The Finsbury cabinet-makers Smee & Sons in colonial Australia

by Andrew Montana

Messrs. William Smee and Sons, of Finsbury Pavement, London are large exhibitors of furniture in which elegance is combined with utility; it is not of the costliest character, but is remarkable for judgement and taste in design and excellence in workmanship.

Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1862[1]

The prominent wholesale and retail cabinet-making firm, Smee & Sons, Finsbury, London, has never been a subject of scholarly enquiry in Australia, or brought into perspectives on the study of colonial Australian middle-class interiors and furniture. Extant examples of Smee furniture today are scarce, yet the furniture and patterns of this firm had an enormous impact throughout the Australian colonies during the nineteenth century. It is, in fact, remarkable that the company’s significant presence and widespread influence in the Australian colonies have not been realised or documented.[2] Arguably as popular in Australia as the prestigiously brand-named pianofortes from London and the Continent imported into Australia for the middle-class parlour and drawing room, or Alcock & Co.’s billiard tables manufactured in Melbourne for the smoking room and library, Smee’s furniture was imported in shiploads to the colonies, as evidenced by the many auction, import and advertising listings this article sources and evaluates. Unlike other furniture brands, often advertised anonymously, the Smee name features prominently in Australian auction and import notices. Smee & Sons also participated widely in international exhibition displays. The company displayed furniture styles for middle-class domestic interiors in these exhibitions, and middle class aspirations, desires and patterns of consumption were publicly showcased within these spectacular arenas of mid to late Victorian modernity.

While a few historians have recorded that Smee furnished particular mansions in New South Wales and Victoria in the mid-Victorian period, this paper reveals that Smee formed a major part of the furniture collections in many mansions and villas in these colonies, and that the company had a long-standing influence in Tasmania and South Australia, as well as a more modest presence in Queensland.[3] Moreover, throughout the century, Smee & Sons produced more than the two pattern books and the catalogues dating to about 1850 and 1870 for which they are most known in Australia. It also seems likely that a first edition of the earlier catalogue was published in the late 1830s and circulated in Australia during the early 1840s in tandem with John Claudius Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture (1833), before the economic crash curtailed the opulence of colonial merchants, ‘merinos’ and parvenus alike.[4] What will be certain from this paper is that another pattern book showing ‘700 new designs’ was advertised by Smee and circulated around the Australian colonies to coincide with the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition and its rival in Melbourne, the 1880 International Exhibition.

Smee exhibited at major international exhibitions: in London in 1851, Paris in 1855, London in 1862, and again in Paris in 1867 and 1878. The company not only exhibited at Sydney’s 1879 International Exhibition but was also acclaimed for its exhibits at the 1888 Centennial International Exhibition extravaganza in Melbourne. Styling and manufacturing quality furniture for the established and growing affluent middle classes, Smee sold to importers, retailers and cabinet-makers, who, in turn, resold the furniture or copied and modified styles from Smee’s catalogues. Smee used quality timbers and kept a wide range of stock patterns throughout the decades. It exploited the visibly changing patterns of selling and consumption and the new technologies facilitating production and market distribution throughout the Victorian periods. Quickly identifying and supplying markets throughout the nineteenth century, Smee provided its customers with a wide range of patterns that reflected eclectic interior styles and a growing interest in shopping for changing novelties. As the population and the social and economic importance of London grew for British consumers, colonial Australian importers, cabinet-makers and gentry identified with Smee’s rising reputation and ordered or consigned furniture from its London establishments and consulted its pattern books.

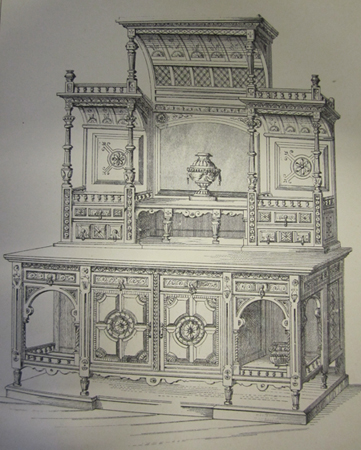

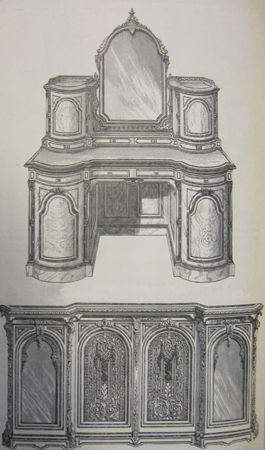

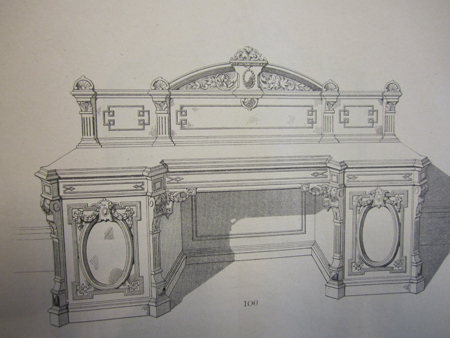

Caroline Simpson Research Library, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

More stylists than innovators in furniture design, Smee & Sons nevertheless led, as much as it reflected, the tastes of the middle classes during the century of capitalist expansion throughout the British Empire. The growth in the number of cabinet-makers in Britain and Australia and the rise in the importation of British furniture and furnishings to the colonies during the second half of the century, in tandem with immigration, population expansion and increasing salaries would have cemented the economic and cultural importance of Smee’s product.[5] The company supplied household consumers, businesses, hotels and the trade. It maintained competitive payment systems that varied according to the clientele, preferring fast cash to terms of credit with reference, and took as much pride in its lower priced articles as its ‘superior’ ones. Customers could request modifications to a model seen in the showrooms or in the catalogues, thus ensuring that the articles were ‘made either less or more expensive if needed’.[6] Historicist in styling, whether modern Greek, Gothic, Tudor and Elizabethan, rococo, or Renaissance, much of Smee’s furniture was characteristically early to mid-Victorian, and featured carved and incised details, ormolu galleries, inlaid panels, turnings, trusses, curves and cabrioles, ornamental aprons, contrasting mouldings, medallions, French polishing, and japanning. These details might reflect the mouldings and details of an interior, including cornices, ceiling enrichments, fireplace surrounds and even decorative curtain hardware.[7]

