Villa Alba Museum

Studley-park is acknowledged to be the finest situation for a residence in or around Melbourne, and from the elevated position, gravelly soil, and other natural advantages, it enjoys an exceptionally pure and salubrious atmosphere, entirely free from dust. No better proof of this can be had than that it has been selected as sites for such mansions as Waverley, Studley-house, Belmont, Clutha, Villa Alba &c.

Argus, 26 October 1876, p. 2.

Impressive in its seeming austerity, Villa Alba stands today as a house museum located in Studley Park, in Melbourne’s north-eastern suburb of Kew. It presents the union of the fine and ornamental arts in its painted interior wall decorations, created soon after the mansion was built in 1883. Villa Alba has attracted little scholarly attention, and no published work engages with the complexity and iconography behind the painted decorations, nor with the context within which these decorative works were created.[1] This case study posits Villa Alba as the only surviving example of the work of key Victorian artist-designers, the Paterson brothers, and casts fresh light on their company, identifying it as one of the premier art decorating firms in Australia from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries. Analysing the Patersons’ work reveals the imagination, skill and decorative styling of Scottish artists working from Melbourne during this period, and the fertile Scottish nexus between these artists, their friends, exhibiting societies and patrons. The evaluation of the house’s artistic and architectural significance is also used to consider the various ways in which Villa Alba can be interpreted in its current incarnation as a house museum without a collection.

Introducing Villa Alba

photograph by Russell Winnell

Villa Alba’s first incarnation was a modest home called ‘Studley Villa’. It was originally part of the Studley House estate belonging to wealthy pastoralist James McEvoy, who maintained pastoral stations and leases around New South Wales. McEvoy gave the house, on a parcel of land adjoining Walpole Street, to his only daughter, Anna Maria, upon her marriage to William Greenlaw at St Francis Church in Melbourne in August 1862. For much of his life William Greenlaw was as ambitious and determined as he was a lucky opportunist. A Scottish (probably tenant) farmer’s son, drawn to the prosperity of Melbourne from Edinburgh during the early years of the gold rush, he arrived in Melbourne in 1853, aged 22. Starting with the Colonial Bank of Australasia as a junior clerk when it was incorporated in 1856, he rose to the position of general manager in 1871.

The Greenlaws had renamed their home ‘Villa Alba’ by 1867,[2] but it was not until the early 1880s that the original house was demolished and the current house, described in the real estate rhetoric of the times as a ‘mansion’, was built. The change in name, and the building of the larger residence, reflect not only William Greenlaw’s increasing wealth, but also his desire to satisfy his beloved wife’s desire for beautiful surroundings in her middle age, not to mention the needs of their six growing children, born between 1863 and 1873.[3] The name also held historic associations for him: Alba is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland and the name change attests to Greenlaw’s pride in establishing wealth through enterprise in Australia, as a patriotic Scotsman.

The new, symmetrically fronted, double-storey Italianate villa with picturesque Norman and Romanesque revival detailing was built between 1882 and 1884. The villa was well situated, and still is, although the now profuse vegetation in the surrounding locale was probably sparser then, forested but worn down in areas by grazing cows. Nestled across from the tall trees and indigenous plantings of the Studley Park nature reserve, Villa Alba once overlooked the Yarra River and sided the land crest down to the then working-class areas of Abbotsford and Collingwood to the west. Originally on a land size of nearly two acres (8000 square metres), it stands towards the top of Walmer Street in Kew, and its southward-facing portico entrance and tower window provide views towards Toorak and the ridge of Melbourne’s inner southern suburbs. Miniature winding paths and cul-de-sacs edged with ferns once refreshed visitors as they wandered around the villa’s conservatory, graced by a water fountain, within the garden of the mansion.

Greenlaw claimed to be Villa Alba’s chief architect and no building plans or tenders by architects have come to light to prove the contrary. Architectural historian Miles Lewis has suggested that Greenlaw consulted the architectural firm of Smith & Johnson, who designed the new grand headquarters of the Colonial Bank of Australasia, which opened in March 1882.[4] A speculator, Greenlaw may have suppressed information concerning the architects, the building and the payment of the mansion, which he arranged through the Colonial Bank. Whatever the circumstances, he built a fine residence to replace the old Villa Alba, and commissioned interior art decoration that put his taste and patronage on a par with director of the Colonial Bank, Joseph Clarke, who owned Mandeville Hall, Toorak.[5] Indeed, Greenlaw’s crest was prominently positioned amidst the ceiling frescoes in the entry hall at Villa Alba, and was described by Table Talk as ‘a vulture with an oak branch in its mouth’.[6] Later identified as an eagle’s head, this family crest appears in the stair hall ceilings and above the front door it is etched into the glazing.[7]

‘CS Paterson Brothers ... Painters and Decorators in general’

Between 1883 and 1884, Scottish immigrant decorators, Charles, James and Hugh Paterson, artfully brought Villa Alba’s interior into the modern world of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, a moniker coined by the famed visiting journalist George Augustus Sala.[8] Established by the mid-1870s, Paterson Brothers rose to prominence through the reputation of the firm’s work at the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition and for the art decorations of the principal rooms of hardware and iron foundry magnate William Kerr Thompson’s mansion, Kamesburgh in North Brighton, directed by Charles Stewart Paterson the same year. No longer extant, these art decorations in some ways anticipated the work later carried out at Villa Alba. In the hallway dado at Kamesburgh, a medieval diaper pattern was alternated with panels of vases of flowers, representative of each season, naturalistically painted on a black ground, and the walls were ornamented with a stencilled horse-chestnut pattern to produce a silken effect, a variant of which decorates the walls of the entrance hall at Villa Alba. Similar to the figurative work along the hallway frieze at Villa Alba, a scattering of nude ‘putti’ at prankish play or monastic study lined the frieze at Kamesburgh.[9]

