In this article I discuss three groups of archival records held by the Australian War Memorial: firstly, some records put to immediate use after the First World War for the writing of Australia's official war history, secondly, a collection of private records acquired by the Memorial in the 1920s and 1930s and, lastly, a large quantity of administrative (as distinct from combat-related) records, acquired in 1931.

The first group had an immediate and lasting impact on understanding of Australia and the war. The second was largely unused until the late 1960s, when it became central to the work of historians exploring new historical approaches. The potential of the last group is only now being realised.

I seek to join the creation of the records with their acquisition and use (or non-use) as archives. I try to see past their content to explore their histories, and in so doing I hope to contribute to an enlivened discussion of the creation and use of museum, library and archives collections.

____________________________________________________

In the interests of the national history of Australia and in order that Australia may have the control of her own historical records, especially in so far as they relate to the present war, the Australian War Records Section has been formed, and is located at the Public Record Office, Chancery Lane, London W.C.2.[1]

So begins a document that marks the start of Australia's efforts to collect the records of war. It was a memorandum issued from London in July 1917 to all commanding officers in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) notifying them of their responsibilities to ensure that records of their units were properly kept and preserved. It was in the interests of the national history of Australia that a collecting facility had been established. It would ensure that Australia had control of her own historical records. The records would form an 'Australian National Collection' from which the history of the war would be written. There was at the time no Australian national record office, so Australia's official military records were being passed to British authorities. But the establishment in May 1917 of the Australian War Records Section (AWRS) represents a moment when a few influential Australians overseas, especially Charles Bean, Australia's official war correspondent and later official historian, imagined an 'Australia' which by its efforts and sacrifices was at last making its own history, and which therefore had earned the right to keep its own records. It was a powerful mix: nationalism, historical consciousness and an obligation to the dead.[2]

Before records exist, there is a moment, according to some archivists, when someone has to decide that an event or a thought is worth recording. Of the myriad events that occur every day, some are recorded but most are not. To borrow from the Book of Genesis, the event — like the earth at the moment of creation — is 'without form, and void' until it is imagined into being by the record creator, who then uses whatever method might be appropriate for transmission (an entry in a register, a report, a letter, a diary entry, an email, a photograph or whatever). The events chosen for recording are socially and culturally determined, and the technology used to record the event can help to shape it and the way it is understood in the future. Furthermore, the process by which a record makes it into an archive, and how it is arranged, stored, made accessible and used, all help to 'create' the record and add meaning to it. The postmodern archivist seeks to understand these processes, and to make transparent his or her active role in them.[3]

Such an archivist is open to the idea that a record can mean various things to various people, and in this he or she joins with museum curators and historians in reading records and artefacts around and against the intentions of their creators. (Most museum curators know, too, that visitors will often make their own meanings out of objects on display, whatever we say about them.) If we allow that the material evidence of the past is transmitted to us by a variety of non-neutral, culturally determined processes, we will naturally all be interested in the people who create, keep and use that evidence. Their lives, their backgrounds, their choices, their acts of imagination and creativity are part of the story.[4]

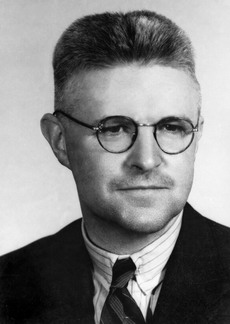

All of this suggests that the history of collecting and collectors is worthy of study, something that the patient reader probably already knew.[5] But my purpose here is to focus on a few people who have imagined archival collections into being, starting from nothing. I want to look at how these people conceived of the need to collect and preserve records, how they achieved that, how they envisaged the collections' future use and how the collections have actually been used. I have here three collection history sketches to offer, all concerning the experience of Australians at war, and all further linked by the involvement of a circle of people at the centre of which was John Treloar, long-time director of the Australian War Memorial and one of Australia's great collectors.

photograph by Edward Cranstone

Australian War Memorial, negative number 005915

The chief imaginer at this point was Charles Bean, but turning dreams into reality needed someone of the calibre of John Treloar, the 23-year-old army officer selected as officer-in-charge of the AWRS.[6] Treloar had been a military clerk with the Defence Department before the war and had enlisted in the AIF in August 1914, as soon as the war broke out. Hardworking and ambitious, he served on Gallipoli, in the Middle East and on the Western Front in a variety of administrative positions that gained him a thorough knowledge of military recordkeeping. He was not an imaginative man in the usual sense; nor was he a visionary or a lobbyist or a social networker, still less an activist or radical. But if there could be such a thing as 'administrative imagination', he had it. He had a way of swinging between the detail and the bigger picture of any given situation, of thinking around a problem to find a range of solutions, and of understanding the people and systems within which he worked. As an example, the memorandum to commanding officers (quoted above) was largely his work, although it was amended here and there by Bean and others. It carries all the information and detail that its recipients needed and nothing they didn't. He had it printed as a small pamphlet, compact and handy, rather than on the usual typed foolscap sheets which he knew could be overlooked or lost by busy commanding officers. This typified his perception and foresight.