Private collection

Smee cleverly modernised some of its ranges during the late 1860s and into the 1870s. In line with the changing fashions sought by younger consumers and in competition with the art furniture being produced by English companies including Gillow, William Watt, and Collinson & Lock, simpler rectilinear and architectonic forms sometimes replaced bombé and curvaceous ones. Smee also adapted its range in response to publications such as the well-advertised and influential household guide, Hints on Household Taste (1868) by Charles Locke Eastlake, which was aimed at the new middle classes and promoted the reformed Gothic and medieval styles.[8] But these new styles were being produced in tandem with the stock-in-trade historicist lines and furniture bearing ersatz armorial carvings for the new rich seeking the trappings of ancestral lineage.[9] Creating designs in the Early English and Anglo-Japanese styles from the mid-1870s, Smee employed well-known art architect and designer Edward William Godwin in or before the early 1880s.[10] Recently surfacing in Hobart, for example, an elegant, ebonised mahogany and hand painted drawing-room writing table, stamped ‘W. A. & S. Smee’, dates precisely to 1877. In the cutthroat world of cabinet-making styling, Smee sold on their patterns as a means of maximising revenue. A variant of this table was manufactured by R Hunter in Hampstead, London, and illustrated in The Cabinet-Makers’ Pattern Book: Being Examples of Modern Furniture (1878).[11] Such was the pervasive reach of style exploited by Smee in Britain and in Australia by cabinet-makers and wholesalers, who were often quick to copy and vary styles according to their markets.

Private collection

Early days: from funerals to furnishings

The firm of William Smee & Sons goes back to the 1820s when it was operating from Moorfields and nearby Finsbury in North London.[12] Finsbury was well known in the mid to late eighteenth century for the resident practices of doctors and, by the early nineteenth century, for the number of dissenters and members of the Society of Friends (Quakers) who lived there. The founder of the Religious Society of Friends, George Fox, was laid in the old Quaker burial ground near Bunhill Fields, Finsbury, and it is almost certain that William Smee was from a family of Quakers. A large number of Smees living at Finsbury Circus during the nineteenth century were Friends, and had established interests and careers in banking, physics, the natural sciences, humanism and philosophy.[13] Indeed, the company of William Smee & Sons, Finsbury Pavement, London, frequently advertised in the organ of the Society, the British Friend, which commenced publication in the early 1840s.[14]

Many Quakers believed in productivity and progress and looked to manufacturing and engineering as profitable enterprises, as advertisements directed at capitalist ‘Friends’ in the British Friend indicate. In 1866 architect Alfred Waterhouse, well known for the design of Manchester Town Hall and the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, designed ‘Messrs Bassett and Co.’s’ Quaker Bank (later Barclays Bank) in Leighton Buzzard, England, in the Ruskinian reformed Gothic style. Smee executed the oak, mahogany and ebony fittings.[15] But whatever the Smee clan’s religious affiliations around Finsbury, William Smee & Sons operated as property valuers and agents from the 1820s and made and upholstered coffins and acted as funeral directors for the Society of Friends.[16]

With rapid changes in the growth, affluence and expectations of consumers, and the expanding railway networks around Great Britain that transported shoppers and merchandise, the marketing of furniture and furnishings to meet consumer demands was imperative in the competitive world of the furniture, furnishings and upholstery trades. The crafting of bespoke furniture for a relatively local market became a thing of the past. Moreover, as British colonial customers became wealthier, they fed their aspirations through purchases from London-based firms, including William Smee & Sons, which supplied furniture, brassware and soft furnishings from at least the late 1830s. By 1867, the undertaking side of the Smee business was relinquished and the company concentrated on its property agency and valuation business and its spawning furniture manufactory and showrooms at Finsbury.[17]

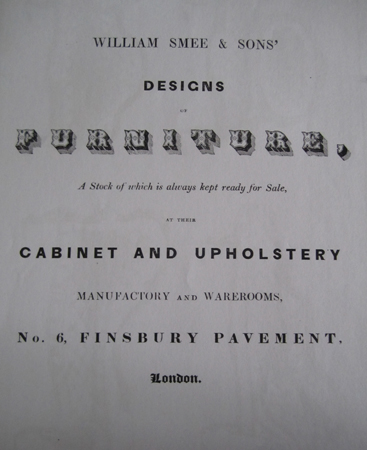

Designs for furniture

As the century progressed, there was a growing commercial imperative to produce manufacturers’ catalogues, advertising a wide range of merchandise, services and styles.[18] Designs of Furniture, the first known major catalogue produced by Smee, dates from the mid to late 1840s, some years before the company exhibited at the Great Exhibition of All Nations in London in 1851.[19] It was probably produced (or reissued from an earlier edition) with this huge exhibition in mind and the trade it was designed to generate; Smee was one of the furniture firms included in the pages of the Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue, compiled to advertise the art industries of the Great Exhibition. And in the Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue for the 1862 Exhibition in London the company’s display was noted for ‘judgement and taste in design’ without being of ‘the costliest character’.[20] The furniture illustrated in the Art Journal and the company’s catalogues exemplifies the ways in which Smee popularised the gamut of historical styles that appealed to the early and mid-Victorian markets.[21] Confirming the influence of Blackie and Son’s The Cabinet-Maker’s Assistant (1853), Smee’s design details were often hybridised from an eclectic repertoire, characterising much of their furniture in a variety of timbers — predominately oak, rosewood, walnut and mahogany — during the middle-decades of the nineteenth century.[22]

State Library of Victoria, Melbourne

Decorative effect and the technological modernisation of production were Smee’s fortes. Ostentation fed the desires of new wealthy consumers and satisfied their urge for display under the guise of utility. An oak dinner-wagon in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum is a case in point. It appears to be a conventional turned and carved side table but, when the top is raised, three leaves extend at intervals and the side table is transformed into a ‘running footman’, suitable for serving meals in a small room. Another ‘invention’ illustrated in an early catalogue is an ottoman that folded out firstly to make a chair, and then to make a bed. Throughout the Victorian period, Smee’s designs catered for the new daily rituals and mores of the growing middle class. Smee’s wholesale and retail furniture was typically directed to the purses of men. Manuals and guides on home management, domestic economy and artistic taste aimed at middle-class women proliferated from the 1850s, but until the later 1870s, in Britain as well as the Australian colonies, the home’s furnishing, apart from the decorative touches, was the preserve of the home’s ruling ‘master’, epitomised in architect Robert Kerr’s guide The Gentleman’s House (1864).[23]

Furnishing the home was both the bane and the privilege of a gentleman who sought to impress his new wife with his ‘castle’. Seeking an ancestral claim through the ‘baronial’ trappings of his furniture, the mid-Victorian male often performed his chivalric code of conduct through the acquisition of fashionable furniture.[24] And the wide range of revival styles offered through Smee’s catalogues guided the selection, thus associating the patriarch and his family with a lineage and past. This habitude was accelerated by the second wave of the Industrial Revolution; it acculturated and defined Victorian family domestic life, based on property ownership, kinship and, not least, a man’s social standing.

