by Linda Young

It is widely known that the so-called Cooks' Cottage in Fitzroy Gardens, relocated from Yorkshire to Melbourne in 1934, was never inhabited by Captain James Cook. Yet a subliminal nationalism, sustained by the ancient traditions of contagious magic, feeds the conviction that the dwelling must be directly connected to Australia's foundation hero — a relic that the great man touched — or else it is meaningless. This paper tracks a sequence of managerial–interpretive strategies derived from a chronology of knowledge systems to make meanings at the cottage. It introduces evidence of the original shape of the building in its Great Ayton location, and observes the consequences on management and interpretation of an older demolition and consequent rebuilding of only half the cottage in Melbourne. Much turns on changing ideas about authenticity, as management strategies fail to engage the popular taste for a hero via the magic of faith. The result is a set of opposing principles in presenting the cottage: the role of the historical record as it has enlarged, and the desires of visitors who expect a simple connection between myth and materiality.

____________________________________________________

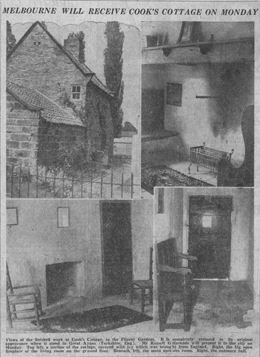

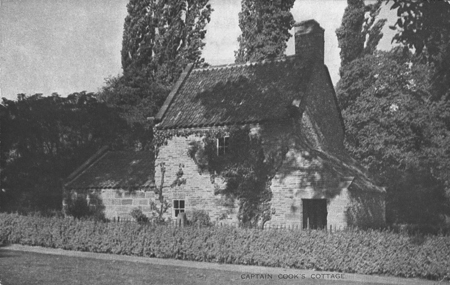

The charming little stone cottage (Fig. 1) is well-known to people who grew up in Melbourne, Melbourne schoolchildren, and Melbourne tourists. It is Captain Cook's cottage, a legendary piece of Yorkshire that was relocated from the village of Great Ayton to Melbourne in 1933–34: 1934 being the year of Melbourne's centenary of foundation. The site is known officially as 'Cooks' Cottage', with the apostrophe in a critical position, because this was the cottage of the Cooks, the parents of James Cook. If the date carved on the door lintel — 1755 — is reliable, the cottage was built 10 years after James had left home; in fact, the year he joined the Royal Navy. It is plausible to imagine that he might have visited his parents there occasionally, but his wife and children lived in London, so it has no domestic connection with the great navigator as child or adult.[1]

But even I, having studied the cottage's history carefully and written consultancy advice about it, cannot leave out the word 'Captain' when I say 'Cook'. It's just one of those phrases of common usage, where the words fall off the tongue, twined together. If you're an Australian reader, you probably have the same habit. This points to the deep presence in Australian minds of 'Captain-Cook' — the one who chased a chook, all around Australia (Lost his pants in the middle of France and found them in Tasmania). This mythic Captain-Cook is an avatar of the historic Captain James Cook who, as discoverer of the east coast of the continent and claimant of it for the British throne, is the foundation hero of this country, the source of white Australian history, legitimacy, antiquity. And this cottage has something to do with him — it must be his cottage, or else why would it be here?

I aim to explore this problem by tracking the history of the cottage as a device intended by its post-Cook owners and managers to present shifting inflections on the celebration of the great man. In practice, all their messages are subverted by the long-schooled conviction among Australian visitors that 'Cook' refers to 'Captain-Cook', a cliché of heroic nationalism, more akin to a magical hero of myth than a historic figure.[2] The tangle of beliefs, assumptions and plans that entwine the cottage has generated a series of impasses, sidestepped by successive managerial re-presentations. Each refers distinctively to the mentalities of its age, so it is not surprising to find that the cottage is once again overgrown with antithetical strategies and interpretations. Yet all the while, the continuing public taste for heroes and their tales of achievement demonstrates how little facts matter in the face of faith.

The topic of the cottage has been taken up or touched on by numerous critical writers.[3] Especially relevant to this account are Jillian Robertson, Chris Healy and Maryanne McCubbin. Robertson wrote the first extended treatment of the myth of Captain Cook, beginning bluntly, 'Cook's role as a super-hero is a completely false one'.[4] Healy distinguishes Cook the man from Cook the hero — a distinction I follow — and shows that, since the early nineteenth century, his depiction as hero converged in various social memories. Among them, the cottage's move to Melbourne in 1933–34 contributed to the maintenance of the narrative of imperial, racial bonds between Australia and Britain, in which context Healy suggests the authenticity of the presentation didn't really matter.[5] McCubbin takes up the topic to suggest that the cottage is a hybrid emerging between Healy's master narrative of imperial history and an antiquarian history of material evidence, both of them somewhat undermined by the sheer enthusiasm of the public.[6] But appreciating the undeniable public relish for Captain-Cook is inadequate in explaining more rational motives in the history of the cottage. I propose to look behind the relocation to its consequences, which continue to shape ongoing, everyday management — and that requires acknowledging both Captain James Cook and Captain-Cook.

