Water

H2O=Life

review by Daniel Connell

The polar bear, now a threatened species due to global warming

photograph by Lannon Harley

National Museum of Australia

The

Water: H2O=Life exhibition at the National Museum of Australia is a tour de force of words, images, sounds and tactile interactions and provides a comprehensive survey of the way in which water interacts with life on the planet and, in particular, with humans. There is great success in linking water issues and water facts with concerns and preoccupations that are part of normal life. The exhibition achieves a high standard of presentation. Captions are clear, accessible, interesting and challenging, with readers often asked to think about how they might change their own behaviour in light of what they are seeing. A wide range of media is used and the many interactive displays are effective in pushing people out of passive roles and encouraging them to rework and digest the ideas raised by the exhibits by answering quizzes, taking part in games and touching objects.

Examples of animals that can survive in sea water

photograph by Lannon Harley

National Museum of Australia

The exhibition starts dramatically by requiring visitors to walk through a fog of watery blue light that includes words for water from many languages. From there they undertake a densely packed tour of stimulating ideas and challenges that provides an international survey of a great range of issues involving water, ending with a special section on Australia. The water cycle is a key focus of the opening section. The exhibition explains the extraordinary chemical and physical properties of water, highlighting the central role that water has for all forms of life. A particular standout is the presentation of the way in which different types of life interact with sea water, the form in which most water is found. The relationship between animals and sea water is one of the highlights of the exhibition. For humans this is a formidable barrier but the exhibition succeeds brilliantly in explaining the ways in which some other species can filter freshwater even from sea water.

Moving on from the biophysical exhibits the exhibition reveals the more social dimensions of water. Its importance for the world's religions, its cultural role, the potential to be the vehicle for disasters such as the 2003 tsunami in the Indian Ocean and the heroic, imaginative and defiant ways in which we have tried to harness more of it over past millennia are all compressed apparently effortlessly into a dense sequence dealing with a great range of water-related issues. These include the important but often neglected topic of groundwater, ranging from the issue of arsenic pollution in Bangladesh to the unsustainable management of the United States high plains aquifer in the Midwest and the aquifers upon which towns such as Tucson in Arizona depend. The unresolved governance issues that will increasingly dominate the future of those regions are hinted at but not discussed. Implied but not made explicit is the prospect that unless the peoples involved stop over-drawing their groundwater, or find alternative sources, they will eventually have to move on, as do the inhabitants of mining towns who have to leave when the ore runs out.

The frog, an example of a sentinel species (meaning that they react early to pollutants)

photograph by Lannon Harley

National Museum of Australia

Social justice issues are a major theme of the exhibition, reflecting the reality that water is one of the great points of divide between the world's haves and have-nots. As the exhibition notes, over a billion people have no access to safe clean water, with devastating consequences. Further, the volume of water available in many developing countries is also insufficient. Water itself is hard to export or import but its products are not. The exhibition does an excellent job of illustrating the concept of virtual water: water embodied in other products, food and manufactures, which are easily transported. This is one of the main ways in which the wealthier nations of the world import water from elsewhere and deal with their water deficits. In those few developing countries with abundant land and water, this can be a mutually beneficial arrangement; but for many parts of the world such exports exacerbate their tensions, with the costs and benefits unfairly shared.

The start of the human story for water in Australia — the arrival of Aboriginal people in Australia 60,000 years ago

photograph by Jason McCarthy

National Museum of Australia

The exhibition is actually two joined together. The first section, which makes up the bulk of the show, is an international survey put together by the American Museum of Natural History. The second focuses on Australia pre- and post-European settlement. Entry to the latter is signalled by the haunting voice of singer Archie Roach. The significance of rivers for Indigenous Australians is justly emphasised, not least through the art of Ian Abdulla, an Indigenous artist working in the Riverland of South Australia, whose paintings powerfully evoke the river of his childhood. The achievement of Indigenous Australians in adapting to one of the world's most variable climates is justly celebrated (and evokes parallels with the adaptive skills of the Inuits illustrated in the first section of the exhibition). The integration of Indigenous water management skills with the wider cultural dimension of their lives is also brought out effectively. Photographs from the nineteenth century and examples of traditional technologies, such as the waterbags used for cooling water, the flimsy but clearly effective bark canoe and the processes used to extract water from plants, all provide impressive indications of their adaptive success.

The Murray cod, Australia's biggest inland fish

photograph by Jason McCarthy

National Museum of Australia

A striking item in the Australian section is the living Murray cod. Leaving aside concerns about the adequacy of the small austere pond that has been provided for such a large fish, the presence of a living object in a museum exhibition causes a psychological jolt which is an effective preparation for the photographs of boatloads of Murray cod caught back in the early twentieth century when there was still a substantial inland commercial fishing industry. That was before the introduction of carp, the modification of river habitats by structures such as weirs and barrages and the over-fishing that combined to drastically reduced the numbers of native fish. The story of the Murray cod provides a suitably iconic introduction to the theme of ecological decline that is the backdrop to the contemporary debate about the future of water management in the Murray–Darling Basin. (As is often the case, the Murray–Darling Basin tends to crowd out discussion of other regions in Australia, each with their own distinctive characteristics and issues. Areas such as the Ord River do get mentioned but issues relating to them are only very lightly developed.)