Smee’s styles in the Australian colonial context

When author, journalist, and international exhibition official Richard E Twopeny penned his observations about taste in domestic furniture across classes, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, he sniffed about the attraction of the new rich ‘Croesus’ and ‘Mutton wool’ for ‘deformed’ rococo revival silhouettes and frames in parlour and drawing room furniture. Smee manufactured these styles from early mid-century and they remained popular in Australian interiors until the Aesthetic fashions of the last three decades modified, or mixed with, these historicist forms, and the gaudy tones and bright colours of mid-Victorian upholstery were generally quietened. Reflecting a generational change in attitudes to new styles, the rising and influential flood of Japanese decorative arts, and the commercial expansion of stores into department stores, the popular Aesthetic fashions in furniture were lighter in appearance and structure with recognisable hints of Japanese, quaint Early English and Queen Anne design elements. An eclectic medley of chairs and occasional tables in these hybrid styles dressed drawing rooms and boudoirs and contrasted with the formal, lugubrious and French polished mahogany and walnut matching furniture suites from the earlier period. In the early 1880s Twopeny focused on the spending patterns of the ‘head of the house’ and he noted that several Australian millionaires had ordered their suites from prestigious and well-known English companies such as Jackson & Graham, and Gillow. As for the strong middle markets, he generalised that:

many colonists who go on a trip to England bring back with them drawing and dining room suites; but even then there is an entire want of individuality about the Australian house — which is the more remarkable seeing how much his [the Australian male’s] individuality has been brought out by his career, and shows itself in his general actions and opinions.[25]

Private collection

Twopeny’s assertion homogenises the ‘Australian house’, but some of the cultural baggage he identifies most probably came from Smee, and his account suggests a similarity in the taste for furniture between the English and the Australian middle classes during the second half of the century. Davenports, loo tables, sideboards, washstands, and dining room, drawing room and bedroom furniture serviced the daily rituals of that major institution evolving throughout the nineteenth century: the patrician middle-class family. The spaces designated as public and private, or masculine (the smoking room, library, dining room and billiard room) and feminine (the parlour, drawing room and boudoir), were made public in exhibitions, warehouse and shop displays. Established through rising capitalist industries, technologies, and a new nexus of commodity exchanges, the middle-class family occupied a central position in the organisation and definitions of public and private life, the separation of which was increasingly blurred in the commercial worlds of display and advertising.

Owning Smee furniture positioned the patrician at the forefront of colonial success; its possession represented status and showed that the demands of colonial enterprise were rewarded with solid furnishings, comfort and luxury. Such was the case in Sydney when Robert Porter, Esquire, auctioned the contents of his Darling Point harbourside villa, Carthona. Originally built for surveyor-general Sir Thomas Mitchell in the domestic Gothic style between 1841 and 1844, and fashioned after a plate in John Claudius Loudon’s popular and well-thumbed pattern book, Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture,[26] the house and contents fell under the hammer in 1853: ‘The whole of the furniture was made expressly to order, by the justly celebrated manufacturers Messrs. Smee & Sons, Finsbury-square, London’ proclaimed the auction notice ‘and has only been in use twelve months’.[27] Porter had acquired hall, dining room, drawing room, breakfast and bedroom furniture from Smee, most of it made in rosewood, Spanish (Cuban) mahogany and English mahogany.

Large numbers of auction notices advertising the sale of Smee furniture indicate its popularity in New South Wales during the second half of the century as the economy revived and the gold rushes generated optimism and enterprise. The notices clearly indicate the pull of the Smee brand name in furniture. At Albion Wharf in 1853 a large consignment of Smee furniture was auctioned and at Circular Wharf in 1854 a large sale included a shipment of marble top washstands from Smee.[28] In January 1856 Frith and Payton announced the sale of 35 cases of ‘Elegant and Substantial Furniture’ from Smee & Sons from a local importer to ‘cabinetmakers, upholsterers, private families, hotel keepers and others’, and in February 1858 the same auctioneers announced the sale of 87 packages of drawing, dining, bedroom furniture and bedding invoiced from ‘the celebrated house of Smee & Sons’. The shipment included chimney and pier glasses and toilet and cheval mirrors.[29]

By the late 1850s, PF Morgan selected his entire range of furniture from Smee for Enmore Lodge, Newtown, and in 1860 ‘Gentleman, upholsterers, furniture buyers and the trade’ were invited to inspect the latest shipment of furniture from Smee & Sons, London. The same year, the sale of DP McEwan’s ‘truly elegant and substantial furniture, personally selected from the celebrated manufactory of Messrs Smee and Sons, London’, at his residence Linthorpe, Newtown, was advertised prior to his return to England.[30] McEwan’s drawing room furniture alone comprised a suite covered in green and gold, and included eight chairs, two easy chairs, a lounge, ottomans, and a davenport, a whatnot, a worktable, a loo table, a chiffonier, and occasional chairs — ‘all of the latest design’ by Smee. In February 1860, 21 packages of Smee furniture were auctioned, while in May, Thelkeld and Co. auctioned Randolph Nott’s collection of furniture including a Spanish mahogany bedstead made by Smee, ‘with spring mattress complete’. In July, an office desk by Smee was auctioned with Henry Jeffrey’s collection of furniture. In February 1862, a suite of dining-room furniture upholstered in morocco was advertised for sale with a large Turkey carpet at Aspinwall and Co., Sydney. And by the later 1860s, Smee had furnished JM Leigh’s Macquarie Street residence.[31]

Caroline Simpson Research Library, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

Who was setting this taste for Smee furniture: the auctioneers, the gentlemen who selected their furniture from Smee, or the company itself? As Australian colonial furniture specialists Kevin Fahy and Andrew Simpson have recognised, the company’s pattern books, especially Designs for Furniture, were a source of influence on colonial cabinetmakers.[32] Copies of the earliest catalogues have been located in Hobart, north Tasmania, and Adelaide, while the State Library of Victoria also holds a later edition of an early catalogue.

