Museum arabesque: A French universal museum in the Arab world

Museums have long been among the West's most successful cultural exports. The best evidence of this is the enthusiasm of non-Western societies to import them. This enthusiasm is not new. In the 19th century museums served as symbols of culture and refinement, enhancing the status and authority of their makers. Now, along with skyscrapers and neon lights, they are symbols of modernity: every up-and-coming nation and city must have one: architecturally exuberant, preferably designed by an architect of international stature, and possibly linked with one of the great museums in the West.

Qatar and the United Arab Emirates are among the most recent to join the trend. Abu Dhabi in the UAE is aspiring to become a cultural centre, with a cluster of museums planned or under construction on Saadiyat Island, a 27-square-kilometre site 10 minutes from the city centre. These include what will be the largest museum in the Guggenheim franchise, designed by Canadian/American Frank Gehry and now planned to open in 2017; the Zayad National Museum, focused on Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan and the nation he created, designed by British architect Norman Foster and drawing on expertise from the British Museum; and the Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by French architect Jean Nouvel and based on close collaboration between the UAE and Musée du Louvre, together with other Parisian museums, the Bibliothèque nationale and the Château de Versailles. The Zayad National Museum is due to open in 2016 and the Louvre Abu Dhabi in December 2015.[1]

The naming of Louvre Abu Dhabi signals clearly the value attached to association with the world's most visited museum. The privilege of association did not come cheaply. In return for branding rights, loans and museum expertise over a period of 30 years, Abu Dhabi is paying the French government US$1.3 billion. The naming affirms the new museum's ambitions and purpose. It is to be 'a universal museum', representing all regions and periods, and displaying 'major objects from the fields of archaeology, fine arts and decorative arts'. According to the official website,

the universal approach suits Abu Dhabi well, reflecting the city's position at the crossroads of east and west, and its vital ancient role in the days of the Silk Route, when the region linked Europe and the Indian Ocean, opening up exchanges between Asia and Africa. The museum will reflect the region's role as a crossroads for civilisations.

… The aim is to avoid the isolation of cultures and disciplines in order to offer a comprehensive history of art, providing an alternative to the particular vision of the world that has long been proposed by museums.[2]

The architecture is spectacular, with a grand flat white dome and water features inspired by Arab architecture, presenting a cool haven between desert and sea. The building will provide more than 6600 square metres for permanent galleries and more than 2300 square metres for temporary exhibitions. While early displays will draw significantly on loans from French institutions, the museum entered the art market several years ago and is on the way to developing a substantial collection of its own.

chlorite body and headdress, calcite face, 25.3 cm

photograph by Thierry Ollivier, © Louvre Abu Dhabi, LAD.2011.024

Unsurprisingly, Louvre Abu Dhabi has provoked much controversy, especially in France, where an online petition declared 'Museums are not for sale'.[3] While many anxieties relate specifically to French cultural sensitivities, the new museum raises issues of broader interest relating to the economic value of museums and collections, museums as instruments of cultural diplomacy, the role of architects, museums and globalisation, and much more. In particular, it offers an opportunity to reflect on the concept of 'the universal museum'. The Louvre (Paris!) website anticipates the challenge:

The first, and most obvious, perspective of Louvre Abu Dhabi's universalism stems from the history of museums and particularly that of the Louvre, whose excellence will be conveyed by the future institution. The palace that became the Museum National in 1793 was a product of the encyclopedic thought of the Enlightenment and of the French Revolution.[4]

Such claims have prompted art historian Andrew McClellan to respond, in an article published in 2012, that the new Louvre 'appears set to re-inscribe the familiar western story of art', and that the Louvre in Paris was 'essentially reproducing itself in the Persian Gulf while claiming to do something new and different'.[5] In other words, does globalisation amount to yet another instance of cultural imperialism? Or, is universalism really French, or Western European, universalism?

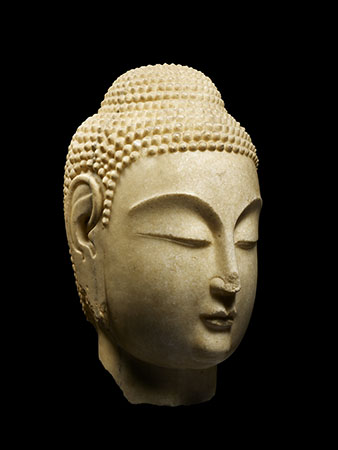

white marble, 50 cm,

photograph by Thierry Ollivier, © Louvre Abu Dhabi

One way of discovering the meaning of the new museum's claims to universality is through its collections. A selection of more than 160 objects has lately been showcased, first in Abu Dhabi, then in Paris, in an exhibition titled Louvre Abu Dhabi: Birth of a Museum, which I had the good fortune to see at the Louvre last May. The range of objects, in date, place and format, is remarkable, extending from an eighth or seventh century BCE gold bracelet from Iranian Azerbaijan to a recent painting by an American abstract expressionist, with a Greek sphinx, a Chinese Buddha, a Benin bronze rooster, Persian miniatures, Roman marbles and pages from the Qur'an along the way. There is a Bellini, a Gauguin, a Manet, a Picasso, and much more.[6]