My analysis suggests that a new perspective on both myth and history is opened by tracking the agendas of the cottage owners and managers, and the sequence of furnishing the cottage (its chief interpretive technique). I discern four paradigms of presentation: the eighteenth-century historical evidence of Captain Cook; the 1933–34 translation as a Victorian and Australian nationalist relic; a revision in 1976–78 led by the National Trust in the spirit of positivist Australian history, which framed a new career for the cottage as an object of heritage; and its 1993 transformation into a site of delicately allusive contest between the reality of the cottage and the interests of the stakeholders of Australian history, applied in a climate of tourism as the rationale of heritage.

by Phillipe de Loutherbourg

View larger image

In these images we see not just a fascination with the Royal Navy hero who perished in exotic circumstances, but a desire to commune with him through material connections. Characteristic of the urge is a little memento mori made for Cook's wife: a lock of Cook's hair in a small (9 x 7 centimetre) coffin-shaped box made from timbers of the Royal Navy brig Resolution, painted with a scene of where he died.[10] Grimm's drawings of houses inhabited by the Cook bloodline reflect the same mentality, expressions of the early modern episteme of collecting and documenting the world as history via specimens. It continues to thrive today, exemplified by the enthusiasm of museums to acquire the material evidence of heroes.

The cottage's apotheosis occurred in 1933, when the then-owners decided to sell. The Dixon family of Great Ayton had owned the house since 1873, though they didn't live in it.[11] Nonetheless, they had some sense of the building's venerable character, for they rejected an American bid to export it, specifying that the house should not be moved out of Britain.[12] Alerted by a Melbourne journalist, Hermon Gill, an ex-First World War-Navy man with maritime history interests, Melbourne magnate and philanthropist Russell Grimwade determined that the cottage should be acquired for Melbourne. Gill constructed a Cook–Melbourne connection, using the argument that the first Australian coastline observed by Cook's 1770 expedition, now named Point Hicks in Gippsland, was in what had become the state of Victoria. Since Victoria's capital, Melbourne, was about to mark 100 years of settlement, Gill suggested that Melbourne should become 'the proud guardian of the one-time home of the man who had made that Centenary possible, Captain James Cook'.[13] On this ground (and for more than twice the price offered locally), the Dixons were persuaded to permit the cottage to be sold within the patriotic sphere of Empire, and it was carefully demolished, packed up and shipped to Australia for reconstruction. A Dixon descendant later wrote that the day after the contract was signed they had a call from New Zealand House, enquiring about purchasing the cottage.[14]

A firm of architects in York, Brierley, Rutherford & Syme (BRS), was engaged to manage the relocation project. The only surviving records of the job are seven coloured drawings showing the cottage in the form in which BRS recommended it should be reconstructed, and a six-page specification for the demolition contractor.[15] Little is known about the original construction of the cottage; the earliest records date from its sale in 1772, when the widowed elder Cook went to live with his daughter. These 1772 deeds list 'two several cottages, dwelling houses or tenements' and name two other inhabitants and parties to the sale besides Cook senior.[16] The two tenements occupied a pair of adjoining one-cell, two-storey houses under separate roof structures, sharing a central through-passage, framed by a stone lintel engraved 'C/JG/1755', which was taken to refer to 'Cook/James & Grace [the Captain's parents]/date of construction'.[17] As depicted in the drawing by Grimm, both cottages were roughly square in plan, one a little smaller than the other. It is possible that, in the tradition of North Yorkshire through-passage houses, they constituted a long house occupied by two families.[18] An additional room up and down was added to the southern[19] cottage, involving relocation of its chimney. The date of this addition is unknown, the oldest evidence being the 1928 photo shown in Fig. 4.[20] The last occupants, the Simpson family, left the cottage in 1929, when most of the southern cottage was demolished for road widening, leaving a stump containing the through-passage still attached to the northern cottage.[21]

The Captain Cook Birthplace Museum/Middlesbrough Council

State Library of Victoria, SLV: H93.228/27

'Authenticity' is a chicken bone in the throat of heritage, as 'facts' are in the throat of history. Both concepts have plain meanings in popular understanding, namely, 'real' stuff and 'real' events. But professionals in both fields are more cautious, doubtful that either authenticity or the facts can ever be known with certainty. They prefer to regard informed interpretation of object, site and documentary records as arguments that stand until further evidence changes them. In this domain, to acknowledge an interpretation is an act of faith in the evidence.

The arguments against authenticity as an absolute are blunt. Ontology shows us that if something exists in certain conditions, it is authentic within those conditions.[24] This points to the essentialist view that the material character of things defines their authenticity. Hence the dominant modern conservation focus on original fabric and appropriate technique.[25] Further, the emphasis that Western thought puts on the first, the oldest, the original, endows it with an apparently natural primacy equating to authenticity, and devalues subsequent manifestations of objects' careers. A range of possible authenticities demonstrates that unless limits are specified (contingently admitting the existence of other limits), then a judgement of authenticity is an argument of conviction. In other words, recognising authenticity is a choice, a belief, an act of faith. Faith in relics has an ancient history in the traditions of magical thinking, expressed in what the early anthropologist of magic, James Frazer, called 'contagious' magic: it enables the transmission via contact of the magical essence inherent in certain items and places.[26] Religious relics epitomise the challenges to knowing authenticity, where the truth depends on proof by miraculous intervention, acquiescence to authoritative word, or unquestioning blind faith. Except for the first proof, the same conditions obtain among civil relics.