Out of Treloar's good state school education in Victoria had emerged an idea for him of an 'Australia' worthy of the best he could give. What he wanted, he told Charles Bean a little later, was 'to do something really worthwhile for Australia'. And it pleased him that the Public Record Office (PRO) in London, which held the 'records of the Motherland from the earliest times', had commenced the task of 'bringing together the records of the events in which the daughter dominion of Australia realised her nationhood'.[7] As a result of Treloar's efforts in mid-1917, records started pouring into his two rooms at the PRO and later he moved the section to larger premises in Westminster, opposite AIF Administrative Headquarters in Horseferry Road. The records he was soliciting constituted a large part of the records later used by Charles Bean to write his volumes of Australia's First World War official history. Not Bean's own diaries, notes, correspondence, and records of interviews, vital though that material was, but the records created by Australian military units and formations: their war diaries and administrative records. On a 'careful estimation', Bean later remarked, the total of these ran to 21,500,000 foolscap sheets.[8]

An army in the field generates a lot of paper, but the AWRS was the first agency enforcing standards for the way Australian units created, kept and disposed of records. Before that, units did keep war diaries — which consist of a day-by-day summary of events and activities, supplemented by a variety of appendices — but the diaries were passed to British authorities. Units might or might not have kept a duplicate, and the duplicate often did not include the crucial appendices. The section was established with the agreement that Australia could keep the originals of its own war diaries if copies were left with the British.

Treloar believed that the best way of convincing officers to improve the war diaries was by demonstrating that they were valued. They were not placed in some 'dusty corner' at Base and promptly forgotten. They would form an 'accurate record' on which the history of the war would be written. 'Remember!' he declared. 'A well-kept diary is the surest pledge to future recognition ... Attach every interesting paper. It is the best way of preserving it for the Regiment and for Australia.' His staff interviewed commanding officers personally and had special stationery printed for the war diaries so as to impose uniformity. With a gimlet eye Treloar read the diaries as they came in, and handed out praise and constructive criticism as appropriate. Exact locations, times, distances and positions in which actions occurred were demanded: 'daylight' and 'a little further' were not acceptable. Flanking units had to be referred to by their exact titles. Proper map references were necessary, as were regular statements of the strength of the unit and relevant information about the enemy. Maps and reports on operations had to be attached as appendices. Routine as well as outstanding matters were worth noting. And surely, he thought, no unit would be content to leave this as the only permanent record of a 'gallant fight':

23/7/1916: took part in an attack. Captured all objectives.'Now what could an historian do with that?' he reflected later. That date, 23 July 1916, happened to be the first day of the battle at Pozières, one of the most dreadful of all the battles the Australians endured. Treloar's instructions and interventions were designed to improve the standard of recordkeeping in a way that would gladden the heart of a records manager today.[9]

Not just war diaries, but maps, aerial photographs and a unit's own administrative records and correspondence had now to be sent to Treloar's section. The administrative correspondence generated by units often contained important evidence not contained in war diaries. But by late in the war, the sheer complexity and bulk of the records was a problem. How could the historian and a small staff make sense of it all? Treloar's solution in relation to the war diaries was to prepare précis of them, placing 'all information of value in them in a convenient form for reference by the historian'. The unit correspondence was arranged using a complex system, devised by Treloar and his staff, that combined subject classification with classification by unit. Correspondence thought not to be of use to the historian was discarded at this point.[10]

This brings us close to the end of the war. The AWRS was huge now. It was collecting and organising all kinds of other material, not just documentary records, but also photographs, film, objects, art, maps and published material. But by mid-1919 all but a small group of the several hundred staff were demobilised; in Australia the collection and the remaining staff formed the core of the Australian War Museum (later Memorial) in Melbourne. But even as this new and much more complex organisation sought to establish itself, work on the records continued, for the official historian, Charles Bean, needed them. It was now horribly apparent that the best mode of access to the documentary records was not primarily subject, after all, but chronology. So, starting in the early 1920s and after considerable negotiation between the Memorial and the official historian's staff, a new, artificial arrangement was imposed on the records by the Memorial's staff. It consisted of the most relevant of the subject-classified files, plus spare copies of war diaries and the war diary précis. The chronology was broken up into predetermined periods of the war. This is the 21,500,000 sheets, or 119 metres of records, that Bean used as the backbone of his Western Front volumes.