Robert Griffith’s important article on the influence of English pattern books on Australian colonial furniture design records furniture in the Rouse Hill House collection, owned and managed by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, based on Smee’s catalogue or secured from the firm’s stock by Sydney retailers and manufacturers. The style of the teapoy (a three-legged table) in the Rouse Hill collection is from Smee’s circa 1850 catalogue, and is one of many drawing room pieces purchased in the mid-1850s by the Rouses from the Sydney cabinetmaker and furniture retailer and importer, Andrew Lenehan. Lenehan also produced designs for furniture from Smee’s catalogue in colonial timbers, which occasionally surface on the auction market.[33] He may have imported the furniture in Rouse Hill House directly from Smee’s in London, or bought it from a large shipment auction at the wharf.[34]

Rouse Hill House & Farm collection, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

With Smee’s success at the Paris 1878 International Exhibition and its inclusion in the Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue for that exhibition, it is not surprising that Smee announced to the public in Sydney in early 1880 that most of the exhibits at the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition were sold out. Their new catalogue, nonetheless, was available from the attendant, who was taking orders.[35] In fierce competition with C & R Light and William Walker & Sons, the company exhibited in Sydney a large collection of dining, drawing room, and bedroom furniture against a backdrop of wallpapers — also for sale — by the prestigious company Jeffries & Co. The Sydney Daily Telegraph noted that the exhibits were ‘exceedingly recherché’.[36] Smee followed the trend in British stores, international exhibitions and the window displays of retail emporiums by exhibiting their furniture in apartments arranged like domestic interiors.[37] Exhibiting the modern ‘early English and other superior Styles’, for which they received first prize, the catalogue boasted that these styles were as ‘now supplied to the higher class Residences in England, but at moderate prices’. A satinwood toilet table was especially commended.[38] Smee’s exhibition furniture was not cheap. AJ Riley selected his entire furniture from Smee for his residence in Macquarie Street opposite the Royal Mint, including his bedroom furniture manufactured to ‘special order’ in the Early English style. Made in birds-eye and American walnut, it was engraved and decorated in gold. The style was ‘exactly similar to suites shown by the Messrs. Smee at our LATE EXHIBITION’, the advertisement puffs, connecting private domestic interiors to public display, commerce and spectacle. Riley wanted 250 guineas for this suite alone.[39]

Updating styles

Although Smee had manufactured ebonised and painted furniture since around the mid-1870s, it is unlikely that they showed any at Sydney’s 1879 exhibition. Maintaining their reputation in the colonies for heavier furniture that attracted the conservative male consumer, they exhibited Early English variants of the modern Gothic revival style, with characteristic detailing of ornamental carving and turning, inlay, gold details and bevelled glass mirrors. But customers could order art furniture from their catalogue at the exhibition. Indeed, it was Farmer & Co. of Victoria House, Sydney, which announced in June 1879 the arrival of ‘ART FURNITURE’ and the popularity of the Early English revival style in furniture, rhetorically crediting AW Pugin, Charles L Eastlake and Bruce J Talbert for the end of ‘what has been in England aptly termed “The mahogany reign of terror”’.[40] Upstaging the David Jones emporium and furniture manufactory, which showed Early English furniture in 1879, Farmer’s manufactured a Queensland kauri pine ebonised and incised ‘Orrinsmith cabinet’ in 1880, styled by its in-house designer R Venn Brown, ‘formerly with Messrs Jackson and Graham, of Oxford-street, London’. Following the English fashion for ebonised art furniture with hand-painted panels, Farmer’s customers had the option of ordering a version with panels painted by a ‘Mr T. Phillips, “National Scholar” and Prizeman, late of the National Art Training School, South Kensington School of Design’ and a resident of Sydney.[41]

Inspired by Mrs Orrinsmith’s illustrated treatise, The Drawing Room (1878), which advocated the moral benefits of artistic decoration for the family and society, Farmer’s cabinet is best seen as responding to the rise in female consumption and the new pressures on women to take an active role in ‘Art in the Home’.[42] The arrangement of an interior becomes less formal and symmetrical during the 1880s, and lighter occasional chairs in Queen Anne and ebonised styles were popular novelties for the drawing rooms of the younger generation. But the paterfamilias still governed the purse. By the late 1880s, for example, the drawing room of Thomas Cadell’s Macquarie Street residence was furnished with a large collection of Queen Anne chairs, occasional ebonised, incised and inlaid chairs, and a stuff over couch upholstered in plush and tapestry, all from Smee. Up for auction, its sale anticipated the departure of his family for Europe. And several years earlier, the large sale of furniture and household goods at the residence of the Reverend Dr Moore White near Burwood, included suites of furniture made to order from Smee, and James Lawson & Sons, Sydney. Smee’s furniture dressed the villas and mansions of merchants, parliamentarians, dentists and reverends. ‘Gentlemen just now engaged in furnishing in first-class style’, trumpeted the advertisement for the sale of Thomas W Warren’s villa Ruahine at Ashfield, were invited to inspect the entire collection of Warren’s ‘elegant and beautifully finished furniture’, all of which was from ‘special designs by Smee’. This included a set of ebonised mahogany drawing room furniture. Smee’s named reputation for an ‘exceptionally good article’, the advertisement reported, had ‘long since passed late a proverb’ (meaning the beauty of Smee’s article was so recognised that it had passed into a proverb).[43]

Smee in Tasmania

Smee’s furniture was popular well beyond Sydney. Advertisements placed in the Launceston Examiner and Hobart Mercury in October 1879 advise that the firm’s representative agent, Francis Bourne, would visit those towns to secure orders and to distribute the latest catalogue, copies of which could be obtained also from his hotel in Sydney.[44] Smee’s direct contact with Tasmania was not new. In 1870 the company regularly announced in the Mercury that the ‘late firm of William Smee & Sons’ was dissolved and letters were liable to be returned if not sent to John Henry Smee & Company, Cabinet and Upholstery Wareroom, Finsbury Pavement or to their old established manufactory at Chiswell St, Finsbury. Further, it advised that the books of the late firm for 50 years past were preserved, so that previous orders could be referred to. The same notices were placed in the Sydney Morning Herald, and the South Australian Register, confirming Smee’s influence on the cabinet-making trade in these cities.[45] This change was no doubt a major impetus for the production of the new catalogue in 1870.

Caroline Simpson Research Library, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

Competing with the locals: Smee in Victoria

Why Smee did not exhibit at the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition is unclear. It continued to advertise in the Sydney press throughout the time of the Melbourne Exhibition, inviting ‘Friends visiting England to inspect their large and varied stock’ in ‘thirty Warerooms replete with every variety of Furniture’. In competition with two other English firms, C & R Light and William Walker, they offered special arrangements for packing and forwarding orders to the colonies, and their new illustrated catalogue of over 700 designs could be sent ‘post free’.[46] With many furniture and furnishing firms along Tottenham Court Road becoming emporiums in London and the well-known Universal Provider William Whiteley in Westbourne Grove expanding into a huge department store, Smee’s productions of illustrated catalogues increased in fierce competition. In Australia, the resurgence of consumer confidence following the depression of the 1890s was reflected in the Edwardian period revival and decoratively hybrid art nouveau furniture collections illustrated in catalogues of emporia such as David Jones, and Beard Watson in Sydney, and Buckley & Nunn in Melbourne.