On this front, secular humanists from the Enlightenment to Modernism found it convenient to translate the power of relics into a sphere of civil religion, to validate nationalist or other political causes.[27] Even when the doubtful authenticity of many saints and their relics induced the Church to a massive revision in the late twentieth century, plenty of relics remained. Meanwhile, civil relics flourished in the care of museums. The stewardship of civil relics is now the domain of museum curators, whose professional techniques — from taxonomy and connoisseurship to the assessment of cultural significance and values-based management — offer systematic process and perhaps comparability of judgement, but cannot add any guarantee of authenticity. As Peter Howard writes, 'Authenticity is a slippery topic'. In a heroic effort to address the topic in textbook dimensions, Howard tabulates at least eight fields in which authenticity is discussed within the heritage business: authenticity of material, creator, function, history, ensemble, style, context, and experience.[28] It is an eloquent demonstration of professionals' techniques of theory to cope with multiple possibilities in, or relativist readings of, what they think is important to preserve.

Among such a range of possibilities, a sequence of uses of the cottage can be traced in which authenticity has been invoked. In the late eighteenth century, natural history defined the significance of Cooks' Cottage, derived from the famous sailor's association with the house. When Cuit sketched Yorkshire sites associated with Cook, the hero was alive and at the height of his fame as a naval explorer, advancing the interests of British power in the farthest reaches of the globe. The humble conditions that formed such a man were curious in the eighteenth-century sense of wonders of the world rather than particular to the man himself. Death translated him to the patriotic pantheon, which continued to fill with further Britannic heroes. The same vision of history informed the Dixon family to assert the special value of a cottage that by 1933 had been half-demolished: its sale was advertised as 'History under the hammer'.[29]

Come the 1930s, Hermon Gill invoked the old justification of reliquary honour for relocating the cottage to Australia, appealing to faith in the materiality of the building. Calling on a passionate imagination, he wrote, 'Its doorstep rang to his heel as he entered. Its walls heard his voice ... Within them must be stored memories'.[30] Grimwade's purchase of the cottage opened a new focus on Cook, driven by the need of Australia for a foundation myth that avoided its ignoble history.[31] As discoverer rather than founder, Captain James Cook constituted a bona fide hero untainted by convict stain, who could be acknowledged as author of the nation. Just as the 'sacred theft' of saints' bones around medieval Europe brought the blessings of their presence to their new owners, so would the patriotic delivery of material connected to the foundation hero endow legitimacies on white Australians.

State Library of Victoria, SLV: LTP 994.5 C77GI

The 1930s demolition and rebuilding of the cottage was an exacting professional business. But individual numbering of stones and tiles, and the labour and expense of transporting them to Melbourne, mask a suppressed history of the house. That it had been almost twice as big until just a few years before its sale did not appear in any records in Australia until 1993, when the Conservation Management Plan included the findings of research in Yorkshire. Hence the stump of the through-passage on what is now the south side was not understood, especially since its roofline had been altered by BRS in the reconstruction plans, in an attempt to make it look more normal and provide a front door to the public. The implications of the loss of fabric and knowledge reshaped the subsequent presentation of the remaining cottage as the home of the Cook family by making it express more modern values.[34] In this way the epistemic perspective of the cottage's authenticity shifted from being a site that demonstrated the nurture of a hero — a piece of evidence of history — to being a site that buttressed the Australian-ness of Captain-Cook, and the Britishness of Australia — proved by reliquary faith.

First, the new logic of the reconstruction produced a small, single-family dwelling, apparently detached, with no hint that it had been a tenement shared with other owners. Its lack of an external front door mandated keeping the stump containing the through-passage, an access arrangement that has not been explicable until now. The through-passage house plan was dominant in medieval England, surviving into the eighteenth century in houses of three or more cells, as in the case of the Cook et al. house; entry into the separate houses was off the through-passage, directly into the main room.[35] The newly presented single-family house now suggested respectable privacy, an improbable circumstance in the social register of the Cooks.

Second, BRS specified improvements to the kitchen fireplace to present it as an inglenook, by reinforcing the beam above the fireplace and inserting new bench seats (having 'remove[d] the appearance of newness'), on either side of the hearth.[36] An inglenook is not implausible in context, but its expression in the cottage was not quite obvious enough for the BRS vision. The firm may have been inspired by the inglenook reconstructed in the Pickering museum of long-time York folk collector Dr John Kirk, and reconstructed again in the York Castle Museum when it opened to house Kirk's increasingly important collection in 1938.[37] Inglenooks and other quaint features such as steeply pitched roofs and 'Jacobethan' furniture entered the repertoire of 1920s–30s revivalist taste, set off by collectibles such as samplers and copper bed-warming pans, which entered the cottage collection almost immediately it arrived in Victoria. The inglenook had come to epitomise a vision of the cosy life of the honest British yeoman in ye good olde times (Fig. 7).