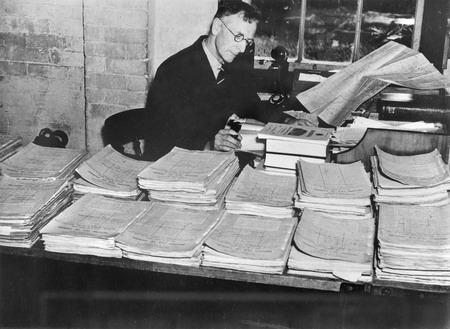

The work of classification was much slower because whereas in London it had been done by hundreds of soldiers awaiting demobilisation, now in Melbourne the Memorial could spare only a handful of staff for the task. In fact the work continued well into the 1930s, with the historian, as he later recalled, 'treading on the heels' of the classifiers. The records were known for many years as the 'operations files', or more recently as official records series AWM26. The idea of the arrangement is that all the records relevant to a particular period could be set out on a tabletop to reconstruct the actual layout of the formations engaged in combat at that moment. The famous photograph of Bean at work at Victoria Barracks in Sydney in 1935 shows him working in just this way. But as one of the Memorial's archivists remarked years later, this could either be simple if one understands the events and the records as well as did Bean and his staff, or complicated if one does not. Bean himself turned over 10,000 sheets of paper related to just one day's fighting and the preparations for it.[11]

Mention of private papers brings forward my second sketch. In 1920 John Treloar was appointed director of the Australian War Museum, and he pushed on with building the collection. While a massive effort had gone into acquiring official military records, Treloar also wanted personal records created by individuals. At first he acted upon an interest he had in chaplains' records. In late 1921 he wrote to dozens of ex-AIF chaplains asking them to submit to the Memorial accounts of their experiences. Records being handed down to historians, he told them, were failing to adequately provide for the 'intimate and personal record of the work of chaplains', and for the 'spiritual life' of the 'rank and file' soldier. Former chaplains were being asked to generate historic records retrospectively, in effect. It was an odd request but the response was good. Quite a few people sent in short narratives, often in the form of a letter back to Treloar. They are still there, of course, for anyone to use but they are isolated from the administrative files that document their origins.[14]

This collecting effort was just a curtain-raiser. In 1926, a member of Bean's staff, Arthur Bazley, suggested to Treloar that the Memorial write to as many families of soldiers who had died as it could, asking them to donate any private letters or diaries that had been created by their relatives. In the course of his work, Bazley had become aware that there were many personal records still in the hands of veterans and families. Treloar agreed, and ultimately nearly five-and-a-half thousand families and, later, returned men were contacted in person. What the Memorial wanted, they were told, were records of the 'thoughts, hopes and fears, which were then uppermost in the mind[s]' of soldiers and sailors. Treloar thought that the records might 'permit of a psychological study' of the men of the AIF. The intense period of collecting lasted only four or five years, but in that time each and every prospective donation was tactfully and tirelessly followed up by Treloar. He was trying to persuade people to part with their most precious possessions. Many letters might pass and back and forth between the Memorial and a donor, often resulting in a donation or loan of records, but in other cases, nothing. The only other institution which had been actively collecting soldiers' personal records, although on a more limited scale, was the Mitchell Library in Sydney.[15]

In recent decades the huge increase in the amount of recorded information has forced archivists to develop complex strategies to decide what material to keep for long-term use. But Treloar belongs to a generation of collectors who wanted to vacuum up as many records as possible. He and Bazley boldly imagined a use for them that historians had not yet imagined. It was highly unusual for anyone to be thinking in terms of psychological, emotional or spiritual approaches to history. This was decades before anyone was talking about 'history from below'. People's intimate lives, especially ordinary people's intimate lives, were not then usually considered the stuff of Australian history. Charles Bean read all of the private records available to him, but rarely refers to them overtly in his text and his history was built around the operations files and his own records. He knew what went on in the mind of a soldier, but the work he produced mainly told what soldiers did, rather than what they felt.

