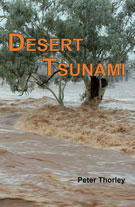

Desert Tsunami is both competent and understated. Yes, the title screams at you like a tabloid headline. But between the covers is to be discovered a meandering narrative of Australia's desert history — a multidisciplinary work — that roams and rambles like the desert's inhabitants have for over 30,000 years. In fact author Peter Thorley takes us back further, to the Cretaceous period between 135 and 65 million years ago to present a longitudinal study of Australia's climate. We travel with him through the Quaternary, on to the Pleistocene, the Holocene/present and Aboriginal settlement and European residency. If the reader's interests include the settlement patterns of desert hunter-gatherers, early European explorers, pastoralists and missionaries, or the rise of Alice Springs, then they will be absorbed.

This book has three overarching themes: temporal and geographical patterns of flood and drought in Central Australia, their influence on human occupation, and the social history of the region. While we learn about the physical effects of climate, I found the insights into human perceptions of flood and drought — and how these have influenced all human settlement — especially rewarding.

Of the present, it was with some irony that as I was reading this book in January 2010 a headline from an Australian on-line newspaper read 'Brothers swept away in Red Centre flood', an event that occurred north-east of Alice Springs.[1] Back in the Alice itself the police were door-knocking homes, advising occupants to be ready to evacuate. I was moved to contact an old friend in the desert to send me a tape of songs he recorded back in 1991, among which is Dam Song, a protest song about a dam that was proposed to be built just north of Alice Springs to mitigate flooding of the town:

Oh we're living in the desert

But you'd never really guess it

And we'll have its heart and soul

When the river's controlled ...[2]

Peter's book discusses the politics of flooding, from proposals such as the aforementioned dam, through to nation-building dreams to divert monsoon rainfall from the north to transform both land and climate and, at last, 'master' the desert.

Climate change is topical and political. Unfortunately one's views of its causes quickly descend into a polemic of support or opposition, left wing or right wing, black or white. Thorley addresses this important issue with deftness and dexterity. He argues, using the archaeological record and historical observations, that humans have advanced and contracted with the climate. Thus, he concludes, humans have previously made adjustments to a climate that was once as warm as our descendants will soon be facing. Climate change is one of a number of controversial issues discussed in this book; I did not come away feeling that I was being evangelised. Where other authors have left me feeling a little like I should seek redemption for my sins against the environment, Desert tsunami helped me understand my place in it.

Similarly, many writers on outback Australia have never captured the reality of the desert or Aboriginal life, only a romantic vignette which, in an act of conceit, imposes the author on the desert traditions. By comparison there is an intimacy and authenticity in Thorley's expression, which comes from having lived in the desert a long time and fully engaged with its people. Here is a person just writing it as it is, without posturing to be Australia's next desert sage or an expert on climate. There are moments of brave writing too. For example, on page 163 we read that 'After the arrival of white settlement, the provision of food and water on tap effectively removed limits on the scale of gatherings and allowed participants to pursue their ceremonial lives with a renewed vigour'. This is not an argument about the benefits or otherwise of white settlement. Nonetheless its objectivity will be difficult to digest for those who instinctively see all white influences in the Centre as inherently destructive.

Thorley's real mastery is in breaking down complicated concepts into simple terms. The second chapter, 'Unseen forces', provides a beautifully succinct explanation of pressure systems and their influence on climate, demystifying the hieroglyphics we see on weather maps each night on television.

There are some shortcomings. It is apparent that the publishers rushed to the first print as the editing should have been tighter, typographical errors removed, and commas redistributed. I would also like to see the illustrations, including the picture of the author on the back cover, made a lot clearer. And there is a sense of deja vu in some parts of the book, where Thorley summarises all that has preceded in the chapter, or where themes overlap or are revisited.

Nevertheless, Desert tsunami shines in stimulating the imagination to re-create desert flooding and its aftermath in times that none of us have seen (though are sometimes captured in Aboriginal traditions). I was engrossed in Thorley's reconstruction of the ancient drainage channels that feed into Lake Eyre and what these must have looked like in the past, the suggestion that the Finke River might once have flowed all the way there from its headwaters in the MacDonnell Ranges some thousands of years ago, and the retelling of major flood events through the study of the sediments they left behind. Could anyone have believed that it was only in 1974 that Lake Eyre filled to its greatest depth since white settlement and was surveyed in its entirety?

This book peels back layers of history, peering through the sediments of ancient flood deposits to show us how the land was once laid, how lives were once lived, and offering a vision for how the environment and life might be in the future in the Australian desert.

Brett Galt-Smith is former director of the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs and is currently an executive officer in the Australian Government, a civil marriage celebrant and a singer/songwriter.

2 'This piece of dirt', by Will Dobbie and Friends, Alice Springs, NT, 1991.