2001

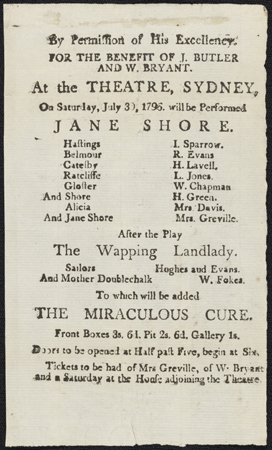

The Library has invested much thought and expense to arrive at the tone and style of the Treasures branding and the general feel of the gallery space. Doubtlessly just as deliberate was the decision to use in its marketing, without explanation, the handwritten word ‘Remarkable’ in a black thought bubble and an image of Nobel Prize for Literature winner Patrick White’s black glasses. Yet boosterism, even carefully considered, brings risks. Who ‘gets’ the glasses, regardless of whether they still carry the smears that once so excited a senior librarian in conversation with the Canberra Times?[4] Should the manuscript librarians then have collected a handkerchief, as they did White’s famous beret? It’s all White treasure after all. The problem is that what will intrigue some will irritate others. What some think rare and significant and a treasure, others will not. And despite smothering superlatives, those who actually care about time and history would notice, for example, the omniscient presumption in describing the Sydney Theatre 1796 playbill as Australia’s ‘earliest existing printed document’, as Australia’s ‘earliest extant printed item’. It is only in publicity for a recent book about the playbill and for talks by its academic author Gillian Russell you will find the qualification ‘so far discovered’.

National Library of Australia, gift from the Government of Canada to the people of Australia, 2007

And the exhibits themselves? Ultimately, any exhibition of treasures is a content-driven confection, the individual parts by definition greater than the contrived whole. It follows the Museum of Innocence reverse logic of Orhan Pamuk who, as Elif Batuman explained, ‘would buy objects that caught his eye, and wait for the novel to “swallow” them’.[5] However, even when the obligatory usual suspects themselves are the point, they have to line up in some order. For Treasures, the Library’s solution allocated the content to one of three sections, Realia, Terra Australis to Australia and NLA to Z. The sampling of realia begins outside the actual gallery. Why realia, why the particular selection presented, and why the foyer start I could not fathom. Terra Australis to Australia provided a vague framework of uneven chronology, not a strongly argued narrative. By contrast, the A to Z approach was a clever use of the abbreviation ‘NLA’ and disarmingly honest. Its panel explains, in typical boastful terms:

NLA to Z explores the extraordinary breadth and depth of the Library’s remarkable collections. There is no particular conceptual order for the exhibition, except for an alphabetical one – the selection has been chosen to entertain and surprise!

This allows anything thought to be a treasure to be dropped in, including Patrick White’s glasses. In the original selection some of the alphabet letters are used to display examples of documentary genres or media such as lontars, facsimiles, manuscripts and vellum. There is actually great potential here, as was evident in Handwritten and in a recent little gem in Sydney, the Justice & Police Museum’s exhibition Persons of Interest: The ASIO Files.

Indeed, one should acknowledge that exciting opportunities for the Library are now enabled, because the investment in a premium showcase gallery has been made. Having now ticked the Treasures box, it has a space ready to carry the best of the Library’s latest (physical) acquisitions, such as the rare terrestrial globe announced in March 2012. The Library’s premier gallery can also now demonstrate that an exhibition of content for its own sake actually can work, if cleverly thought through and appropriately disguised within legitimate micro themes. Good examples where the message is the medium abound, such as the recent exhibitions and matching publications from the State Library of New South Wales (ONE Hundred), the British Museum and the BBC (A History of the World in 100 Objects) and the Canberra Museum and Art Gallery (From A to Z: Robert Messenger’s Typewriters).

Rob Little Digital Images

Canberra Museum and Gallery

In an era of social media, there should also be room for what the public considers treasure, to balance the institution’s view. Room, too, we hope, for some self-awareness. To date in various Library publications there has been nothing more than the occasional paragraph (such as by Margaret Dent, Tim Bonyhady and Peter Cochrane) offering a passing nod to figured realities by, for example, placing the word ‘treasure’ in quotes.[6] So why not an exhibition that examines the historical, cultural and curatorial processes that produce treasure and by default leave non-treasure to a less certain fate? An anti-treasure stance might also be revealing. If ordinary Australians, and appeals to ordinariness, can have government-changing political force, why not display something of their ‘stuff’? To date it seems only in a work of fiction such as László Krasznahorkai’s War and War will an archivist have a box labelled ‘Family Papers of No Particular Significance’.