But in the last decades of the nineteenth century Smee remained a trusted company for elite colonials to consult. When Edward Knox was redecorating from London his Edgecliff mansion Fiona, under the supervision of his son who had already dealt with Smee, Knox senior sought Smee’s advice on how to accommodate the large sideboard he purchased in Venice in his dining room recess.[47] And from 1886, the fashionable cabinet-making and upholstering firm Tuberville, Smith, & Co., ‘The New English Art Furnishers’ was the large stockholder and sole agent in Sydney for WA & S Smee.[48] Exhibiting from 1879 into early 1880 at the Sydney International Exhibition, Smee may have been deterred by the cost of sending new shipments to Melbourne from London. In any case, clients who could afford Smee would have travelled to the Sydney exhibition, or had the catalogue featuring the ‘700 new designs’ mailed.[49]

But there was also the reality of colonial competition in Victoria. Melbourne-based manufactory and importer WH Rocke & Co. had the lion’s share of the cabinet-making and furnishing trades since the late 1860s, administering to the pretensions of the gold generation, the enfranchised squattocracy and the city merchants and professionals. At the Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition in 1875 it exhibited a large drawing room setting of black and gold colonial blackwood furniture, upholstered in rich canary yellow and brilliant blue satin. A black and gold pier glass and a large window frame draped with matching yellow and blue satin, trimmed with silk bullion, cords, tassels, and Swiss lace surmounted by a black and gold cornice completed the setting. This suite was designed and made by the exhibitors.[50] Never before had the concept of the private domestic interior been made so public and it continued as a market strategy in the colony. At Melbourne’s International Exhibition in 1880, Rocke & Co. created large thematic rooms to show their range of bedroom, drawing room, and dining room furniture, some of it in the modern Renaissance revival styles and in the Early English and Aesthetic styles, hand painted by their artist John Mather. Wallach Bros of Elizabeth Street also showed Aesthetic styles manufactured in Melbourne, including ebonised cabinets with painted panels and hanging brackets in their large drawing room apartment.[51] But in competing with the colonial cabinet-makers, Rocke & Co., James McEwan, Thwaites, Alexander W Norton, Lawson Bros and Wallach, and the British firms, Jackson & Graham, Wylie & Lockhead, Shoalbred, Maple, and Gillow in the late 1870s and throughout the 1880s in particular, Smee had maintained a strong presence in Victoria from the late 1850s. Lane and Serle noted that the new rich pastoralist John Moffatt furnished his mansion Hopkins Hill (Chatsworth) in the Western District with furniture and fittings from William Smee & Sons, Finsbury between 1859 and 1860. Acclaimed by the press during the Royal Visit of Queen Victoria’s second son Prince Alfred in 1867, Moffatt’s interiors provided an exemplary comparative assessment between British and colonial taste in house furniture and decoration.[52] But press and literary comparisons plagued colonials throughout the second half of the century. Criticised by visiting journalists and authors according to English standards, and decried by visiting society or governor’s wives, new moneyed colonial taste was, in spite of Australia’s rapid advance, seemingly showy and behind that of ‘Home’. Such prejudice continued to raise colonial anxieties and fuel the desires of the middle classes to be on a par with the conservative ‘ruling’ taste of Great Britain.

Collections of Smee furniture helped to dress their performance. In the early 1860s DJ Royston’s drawing room furniture in elaborately carved walnut at his Kew residence in Melbourne was manufactured by Smee, as were George Robertson’s mahogany sideboard and wardrobe at his home in Fitzroy. At nearby Como, Robert Downing’s drawing room suite, made by Smee, included a couch and six walnut chairs, armchair and lounge, covered with blue satin damask. All the furniture at John Brammell’s residence in Tennyson Street, St Kilda, came from the colonial cabinet-makers Thwaites and from Smee, and the furniture dressing the drawing room, dining room, hall, study and bedrooms of Briscoe Ray’s St Kilda mansion was from Smee.[53] With accolades for Smee’s lavish display at the 1867 Paris Exhibition appearing in the Melbourne press, the colonial middle-class taste for Smee was confirmed: ‘But perhaps the best example of wood inlaying is found in Messrs. Smee’s stall’, reported the Argus correspondent from Paris, ‘where a very beautiful toilette table is shown in satinwood, inlaid with purple wood’.[54]

Rouse Hill House & Farm collection, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

In 1870, Stubbs, Oxley & Co. auctioned an entire private collection of drawing room furniture by Smee in carved walnut wood including a conversational couch, music stand, Albert and Victoria chairs, a large chiffonier and a carved oval centre table. At Argyle villa, St Kilda, the walnut drawing room suite covered in green satin was by Smee, and when Mrs Porter left for Europe in the early 1870s, she sold her entire collection of household furniture from her residence Cleveland, in Flinders Street, Melbourne, all of which had come from Smee, Finsbury, and Lawson Bros, Melbourne. Auctioneers Stubbs & Co. sold a family’s entire collection of Smee’s walnut, papier maché, and carved and gilt drawing room furniture, and mahogany dining room furniture, including a massive richly carved Spanish mahogany sideboard. Dr Pugh’s Collins Street, Melbourne, residence included a massive carved mahogany sideboard by Smee and a large mahogany extension table by Wylie & Lochead. All the drawing room and dining room furniture in Edward Keep’s St Kilda villa was made to order by Smee.[55]

Caroline Simpson Research Library, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

By 1881 Melbourne auctioneers of new imported British furniture would remark that the dining rooms suites in the Early English and mediaeval styles were ‘equal to Smee or Walker’s manufacture’.[56] Mrs William Webster, who was returning to Europe, sold from her mansion Eidura in St Kilda a massive 18-piece mahogany dining suite upholstered in maroon morocco, a 2.1-metre sideboard, 4.6 metre dining table and a matching carved three-tier dinner wagon, all made by Smee. And the entire collection of household furniture was made to order by Smee for Job Smith’s residence Thornbury Park, Northcote, including ‘exquisite bedroom suites in ash’.[57] The large dining room suite at William Kerr Thomson’s mansion, Kamsburgh, Brighton, was from Smee, and it is not surprising that the large collection of Sir George Verdon, connoisseur and Manager of the ES & A (English, Scottish and Australasian) Bank in Melbourne, included occasional chairs and a large box ottoman by Smee, inlaid with thuja and holly wood and enriched with ormolu.[58]