photograph by Russell Winnell

Within a year, Paterson Brothers had returned to Kamesburgh to decorate the smoking and billiard rooms; completed extensive decorating work for the residence of the Edinburgh-born merchant and politician, James Balfour; and carried out work at Beaulieu, the Toorak residence of Mars Buckley (of Buckley and Nunn renown). The Argus commented that the principal feature of Kamesburgh’s billiard room was the hand painted frieze depicting a group of wrestlers from ‘earlier times’, placed on a background of blue and gold, in ‘strict accordance with medieval art’. [10] This must have been the work of Hugh Paterson, who gained distinction in painting figures for the firm, especially after he returned from Scotland where he had worked as a figure decorator with a principal art decorator, Cornelius, in the late 1870s. The smoking room at Kamesburgh was treated in the Japanese style. Its green-grey tinted walls were covered with an irregular diaper of plants and bamboos, the frieze above illustrated birds flying amidst plants and flowers, and the painted ornament on the dado depicted clusters of decorated Japanese fans.[11]

Brilliant colourists with a keen sense of ornamental design and composition, the Patersons exemplify the artistic talent, business acumen, training and ambitions of Scottish immigrant decorators in Australia working in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[12] Their firm was not the only one of its kind in Australia, but Paterson Brothers was without question the leading art decorating firm in Melbourne. From the 1870s, the term ‘art decorator’ in Australia implied the work of a decorator who strove to achieve the harmonious union of beauty and functionality in interior ornamentation. Attracted by the colony’s prosperity, talented art decorators from around the world poured into Victoria during the 1870s and 1880s, forming a large and distinct group of cosmopolitan artists who enriched the interiors of many private and public buildings in the capital and regional towns.[13] Paterson Brothers competed with other prominent art decorators like SW Mouncey and Scottish-born Robert Reid for prestigious commissions. Further, the company sub-contracted much of the work at Villa Alba to other artists, most of whose identities are lost to history, apart from the small initials discovered hidden amidst the decorated ceilings and friezes at Villa Alba in recent decades.[14]

Inside Villa Alba

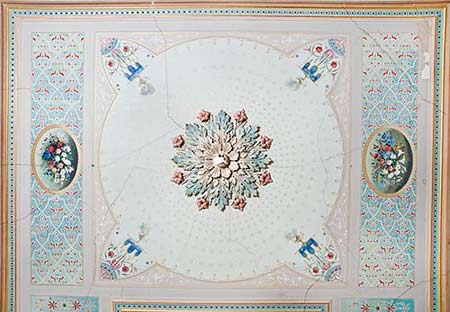

At the height of its reputation when Greenlaw commissioned the company, Paterson Brothers brought to Villa Alba a fashionable, cosmopolitan eclecticism that combined freely French rococo, medieval, neoclassic and the Italian renaissance periods, drew on the Geometric and Exotic styles and made strong use of stylised natural motifs. The delicate, ornamental spirit of art-for-art’s-sake aestheticism tempered this stylisation of nature. The composite repertoire of decorative styles at Villa Alba was modern, and the scrolls, cartouches, swags, medallions, trailing Grecian ivy motifs and meanders, the interlacing of patterns and abstract ornamental motifs articulate the overall compositions of the ceilings, skirts, panels, doors and friezes. Upstairs, the large master bedroom ceiling combines illusionism[15] with roundels of fairy maidens, cherubs, flower garlands, lacework and stars. The decoration of the dressing room and bathroom off this principal bedroom was in a similar style, with ‘the addition of a central subject painted in the Watteau style’.[16]

photograph by Russell Winnell

The fire surround of another bedroom is exquisitely hand painted with trailing flowers, the hearth and sides set with a medley of artistic tiles, and the main bathroom at the end of the upper hall is diapered with a striking Gothic geometric pattern, as was the kitchen off the vestibule downstairs.[17] Throughout the house, touches of gold outline the edges of the intricate patterns and enrich the colonnettes and capitals defining the lines of doorways and window bays. The fill areas of the drawing room walls were left free of ornamental patterns and painted a monochromatic tone to offset the array of Aesthetic hanging cabinets and carved, inlaid and ebonised brackets burdened with ornaments, and the pictures, mirrors and prints lining the walls.[18] Stained glass was not used, and the fine etched glass, patterned with vases of leaves and flowers, aside the entrance door, and the fanlights of Villa Alba, are visual relief to the harmonies and chromatic contrasts of the painted art decorations.

photograph by Andrew Montana

the upper frieze and cornice details

photograph by Russell Winnell

Walking along the upper hall at Villa Alba towards Anna Maria’s boudoir is like strolling through a painted garden. The deep dado, bordered by a geometric medieval-inspired pattern, comprises painted panels of pretty naturalistic flowers issuing from Aesthetic classical urns. Signor Ulysses Rizzi, an acclaimed flower painter subcontracted by Paterson Brothers, purportedly painted these.[19] The central wall section is also diapered but is yet to be uncovered by the conservators. The wall decoration of Anna Maria’s intimate, Moorish boudoir, now revealed, shows diapered soft pink and gold Islamic and fleur de lis motifs all on a blue-greenish ground, flanked by flat architectural open compartments in soft pink.

