Built on a private collection of hundreds of thousands of artefacts and antiquities, the National Museum of the American Indian was absorbed nearly twenty years ago into the Smithsonian Institution. It now has three 'facilities', as the Smithsonian puts it, including the Heye Center (named for the private collector) in part of a magnificent former customs building at the southern tip of Manhattan. To dwell on the museum's incomparable inheritance, to show room after room of Mayan murals and Pueblo pottery and little else, would be to see American Indians through ethnographic eyes rather than aesthetic ones, and admire a bygone past rather than engage with a troubled present. This would constitute both professional and political suicide, so the museum aims not merely to document and interpret what it calls Native cultures throughout the Americas but also to support and promote their current expression.

by Michael Kabotie (Navajo, b. 1942), Arizona

silver, turquoise; 7.5 x1.7 cm

It still collects more or less traditional craft pieces and costumes, but it also buys souvenirs made for tourists and fine art made for galleries. A small but representative sample of the fifteen thousand such items collected since 1990 was displayed recently in the Heye Center as Indigenous Motivations. Modest in size and mood, the exhibition barely competed for the attention of the millions who cram into New York's museums each year. But it deserved attention for carrying out an ambitious brief in a difficult space, and for how it interpreted indigenous creativity.

by Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty (Assiniboine/Sioux, b. 1969), North San Juan, California

hide, cotton cloth, glass and brass beads, porcupine quills, ribbon, human hair, commercial leather, shell, metal bells, white sage; 35 x 33 cm

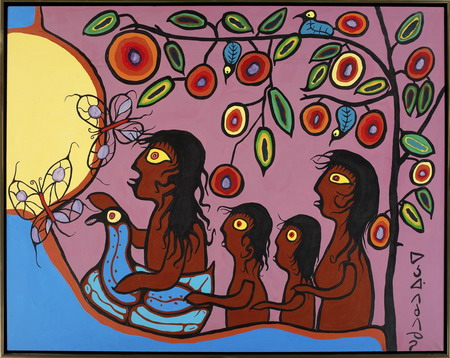

by Norval Morrisseau, (Ojibwe, b. 1931), Thunder Bay, Ontario

acrylic on canvas; 134 x 107 cm

One pause area looked toward a large lime panel proclaiming Art, containing an arresting sculpture, quoting Native artists and showing photographs of them at work, and asserting that their art is both situated in Native experience and as lively and open-minded as any other. Around the panel were marshalled the exhibition's most modern-looking paintings, sculptures and jewellery − anything which would have fitted seamlessly into the collections of art museums of wider remit in the city. The other pause area looked on to the azure Innovation panel, housing a cluster of miniature totem poles made for tourists and an argument that the souvenirs and designer kitchenware at that end of the exhibition were as authentically Native as anything else in the room. Visitors who walked in off the grand customs house foyer had no pause area to brief them, but they were prepared for what many would have seen as the core of the exhibition, indeed of the museum's purpose, by the saffron Tradition panel. Its striking crimson costume from Guatemala drew attention to a statement that tradition allows values to be maintained while its observers adapt to the outside world. Behind this panel were grouped what used to be the stuff of ethnography − masks and pottery, woven baskets and hats.