photograph by Linda Young

Third, BRS either maintained or improved the fiction of three light stud partitions constructing two tiny separate bedroom-closets and a pantry. All would have been anachronisms in mid-eighteenth-century rural vernacular culture, though they may have been introduced by subsequent inhabitants. In rural vernacular eighteenth-century room use, bedrooms were arranged in the medieval style of many people sleeping in the same room. The husband and wife of a household occupied a large, curtained bed, and children and sometimes other relatives shared less grand bedsteads. Thanks to a 1976 review of furnishings undertaken by the National Trust, the 'bedrooms' acquired both reconstructed beds and gendered characters: the downstairs one containing a small sea chest marked with the initials 'JC'; the upstairs one with the subtle hints of a hat, shawl and dried flowers, clearly indicating feminine use.[38] The effect was to imply respectably single-sex sleeping among children, via low, narrow bedsteads (made in Melbourne) to furnish the tiny bed closets. At the same time, a wooden cradle was proposed to be acquired as 'a charming addition', although Grace Cook was 53 in 1755, and her youngest surviving child (of a total of eight) was 12.[39]

Fourth, BRS enclosed the chimney breast in the bedroom and inserted doors to create built-in wardrobes, an entirely twentieth-century fiction. Storage furniture beyond basic chests was unknown until the mass production of textiles in the late eighteenth century began to enable humble people to possess more than they wore or slept on. The small built-in wardrobes constitute surprising insertions in the cottage, for though echoing the conveniences of modern 1930s design, BRS clearly had knowledge of historic vernacular buildings. Posterity wonders at the solecism.

The genre of the historic house 'museumised' and interpreted by furnishings was quite well-understood in the 1930s in the United Kingdom. For example, the Dickens House opened in London in 1925 with family-provenanced and introduced furnishings, and Dr Johnson's house had been museumised since 1912.[40] In this tradition, Grimwade authorised BRS to commission a York antiques dealer to acquire £98 worth of furniture appropriate to a mid-eighteenth-century yeoman's station to despatch with the packaged cottage. Thus several eighteenth-century oak items, including a settle, dresser, gate-leg table and eight chairs, furnished the cottage when it opened in Melbourne (Fig. 8).[41] It was minimal furnishing, but a mid-eighteenth-century dwelling of Cook family status was indeed spare.[42] The effect was therefore impressionistic, but suggestive of real British antiquity, now made accessible to Australians. The public loved it, and wrote numerous letters to Russell Grimwade to say so.Having been gifted to the people of Victoria, the cottage's life in Australia came under the authority of Melbourne City Council, more because it had come to rest on council-managed land than through any active interest. This unsought status condemned the cottage to minimal ongoing management and abrupt, intrusive changes. After the rapture of opening on 21 December 1934 and a hectic year of attention, the cottage subsided from a spectacle to a curiosity. Access was unsupervised. Visitors trekked up and down the narrow stairs, then took a turn around the kitchen. The volume of traffic suggested to council managers that a door should be pierced through the side wall direct into the byre, and the upstairs closed off. Grimwade objected to both ideas, but council officers waited until he was overseas in 1936 to implement them. The patron was furious, and in 1937 he disowned the project.[43]

Thereafter, the cottage declined in popular favour and become unsavoury owing to constant vandalism. It was closed in 1940.[44] Though re-opened after the war, it was overlooked until civic preparations for the 1956 Olympics. In the early 1960s, the Melbourne City Council Parks and Gardens Committee took up with Victoria's new National Trust to reinvigorate the cottage, continuing the reliquary mode of presentation by adding specific (if wishful) Cook-associated objects and more furnishings for atmosphere, displayed in the new security of paid admission.[45] The Trust moved into a formal cooperative arrangement with the Melbourne City Council in 1976, following the Cook Bicentenary of the English discovery of Australia in 1970.The Trust was very aware of the new consciousness of 'heritage' that developed in Australia in the decade of the 1970s, introducing professional and academic approaches to managing historic sites. Hence expert reports were prepared on the cottage fabric, its structural condition and furnishing.[46] These papers acknowledged the doubtful connection between the great man and the cottage, but show that the Trust's vision was to interpret a big picture of Cook-era history via the visitor experience of walking through an authentic environment. The idea is fully expressed in the new garden developed for the cottage at this time, acknowledging that there was no evidence of any garden at all in its Great Ayton site, but planned to demonstrate the herbs, fruit and vegetables available in eighteenth-century England.

Under the new regime, architectural historian Miles Lewis made a detailed study of the cottage fabric as reconstructed in Melbourne, following which the door in the north wall to provide straight-path visitor access through the cottage was sealed, and the cobbled floor of the byre was re-laid.[47] Lewis concluded that the cottage had been substantially rebuilt from its original form (then unknown in Australia), though he summed it up as 'reasonably authentic'.[48]

John Rogan, a collector and member of the National Trust Council, advised that the furnishings should not be given 'an elaborate and romanticised treatment'.[49] He pointed out that separate bedrooms did not exist in the mid-1750s but proposed nonetheless to furnish the closets with reconstructed stump bedsteads.[50] Rogan noted that he was aware of a socially-comparable inventory of 1768 which included a four-poster and feather beds, but was convinced it was exceptional; since then the surge of inventory studies shows that such consumption was not exaggerated, even in rural villages.[51] He approved the National Trust's samplers hung on the walls as the only decoration; specified homespun window curtains; and introduced several crusie oil lamps to the numerous candlesticks throughout the cottage. All these recommendations could be revised today in the light of inventory research, which suggests a plainer, uncurtained and little-lit interior, but with more bedding than had been the conventional vision.