Verdon was the representative Commissioner for the British Court at the 1888 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition, a position that authorised his wealth and status, and his strong cultural and commercial connections to Great Britain. Smee, the only British cabinet making firm to exhibit, was awarded a ‘First Order of Merit’. ‘Their display is one that does them great credit’, enthused the Argus, ‘and is certainly superior to anything of the kind that is to be seen in the building’:

They show a massive dining-room suite in pollard oak, with a sideboard which is a triumph of the cabinetmaker’s art. This design is most artistic, the carvings upon it are delicate and true, and the general workmanship is unexceptionable. They also exhibit two bedroom suites, one of satinwood, and the other of black walnut. Both of these are exceedingly handsome, and have been much admired by visitors. The cabinets are fitted with bevelled plate-glass, and the toilet tables have massive marble slabs, and are inlaid with tiles richly painted.[59]

Smee’s display reflected the taste for the ornate Renaissance revival, which by the end of the decade matched the boom style Italianate architecture of the 1870s and 1880s estate mansions built throughout town and country.

In addition to generating sales and orders for similar furniture, the display at the 1888 exhibition appears to have resulted in a partnership between Smee and fashionable Melbourne cabinet manufacturer, importer and furnishing firm, Cullis Hill & Co.[60] After the exhibition, Cullis Hill’s stock included a large Smee ‘Renaissance style’ dining-room suite in pollard oak, which included a 6-metre table, a sideboard with richly carved panels, a massive dinner wagon and an overmantel. The firm’s owner, Cullis Hill, may have retailed the massive exhibition suite. The sale of his own household furniture from Tudor Lodge, Hawthorn, in 1891 included pieces by Gillow and Smee. The dining room furniture listed in his sale as a ‘Carved Oak High back Suite’ may well be the exhibition suite, but Mark Moss’s residence San Remo in East Melbourne was furnished by Smee, Gillow and Maple, and his pollard oak dining-room suite matches both the description of Smee’s suite at the 1888 Melbourne International Exhibition and that stocked by Cullis Hill.[61]

Conclusion

It is clear from the vast number of auction, sale and exhibition notices this article has mustered (there are many others) that Smee did far more than outfit a small number of houses in Australia, as historians have generally assumed. Smee supplied a large quantity of furniture to the colonial middle and elite classes, and was a major influence on the colonial cabinet-making trade. Forthright advertisers and very much a manufacture of styles, Smee & Sons marketed furniture to middle-class colonials throughout the second half of the nineteenth century.

The questions remain: Where is it? and: Why has so little Smee furniture appeared to have survived in Australia?[62] A recent (2008) auction in Tasmania included an early colonial cedar wing wardrobe from the late 1840s, made by prominent Sydney cabinet-maker Joseph Sly to patterns adapted from Smee’s catalogue and George Smith’s Collection of Designs for Household Furniture (1808). The same sale included an Andrew Lenehan colonial cedar fold-over centre pedestal card table with paw feet, dating to about 1845–50, made from a design by Smee, with a New South Wales provenance.[63] Similarly, a huon pine wardrobe influenced by Smee in the Greek-Revival taste was auctioned in Sydney in 2002 and the contents sale of Dysart House, Tasmania in 2011 included a large, mahogany extension dining-room table, from around 1850, styled and stamped by Smee.

Mossgreen, Melbourne

The layering of the Rouse Family collection of furnishings and furniture over 150 years is exceptional — and unique — in the history of Australian house museum interiors. Indeed, a William Smee & Sons chest of drawers was purchased for one of the Elizabeth Bay flats following the 1941 conversion, and was bought from a tenant in the early 1970s by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales as a link with that history of the house when the Trust worked towards the interpretation of the Macleay family period of the late 1830s and 1840s. And the Trust purchased a large mid-nineteenth century break front wardrobe with a pediment by William Smee & Sons for Vaucluse House in the early 1980s, which was later transferred to Elizabeth Bay House. But the whereabouts today of most Smee furniture brought to this country is elusive. Where, for instance, is the furniture from Smee & Sons that the Hon. J Frazer, MLC, auctioned at his Woollahra mansion, Quiraing, in 1876, or the large quantities of Smee furniture in mahogany, walnut, birch, bird’s eye maple and Hungarian ash shipped regularly from London and sold throughout 1878 in Sydney?[64]

Rouse Hill House & Farm collection, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney

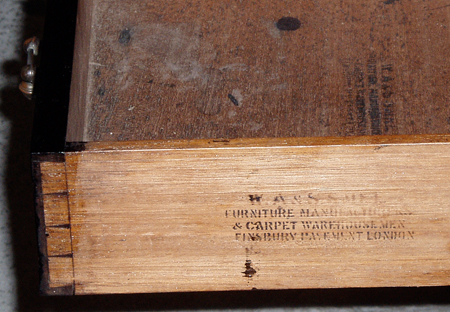

Modern throughout the nineteenth century, despised in the early twentieth century for being Victorian and then valued as antiques from the mid-to-late twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries, Smee furniture was prized by its contemporary owners, and touted by exhibitors and auctioneers as objects of status and cultural capital. However, Smee furniture was not often stamped and surviving pieces that include the manufactory stamp or label are probably vestiges of customised orders.

From the London manufactory in Finsbury to wharves in Australia, from the warehouse to the Australian auction room and from the showrooms and retailers to the country mansion, villa and town house, Smee catered for a range of middle-class markets with its historicist and modern art styling. Manufacturing similar patterns for decades and transforming its ranges to meet the changes in fashion and consumer taste with new marketing and distribution strategies, Smee was a huge enterprise and its styles reflected as much as directed middle-class materialism and aspiration. Much of Smee’s furniture may not have survived along with the nineteenth-century architecture it inhabited, but given the weight of the contemporary record this new research brings forward, some ‘Victorian’ furniture collections appearing in auction rooms around Australia must include, or be styled after, pieces from Smee & Sons, Finsbury.

Notes

Thanks to HHT staff, Matthew Scott and Matthew Stephens, and to Shinae Stowe.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes 1-20

1 James S Virtue, London & New York, 1863, p. 204.

2 The name of the Smee company in Finsbury changes, but it is predominately listed as William Smee & Sons, Smee & Sons from the 1820s, William & Syluns Smee Manufacturers, Smee occasionally during the mid-century and, from the late 1860s, WA & S Smee, William Smee and Son and also John Henry Smee & Company.

