Fig. 1. Radiola television, AWA Australia, 1956.

Powerhouse Museum collection

Since opening in 1988 with a permanent exhibition on the history of film in the 1930s, Sydney's Powerhouse Museum has energetically staked out popular culture as its territory. In addition to displaying exhibitions from other organisations focused on internationally successful films (Star Trek, Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings), the Powerhouse developed Real Wild Child! Australian Rock Music Then and Now (1994–1996), Circus! 150 Years in Australia (1996), Cars and Culture: Our Driving Passions (1998–1999), and Spinning Around: 50 Years of Festival Records (2001–2002). With this track record it is not surprising that the Powerhouse Museum should turn its attention to television as a cultural form worthy of commemoration and analysis.

The Powerhouse has its own history with television: in 1947, nearly a decade before the beginnings of television in Australia, a non-working television receiver and a miniature model of a TV studio were exhibited in the old Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences building, forerunner of the Powerhouse. Displaying these objects at that time not only heralded the advent of television but reaffirmed the museum's commitment to collecting and interpreting scientific and technological innovations. The only other Australian collecting institutions to have developed exhibitions on television — the Museum of Contemporary Art (Sydney) in 1991 and, currently, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (Melbourne) — approached television from a visual or screen culture perspective.

The Powerhouse Museum's current exhibition On the Box draws on the Museum's strengths in decorative arts and design, social history, and science and technology. These collections inform the exhibition's intellectual approach and endow it with a breadth and depth that would be hard for another institution to replicate.

According to curator Peter Cox, the exhibition has three broad goals: to tell the story of television from a critical perspective which would attract and engage visitors; to strengthen the Powerhouse's position as a serious player in the study and interpretation of popular culture, screen-based visual media and communications technology; and to shore up the credibility of television as a significant part of our cultural heritage. On another level, On the Box aims to communicate that television functions as an 'imaginary public archive' which contributes to our sense of national identity and our understanding of who we are as a community.

Academic interest in social history, media studies, popular culture and cultural studies has dramatically increased in the last 20 years, with the significance of the web, television and radio the focus of substantial research and debate. In light of this interest and activity, there must be little doubt now that television is a legitimate part of our cultural history. It wasn't always this way, and one of the strengths of the exhibition is that it reveals the extent to which television has dominated our domestic lives and our leisure time, shaped our understandings of the current and past world, and reflected and expressed social change. These themes and others — television and national identity, television and memory, and television and sexuality — were explored at a three-day conference in December 2005, organised by the Transforming Cultures Research Centre at the University of Technology, Sydney, and held at the Powerhouse Museum.

On the Box gives us the opportunity to reflect on a number of museological and historical issues, such as the risks of collecting or exhibiting around contemporary themes. The museum profession is generally doubtful about the merits of collecting or interpreting contemporary material culture: not enough time has passed for the significance, or lack of significance, to be well understood and, with some exceptions, mass-produced, disposable and everyday objects struggle alongside more unique historical objects to have resonance or impact in an exhibition context. There is an element of this problem in On the Box with, I suspect for some, too much merchandise. But for an old style ex–(social) history curator such as your reviewer, the curatorial point being made with this material is carried successfully: television content is imminently repurposable, and therefore has meaning well beyond what happens on the screen.

With the Australian Government currently lamenting the parlous state of history in schools, On the Box made me reflect on the contribution television has made to the popular presentation of Australian history. It is easy to forget that as a result of the success of the American miniseries Roots in 1977 and the advent of tax concessions for local film production, there was a boom of locally produced history-based tele-movies and mini-series in the 1980s. Convicts, the goldrushes, the ANZACs, the Second World War and the outback were a regular part of television programming, and for some audiences perhaps their only exposure to key aspects of Australia's past. Nearly always nationalistic and nostalgic, these shows did however have merit: authenticity was greatly helped by stories being sourced from award-winning or outstanding fiction and the use of historical advisers who were affordable through the healthy budgets available at that time.

With connecting to audience a strong part of the curatorial approach, On the Box gives visitors a number of opportunities. It can be experienced as a reassuring walk down memory lane with nostalgia operating at high levels; or it can be read as an unsettling signal about how communications technology has been transformed since 1956, and how digitisation, the internet and new relationships with audiences are currently seismically altering television's future. On the Box can also be a learning experience — a chance to expand knowledge and gain insights about something that is so familiar and taken for granted. From the exhibition we learn that genres have changed very little since the early days (with reality TV perhaps the only new form to emerge in recent years); that in fact when taken as a totality (and despite our own capacity for collective self-criticism) the quality and diversity of our television rates highly against that of other countries; and that we have had highly successful periods of exporting television programming.

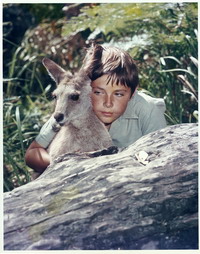

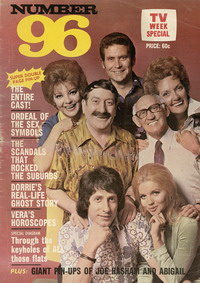

Undoubtedly, the exhibition will have the most meaning for those with 1950s and 1960s childhoods when television was modern, captivating and dominant in the lives of most Australian families. The visitors with whom I shared the exhibition one recent Saturday afternoon immersed themselves in the unadulterated pleasure of deep nostalgia, and everywhere cross-generational groups debated the comparative virtues of programs, transfixed for hours by the enticing historical footage. There were, however, a number of visitors who obviously found the content mysterious, perhaps too culturally specific and without much relevance to their lives: Mike Moore's wig from Frontline, Diver Dan's dancing shoes from Sea Change or Aldo's moustache from Number 96 does it for some of us, but clearly not everyone.

Louise Douglas worked at the Powerhouse Museum from 1984 to 1994 and since then at the National Museum of Australia. She is in the early stages of a PhD on Australian representation at international exhibitions and world fairs from 1901 to 1939.

Thanks to Peter Cox for his responses to questions about the exhibition.