This degree of attention to historically reliable detail (as known at the time) in the cottage shifted the intellectual framework of its presentation to the public towards the performative platform of heritage. Cook was barely noticed in the cottage, but appeared in the cottage booklet, where he was contextualised almost entirely in his exploration career as Captain James Cook.[52] The change in focus speaks to the 1970s–80s era of Australian heritage management, exemplified by the original 1979 Burra Charter and its emphasis on the integrity of fabric as the expression of cultural significance.[53] Now, meaning was to be found in material authenticity, though just what the physical presence of the cottage and its furnishings meant elided into the inchoate social memory of Captain-Cook as the source of a collective national past.[54]This tiny structure stands today as a monument to Captain Cook and to Sir Russell Grimwade ... It provides Australians with a unique historic link to England and is a well-loved feature of the Fitzroy Gardens. It was originally erected by Captain Cook's father and was visited by Cook during his home visits. Detached from its village it reflects the architecture of the Great Ayton area. The interior is appropriately furnished.[55]

Thus guaranteed by a cautious yet positive statement of significance, the cottage was now managed essentially as a tourist destination, in the hope that its income would cover operational costs.[56] In these circumstances, it fell into a common trough of historic sites where uninformed management picks up after a specialist makeover. Little conscious management appears to have been applied throughout the 1980s, beyond marketing the site to tourists and tour organisers, for whom it represented an easy place to park a bus, a picturesque walk into Fitzroy Gardens, something to do with the national hero, and convenient toilets. Meanwhile in this decade, the bud of heritage was nurtured by growing public interest in family history, plans for commemorative spectacle for the forthcoming bicentenary of white settlement, and the burgeoning professionalisation of a new heritage industry. The latter's standards of care for sites of cultural significance now required that responsible owner–managers commission a conservation management plan (CMP) to evaluate how heritage significance is expressed in the structure, and develop a conservation schedule for maintaining the structure to protect its significant elements.

Architect Robert Sands was commissioned to produce the CMP. The brief specified an expansive cultural context: 'James Cook and his significance ... the nature of the empire ... Cook in the context of Australian history ... the nature of Cook as an Australian icon ... [the] removal of the cottage from its original location ... bearing in mind that legend might have its own right'.[57] This impelled the first professional research on the cottage in the North Yorkshire County Record Office, undertaken by Jonathan Clare, an Australian architect in London. He documented the ancient history cited above and located the watercolour by George Cuit, then attributed to Samuel Grimm, providing critical new evidence. The story of the relocation to Australia was contributed by professional historian Daniel Catrice, and the cultural context of the cottage in Australia was summarised by cultural theorist Chris Healy.[58] Healy's elliptical vision is evident in the Statement of Significance presented by Sands in the CMP:

Cooks' Cottage is of National Significance in that it physically and metaphorically represents the connection between a large proportion of the population of modern Australia, its history and its antecedents. It aspired to encapsulate a national statement as to Australia's origins for these people. At the same time it represents the opposite to another proportion of the population of modern Australia. These people believe it to mark the veritable end of an uninterrupted culture and isolation and the beginning of a long period of repression.

The Cottage provides an enduring opportunity to both recognise the nature of visions of history which have been important in the past and, by acknowledging how history-making changes, to continue the renewal of history by adding, juxtaposing and recognising different histories which are just as important.

The Cottage is of significance as a unique successful example of the international transportation of a local, non-transportable building with specific English and Australian references. The process of transportation and reconstruction represents a considerable creative and technical achievement in itself.

It is significant as the representation of Russell Grimwade's interpretation of the history of the development of Victoria, an interpretation popular at the time of the celebration of the centenary of the founding of Melbourne in 1934. It also provides tangible evidence of those centenary celebrations.[59]

The third element of the statement is incorrect: the relocation is not unique; aviator Bert Hinkler's house, a brick, two-storey Victorian number, was transported from Southampton to Bundaberg in 1983.[60] The other points are subtle in comparison with run-of-the-mill statements of significance. As parameters for the conventional purpose, i.e. physical conservation works, only the fourth element is likely to determine management decisions, namely, to maintain the reduced, 1934 shape of the building. The first and second items in the statement constitute a rhetoric that could direct cottage interpretation — but in practice, they don't. Rather, they constitute a call to rewrite history.