Building on the story of environmental decline over recent decades is the discussion of the current crisis in Australian water management. Problems such as over-allocation, increasing water salinity problems and competition between rural and urban stakeholders are presented and the Water Act 2007 is introduced as the vehicle for reform in the Murray–Darling Basin. Perhaps understandably however, given its complexity, the difficulties being encountered in its implementation are not discussed. This points to an issue that is always going to confront a museum exhibition — how should complex contemporary debates be handled?

This is an even more important question for the wider exhibition. A number of the major issues facing contemporary irrigation worldwide are presented in the exhibition but discussion of the overall challenge for human society is muted. The irrigation dilemma can be summarised quickly. As explained in the exhibition, about a third of the world's food supply comes from irrigated agriculture. The extra two or three billion predicted population increase in the coming decades will have to be fed almost exclusively from the same source. But the best areas for irrigation have already been developed, and most are declining in productivity (owing to soil salinisation, water logging, silting of dams, etc.). Unless this situation is dramatically reconfigured in some way — as yet largely undefined — the result will be untold misery for billions of people and devastating disruption for the rest, including Australians. (The current public debate about a few thousand here or there will look bizarre when viewed from the perspective of a few decades in the future.)

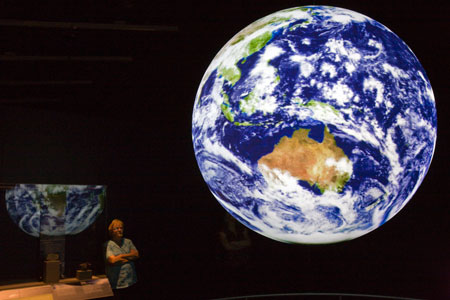

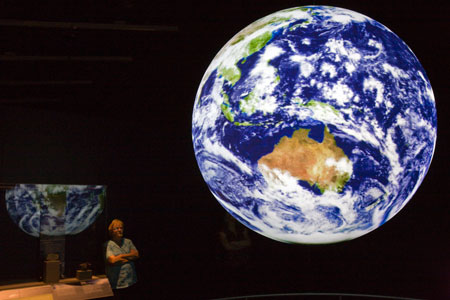

The earth, called 'the blue planet' due to all of the water visible from space

photograph by George Serras

National Museum of Australia

From this perspective the exhibition's coverage of China's Three Gorges Dam is disappointing. The environmental and social concerns listed are serious, but there is no real attempt to explain why the Chinese have continued to push ahead apart from an implied stubborn commitment to 'development'. The competing interests involved in such a project are an appropriate subject for such an exhibition; but given that the subject has been raised, there is an obligation to give the debate about sustainable development more considered treatment. With a population of 1.3 billion plus, many of whom continue to live in grinding poverty, the pressures on the Chinese Government to promote development are immense. If the argument were made that their approach will not meet its objectives or that there are better alternatives, discussion about the Three Gorges Dam would be very useful. Without that dimension, however, we are left with the needs of people versus the needs of the environment (and some social justice and equity concerns). That is not very constructive. In such a contest the environment will lose out every time. With a more nuanced approach, that does not need to be the case.

For people working in water research and education in universities, schools, libraries, broadcasting organisations, museums and similar institutions, the question of how best to present the need for sustainable water management is a serious challenge. In one sense this is strange in that what is being discussed is whether or not we can avoid ongoing decline in environmental conditions and resource security leading to lingering environmental issues and a food supply collapse, a result that will have horrendous consequences for billions of people. Surely there must be a way to make that interesting? There are no easy answers; but given the importance of this issue there should be more professional discussion about how best to explain what is involved to the general public.

Any publication or exhibition will be subject to interrogation as to its strengths and weaknesses in promoting wider debate (not least because there is wide disagreement about the nature of the issues and how people should respond). That is a demanding test but overall this exhibition at the National Museum passes it well. It has encouraged national and international debate about water and as such it is an important and valuable achievement.

Daniel Connell is a research fellow at the Crawford School of The Australian National University, researching the governance of rivers in Australia, South Africa, the United States, Spain and China.

| Exhibition: |

Water: H2O=Life

|

| Institution: | American Museum of Natural History assisted by the Science Museum of Minnesota |

| Curatorial team: | Eleanor Sterling (AMNH)

|

|

| Venue/dates: | National Museum of Australia, Canberra, ACT, 3 December 2009 – 16 May 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Exhibition: |

Australia's Water Story

|

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia |

| Curatorial team: | Matthew Higgins, Sharon Goddard

|

|

| Venue/dates: | National Museum of Australia, Canberra, ACT, 3 December 2009 – 16 May 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|