A gathering interest in expatriates — now often referred to as the Australian diaspora — has created a context in which one of our most elusive artists, George Lambert, can be reappraised — or even appraised. The exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia is the first extensive retrospective exhibition since Lambert's death almost 80 years ago. Among the canvases not here — apart from those which have dropped from sight — are those from the Australian War Memorial currently on display in Melbourne. Others have found their way to galleries in Bombay and Chicago, and to the Hermitage. Nonetheless the exhibition is strikingly comprehensive, including major public sculptures brought from Sydney and Geelong.

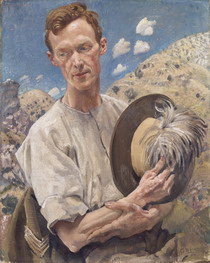

Part of the problem Lambert presents was that he was not so much an Australian artist as a cosmopolitan. Born in 1873 in St Petersburg, some months after his American father died, he was taken first to Germany and then to London by his English mother. When Lambert was 10 they migrated to Australia. Later, the longest phase of his career would be spent in England, when he returned there in 1902 after two years in Paris. There was also a significant period of three or four years as a war artist in the Middle East. Although Lambert spent his last nine years based in Sydney, dying there in 1930, the greater part of his productive period was spent abroad.

This would matter less were it not that his range was unusually wide, while his output (since he was a perfectionist) was not particularly large. Moreover much of his best work was in portraiture — and portraits, since they are often commissioned, are usually slow to get to galleries. Meanwhile nearly all of the military art went straight to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. (It was good to see the big paintings here, reintegrated with the rest of the oeuvre.) Then there are the drawings, of impeccable draftsmanship, but in themselves serving to augment rather than make a reputation. And, finally, there are the sculptures — massive, monumental and effective — often showing a tendency to over-elaboration, with ideas that would work much better on canvas. (Lambert's eldest son Maurice, who became a famous British sculptor, reactively went for simplicity of line.)

by George W Lambert

oil on canvas, 184.0 x 184.0 cm

The real difficulty with Lambert — indeed the objection — arises from the display of paintings from the 1905–16 period. Lambert had scarcely set foot in England when, bowled over by seeing the Old Masters for the first time, he determined on becoming an academic painter. The Spanish seventeenth-century painter Velazquez was the major influence, evident in the group paintings of these years: in colours, tonality, and sometimes in direct allusion. Not that Lambert's paintings are derivative: he had too much originality for that. But the grand manner has been absorbed so totally that it sweeps up his wife, family, and Thea Proctor — who generally seems to have been in tandem. These were his models, and they become transfigured into representatives of the English upper crust. (Lambert did the same for a London lawyer, who becomes a regular country squire: gun in hand, his lady's stance affirming her haughtiness, while hunting dogs gambol nearby.) Even the Lambert family group going to the seaside, scarcely an exercise in the grand gesture, becomes a pretext for displaying the grand manner. There again are the disdainful, pouting faces, a projection of superiority or at least entitlement. Lambert's itch to impress combined with a flawless technique ultimately makes the room of canvases oppressive. This is imperial art.

____________________________________________________

The experience of expatriatism, however necessary, was somewhat unnerving for Australian artists, particularly those who left Australia with established reputations. Charles Conder dissipated his talent in frivolities. Streeton could not connect insightfully with the English landscape; his painting of The Centre of the Empire, Trafalgar Square, shows it to be a dead heart, with the little activity rendered blandly. With Roberts, too, expatriatism and removal from his inspirational roots must take as much blame for his decline as exhaustion from working on 'the Big Picture'. But unlike the foregoing, Lambert stood only at the threshold of making a reputation when he won the first New South Wales Society of Artists travelling scholarship; although 27, he had come to receive tuition relatively late, and so was much more open to new influences. Especially when they were old. But European art galleries enabled not just sudden exposure to a vital, missing ingredient; here was a young man, fatherless and of no particular country, eager to attach himself to a tradition which would at once provide connection and authorise him to cultivate a high, solitary style.

Lambert's first ambition, arising from the time he spent on his great-uncle's property in New South Wales, was to paint the Australian landscape. The very earliest efforts, included here, were in the style of the illustrator AH Fullwood. More interesting is On the Black Soil Plains: essentially a study of clouds, there is nonetheless an elegance in the disposition of a distant flock, and of a moving wagon; the painting is an indication of how Lambert might have developed had he stayed. More serious altogether is the vast Across the Black Soil Plains, with its team of horses pulling a high cartload of wool: a sense of movement is enhanced by the pattern of light and rhythms of energy, the whole given shape by the wagon rounding a bend. With blacks and browns of varying warmth, relieved by whites, there is already a hint of the group portraits to come.