Complex messages can be communicated in historic site interpretation, though it requires a structured learning framework to the visit, more time than a ten-minute browse, a warm but not hot day (in the absence of undercover space for groups), and face-to-face staff. That these conditions are difficult to realise at the cottage makes the achievement of education programs for school students a triumph. 'How famous would you be if people wanted to make a museum out of your mum and dad's house in your honour?' is one way of introducing the awkward history of the cottage, and leads to discussion of Captain James Cook's heroisation in Australia.[61] It is harder to present such ideas in a few minutes to individuals or groups in the tiny cottage rooms, and almost impossible to communicate to non-English-speaking visitors on bus tours. As Vanessa Collinridge, journalist and presenter of a 2007 BBC television program on Captain Cook asked in an astonished tone as she gazed at the cottage, 'Why would anyone want to visit Captain Cook's father's house?'[62] The answer can be explained following the ideas of the Statement of Significance, but a generic interpretation has evolved to avoid the specificity of the Cooks. And despite all, Captain-Cook lives on, incarnate in the cottage walls and furnishings.

Today the cottage is rationalised by its manager as a representation of and tribute to the rural English who emigrated to Australia, willingly or unwillingly, via an authentic domestic setting.[63] It must be said that not all the guides subscribe to this line, and nor do the advertising brochures. Additional items have been added to the rooms without any overall furnishing plan: some, like the tall case clock, are plausible; others, like the mahogany-framed, late eighteenth-century mirror, are not. In practice, the numinous spirit of Captain-Cook continues to permeate the marketing perception, feeding and feeding off the desire of visitors to believe. Thus the application of late twentieth-century professionalism clashes with popular tourism as the métier of the cottage in the twenty-first century, bolstered by Captain-Cook habitude (Fig. 9).

A 2004 survey of visitors and non-visitors indicates the span of interests, assessed from a marketing point of view, in which both Captain James Cook and Captain-Cook are assumed, almost unmentioned, elements of the site.[64] It shows the usual characteristics of heritage tourism demography: 65 per cent female; 52 per cent aged 35–54; 37 per cent with university and higher degrees; 80 per cent in social groups of 2–5 others; 47 per cent visiting with no children; 45 per cent living in Melbourne and Victoria. Three quarters of visitors chose in almost equal proportions the options explaining their motivation as curiosity to see the cottage, interest in history and showing it to the children.[65] Asked what improvements they would like to see, the top recommendation was 'videos and interactive displays'.

In this vein, dress-up costumes, a photo-stand to add an eighteenth-century body to the visitor's face, and a soundscape featuring an invented visit home by the young Cook, envisioned as having newly joined the Navy, were introduced to the cottage in 2007 (Fig. 10) The audio presents the voices of Mrs Cook and her daughter discussing health and remedies; Mr Cook returning from the fields and taking off his boots; and (surely in a gesture to Hermon Gill) the doorstep-boot-ringing arrival of a young man announcing, 'It is I, Mother, returning to visit', inducing Mrs Cook to muse that he could be famous one day. The concept is careful in its gesture to facts, while presenting intelligible Yorkshire voices to humanise the room settings with impressions of eighteenth-century life. The guides report it is well-received by visitors, who further express satisfaction by posting photos of their children peeping through the photo-stand on the website Flickr.

courtesy Linda Young

Three managerial moments in the cottage's career in Melbourne — Grimwade's gift in 1933–34; the National Trust's revision in 1976–78; and Melbourne City Council's CMP in 1993 — mark turning points in approaches to authenticity. Proffered to audiences of visitors, that is, in the consciousness of spectacle, the first two can be judged to have been in good faith. The authors of the reliquary and positivist historical presentations knew what they were doing, and why. But gagged by the discursive reflexivity of the 1993 statement of significance, which acknowledged neither Captain James Cook nor Captain-Cook, the cottage has been in managerial limbo and driven into the bad faith of simultaneously denying and not-denying an authentic connection to the hero.

Does it matter? Among the most problematic elements in the business of historic site preservation and interpretation is praxis: heritage practitioners know it is impossible to re-create the past, yet it is constantly attempted. Guru of authenticity, David Lowenthal, offers modern heritage insights into this topic: '1. The past is gone and irretrievable; 2. It nonetheless remains vital and essential for our well-being; 3. We cannot avoid changing its residues, especially when trying not to'.[67] I will here step away from the detached perch of scholarship to take responsibility for participating in the construction of 'heritage' myself. We do our job by working with the objects that have passed down to us, on the basis of (what we hope is) reliable knowledge and systematic method, informed by consciousness of contests in public cultures. The varying products of this ideal are visible in photos of museum installations over the years. But neither perspective really acknowledges the role of public faith in numinous relics. I suggest it would be acting in good faith for contemporary management of the cottage to engage with this element of what we might as well call magic.

As it happens, to do so would coincide adroitly with a marketing orientation on the part of cottage management by acknowledging and providing the kind of visitor experiences that the market wants. At the same time, the professional standards of heritage, backed by historical evidence as gathered and interpreted by researchers including myself, can be maintained as the context of the magic, perhaps with a multimedia intervention addressing the significance of Captain James Cook and Captain-Cook. It is not possible to reconcile the dichotomies of authenticity that shape the cottage: the eighteenth-century reliquary reality and the 1930s reconstruction reality as it survives 70 years later. But by honouring the presentations of past and present and acknowledging public taste, we can act in good faith.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

2 Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism, Sage, London, 1995, pp. 5–6; Bruce Meyer, Heroes: The Champions of our Literary Imagination, Harper Collins, Toronto, 2007, pp. 5–11.