3 Brisbane Courier, 30 November 1893, p. 8; The presence of Smee in Western Australia and South Australia is yet to be explored, where in the later colony, especially, the company’s manufactures were likely to be prevalent.

4 The auction notes for an early Victorian satinwood étagère (Lot 196, Sale 5924 at Christie’s, London, 22 September 2009) mention that ‘patterns for related “whatnot” shelves featured in the 1830s catalogue of the Moorfields cabinet-makers Messrs William Smee and Sons’.

5 For the rise in furniture imports from Britain to colonies between 1850 and 1890, see ET Joy, ‘The overseas trade in furniture in the nineteenth century’, Furniture History, vol. 6, 1970, 67; Deborah Cohen, Household Gods: The British and their Possessions, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2006, pp. 39–41; Linda Young observes that in 1840, the Australian market for the importation of British furniture was the second largest after India and outstripped exports to the North American markets: see Young, ‘Extensive, economical and elegant’: The habitus of gentility in early nineteenth century Sydney’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 36, no. 124, October 2004, 201–20 (p. 205).

6 W. A. & S. Smee’s Designs of Furniture, a Stock of Which Is Always Kept Ready for Sale at the Cabinet, Upholstery and Bedding Manufactory and Wareroooms, No. 6. Finsbury Pavement, London [1870], p. 1.

7 Helen C Long, ‘Pattern books and manuals of Victorian exterior and interior details’, in Victorian Houses and their Details, Architectural Press, Oxford, 2002.

8 Charles L Eastlake, Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery, and Other Details, Longmans, Green, London, 1868.

9 For example, Eastlake’s book was reviewed in the South Australian Advertiser, 15 April, 1869, p. 4 and the Launceston Examiner, 4 March 1869, p. 3, and sold in Melbourne through George Robertson bookshop: Argus, 27 September 1869, p. 3.

10 Susan Weber Soros, The Secular Furniture of E. W. Godwin, Yale University Press, Yale, 1999; Elizabeth Aslin, E. W. Godwin, Furniture and Interior Decoration, John Murray, London, 1986, p. 22.

11 ‘Drawing-room furniture/manufactured by R. Hunter. 6 Eden Street, Hampstead, London, N.W./ Maker’s reference number F. G.; 44’, The Cabinet Makers’ Pattern Book. Being Examples of Modern Furniture … from Original Designs … Issued as Supplement with the ‘Furniture Gazette’, London, 1877–79. Information for the identification of this plate was obtained from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

12 Kevin Fahy, Australian Furniture: Pictorial History and Dictionary, Casuarina Press, Woollahra, Sydney, 1998, p. 14;‘W. Smee, 6 Pavement, Finsbury, 13 November 1834’: MS 11936/543/1187290; ‘Messrs Smee and Sons, Little Moorfields, 10 February 1835’: MS 11936/543/1194321, National Archives, UK.

13 Memoir of the Late Alfred Smee F. R. S, by his Daughter, with a Selection of his Miscellaneous Writings by Elizabeth Mary Odling, George Bell & Sons, York Street, Covent Garden, 1878; Maitland Mercury and Hunter River Advertiser, 9 October 1847, p. 3 [Reprinted from Liverpool Albion, 14 June 1847].

14 ‘Metropolitan Railway-Moorgate Terminus/North London Railway-Liverpool Street Terminus/William Smee & Sons, Decorators, Cabinet Makers, Upholsterers and Bedding Warehousemen, respectfully direct attention to the conveniences now afforded by the above Railways, of access to their Warerooms, No. 6 Finsbury Pavement, and No 34 Little Moorfields, which are within respectively one and four hundred yards of the Stations. Residents at the West End of London, and upon the North London, North-Western, Great Northern, Midland, Great Eastern, Great Western, Chatham and Dover, and South Coast lines of Railway generally, can now reach the City within a very short time, and in most cases without change of carriage. William Smee & Sons’ Salesmen wait upon intending purchasers in the above district, and throughout the country to prepare Estimates, and with Designs of Furniture and Samples of Materials free of charge’, British Friend, 1 December 1866, p. 312:

15 ‘Messrs. Bassett and Co.’s new bank, Leighton Buzzard’, Building News, 21 December 1866, www.leighton-linslade.com/tours/other/lb_barclays.html.

16 ‘Inventory and valuation [of the late] Mrs Dulany’s property at 69 Grand Parade by William Smee and Son of 7 Finsbury Pavement [16 October 1828]’: Series No: AMS6025/62, National Archives, UK; the Sydney Morning Herald edition of 26 February 1846 reprinted an article from the Chelmsford Chronicle: ‘The remains of Mrs Elizabeth Fry were interred on Monday, in the Friends’ burying ground at Barking, in this county … About a quarter before eleven o’clock the funeral cortège proceeded en route to Barking, under the superintendence of Mr Smee, of Finsbury Pavement’ (p. 3).

17 British Friend, 1 January 1867, p. 1.

18 Deborah Cohen, ‘Cathedrals to commerce: Shoppers and entrepreneurs’, in Household Gods: The British and their Possessions, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, pp. 32–62.

19 William Smee and Son, Ltd, Designs of Furniture by William Smee and Son, a Stock of Which Is Always Kept Ready for Sale at their Cabinet and Upholstery Manufactory and Warerooms, W Smee, London [184-]. In an effort to compete against the upholsterers’ stronghold and the popularity of the Tottenham Court Road manufacturers in London, Smee also produced an extensive illustrated catalogue, Designs for Window Curtains and Beds, and ran a large business in upholstery, wallpapers and textiles.

20 ‘Decorative Furniture’, in The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue: The Industry of All Nations, 1851, George Virtue, London, 1851, p. 164; The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1862, James S Virtue, London & New York, 1862, pp. 204, 209.

Endnotes 21-40

21 Edward Joy, ‘William Smee and Sons’, Pictorial Dictionary of British 19th Century Furniture Design, The Antique Collectors Club, Suffolk (1977) 1980, p. xxix.

22 Linda Young notes a preference for rosewood — rather than mahogany — furniture in the early decades of the nineteenth century in Sydney in her study, ‘Extensive, economical and elegant: The habitus of gentility in early nineteenth century Sydney’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 36, no. 124, 2004, 201–20; Smee’s range of timbers and designs answered the need for novelty as the century progressed.