These surmount a prune-coloured dado decorated with a repetitive schema of framed ‘sacred’ ibis fowl and flower vases, and this ‘oriental’ room’s ceiling features flowers, fuming urns, Arabic motifs and Anna Maria’s monogram, all centred by a richly unfolding, gilded ceiling rose.

photograph by Russell Winnell

photograph by Russell Winnell

photograph by Russell Winnell

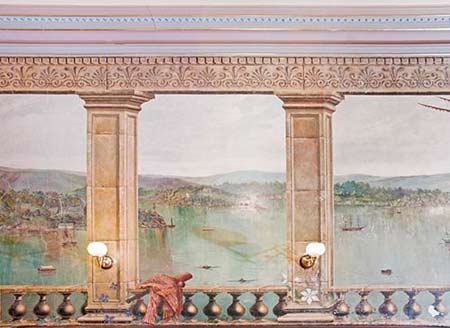

Fathomed by trompe l’oeil colonnades and bordered beneath by a deep, neo-Grecian upper-edged dark wainscot, these magnificent murals of the Sydney harbour and the Edinburgh hills proudly face each other. Probably adapted from a photograph of the harbour taken from the tower of the Garden Palace at the time of the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition, the mural depicts views of ships and a fleet at anchor surrounded by fledgling suburbs and hills on a cloudless summer’s day.

photograph by Russell Winnell

The view of Edinburgh shows a sweeping view of Arthur’s Seat, the Scott monument and the Castle ‘growing out of the rock’. Resplendent Scottish trophies and the royal coat of arms are painted above the entrance doorways from the connecting hall and towards the service quarters of the house. Exactly who painted these murals remains unclear. John Ford Paterson returned from Scotland in early 1884. He is likely to have had aesthetic input into the composition, especially as the murals were described by the press as rendered in a style worthy of the fashionable, naturalistic landscape painter of the colony, Louis Buvelot, whose heightened, light-suffused effects John Ford Paterson greatly admired.[21] The murals may very well be the creations of the well-known Scots-born scenic painter, watercolourist and decorative artist George Gordon, a great friend of Hugh Paterson.[22] As a decorative artist and scene and drop-curtain painter for the theatre, George Gordon was well regarded in Melbourne and Sydney for his atmospheric landscape settings, undulating horizons, depictions of nature, knolls and distant hills, in which rural buildings nestle among trees and below hazy cloud-drifted skies.[23] Certainly, contemporary descriptions of Gordon’s work for the theatre parallel the visual effect of these murals at Villa Alba.[24]

photograph by Russell Winnell

Other Scottish themes are to be found in the dining-room frieze, which depicts scenes from Sir Walter Scott’s popular Waverley novels, Rob Roy and The Heart of Midlothian, painted by Hugh Paterson. The Aesthetic grate tiles of the upstairs master bedroom were designed by the Scottish-born artist John Moyr Smith for Minton. These were also based on Scott’s novels, and launched at the 1878 Paris International Exhibition. Rich and warm, the colour and tonal contrasts of the painted interiors are like musical relationships between the proportionate parts, exemplifying what the eminent Scottish art decorator and mathematician David Ramsay Hay espoused in his science of the beautiful and colour harmonies from the 1830s. Indeed, Hay influenced the work of the eminent Scottish decorators Purdie, Bonnar and Carfrae, with whom James Paterson was apprenticed before he came to Melbourne in 1873.[25]

The house furnished

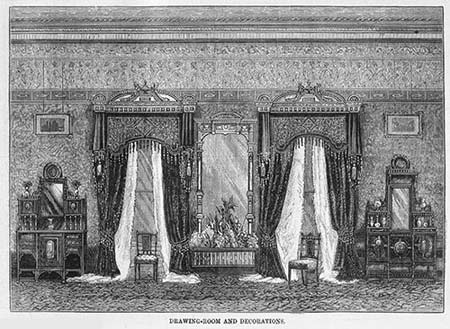

‘Nature, I loved; and next to nature, Art’, wrote the English philosopher Walter Landor in his poem Finis (1849). This line characterises the theme of leaves and flowers that once linked the furnishings at Villa Alba — the plush velvet upholstery fabrics, the silk hangings, the carved patterns on the cabinetry and seat furniture — to the painted art decoration that formed their backdrop.

The cabinet at the left was later purchased for the drawing room of Villa Alba by Mrs Greenlaw, and is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria.

State Library of Victoria

Inside, the villa was furnished predominantly by Melbourne’s leading firm of cabinetmakers, decorators, retailers, and importers, WH Rocke & Co., of Collins Street. Anna Maria Greenlaw, who seems to have commissioned much of the furniture, may well have seen and been impressed by Rocke & Co.’s large, fashionable display of outfitted apartments at the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition, Melbourne’s first international exhibition. Talented Scots immigrant decorator and artist John Mather designed the Aesthetic interior decorative scheme of the Exhibition Building, and the Greenlaws also bought for Villa Alba furniture hand painted by Mather. A three-fold black silk satin screen, exquisitely hand painted by John Ford Paterson with flowers and birds, and shaded by hanging Madras window curtains, once graced the boudoir.

The whereabouts of the once large collection of furniture, textiles and decorative arts that filled Villa Alba, dispersed through auction in 1897, is largely unknown today. A coved satinwood overmantel depicting scenes from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, made by WH Rocke and Co. and painted by Paterson Brothers, was identified decades ago in an antique shop by Terence Lane, curator of decorative arts at the National Gallery of Victoria. Purchased, this overmantel was returned to the house.

photograph by Russell Winnell

One other surviving piece of furniture from Villa Alba is the drawing-room cabinet made by Rocke & Co. and hand painted by Mather. This is now in the National Gallery of Victoria’s collection. We know from newspaper reports that Anna Maria Greenlaw commissioned a colossal satinwood cabinet bearing the date 1884 on its carved pediment. It featured recesses, spindle galleries, and compartments, and a large reclining canopy hand painted with landscapes, sprites and flowers – and it was only one part of a set.[26] En suite, the dazzle of mirrored cabinets, over-doors, tables, chairs, screens and wall cabinets formed a 16-piece ensemble, all from Rocke and Co. The same company also made the huge mahogany dining suite, comprising chairs, dining table, sideboard, dinner wagon, carved overmantel and coal cabinet, and the massive furniture for the principal bedroom.[27]