Treloar died in 1952. The private records were still largely an unknown source when Bill Gammage stumbled upon them in 1960 and they ignited his desire to write an 'emotional history of the AIF', published in 1974 as The Broken Years. Gammage described the book as an exploration of what 'some soldiers thought and felt during the war': a fulfilment at last of the hopes of those founding collectors. It happened that Arthur Bazley was alive still in the period that Gammage undertook the research and the old man was able to help this young student from a later age — who had never seen a shot fired in anger and never expected to — take the dead of the Great War from 'memory to history'.[16]

Australian War Memorial, negative number 127937

Embarking on my third sketch brings to mind that phrase — 'dusty archives' — loved by journalists, resented by archivists. But unfortunately some of the records I'm thinking of this time really do retain some dirt and it is not dirt from the battlefield, which we might forgive, but our own local Australian dirt.

From its inception, the Memorial, and Treloar in particular, was interested in the fate not just of combat-related records, but also of any and all records related to the Australian experience of war. This included records of 'historical value' created by Commonwealth government departments. 'A young dominion like Australia', Treloar told Bean, rehearsing the stubbornness he would show on this issue in later years, 'should be able to hand down to posterity complete records ...' In an early coup, the Memorial secured the agreement of the Prime Minister that departmental records be passed to the Memorial, but in the event, little came of it. The exception, and it is a significant one, is that in 1931 the Department of Defence did transfer to the Memorial administrative records — as opposed to combat-related records — created by AIF headquarters and depots in Britain and the Middle East. It is significant because a large and complex group of records was involved, and because persistence on the part of Treloar and his staff probably saved many of the records from being destroyed by a 'Correspondence Destruction Committee' operating in the Department of Defence in the 1920s.[18] The records covered include postings, pay and promotions, medical administration, finance, transport and supply, discipline, courts martial, prisoners of war, war graves, education, demobilisation and return to Australia. Anything one can think of, in short, to do with the administration of an army in the field. Not everything on offer was taken, however. The records were appraised by Tasman Heyes, Treloar's deputy. Heyes's report to Treloar shows us a records expert deeply interested in and enjoying his task. But Heyes had to grapple with a problem familiar to archivists today: how to deal with personal case files. Heyes believed that case files were of little historical significance other than from the point of view of 'statistics and rulings'. These, he thought, could be gleaned from 'general' files. His solution seems to have been that where a group of administrative records included a mix of case files and general files, these were to be acquired. Groups consisting solely of personal files were apparently not acquired. Still, a vast quantity of records, hundreds of metres, was acquired.[19]

The records sat in storage for many years, firstly in Melbourne, later in Canberra. There were many demands upon the Memorial's resources in the lead-up to and aftermath of the Second World War. Space had to be found for the collections associated with the new war and, in 1947, in a move that shows that even Treloar was prepared to sacrifice records he believed to be of a 'routine nature' in order to save space, he had his staff carefully reappraise some of the First AIF administrative records, and as a result some destruction took place within at least one series. The records then remained untouched and, in some cases, stored in crates open to environmental hazards including dirt. In the late 1950s, a low point in the Memorial's history, they were subject to a much harsher reappraisal, again probably to create more space. This resulted in the destruction of over 95 per cent of the records in some series. Tantalisingly, lists of some of the destroyed files remain and they reveal some unfathomable decision-making on what to retain or destroy. What was left is still very substantial, but the existence of the records was practically unknown outside the Memorial, and even the staff seemed uninterested and baffled by them. Heyes had imagined that the records would be of interest to the official historians and that, furthermore, the 'administrative side of the AIF', which in his day was well-known, would not last and in the future, the records 'must form the basis of any reliable [historical] work'.[20]

It took a long time for this to happen. In the 1980s and 1990s, the records were gradually awakened from their long sleep. Some record series within this group are not fully described at the item level, meaning that the powerful electronic keyword searches that are possible within AWM26 and the private records are not always possible here. Still, the potential richness of these records in terms of personal stories, family history and administrative history is now apparent. Several books have been published, for instance, on the activities of Australian military police in the First World War, drawing upon the records of the Assistant Provost Marshal. In the late 1990s two doctoral candidates from the Australian Defence Force Academy, Bruce Faraday and Ross Mallett, drew upon some series — hampered, unfortunately, by the culling — to write about the organisational and administrative life of the AIF. In his introduction Faraday identified a general lack of interest among military writers in the administration of armies. He quotes Archibald Wavell's famous observation that for every ten students who can tell you how Blenheim was won, only one has any knowledge of the administrative preparations which made the march to Blenheim possible.[21]