The treasure idea’s grip on the institutional mindset will not change quickly. There are I think two barriers. The first concerns the wide public recognition of the point of comparing collection items with treasure. And the media love it, readily accepting for reproduction press releases announcing a new treasured acquisition, restoration, exhibition or publication. Just in Canberra alone details of collection items have underpinned a regular radio program (Treasure Trove; Our National Treasures; ABC Radio, 666 Canberra) and several Canberra Times columns (‘Whiskers on kittens’ and ‘Hidden treasures’).

The second barrier rises because in contemporary Australia, cultural heritage institutions are seen to have much in common and there is talk of convergence, closer partnerships and even amalgamations. Repositories are being co-located and public access points shared. For at least a decade there has been a strong sense of a single cultural heritage sector, of common memory institutions, and of a unified collections gateway. All exhibit; all have treasures. Recalling the famous cartoon caption, ‘On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog’, should we now add ‘or a library’? To my mind, the National Library’s (and indeed the National Archives’) toughest challenge, having decided to compete with all other cultural institutions via public programs and exhibitions, is to do something other than produce even bigger blockbusters. Perhaps it is time to explain anew one’s differences in a distinctive voice and reassert one’s core identity, curatorial discipline and mission.

Next steps for the library

How? To end, here are four suggestions.

First, develop a more sophisticated, honest and hype-free collections apologetics; one alert to institutional hubris based on possession. One that emphasises, for example, the role of collections and information access in underpinning social capital, identity, literacy, an informed citizenry, public debate and scholarly and community discovery.

Second, adopt fresh approaches to treasures. For example, offer the Treasures Gallery to communities for exhibitions of Our Place/Our Street/Our Hall of Fame treasures drawn from the Library’s and their own collections. The first might be of ‘treasures’ from the local representatives of the people who originally inhabited the land on which the Library sits.

Third, stress again the unifying and ancient idea of information, or ‘the information’ as James Gleick wonderfully elevated it in The Information. A History. A Theory. A Flood.[7] For example, have an exhibition of the documents and paintings that historian Bill Gammage drew on to write The Biggest Estate on Earth, leading him to thank, in his acknowledgements, ‘my friends at the National Library of Australia’. He even quoted James Cook so, despite my being heartily sick of them, the desk and journal could retain pride of place!

Finally, however much reinvented, be a library. Be correctly identified as the library in a comparative ‘blind tasting’ where four or five different national cultural institutions each are challenged to design an exhibition using essentially the same content: let’s say a von Guerard painting, a First World War letter, a Gutenberg bible, a Tommy McCrae drawing, a Test cricketer’s diary, a Wolfgang Sievers photo, a convict uniform and an nineteenth-century banksia shaped brooch.

Endnotes

1 For the basic details of the National Library of Australia Treasures Gallery (including opening hours and checklist), see www.nla.gov.au/exhibitions/treasures-gallery.

2 Ian McShane , ‘Museology and public policy. Rereading the development of the National Museum of Australia's collection’, Recollections, vol. 2, no. 2 http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_2_no2/papers/museology_and_public_policy/.

3 See Jennifer Gall, Library of Dreams. Treasures from the National Library of Australia. National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2011. Earlier examples include Anne Robertson, Treasures of the State Library of New South Wales: The Australiana Collections, Collins Publishers Australia, Sydney, 1988; John Thompson (ed.), The People’s Treasures: Collections in the National Library of Australia, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1993; Chris McAuliffe & Peter Yule (eds.), Treasures: Highlights of the Cultural Collections of the University of Melbourne, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2003; Bev Roberts, Treasures of the State Library of Victoria, Focus Publishing, Sydney, 2003. As this review was being finalised came news of the latest addition, Nola Anderson’s Australian War Memorial: Treasures from a Century of Collecting: see http://www.awm.gov.au/shop/item/9781742660127/.

4 ‘Going through the White pages’, Canberra Times, 7 April 2012, www.canberratimes.com.au/entertainment/going-through-the-white-pages-20120406-1wfzl.html

5 Elif Batuman, ‘Diary’, London Review of Books, 7 June 2012, 38–39.

6 See Margaret Dent’s introductory essay, ‘Time’s Treasures’, inTreasures from the World’s Great Libraries, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2001; Peter Cochrane (ed.), Remarkable Occurrences: The National library of Australia’s First 100 Years 1901–2001, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2001; National Treasures from Australia’s Great Libraries, Introduction by Tim Bonyhady, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2005.

7 Fourth Estate, London, 2011.