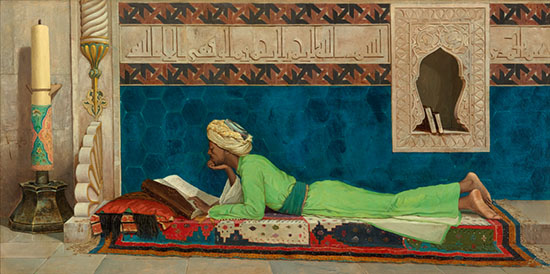

by Osman Hamdi Bey (Istanbul, 1842–Galatasaray Islet, 1910)

oil on canvas, 45.5 cm x 90 cm

photograph by Thierry Ollivier, © Louvre Abu Dhabi, LAD.2012.017

The captions were consistently accessible, informative and engaging, and the theme of 'shared commonalities' well sustained. My favourites included an 1878 oil painting of A Young Emir Studying by Osman Hamdi Bey, born in Constantinople and trained in Paris, who captured Eastern subjects with the help of Western techniques and traditions; studio portraits by English photographer Roger Fenton, which impeccably express Orientalist imaginings; and an exquisitely decorated octagonal box from Tang Dynasty China. The box is accompanied by a digital interactive (a model of its kind) which shows how its ornamental motifs were 'inspired by the Iranian art of the Sassanids, with whom the Chinese emperors were in close contact at the time'. How each of these might rank in terms of a universal art aesthetic I have no idea, but they certainly draw out the theme of cultural exchange.

bronze, 81 cm

image published in L Sickman (ed.), Masterpieces of Asian Art in American Collections, New York, 1960, no. 23b

© Louvre Abu Dhabi

There are no Australian objects in Birth of the Museum – we will have to wait until the opening of Louvre Abu Dhabi to see how the continent is portrayed in 'the first universal museum of the twentieth century'. The preview exhibition does, however, include one object that once called Australia home. This is a sculpture of dancing Shiva from Tamil Nadu, which for several years graced the one of the Asian galleries in the National Gallery of Australia. It was sold in 2009, after the Gallery acquired a more magnificent Shiva, dancing in a ring of flames, from now infamous New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor. After the new Shiva was proved to have been looted, the gallery was obliged to return it to India (a feat performed with sufficient spin to give the impression Australia had achieved a diplomatic coup).[7]

The opening of Louvre Abu Dhabi will offer Australians, especially museum professionals, the opportunity to reflect on what they have lost.

Endnotes

1 On the precinct, see www.saadiyat.ae/en/ [accessed 23 Oct 2014].

2 http://louvreabudhabi.ae/ [accessed 23 Oct 2014].

3 Media references include 'Gulf Louvre deal riles French art world', BBC News, 6 March 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6421205.stm [accessed 23 Oct 2014]. See also Jean Clair, Malaise dans les musées, Paris, Flammarion, 2007; and Mary Bouquet, Museums: A Visual Anthropology, Berg, London, 2012.

4 http://www.louvre.fr/en/louvre-abu-dhabi [accessed 23 Oct 2014].

5 Andrew McClellan, 'Museum expansion in the twenty-first century: Abu Dhabi', Journal of Curatorial Studies, vol. 1, no. 3, 2012, 271–93. McClellan offers a valuable critique of the Abu Dhabi developments.

6 All of these are illustrated in Louvre Abu Dhabi: Birth of a Museum: Album of the Exhibition, Paris, Flammarion, 2014; and most appear on the Louvre Abu Dhabi website, http://louvreabudhabi.ae/.

7 The Shiva story was extensively reported in the Australian media. See, for example, Joyce Morgan, 'Is the NGA's 'looted' Shiva a statue of naivety?', Saturday Paper, 15 March 2014, www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/law-crime/2014/03/15/the-ngas-looted-shiva-statue-naivety/1394802000#.VEnfaWAcQdU [accessed 23 Oct 2014]; Rachel Kleinman & Amrit Dhillon, 'The National Gallery of Australia dances into trouble with Shiva', Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 2014, www.smh.com.au/national/the-national-gallery-of-australia-dances-into-trouble-with-shiva-20140317-34xui.html [accessed 23 Oct 2014]; transcript of ABC TV Four Corners program, 'The dancing Shiva', 24 March 2014, http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/stories/2014/03/24/3968642.htm [accessed 23 Oct 2014]. NGA media releases are at http://nga.gov.au/ABOUTUS/press/Default.cfm [accessed 23 Oct 2014]. The fraud was exposed on http://chasingaphrodite.com/, which follows the story through to the repatriation of Shiva in September 2014 [accessed 23 Oct 2014].