3 See, for example, Inara Walden, 'Cook's Cottage: National treasure or cultural oddity?', Public History Review, vol. 3, 1994, 120–9; Tony Horwitz, Into the Blue: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2002; Jeff Sparrow & Jill Sparrow, 'Contesting the Captain', Radical Melbourne 2: The Enemy Within, Vulgar Press, Melbourne, 2004; Glyndwr Williams, '"As befits our age, there are no more heroes": Reassessing Captain Cook', in Glyndwr Williams (ed.), Captain Cook: Explorations and Reassessments, Boydell Press, Woodbridge UK, 2007.

4 Jillian Robertson, The Captain Cook Myth, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1981, p. 1.

5 Chris Healy, From the Ruins of Colonialism: History as Social Memory, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1997, pp. 17–37.

6 McCubbin, 'Cooked to perfection' (pp. 40–5).

7 It has an excellent website: www.captcook-ne.co.uk.

8 The full caption is 'South East View of a House at Great Ayton which was Built by Capt. Cook's Father which House He Sold previous to His Going to Live at Redcar', reattributed from Samuel Grimm to George Cuit by Cliff Thornton, 'Scenes in 18th century Cleveland drawn by George Cuit, 1743–1818', Cleveland and Teeside Local History Society Bulletin, Winter, 2007, n.p. The drawing is illustration no. 41 in the Gott Collection (Yorkshire views), Wakefield Art Gallery. It was first identified for its Australian significance in Robert Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage, Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne: Conservation Management Plan', 1993, vol. 1, p. 8.

9 Rudiger Joppien & Bernard Smith, The Art of Captain Cook's Voyages, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1985–88, vol. 2, p. 200.

10 Now in the State Library of NSW, catalogued as a 'ditty box': item DR2.

11 It had been occupied for 20 years up to 1929 by the Simpson family, according to two children of the family who visited the cottage in Melbourne in 2000: Australian, 27 October 2000, p. 6; Age, 27 October 2000, p. 5.

12 Joyce Dixon, History under the Hammer: Why did the Dixon Family Sell Captain Cook's Cottage to Australia?, North York Moors Historical Society, York, 1996, pp. 4–5.

13 Hermon Gill, Captain Cook's Cottage: The History of Cook's Cottage and Voyages of Captain James Cook, Melbourne City Council, Melbourne, 1957, pp. 8–12.

14 Dixon, History under the Hammer, p. 8.

15 Brierley, Rutherford & Syme, 'Plans of Cooks' Cottage, Great Ayton, 1933', State Library of Victoria (SLV): H6128. Specification in Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP', vol. 2, item 7.3.3, pp. 112–17.

16 North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO) Deed no. BC-21-35, 16.5.1772: Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP': vol. 1, p. 7. The Dixons and the Simpsons referred to the entire building as one house.

17 It was first so interpreted by the Reverend George Young, Life and Voyages of Captain James Cook, Whittaker, Treacher & Co., 1836, London, pp. 9–10.

18 Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, Houses of the North York Moors, HMSO, London, 1987, p. 105.

19 When the cottage was reconstructed in Fitzroy Gardens, it was reoriented 90 degrees from the original. Thus the through passage and the second half of the house were at the west end, but are now the south end. This paper refers to the current orientation.

20 Unnumbered photo, 'Captain Cook's Cottage, Great Ayton', by Harold Hood FRPS, n.d., in the collection of Captain Cook Birthplace Museum, Middlesborough Council: www.captcook-ne.co.uk/ccne/exhibits/cotayton/cotayton.jpg (accessed 19 November 2007). The same collection contains another photo dated 1920s, 'Cook's father's house, Great Ayton': www.captcook-ne.co.uk/ccne/gallery/gallery6.htm (accessed 30 June 2008).

21 Many unsourced photos in Grimwade Papers, Newspaper Cuttings 1933–34, Series 15/8, University of Melbourne Archives. A grown-up Simpson child explained the move from the cottage as due to it not being big enough for a family of 11 — evidently because the road widening was about to demolish half of it: Australian, 27 October 2000, p. 6; Age, 27 October 2000, p. 5.

22 Specification, p. 3, in Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP': vol. 2, p. 114.

23 McCubbin, 'Cooked to perfection', p. 40.

24 Salvador Munoz-Vinas, Contemporary Theory of Conservation, Elsevier, Oxford, 2005, p. 94.

25 David Phillips, Exhibiting Authenticity, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1997, pp. 42–3.

27 See Robert N Bellah, 'Civil religion in America', Dedalus, vol. 96, no. 1, 1967, 1–21.

28 Peter Howard, Heritage: Management, Interpretation, Identity, Continuum, London, 2003, p. 227.

29 Auction flyer (photocopy), National Trust (Victoria) files: 1264.

30 Gill, Captain Cook's Cottage, p. 13.

31 KS Inglis, The Australian Colonists, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1974, pp. 242–3.

32 Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage, Routledge, London, 2006, pp. 29–30.

33 Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1999, pp. 13–15.

