In 1984 a solitary group of Pintupi people eventually made their way to an Aboriginal community to be reunited with relatives they hadn't seen for decades. The travellers had never worn clothes or seen a motor vehicle and they thought the aeroplanes they had observed flying overhead were mamu (ghosts). This event marked the final chapter in a saga which for the rest of the Pintupi and their neighbours had begun some fifty years earlier, when European settlement first began to encroach on their lives.

Colliding Worlds documents the remarkable history of the Western Desert people's movement away from being a hunting and gathering society — a process so many Aboriginal groups have gone through at one stage or another. What is so remarkable about the Western Desert experience is that it was so recent.

Courtesy Mrs DM Thomson and Museum Victoria

Colliding Worlds is the result of a collaboration between the Museum of Victoria and Tandanya, the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute in Adelaide, South Australia. It was first exhibited at Tandanya as part of the 2006 Adelaide Festival, and its original format has been largely maintained for the Melbourne Museum exhibition, which has been staged in temporary space in the Australia Gallery. This positioning away from the main Indigenous gallery (Bunjilaka) may have a significance of its own, a colonisation of sorts of the wider gallery space by an exhibition with a primary focus on Indigenous culture.

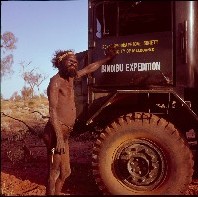

Entering the exhibition space we are immediately immersed in Western Desert life as it was before contact, through a series of large format colour photographs by the anthropologist Donald Thomson. These were taken during his 1957 expeditions to Bindibu (Pintupi) country and introduce the exhibition and set its tone. The images are hung midway on a black wall space forming a continuous line that directs the gaze of the viewer and orientates movement toward the next stage of the exhibition.

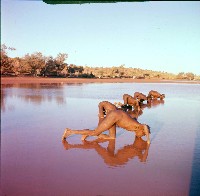

Set against the stunning backdrop of the red desert landscape, the photographs show Western Desert life as it has never been shown before, and can never be shown again. The raw power of these colour photographs lies in their immediacy — they look as if they could have been taken yesterday. The photographs reveal Thomson's fascination with the everyday. We see people going about their daily lives: drinking at waterholes, sitting beside windbreaks, digging for lizards.

Donald Thomson's interest in ordinary subjects has long been recognised, and a collection of his photographs titled Children of the Wilderness, posthumously published in 1983, is dedicated to this theme. Several of the photographs from this volume appear in Colliding Worlds. Some visitors will recognise the photograph from the cover of Thomson's 1975 book Bindibu Country. This strikingly beautiful and poetic image, showing five men drinking from a surface water near Labbi Labbi on the Northern Territory/Western Australian border, is surely among the finest ethnographic photographs ever taken.

Courtesy Mrs DM Thomson and Museum Victoria

In the centre of the room containing the Thomson photographs is a large light box positioned on the floor so that the viewer looks down onto it. Two images are shown side by side: an aerial photograph and a typical Western Desert style acrylic painting. The label tells us they represent impressions of the same landscape from different cultural vantage points. One is from the perspective of twentieth-century satellite technology, the other from the Dreaming.

The remainder of the exhibition is arranged chronologically, beginning with first encounters with missionaries and scientific parties in the 1930s. Colonial settlement began in central Australia from the 1870s and Hermannsburg mission was established soon after on Arrernte land, but there was little contact between the mission and groups occupying the desert further out. An extended drought in the late 1920s drove increasing numbers of Western Desert people east to seek refuge at the missions and ration depots.

The first missionaries tried to suppress traditional culture, but those who came later were more concerned at stopping the influx of hunter-gatherers. They established ration depots and food drops near waterholes to encourage people to stay in the bush. In 1932 a number of Western Desert people, and some southern Warlpiri, were met by members of the Adelaide University Scientific Expedition at Mt Liebig, central Australia. Many of these people came from traditional country much further west but were following others who had begun gravitating toward mission outposts.

The Mt Liebig expedition attracted some notable personalities, including EW Holden of General Motors-Holden's fame and Norman Tindale, one of the foremost anthropologists of the time. Their object was to 'study Aborigines untouched by whiteman'. Part of this involved taking life-sized plaster casts of Aboriginal subjects. Two plaster casts, of a Pintupi woman (Waripanda) and a Ngalia man (Mallitjukurupa), feature in the exhibition. Likewise, portraits of Aboriginal people were taken and placed on 'photo identification cards'.