If most of the objects which the two pause areas and three panels introduced had to be housed in bland, inherited cases, at least those cases were understated and mostly free-standing, making for clear and undistracted viewing. Then again, the encounter with most objects would have been a joy anyway. The richness and mixture of colour in costumes from Guatemala and Ecuador challenged Matisse to do better. Etidlooie Etidlooie's carved Polar Bear (1973) reflected thousands of years of watching and living among creatures who are kindred. Some dilemmas and trials of Native life were evident in Richard Glazer-Danay's tiny diorama Tradition (1983), with its glamorous pink-skinned idol of Progress, or Joe Feddersen's glass sculpture Tire (2003), its design derived not from the customary animal tracks but the tyre marks left by SUVs, or Marcus Amerman's hanging Lucky Blanket (1998), evoking the kitsch of the casinos whose profits some communities live from. Jerry Laktonen's Blue Dream Paddles (2004) updated an antique idiom just as Australian Aboriginal people working on canvas and paper are doing. Some other artworks, like Dan Namingha's canvas Pueblo at Dusk (1987) and Victor Vasquez Temo's The Last Recruitment of 1995 (1997), were Native in subject matter but not in medium or vision. Roger Tsabetsaye's silver coffee pot (1965) and Ronald Senungetuk's cheeseboard and knife (c1980) are classic examples of modern design and had only their labels to suggest a Native origin; beautiful, to be sure, but still seeming out of place despite curatorial argument to the contrary. Perhaps there was too much beauty. Perhaps it's easier to say souvenirs shouldn't be sniffed at when most examples shown were so ingenious and well-made.

by Boyd Owle (Cherokee), North Carolina

Indian Arts and Crafts Board Collection, Department of the Interior, at NMAI

Labels which didn't simply list title, maker, date and dimensions were usually lithe, let creators as well as curators speak, and were always signed. 'I have always considered my artwork as toys', visitors could read Glazer-Danay explaining beneath his Tradition; 'I don't look at my studio as a factory. I go there to have fun all day long ...' Some text, though, in performing the duty of supporting and promoting Native cultures ('Indian art can compete with any art', for example) redundantly offered affirmation rather than information. At other times, more text, or sometimes more than text, was needed to deal with the distance. The comment being made by Richard Seeganna's sculpture Land Claims Dance (1973) was unexplained, likewise the striking similarity in form between the Andean woven hats and military forage caps of two hundred years ago. Nothing enlarged the almost invisibly intricate design carved by Delia Poma de Nunez into a gourd (2002). A subtle soundscape − though not the frenetic infotainment of a video presentation − would have further overcome the shoebox's silent blandness and increased the insulation from the customs house's grandeur.

Still, Indigenous Motivations was a canny, attractive presentation of a whole museum's collecting and interpretive direction. Its argument for taking souvenirs seriously was itself a memorable souvenir for visitors to take home and think over. In juxtaposing craft pieces and art from indigenous people across a continent it offered a range of mediums and visions absent from any exhibition about Aboriginal Australians, or any exhibition of their art, that I've seen.

Then again, the inclusiveness had an uneasy aspect too. A label in Indigenous Motivations let Roger Tsabetsaye speak up for making 'universal art', but his coffee pot appeared among the baskets and moccasins all the same, claiming him and Senungetuk as a capital-N native artists. Maybe, for all I know, they wouldn't mind that; and showing work by anyone who's indigenous as indigenous might provide a broadly useful context. But doesn't it misunderstand some art, just as it would misunderstand Matisse to label him and his paintings Flemish?

Indigenous Motivations can still be glimpsed in website and in published forms, each as informative and crisply designed as the exhibition itself. They should be pondered by anyone thinking of how to sum up their museum's mindset in a small exhibition, or wondering, if they're Australian, whether collecting and exhibiting creativity by every Aboriginal person as Aboriginal is pertinent or, well, patronising.

Craig Wilcox is a historian who lives and writes in Sydney.

|

Institution: |

George Gustav Heye Center, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, New York |

|

Curatorial team: |

Ann McMullen, Bruce Bernstein and Cynthia Chavez (curators), Lindsay Stamm Shapiro (project manager), Rachel Griffin (research assistant), Mark Hirsch (editor) |

|

Design: |

Gerry Breen (designer), Peter Brill (design liaison), Susanna Stieff, Deborah Alden and Sooja Lee (graphic designers), Shelley Uhlir and On The Verge (object mounts) |

|

Exhibition space: |

483 square metres |

|

Venue/dates: |

George Gustav Heye Center, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Bowling Green New York City, 22 July 2006 to 10 June 2007; thereafter on web page |

|

Publication: |

Indigenous Motivations, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington 2006. |

|

Website: |

Jason Wigfield, Cheryl Wilson |