A rare glimpse of Villa Alba’s peopled interiors is given in an account of the wedding of the Greenlaws’ third daughter, Edith Maude, born in 1867, to M Hoffmann, also of Studley Park, at Holy Trinity Church, Kew, in 1889. Standing in the atmospheric, 1860s bluestone Anglican church, decorated with ribbons, blooms, garlands, flower baskets suspended above the altar and floral wreaths encircling the ends of the pews, Edith was married with bunches of white heather adorning her gown ‘in compliment to her father’s [Scottish] nationality’. After the ceremony, Anna Maria Greenlaw held a reception at Studley Park where:

the drawing-room of her residence ‘Villa Alba,’ was most fairy like in its adornments of flowers and choice plants arranged in artistic bowls; while at the upper end a beautiful bank of blossoms rose against a panel mirror, which reflected through a flowery vista the animated scene, with its moving forms and bright colours. The dejeuner was laid in the dining-room; and under the skilful management of the caterers, Messrs. Edlinger and Goetz, the affair passed off with éclat. The bridal cake was unique, being surrounded with a figure in Parian marble, holding a vaseful of choice white blossoms. A large marriage bell of white flowers hung over the bride’s head as she sat at the table. The newly-wedded couple left during the afternoon for Sydney, where the honeymoon was to be spent.[28]

Beyond Villa Alba

The decorative work at Villa Alba must have helped finance Paterson Brothers’ new showrooms, which opened in 1884, the same year John Ford Paterson returned from Scotland with the latest pattern books and art journals to inspire his siblings’ talents. The Patersons’ fashionable taste is evident from the press descriptions of the firm’s new premises at 33 Collins Street-east, an upwardly mobile move after its previous warehouse premises in little-Collins Street. This new upstairs salon was decorated with a frieze of flying Japanese birds and plaques painted on a rich gold ground. As with the wall fills of the drawing room at Villa Alba, so the walls of the new Paterson Brothers premises were left bare of ornamentation to offset the bronzes, marble statuettes, trophies and antique furniture in the salon, and to accommodate the visual poetry of John Ford Paterson’s large oil paintings of Scottish and colonial scenery.[29] The Melbourne journal Once a Month singled out one of Paterson’s paintings on view at the showroom, destined for exhibition at the 1886 Indian and Colonial Exhibition in South Kensington, London. ‘There is great breadth and freedom’, the columnist enthused, ‘the colouring is extremely pure, and the sea and cloud effects even superior to what is generally seen from the same brush’.[30] Shortly afterwards, John Ford Paterson opened a studio in the same premises decorated by his brothers, and furnished by the fashionable Melbourne importers, the Italian Trading Company, followed in 1889 by one in the inner suburb of Carlton, its walls painted in deep Etruscan red and one of them lined with antique Scottish armour ‘three centuries old’.[31]

Comparing the spirit of Paterson’s paintings with those of his contemporary, Louis Buvelot, an Argus critic emphasised the way Paterson seized on the general effects of a scene, rather than on the detail and finish, and recommended Paterson’s broad and comprehensive method of looking at a given scene and arranging the ensemble of the constituent parts on the canvas. In 1884 Paterson exhibited paintings of the rural views around the Victorian township of Bacchus Marsh and Seymour, but also included a large view from Carlton Hill, Edinburgh, with the known beauty spots and architectural features of this view composed to situate Arthur’s Seat in the distance against the haze of the smoky atmosphere.[32] Suggestive of the mural panorama of Edinburgh on the vestibule wall at Villa Alba, this painting’s subject adds further to speculation that Paterson may have directed the composition of the mural. Paterson’s works in his Collins Street studio setting anticipated the paintings for which he became most famous: particularly his evocative, moody impression, Bush Symphony, painted in veils and flushes of harmonious pinks, lavenders, greens and delicate ochre shades, in 1900. Long under the influence of Whistlerian ‘art for art’s sake’, Paterson poetises the beauty of the bush scene with sonorous colour effects that resonate with the shades of Villa Alba’s interiors painted in the early 1880s.[33]

Lost treasures

Success after success followed for Paterson Brothers throughout the 1880s. The firm adapted and changed and new employees and designers worked under its umbrella, while Hugh Paterson travelled extensively abroad to gather new ideas and patterns. Although none of the firm’s work from this period is extant and no contemporary photographs have come to light, the archive reveals significant commissions awarded to Paterson Brothers for the art decorations of private and public interiors throughout Melbourne. With the success of Villa Alba behind it, Paterson Brothers issued an instructive advertising pamphlet in 1885, printed on softly toned paper, titled Decorative Art in Victoria, which spoke of their leading role in the rise and progress of interior decoration.[34] That same year, Hugh Paterson, under the banner of CS Paterson Brothers, designed and decorated Glen & Co.’s concert hall and gallery with painted medallion portraits of celebrity European composers. Along the arches, he depicted male and female characters taken from popular operas, painted in full length on a gold ground and, on the principal wall panel at the northern end of the large room, a scene from Beethoven’s Fidelio. Table Talk applauded his decoration as being the ‘necessary concomitants of “the establishment” in this age of aestheticism and the worship of the beautiful’.[35]

When Hugh Paterson left Australia for Britain in late 1885 with his friend and travelling companion, George Gordon, the Vice-Regal Consort, Lady Loch,[36] wrote letters of introduction to the pre-eminent arts and crafts designer, William Morris, artist Walter Crane and the Victorian Olympian artist, Frederic, Lord Leighton, President of the Royal Academy in London.[37] Paterson and Gordon enjoyed travelling together throughout Scotland, visiting the hills, and the places of their birth, and, as one report noted, ‘examining with a true artistic eye the treasury to be found in the art galleries and museums of London’.[38]

A scotch thistle centres each painted pilaster design beneath the gilt cornice. The current plain wall fills were painted with diapered Gothic revival foliage designs and featured a blue-green dado and burgundy-coloured diapered fill patterns. Evidence of these patterns is visible after recent conservation treatment of concentrated wall areas, but the overall scheme is waiting to be revealed.