34 No evidence available in Australia explains on what basis the saved portion of the house is ascribed to the Cook family. The oldest documentary source is the sale in 1772, recording that it was owned by three individuals, one of them being the senior James Cook; see Note 16.

35 Eric Mercer, English Vernacular Houses: A Study of Traditional Farmhouses and Cottages (Royal Commission on Historical Monuments England), HMSO, London, 1975, pp. 50, 59.

36 BRS Specification, in Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP': vol. 2, p. 114.

37 Steven Lewis, 'The man who collected ordinary life', York Press, 19 April 2008, www.yorkpress.co.uk/news/2209976.m5ec/?from=ec&to=2209976&l=the_man_who_collected_ordinary_life(accessed 30 June 2008).

38 John P Rogan, 'Report and recommendations relating to Captain Cook's Cottage, Melbourne', 1976: National Trust (Victoria) file B1264/4; John Rogan, 'The furnishing of Cook's Cottage' in Cook's Cottage, National Trust (Victoria), Melbourne, 1978, p. 17.

39 Captain Cook's family tree: www.captaincooksociety.com/ccsu67.htm, accessed 2 July 2008. Cradles infest the bedrooms of re-created domestic scenes, regardless of period represented.

40 See www.dickensmuseum.com/; www.drjohnsonshouse.org/history.htm; accessed 30 July 2008.

41 Letter from Linton (Agent General) to Charles Thornton (antiques dealer), 29 August 1933: Grimwade Papers Series 3, Box 4, Folder 3/3.

42 Christopher Gilbert, English Vernacular Furniture 1750–1900, Yale University Press, New Haven CT, 1991, pp. 31–40.

43 Letters from Grimwade to the Town Clerk and the Premier, 1935–37: Grimwade Papers, Series 3, Box 4, Folder 3/1, Melbourne University Archives.

44 Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP': vol. 1, pp. 24–5.

45 'Contents of Cook's Cottage', 17.4.1961: National Trust (Victoria) file B1264/4. Alleged Cook items included a tea caddy (the one now in the State Library of New South Wales?), a pair of boots (now returned to private owner), and manuscript items.

46 Fully presented in a new booklet, Cook's Cottage, 1978, and contrasting radically with the first booklet by Hermon Gill, Captain Cook's Cottage, 1934, re-issued in 1957 and 1971.

47 Miles Lewis & Alison Blake, 'Captain Cook's Cottage', Urban Conservation Working Papers no. 25, Faculty of Architecture & Building, University of Melbourne, 1977; Cook's Cottage, 1978.

48 Lewis & Blake, 1977, p. 5. Also, 'The Cooks and the cottage' in Cook's Cottage [new edition of Cottage booklet, with major revisions], Melbourne City Council, 1978, pp. 8–9.

49 John P Rogan, 'Report and recommendations'.

50 Cook's Cottage, 1978, pp. 17–18.

52 Mary Lewis, 'Captain James Cook, FRS', Cook's Cottage, 1978, pp. 2–7.

53 Article 3, 'Australia ICOMOS guidelines for the conservation of places of cultural significance ("Burra Charter")', Australia ICOMOS Newsletter, vol. 2, no. 3, 1979, n. p. (the first public printing). See Marilyn Truscott & David Young, 'Revising the Burra Charter', Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, vol. 4, 2000, 101–3.

54 Healy, From the Ruins, p. 14

55 Item 5124 on the RNE: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/places/rne/index.html (accessed 10 June 2008). One wonders why representation of Great Ayton vernacular building is significant in Australian heritage.

56 The cottage is not listed in the Victorian Heritage Register beyond mention in the inscription of Fitzroy Gardens in 1999. It is hard to tell whether this reflects the limits of the VHR or doubt about the significance of the cottage.

57 Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP': vol. 1, p. 1.

58 Healy's analysis of the cottage occupies Chapter 1 in his book, From the Ruins of Colonialism: History as Social Memory, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1997.

59 Sands, 'Cooks' Cottage: CMP': vol. 1, p. 79.

60 See www.bundabergonthe.net/hinkler/hinkler_house.htm (accessed 15 June 2008). The ur-specimen of a relocated house is the Santa Casa of the Virgin Mary, flown by angels from Nazareth to Croatia in 1291, and again in 1294 to Loreto in Italy. See: Catholic Encyclopedia, www.newadvent.org/cathen/13454b.htm (accessed 26 June 2008).

61 Discussions with Joan O'Grady, Consultation and Interpretation Coordinator, City of Melbourne, July 2008.

62 Captain Cook: Obsession and Discovery, ABC DVD, 2007.

63 Discussions with Christine Gibbins, then-manager of the cottage, November 2006.

64 Cooks' Cottage Visitation 2004, City of Melbourne.

65 Non-visitors explained, in much smaller proportions, that they hadn't visited because they'd been there before, it didn't look very interesting, they hadn't enough time, and no special reason; just one said he didn't visit 'because it wasn't Cook's house but his parents'.

66 MacCannell, The Tourist, p. 104.

67 David Lowenthal, 'Authenticities past and present', CRM: The Journal Of Heritage Stewardship, vol. 5, no. 1, Winter, 2008, p. 4.