Charles Bean's history was a combat-related, soldier's-eye view of the war. This was the history he imagined he would write, and the records he needed for it were imagined, created and arranged so as to allow him to write that story. The records he used for his Western Front volumes — AWM26 — were arranged for him. Accordingly, every later historian has had to work within that framework: what was not selected for his immediate use might be quite hard to recover now.[22] His history has been so dominant that it has held back other modes of history, and other types of records, from finding their moment. As we have seen, Arthur Bazley and John Treloar imagined that there would be a need for a psychological study of the first AIF; but that was not part of Bean's main intention and it had to wait for a later era. We are lucky that when it happened, Bill Gammage could gather from one of the collectors — Bazley — that 'priceless gift', as Gammage called it, of a sense of what the first AIF was like. Where we are not lucky is that the personal records of civilians at home were ignored in the Memorial's appeal. The letters from a soldier at the front were sought, but not the letters to him from home. What a loss that is.

Finally, Treloar and Heyes imagined that the administrative record of the AIF would one day be needed; but again Bean touches on this only briefly and now the living link to the records has been broken. Circumstances led to their immediate neglect; and because few historians have been interested, it is much harder for archivists to gain a better understanding of the records. And while we are thinking of record losses, we might wonder, with the benefit of hindsight, why the Memorial valued soldiers' personal letters and diaries, but not the individual case files used to administer aspects of their official life in the AIF.[23]

So can it be said that a record is a fixed and static thing, simple to describe and use? Or that archivists are merely neutral guardians of inherited records? Perhaps not. It seems that records are best understood and managed if we study processes that begin before a record is created; which interact with one another and carry on through its lifespan; and which don't end even if the record is destroyed. Australian archivists have defined this concept and labelled it the 'records continuum', although, sadly, their elucidations of it can be impenetrable to a layperson. The idea that collections have histories which are enacted both before and after they enter a museum is not likely to be news to museum curators, and historians are accustomed to reading evidence against the grain — of finding uses for records quite outside the intentions of the creators. However, few historians know very much about how archives and museum collections are acquired and managed, or how these processes shape the nature of the evidence. Historians and other users of collections expect to learn from the content of a collection but don't (consciously at least) expect the collection as a whole to have its own independent life, its own biography, its own message. My sketches help to illustrate this point: that what we desire of a collection, how we love it, use it, neglect it, forget about it and rediscover it, tells us something not just about the external world, but also about ourselves.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

2 Michael Piggott, 'The Australian War Records Section and its aftermath, 1917–1925', Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 18, no. 2, December 1980, 41–50; Michael McKernan, Here Is Their Spirit: A History of the Australian War Memorial 1917–1990, Univerity of Queensland Press and the Australian War Memorial, St Lucia, 1991, chapter 2.

3 Much has been written on this, but for recent work see especially: Sue McKemmish, Barbara Reed and Michael Piggott, 'The archives', in Sue McKemmish et al. (eds), Archives: Recordkeeping in Society, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, 2005; and Tom Nesmith, 'Reopening archives: Bringing new contextualities into archival theory and practice', Archivaria, vol. 60, Fall 2005, 259–74.

4 Michael Piggott, 'Human behavior and the making of archives and records', Archives & Social Studies: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, vol. 1, no. 0, February 2007 (forthcoming).

5 But in general, see for example: Libby Robin, 'Weird and wonderful: The first objects in the National Historical Collection', reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 1, no. 2, http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_1_no_2/papers/weird_and_wonderful/; Joanna Sassoon, 'Phantoms of remembrance: Libraries and archives as "collective memory"', Public History Review, vol. 10, 2003, 40–60; and Craig Wilcox, 'Redcoat dreaming', ALR: The Australian Literary Review, vol. 1, issue 4, December 2006, 8–9.

6 On Bean, see KS Inglis, 'Bean, Charles Edwin Woodrow (1879–1968)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 7, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1979, pp. 226–9, online at: www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A070225b.htm?hilite=bean. On Treloar, see Denis Winter, 'Treloar, John Linton (1894–1952)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 12, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1990, pp. 256–7, online at: www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A120287b.htm?hilite=treloar.