photograph by Russell Winnell

In 1888 the Paterson Brothers’ expertise in the delineation of figures was acclaimed in Victoria and its Metropolis, published to promote the progress of the colony and to coincide with the upcoming 1888–89 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition. At the same time, Charles Paterson retired from the company and CS Paterson Brothers was dissolved. James and Hugh Paterson immediately reformed it ‘under the style of the Paterson Brothers, house painters and art decorators’.[39] Hugh Paterson’s talents as a figure painter were well known among the decorating trade in Melbourne; they had been used in the processional spectacles of the annual Eight-Hour demonstrations in front of Parliament House and throughout the streets of Melbourne. In 1884, for instance, he designed and painted the large silk banner for the Typographical Association’s horse-drawn lorry in the parade, illustrated with 15th-century scenes depicting William Caxton, the ancient ‘father’ of printing. Paterson based his composition on scenes illustrated in the black-and-white English illustrated journal, the Graphic. The richly coloured obverse of the resplendent banner inspired a certain Mr TL Work to poetry, recited at the fundraising event for the banner:

Scene first – The Abbey. From you blazon’d pane

Streams mellowed light upon the courtly train,

There Caxton stands, our patron wise and good. With conscious triumph in his attitude;

A man of modest yet triumphant mien.

He shows the first proof printed to his Queen.[40]

The reverse of the banner was equally impressive, depicting a large peopled interior of a Melbourne newspaper printery and office. Work’s poem ended resolutely: ‘Whate’er we lose when misery overpowers/ Retain inviolate the blest eight hours’.[41] In 1885, the firm was contracted to paint the large operative Bakers’ Society Banner, undoubtedly designed and painted by Hugh Paterson.[42]

Hugh Paterson’s talents in decorative figure painting were evident also to patrons of the new Palace Hotel in Bourke Street, decorated by Paterson Brothers in 1888. The promenade on the first floor featured large panels illustrating Shakespearian and Scottish figures painted on a gold ground, above a rich deep red and gold dado. The adjoining supper room was decorated with shades of amber, terracotta and blue and, in the spirit of Villa Alba’s decorations, subjects from Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley novels. The walls of the bar showed a rich design of pomegranates painted in gold, and the ceiling was ornamented in citron, amber, terracotta and gold lustre. In the grand dining and banqueting hall on the ground level, Hugh Paterson painted a large allegorical subject of classical muses around the proscenium of the hall’s stage. The Palace Hotel is long demolished.[43]

photograph by Russell Winnell

In 1888, spurred on by the promise of a whirl of grand, social events associated with the Centennial International Exhibition, Matthew Davies, the Speaker of the Legislative Council, commissioned Paterson Brothers to decorate Bracknell, Davies’ large, recently extended Toorak mansion. A combination of medieval, Gothic, Elizabethan and Pompeian stylised ornamentation, the art decorations featured circles containing family portraits on the dining-room ceiling and a frieze segmented by panels showing scenes from The Golden Legend, The Spanish Student, Miles Standish and Evangeline, and smaller panels depicting historic portraits. All the figure subjects at Bracknell were painted by Hugh Paterson, including the Chaucerian characters depicted on the rich gold frieze circumscribing the main entrance hall. Ensembles of motifs relieved in gold were orchestrated in deep, rich colours and these vibrant Eastern tints and tones of the walls and ceilings harmonised, according to reports, with the damask textiles, hanging Liberty silks and furniture especially selected – with advice from the Paterson Brothers – by Mrs Davies.[44] Paterson was assisted in the work by another Scotsman, John Ross Anderson,[45] and the art decoration at Bracknell achieved the accolade of being reported in the prestigious English Journal of Decorative Art, well known among Australian architectural and professional decorating circles.[46]

Paterson Brothers’ decorative work on the interior of Government House in Melbourne, the Victoria Club and other commissions continued to receive the attention of the press until the firm folded in the 1910s.[47] Decorative costumed figure paintings by Hugh Paterson for friezes remained a speciality and the firm painted a lush, verdant and colourful tropical forest scene around the exterior of the large new large aviary at Melbourne’s Zoological Gardens in 1891.[48] In the late 1880s, the art decorator and instructor TS Monkhouse became a leading designer for the firm, and specialised in ornamental motifs. As well as continuing his decorative figure work, Hugh Paterson oversaw the company with James and exhibited his oil paintings at the Victorian Artists’ Society exhibitions. He exploited his talent further in his many costume designs for stage productions, especially at the new Princess Theatre in Melbourne, the interiors of which had been decorated by George Gordon in peacock blue, cream and gold.[49] Monkhouse, a friend of Charles Paterson through the latter’s role as a leading Council member of the Working Men’s College, directed Paterson’s decorative scheme for his famed Grosvenor Chambers building in Bourke Street-east.[50] The enterprising Charles Paterson built these chambers expressly to house artisans’ workrooms and artists’ studios, including one for Tom Roberts, who painted Paterson’s portrait in 1888 and exhibited it at the 1888 Centennial Exhibition.[51]

Enduring friendships

After the decoration of Villa Alba was completed, William Greenlaw maintained his friendship with the Patersons, particularly Charles Stewart Paterson, with whom he speculated in some seemingly spurious land deals and syndicates around Fern Tree Gully.[52] Charles Paterson took up residence at Studley House, adjacent to Villa Alba, in the late 1880s. Greenlaw also maintained a long friendship with the younger siblings, James and Hugh.