The exploitation of Aboriginal people for scientific purposes will be disturbing to many. Colliding Worlds makes no attempt to hide such dark and gloomy subjects. The plaster casts and photo identification cards serve as reminder of a time when Aboriginal people were treated as curiosities, as fading relics to be studied and recorded for posterity. At the same time, the material collected by the Mt Liebig expedition is historically significant and richly detailed. So although the photo identification cards look like mug shots, they also link images to known individuals and to other information, such as kin classifications. Biographical detail of this type is rare in early ethnographic collections.

If we are allowed to forget, for a moment, the manner and purpose of their production, the plaster casts have a kind of dignity to them. Certainly this is enhanced here by their display alongside other artefacts, including body ornaments, tools and utensils. These are personal effects, collected from the same individuals. Such attention to detail is provenance at its best, and owes much to the foresight of the collectors.

Two of the men whose photographs appear in the display, Mick Namarari and Johnny Warangula, were both formative in the Papunya Tula art movement. The photographs alert us to their presence at Mt Liebig in 1932, providing valuable insights into their early life histories. As part of the extensive documentation carried out by Norman Tindale and his collaborators, Aboriginal men were provided with paper and crayons, producing a series of drawings of traditional designs. Four are displayed here, including one by Johnny Warangula's father. As a child at Mt Liebig, he may have seen his father drawing this image, possibly the first time he would have seen art produced in a non-traditional medium.

From 1932 we move to the 1950s. Images depicting rocket launches from the firing range at Woomera herald the coming of the space age and the globalisation of technology into which Pintupi and other desert foragers were involuntarily drawn. This was to have ramifications for the Western Desert people who were at this time still living an independent foraging life in the bush.

The period from 1955 to 1964 was the one in which many — perhaps most — Pintupi and Ngaatjatjarra people were contacted for the first time. Donald Thomson's expeditions affected only small numbers of people, none of whom returned with him. Patrols carried out by Jeremy Long of the Northern Territory Welfare Branch were to have a more lasting effect. Many of those Pintupi contacted by Long accompanied him to settlements at Haasts Bluff and Papunya. Photographs and stills from an ABC documentary film shot in 1964 show the 'coming in' of some of the later westernmost groups. We can see in these photographs the influence of European goods, such as a woman carrying a metal billy-can in a wooden dish, some cloth draped around her waist. Objects collected by Thomson are also displayed here, including a spear-thrower with an incised totemic design, some twine sandals and a wooden dish.

Newspaper clippings of Thomson's 1957 expedition, reproduced from the Melbourne Age, lead into a short account of the arrival of the group in 1984. 'We find the lost tribe' announces the front page of the Melbourne Herald on 24 October, revealing something of the media hoopla surrounding that later event. Then we see the desert people as they are in 2004, two decades on, looking like any other contemporary Western Desert people and somewhat bemused by all the fascination and hype.

The final text panels deal with contemporary issues and accounts of contact given by Aboriginal people themselves. Many of these accounts focus on the 'strangeness' of their first encounters. Western Desert people struggled to accommodate new experiences within their existing framework of meaning. A series of acrylic paintings provides a stunning finale and remind us that Indigenous perspectives of these events were informed primarily by the perspective of the Dreaming. Two large paintings shown here by Uta Uta Tjangala, and another by Willy Tjungarrayi, both adult men before they encountered Europeans, are typical of the mid-eighties Papunya Tula style. Linda Sydick's painting provides a figurative interpretation of the time her family first encountered a windmill, which is shown with snakes emanating from the blades, investing the object with the power of a mythological being in an attempt to make it more comprehensible.

Colliding Worlds is presented as a straightforward narrative. The period 'before Europeans', captured by Thomson's photographs, is followed by the historical past represented as a linear progression from the earliest to the most recent. Objects tend to be displayed in the middle of the room with text panelling around the walls. There was evidently a decision taken to exclude any audiovisual content, which is understandable, given the large number of text panels — quiet spaces are needed to read and absorb the information.

As always, the real strength of an exhibition lies in its story. Here is where Colliding Worlds excels: by allowing us to trace, through the example of the Western Desert region, an amazing story of twentieth-century contact and how it unfolded through time. There is no other region in Australia which has such a richly documented and recent history of interaction. Along the way, Colliding Worlds challenges some of the assumptions we hold about contact and helps us to better understand Australia's coming together as one community.

Peter Thorley, a curator at the National Museum of Australia, has a long history of working with Western Desert people and holds a PhD in desert archaeology.