It was Palestine that became the site of Lambert's greatest landscapes — not least because its harshness amplified the sun-struck tonalities he had known in Australia. As Andrew Motion puts it, Palestine 'shook George into originality'. His 'first loyalties were to what actually confronted him', rather than to 'artistic traditions he had worked so hard to assimilate'. More than that, as a war artist Lambert was determined to get every detail right, not only visiting the sites but even having a charge of Light Horsemen being re-enacted for his benefit. Aware of the impassivity of hilly landscapes to the human drama taking place below, Lambert at Gallipoli made the craggy heights themselves a protagonist, with the Anzacs melding into the steep slopes. Conversely, once back in Australia, he was capable of expressing his old affection for the countryside, as in Michelago Landscape, but what is more striking is the way the figures in his paintings have become almost evanescent. The Squatter's Daughter leads her horse into a formalised Streetonesque landscape; but she is a transitory presence. Later, Lambert would paint a country race meeting, at Tirranna; although not quite completed, it is plain that that there would remain something fluttery about the crowd, while the angularity of the figures show an affinity with the war paintings.

by George W Lambert

oil on canvas, 128.2 x 102.8 cm

by George W Lambert

oil on canvas, 77.0 x 62.0 cm

by George W Lambert

oil with pencil on canvas, strainer 134.7 x 170.3 cm, frame 152.8 x 189.4 x 11.6 cm

by George W Lambert

oil on canvas, 71.70 x 91.80 cm

A triangular form is also evident in Weighing the Fleece, a work commissioned by the owners of Wanganella near Deniliquin. Lambert painted it in eight days; it was 'a picture I've had in mind for 25 years'. The time span suggests it was something of a riposte to Tom Roberts' Shearing the Rams. Certainly it could not be more different in spirit: instead of the celebration of strong masculine labour, this painting endorses wealth and the social order. It is almost a frieze inside a pediment: at the top stand the scales, the fleece having just been placed on them. The calibrating needle is followed by the eyes of all those present, save for the two men handling sheep. On one side of the scales stand the woolbuyer and his assistants, while on the other the dominant figures are the station owner and his wife. He has his hand half in pocket as he assumes a haughty mien — casual proprietorship — while his wife is placed, seated, on an adjacent bag of wool. Some suggest that, while seeming a beneficiary, she is in fact no less a possession of the owner than the fleece. They are not wrong. This is a deeply conservative painting, where Lambert's toryism meets the Riverina.

Lambert's political views are scarcely mentioned in the catalogue, and may have been only loosely formed. They were marginal to his life and work. In his Lotty and the Lady, Lotty the maid is rendered sympathetically, but on another plane the lady sits eyeing her commandingly, her gloved hand firmly clasping a brolly; it intrudes on the careworn Lotty's space like a sceptre or a sjambok. Both women are presented with integrity; a representation of class relations was probably far from Lambert's mind.

by George W Lambert

oil on canvas, 106.0 x 78.0 cm

photograph by Jenni Carter, Art Gallery of New South Wales

More curious is the way that so many Lambert portraits present people showing distaste or disdain. Indeed the owner of Wanganella was so displeased with the depiction of himself and his wife in Weighing the Fleece that he refused to purchase it. Strikingly, a drawing for the flowergirl in Important People has a tenderness which the more public painting loses. But then some of Lambert's subjects seem deliberately presented as being unpleasant. Whatever the acquiescent catalogue might say, the woman in the Smile of Pan sports not a smile so much as a sneer. Similarly, the woman in the superbly painted The White Glove, for all her finery, bears a repulsive expression. The central position of the glove, in the painting as in the title, may discount her own position; but if so, it is a surrender willingly (if thoughtlessly) made.

____________________________________________________

Anne Gray's catalogue is sumptuous, scholarly and informative. But it is a pity that Lambert's works as a war artist, on show elsewhere, receive little coverage; this detracts from the catalogue's value as a monograph. Still, it is good to have reproductions of paintings whose present whereabouts are unknown.

The catalogue points out that Lambert, in Sydney in the 1920s, encouraged the young and was, to a modest degree, influenced by modernism. Like Barry Humphries in reverse, Lambert's concern with style made him Tory in England but prepared to flirt with radicalism in Australia. Nonetheless it is the group paintings of the Edwardian period, so superb in technique, which seem the keystone of his impressively diverse achievement. The National Gallery of Australia clearly thought so: throughout the exhibition it was offering, amidst potted palms at adjacent tables, high tea.

Jim Davidson is an honorary fellow of the Australian Centre at the University of Melbourne.

|

Institution: |

National Gallery of Australia |

|

Curatorial team: |

Anne Gray, Head of Australian Art |

|

Design: |

Adam Worrall, Assistant Director, Exhibitions and Collections |

|

Venue/dates: |

National Gallery of Australia, 29 June 2007 – 16 September 2007 |

|

Publication: |

George W Lambert Retrospective: Heroes & Icons, by Anne Gray, National Gallery of Australia, 2007. RRP $39.95 |