A year after the decorations at Villa Alba were completed, Greenlaw attended the annual dinner of the employees of Paterson Brothers at the Trades Hall, recently decorated by the firm, and expressed his conviction that Paterson Brothers were leading the way in advocating by example the importance of decorative art ‘in the minds of the people’.[53] Essentially a high-spirited Scottish affair, this annual dinner was enlivened by the music of a Highland piper, and a bodyguard in full Highlander dress, who performed Scottish national dances. A leading member and chairman of the intercolonial Draughts Players Congress, Greenlaw often met Charles, Hugh and James, the champion of Australasia, to play draughts and socialise together at the Melbourne Draughts Club. And at the Centennial Draughts Congress in 1888, a landscape painted and donated by John Ford Paterson was a winning prize in the competition.[54] That John Ford Paterson continued to be involved in the painting of backdrop scenes for Melbourne theatre productions at the beginning of the land crash to earn money seems almost certain, but he was also friends with Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts’s circle through the Victorian Artists’ Society. Streeton, whose paintings were patronised by Hugh Paterson, wrote to Tom Roberts in 1892 about John Ford Paterson’s imminent departure for Scotland: ‘JF Paterson who is one of the faithful properties of the Gallery Eastern Hill – is leaving for a trip to England or Scotland (“Ba Gord Scene paintin’s a mechanical art Ba Gord”)’.[55] And a year earlier, Hugh Paterson visited his friend George Gordon, who was working between Melbourne and Sydney as a scenic designer and painter at the Theatre Royal in Melbourne, in the company of Streeton.[56]

photograph by Russell Winnell

Although the reported scandals of suspect land syndicate deals around Fern Tree Gully shadowed Greenlaw’s and Charles Paterson’s speculative interests, life at Villa Alba continued well enough over the next few years, before the 1890s brought the inevitable financial crash and economic depression, of which William Greenlaw was literally and figuratively a fatality.[57] Reports of his death in 1895 appeared in Melbourne and Sydney papers, and prior to the sale in 1897 of Villa Alba’s furniture and objets d’art collected by Mrs Greenlaw, the Gippsland Times baldly noted Greenlaw’s demise:

Poor old Mr Greenlaw was killed by the bank crisis. He got inflammation of the lungs and his private affairs were so smashed up that he was rather glad than otherwise to die. Villa Alba was the pride of his heart, and he spent huge sums over its decoration and furnishing.[58]

Villa Alba: a museum without a collection?

Villa Alba Museum (house and garden[59]) in Walmer Street, Kew, is open to the public on the first Sunday afternoon of each month, between 1 pm and 4 pm. Entry proceeds assist the building and garden landscape maintenance, and the ongoing expert restoration of the interior’s splendid painted schema – a work in progress.

In the late 19th century, visitors would have travelled by carriage, or taken the Simpson’s Road ferry across the Yarra. Today, if not driving, the best way to get to Villa Alba is to take the tram down Victoria Street from the city and cross the snaking Yarra River on the footbridge. Stroll up the gentle slope of Walmer Street, and the large iron gates of the villa are on the right hand side of the street towards the crest.

Simpson’s Road is now Victoria Street, and the track leading up to the house on the top of the hill to the right is now Walmer Street, formerly Studley Ferry Road, from the bridge’s current overpass. The building at the top of this road track is most likely the original Villa Alba. The engraving was reproduced in 1873 from an album of wood engravings exhibited at the 1873 International Exhibition, London, by the Commissioners of the colony of Victoria to the exhibition.

National Library of Australia

Painted and stencilled interior decorative schemes during the late Victorian period were de rigueur for the rich and aspiring, but over time they were painted over, or destroyed by the rampant demolitions in the name of progress and modernising development throughout the 20th century. At Villa Alba, much of the original wall decoration was whitewashed when the site was transformed into a women’s hospital in the 1950s.

Ongoing government funding, including a few substantial project grants, have assisted greatly in the conservation work, and in mid-2012 an application for a local heritage grant through the Australian Government, for the final restoration of the interior’s vestibule murals, was successful. (Applications for returning schemes in some other rooms were not.) Such a grant recognises the house’s national heritage significance.

The presentation and interpretation of historic house museums often rely on permanent object collections to set-dress, conjure stories, evoke cultural memories and associations, and shed light on patterns of consumption, family life and social structures. The layout and spatial configurations of such houses, their outbuildings and landscaping, might suggest social hierarchies and patterns of life, leisure and labour during the houses’ significant periods of occupancy. Objects are the silent actors in these stories and, if none or few survive from the selected period(s) under interpretation, they may be acquired by museum managers to help recreate the gardens, interiors, and outbuildings according to the fashions of the period, the effects of time passing, the workings of the house, and the occupants’ aspirations, social milieu, class and tastes. Villa Alba is different. This house museum is, instead, an open book of architectural interior enrichment created during the 1880s in Melbourne. The site, incorporating the garden and the building, its fabric and fitments, is the museum artefact. Villa Alba’s splendid, eclectic decorations are the house museum’s developing collection. The decorations ornament ‘period rooms’ that hold no other objects except for the original overmantel in the drawing room. Perhaps for this very reason, this particular museum will survive the vicissitudes and changing fashions that affect the presentation of art museums and historic houses, such as those that occurred in the second half of the 20th century, as fashions in interpretation and curatorial attitudes to collecting and heritage changed.[60]

photograph by Russell Winnell

Conclusion

The art decoration at Villa Alba is a rare example, not only of an ambitious and patriotic Scotsman’s regard for his wife, his place of birth and his social position, but also his patronage of the Scottish Paterson brothers. Today these art decorations form the only surviving example of this firm’s work. It is an art form long erased but once famed in the interiors of suburban Melbourne mansion interiors during the 1880s and into the 1890s. This historic house and precinct comprise a significant cultural heritage artefact, and future work will uncover more of its obscured painted past, executed during Melbourne’s most wealthy colonial period.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes

1 Only one interpretative article (Jessie Serle, ‘Greenlaw’s folly: Villa Alba’, Australian Antique Collector, no. 45, Jan–June 1993, 40–4) has been published specifically on the villa and that was in the early 1990s. More recently, this house museum has attracted promotional reportage that construes its interior ornamentation sensationally as Victorian boom time extravaganza, see ‘Extravagance revealed’, Antiques and Collectibles for Pleasure & Profit, no. 42, Spring 2011, 66–9.

2 The change of name had been effected by the time the Greenlaws placed an announcement of the birth of a daughter in the Argus, 18 December 1867, p. 4.

3 Announcements of the births of the Greenlaws’ first and last children are in the Argus, 31 August 1863, p. 4, and the Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 28 January 1874, p. 14.