7 Letter, Treloar to Bean, 9 May 1919, AWM38: 3DRL 6673/362; John Treloar, 'Australia's war records: How they were collected, what will be done with them', draft of an article for Life magazine, about 1920, AWM93: 20/1192. All archival references are to records held by the Australian War Memorial.

8 CEW Bean, 'The writing of the Australian official history of the great war: Sources, methods and some conclusions', Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 24, part 2, 1938, p. 97.

9 Treloar, draft of article for Life magazine; AIF, Memorandum to Commanding Officers [pp. 10–11], [p. 14]; Australian Imperial Force, Memorandum to Officers Commanding: Historical Records, Australian War Records Section, London, 31 December 1917, p. 2.

10 'Report on the work of the Australian War Records Section from May 1917 to September 1918 by the Officer-in-Charge', AWM224: MSS553 part 1, p. 18.

11 Bean, 'The writing of the Australian official history', pp. 97–8; Bruce Harding, 'Official primary sources in the Library of the Australian War Memorial', March 1973, AWM315: 535/002/001.

12 PA Pedersen, Monash as Military Commander, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985.

13 Les Carlyon, The Great War, Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney, 2006. Note that until the Archives Act 1983 came into effect, the Memorial made its own decisions about access to these records and this meant that the records were effectively 'closed'. Thanks to Bill Gammage for reminding me of this point.

14 Circular letter, Treloar to chaplains, late 1921, AWM93: 12/5/20. For subsequent developments see AWM93: 12/5/18 and AWM93: 12/5/19.

15 Quotes from the letter of appeal are taken from the first that was sent out, to Violet Gibbins, on 12 March 1927. See AWM93: 12/11/1. For a comparison of the collecting efforts of the Memorial and the Mitchell Library, see Anne-Marie Condé, 'Capturing the records of war: Collecting at the Mitchell Library and the Australian War Memorial', Australian Historical Studies, vol. 125, April 2005, 134–52. On the significance the records had for the donors, see Anne-Marie Condé, 'The symbolic significance of archives: A discussion', Archives and Manuscripts vol. 33, no. 2, November 2005, 92–108.

16 Bill Gammage, The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1975, pp. xiii, 34.

17 See especially Peter Stanley, Tarakan: An Australian Tragedy, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997; and Peter Stanley, Quinn's Post, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005. More generally, see Alistair Thomson, 'Anzac stories: Using personal testimony in war history', War & Society, vol. 25, no. 2, October 2006, pp. 1–21.

18 Letter, Treloar to Bean 1922, AWM93: 12/5/208/1; Eric Andrews, The Department of Defence, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2001, pp. 69–70.

19 The records series in question are AWM10 to AWM23, except AWM16, which was transferred later, in 1935. See Tasman Heyes, 'Report on test check of overseas AIF registries now stored at Base Records Office, Melbourne', 5 March 1931, AWM93: 12/5/208/6; 671 cases of records were acquired in two groups on 26 March and 21 April 1931.

20 Heyes, 'Report on test check' pp. 2–3.

21 By 1982 they had been individually registered as series and were listed in a published guide for the first time that year. The books drawing on provost records are: Glenn Wahlert, The Other Enemy? A History of the Australian Military Police, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1999; Geoffrey Barr, Beyond the Myth: Australian Military Police 1914–1920, HJ Publications, Canberra, 2005. The theses are: Bruce Faraday, 'Half the battle: The administration and higher organisation of the AIF 1914–1918', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, 1997; and Ross Mallett, 'The interplay between technology, tactics and organisation in the first AIF', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, 1999.

22 Correspondence files not selected for Bean's use eventually formed their own series, AWM25. Combat records from the Gallipoli campaign are also in this series. For a full list of all official records series held by the Memorial, see: www.awm.gov.au/research/guides/appendix2.htm.

23 Bill Gammage, 'Research at the "Old" Memorial', Journal of the Australian War Memorial, no. 19, 1991, 38–9. Much has been done to better describe and house the records, although some series still need more work. On soldiers' personal files, I am thinking here of records documenting cases where a soldier's circumstances required individual treatment, such as his non-military employment, or the return of his overseas dependants. The files now known as soldiers' 'service records', containing the more routine papers such as attestation papers, were retained by the Department of Defence and are now held by the National Archives of Australia. But even the 'service records' have a complex history which would repay further attention.