4 Miles Lewis, ‘The Villa Alba: A reappraisal’, [Report on fabric from the pre-1856 house], October 1997, p. 12, cited in Michele Summerton & Ros Coleman (comp.), The Villa Alba Conservation Management Plan, Villa Alba Museum Incorporated, 2008, p. 40; Argus, 3 March 1882, p. 4; Argus, 8 January 1880, p. 4.

5 John Mather and the English firm of Gillow decorated Clarke’s residence in 1878.

6 ‘A splendid mansion’, Table Talk, 26 June 1885, p. 4.

7 ‘Heraldry, monograms, graffiti’, in Kosinova Thorn, ‘An investigation of the interior decoration’, 1986, cited in Summerton & Coleman (comp.), The Villa Alba Conservation Management Plan, p. 62.

8 George Augustus Sala, ‘The Land of the Golden Fleece: VII – Marvellous Melbourne’, Argus, 8 August 1885, p. 5.

9 ‘Private house decoration’, Argus, 15 May 1880, p. 5.

10 ‘Art decorations for dwellings’, Argus, 4 August 1881, p. 10.

11 ibid.

12 The company was known as Paterson Brothers or Paterson Bros in the 1870s (see ‘Paterson Bros, 3 Elgin-street, Carlton, Melbourne’, Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 (Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition 1875), Official Record, McCarron, Bird & Co., Melbourne, 1875, p. 135). In 1883 the firm of Scots-born siblings registered their formal partnership as CS Paterson Brothers, operating from ‘1 Little Collins Street-west, Melbourne’: Argus, 5 November 1883, p. 3. Charles Stewart Paterson, the oldest of the siblings, retired in 1887 and the company reverted to Paterson Brothers (or Bros). To reduce the potential for confusion, throughout this article I will refer to the company as ‘Paterson Brothers’.

13 Andrew Montana, ‘The cosmopolitan soul of architecture: Interior art decoration in late nineteenth-century Australia, and the legacy of Owen Jones’, Fabrications: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand, February 2012, 8–36.

14 Summerton & Coleman (comp.), The Villa Alba Conservation Management Plan, p. 89.

15 Like ‘trompe l’oeil, the effect of deceiving the eye into believing that a painted surface is an actual scene.

16 ‘A splendid mansion’, Table Talk, 26 June 1885, p. 4.

17 ibid.

18 Two ornate chandeliers, sourced from Denton’s antique chandelier and wall lighting specialists, London, have recently been installed in Villa Alba, in the drawing room and in the principal bedroom: information courtesy Andrew Dixon.

19 Rizzi’s flower paintings were commended when he assisted with the domed ceiling decorations of businessman and politician John Halfey’s now long-demolished Kew mansion, Orsdall, several years earlier under the direction of another Melbourne decorating, manufacturing and retail firm, Cullis Hill & Co., best known for its decorations of the famed 9 x 5 Impression Exhibition in Melbourne in 1889.

20 This was not in itself unusual. A Scottish flavour is also seen in the large stairway-landing window at the Italianate mansion, Werribee Park, built in the late 1870s outside of Melbourne for another wealthy Scottish immigrant, Thomas Chirnside. But whereas the Werribee Park window’s etched glass pane depicts Sir Edwin Landseer’s famous 1850s painting Monarch of the Glen, a favourite of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the decorations at Villa Alba mix the modern Aesthetic and Artistic idioms, fashionable a generation later throughout Britain, North America and Australia.

21 ‘John Ford Paterson’, Table Talk, 25 July 1901, p. 16; ‘Art at home’, Daily Telegraph, 3 March 1884, p. 7. John Ford Paterson had lived and worked in Scotland from the mid-1870s, and was influenced by the emerging Glasgow School’s style of decorative, tonal naturalism in painting.

22 Gordon advised Robert Reid’s art decorations for the interior of the city of Melbourne’s banking chamber in the ‘Renaissance’ style in 1888, for which he was applauded (‘Progress of decorative art’, Argus, 9 July 1888, p. 8). Such was the Scots nexus of artists in Melbourne at this time. Further, Hugh Paterson painted and exhibited a portrait of Gordon at the Victorian Artists Society Exhibition in 1888, which included many paintings by his brother John Ford Paterson, and the Paterson Brothers advertised the art-decorating firm in the catalogue for the Society’s exhibition held at the National Gallery of Victoria in May 1888 in Melbourne: ‘Paterson Bros. House Painters & Art Decorators’, Victorian Artists Society Exhibition, May 1888, Grosvenor Gallery, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, p. 24.

23 Gordon worked in the English theatre scene during the mid-1870s, where he was instructed in the ‘archaeological accuracy’ of Shakespeare’s sets and costumes by actress Ellen Terry’s husband, the architect and designer EW Godwin. See Barbara Hodgdon & WB Worthen (eds), A Companion to Shakespeare and Performance, Blackwell Publishing, Malden and Oxford, 2005, p. 243; Ixion, ‘George Gordon’, Australasian, 17 June 1899, p. 1325.

24 ‘Art in the theatre’, Argus, 25 May 1885, p. 7.

25 Elizabeth Prettejohn, Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2008; ‘Messrs. Paterson Bros.’, Australasian Decorator and Painter, 3 November 1909, 20–30.

26 Argus, 14 June 1884, p. 9.

27 Catalogue of Superb and Costly High-Art Furniture … Collected by Mrs William Greenlaw, Villa Alba, Studley Park Road, Kew, Gemmell, Tucket & Co, Melbourne, 22–23 March 1897.

28 Australian Town and Country Journal, 16 February 1889, p. 35.

29 Unidentified newspaper cuttings, Paterson Family Papers, MS 6882 Series 1, Folio Box 2, National Library of Australia manuscripts collection.

30 ‘Art in Melbourne’, Once a Month, 15 October 1885, p. 312.

31 ‘J. F. Paterson’, Table Talk, 3 August 1889, p. 5.

32 Argus, 4 October 1884, p. 4.

33 Illustrated in Lyn Johnson, ‘Introduction’, John Ford Paterson: A Family Tradition, exhibition catalogue, McClelland Gallery, Langwarrin, 2010, p. 2.

34 Argus, 3 October 1885, p. 13.

35 Table Talk, 16 October 1885, p. 16; ‘Concert at Glen’s Rooms’, Argus, 16 October 1885, p. 6.

36 Paterson Brothers’ business card boasted of the firm’s special appointment to His Excellency Sir HB Loch. Lady Loch was highly regarded for her promotion of advanced art and modern ornament in Melbourne’s elite circles. Her public spirit in raising taste within the community is exemplified in her request to Leighton to select about 30 examples of fine ceramic art from Morris & Co. and the annual exhibition of porcelain and pottery at Howell & James’, London, for the National Gallery of Victoria, funded through a £100 grant from the Gallery’s Trustees. ‘Art in Melbourne’, Once a Month, 15 February 1885, p. 136.

37 Morris was known primarily in Australia as a pattern designer for textiles and wallpapers, and Crane as a painter, decorator and illustrator, whose babies’ books may well have inspired the nude ‘putti’ figures playing sport, taking photographs and generally larking about along the upper frieze of Villa’s Alba’s entrance hall. For example, Walter Crane’s Baby’s Bouquet, George Routledge & Sons, London, 1878.

38 ‘Our London correspondent’, West Australian, 28 October 1886, p. 3. Leaving London for Australia in mid-August 1886, Paterson and Gordon travelled with the new theatrical troupe assembled in London by Robert Brough who with Boucicault jnr was the manager of the Melbourne Opera House. Along with the troupe, William Spong, the well-known scenic artist, was on board ship: Argus, 21 October 1885, p. 7.

39 ‘Paterson Bros, Melbourne’, Alexander Sutherland, (ed.), ‘The colony and its people in 1888’, Victoria and its Metropolis: Past and Present, Vol. 1, McCarron, Bird & Co, Melbourne, 1888, p. 615; Argus, 10 September 1887, p. 15.

40 ‘Melbourne Typographic Association’, Argus, 12 April 1884, p. 8; ‘The Eight Hours Demonstration’, Mercury & Weekly Courier, 12 April 1884, p. 3.

41 ibid.

42 ‘Trade Society meeting’, Argus, 23 March 1885, p. 6.

43 ‘The Palace Hotel’, Argus, 21 December 1888, p. 11.

44 Andrew Montana, The Art Movement in Australia: Design, Taste and Society 1875–1900, Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Melbourne, 2000, pp. 76–9; ‘An artistic residence’, Herald, 11 December 1888, p. 4.

45 Anderson had recently worked with the Sydney-based art decorating firm Lyon, Wells & Cottier, managed by Scots émigré John Lamb Lyon, on the splendid Aesthetic interior decorations of the English, Scottish and Australian Bank and upstairs manager’s residence in Collins Street, Melbourne.

46 ‘An ornamental colonial interior’, Journal of Decorative Art, May 1889 (p. 74).

47 Charles and Hugh Paterson both died in 1917.

48 Argus, 4 June 1891, p. 9; In some of their interior art decorating work, Paterson Brothers used the newer fashion for Sanitary, Japanese and gilded embossed papers to compliment the hand painting and stencilling of ceilings, dados and friezes; this newer mode of wallpaper treatment grew in popularity well into the 1890s when the dado went out of style, see ‘Interior decorations’, Building and Engineering Journal, 15 June 1889 (p. 442).

49 ‘Romeo & Juliet’, Argus, 30 June 1890, p. 8.

50 ‘A successful artist: Mr C. S. Paterson’, Table Talk, 27 April 1888, p. 12.

51 Helen Topliss, Tom Roberts 1856-1931: A Catalogue raisonné, Vol. 1, Text, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1985, cat. no. 110, p. 105.

52 ‘A land syndicate transaction’, Argus, 15 August 1889, p. 9.

53 Melbourne Bulletin, 23 November 1885, p. 6.

54 The newly decorated chambers are illustrated in Montana, The Art Movement in Australia, p. 73; ‘Centennial Draughts Congress’, Argus, 23 November, 1888, p. 8.

55 Letter, Arthur Streeton to Tom Roberts, late May 1892; in Ann Galbally & Anne Gray (eds), Letters from Smike: The Letters of Arthur Streeton, Oxford University Press, Australia, 1989, p. 51.

56 Letter, Arthur Streeton to Tom Roberts, [undated month], 1891; in ibid., p. 32.

57 Advertiser (Adelaide), 14 August 1889, p. 4; Argus, 26 July 1889, p. 5.

58 Gippsland Times, 22 March 1897, p. 3. Because Villa Alba was in Anna Maria Greenlaw’s name, her occupation of the property was not initially affected by her husband’s insolvency.

59 Today, Villa Alba stands in a small, recreated ornamental garden. In 1885 the land size was nearly two acres (0.8 hectares) and this increased until the early 1890s through Greenlaw’s purchasing of surrounding land subdivisions. When it was purchased by Mount Royal Hospital in 1974, its exact land size was ‘1 acre, 2 roods and 33.1 perches of land’ (just under 0.7 hectares): Summerton & Coleman (comp.), The Villa Alba Conservation Management Plan, p. 30.

60 Julius Bryant, ‘Museum period rooms for the twentieth century: Salvaging ambition’, Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 24, no. 1, March 2009, 73–84. A public historic house museum without a recreated setting of objects based on documentary evidence was anathema to emerging, professional historic house museum curators in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 1981 architectural historian and curator James Broadbent advocated a departure from the predilection for ‘nostalgia’ interiors of well-meaning National Trust volunteers. In distinguishing the role of the then new Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales from decorative arts museums, Broadbent advocated the presentation of a historic house interior based on physical evidence and documentary primary research and the comparative interpretation of social classes and patterns of consumption. See, ‘Historic house museums: A talk given by James Broadbent at Vaucluse House on May 18, 1981 to celebrate International Museums Day’, Historic Houses Newsletter, July 1981, 3–13.