23 Robert Kerr, The Gentleman’s House: Or, How to Plan English residences, from Parsonages to the Palace with Tables of Accommodation and Cost, and a Series of Selected Plans, John Murray, London, 1864.

24 For a recent study of materialism, medievalism and chivalry in the Victorian colonial context related to commerce and illuminated addresses in Sydney in particular, see Valda Rigg, ‘Medievalism and the colonial imperative: illuminating their links in colonial New South Wales, reCollections, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 2: http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_4_2/papers/medievalism/.

25 RE Twopeny, ‘Furniture’, in Town Life in Australia (London, 1883), Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1973, p. 39.

26 Joan Kerr, &James Broadbent, Gothick Taste in the Colony of New South Wales, The David Ell Press, Sydney, 1980, pp. 96–8. Loudon’s book was first published in 1833 and was reissued periodically throughout the first half of the century.

27 Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1853, p. 8.

28 Sydney Morning Herald, 12 September 1853, p. 1; 9 Oct 1854, p. 6.

29 Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 1856, p7; 15 January 1858, p. 7.

30 Sydney Morning Herald, 6 January 1858, p. 7; 27 February 1860, p. 3; 6 March 1860, p. 7; see also Empire, 28 January 1858, p. 8; January 26 1856, p. 6, for some further auction sale notices.

31 Sydney Morning Herald, 28 February 1860, p. 8; 26 April 1860, p. 8; 20 July 1860, p. 7; 6 September 1866, p. 7.

32 Kevin Fahy & Andrew Simpson, Australian Furniture: Pictorial History and Dictionary, 1788–1938, Casuarina Press, Woollahra, NSW, 1998; Clifford Graig, Kevin Fahy & E Graeme Robertson, Early Colonial Furniture in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, Georgian House, Melbourne (1972), 1980. In line with library catalogue entries and Edward Joy’s Pictorial Dictionary, which date Smee’s pattern book to about 1850, an earlier publication date appeared to be revised, but it still remains likely that a first edition was published in the late 1830s. Fahy’s pioneering research from the late 1960S and early 1970s established the influence of Smee on the designs of early Australian cedar wardrobes, sofas, occasional tables and bookcases, furniture, some in the Greek-Revival taste of the early-Victorian period.

33 Robert Griffith, ‘English pattern books and Australian furniture design’, in Michael Bogle (ed.), Designing Australia: Reading in the History of Design, Pluto Press, Annandale, 2002, p. 35; ‘A Rose Wood or mahogany Tea Poy French polished with cut glass sugar Basins’, William Smee & Sons’ Designs of Furniture [1850], p. 207.

34 For context around these purchases, see Caroline Rouse Thornton, ‘Golden years’, in Rouse Hill House and the Rouses, Nedlands, Western Australia, 1988, pp. 98–105.

35 The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the Paris 1878 Exhibition, James Virtue, London & New York, 1878, p. 187; Sydney Morning Herald, 16 March 1880, p. 2.

36 Sydney Daily Telegraph, 8 October 1879, p. 3.

37 Clive Edwards, Turning Houses into Homes, Ashgate Publishing, London, 2005, pp. 110–12.

38 Official Catalogue of the British Section, Sydney International Exhibition, 1879, JM Johnson & Sons, Holborn, London, p. 103; Sydney Daily Telegraph, 8 October 1879, p. 3; Official Record of the Sydney International Exhibition, 1879, Thomas Richards, Government Printer, Sydney, 1881, p. 221.

39 Sydney Morning Herald, 27 April 1881, p. 10.

40 Sydney Morning Herald, 5 June 1879, p.8: ‘Some of our constituents are familiar with the altered taste in the matter of household furniture at present obtaining in Great Britain, and known as the “Early English Revival”… The antiquarian zeal that possessed many architects at its inception, and often displayed itself in the archaic forms and uncouth decorations of their design, has been corrected by study, a freer treatment of the Gothic style obtains, and the result is domestic furniture of good design in entire harmony with art’.

Endnotes 41-64

41 Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 1880, p. 1.

42 Mrs Orrinsmith, The Drawing Room: its Decorations and Furniture, Macmillan and Co., London, 1878. This text included pictures of furniture and interiors formerly illustrating Clarence Cook’s articles in Scribner’s Monthly, and reprinted in his House Beautiful (1878); A Mrs T Phillips and Mr AD Riley, both former students of the South Kensington School of Design, exhibited art decorations, which showed their system of teaching at the art classes of the Sydney Technical College: Sydney Morning Herald, 2 April 1882, p. 7.

43 Sydney Morning Herald, 27 November 1884, p. 14; 24 May 1888, p.12; 12 November 1890, p. 4.

44 Launceston Examiner, 25 October 1879, p. 1; Mercury, 18 October 1879, p. 1.

45 Mercury, 10 August 1870, p. 4; Sydney Morning Herald, 23 May 1870, p. 6; South Australian Register, 15 February 1870, p. 2.

46 Sydney Morning Herald, 29 September 1880, p. 11; C. & R. Light’s Registered Design Book of Furniture (1880) was available in Sydney from as early as 1881 (see Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1881, p. 3).

47 Terence Lane & Jessie Serle, Australians at Home: A Documentary History of Australian Domestic Interiors from 1788–1914, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Oxford, 1990, pp. 31–32.

48 Tuberville, Smith, & Co. were also later the stockists for William Walker & Sons, & Liberty & Co., London. See Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May 1886, p. 12; Art Society of New South Wales Annual Exhibition Catalogue, 1888, n. p.; The firm become Tuberville, Smith, Norton & Co. until its dissolution in 1890, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 September 1888, p. 6.

49 As the depression eased, William Walker joined forces with cabinet-making and furnishing firm in Sydney, Bartholomew & Sons, becoming Wm Walker, Sons & Bartholomew Ltd, located in Bunhill House, named after the London manufactory in Bunhill Row, London, next to David Jones in George St, Sydney: see invoice and graphic, National Gallery of Australia: NGA 88.1983; Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 1896, p. 4.

50 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1878 (Melbourne, 1875), Offical Record containing Introduction, Catalogues ..., McCarron, Bird & Co., Melbourne, 1875, p. 135.

51 Argus Exhibition Supplement, 11 October 1880, p. 22.

52 Lane & Serle, Australians at Home, pp. 125–6.

53 Argus, 9 August 1864, p. 2; 20 October 1865, p. 2; 17 March, 1866, p. 2; October 1866, p. 2;15 January 1867, p. 2.

54 ‘Paris Exhibition’, Argus., 11 October 1867, p. 7.

55 ibid.; Argus,18 June 1868, p. 2; April 6, 1870. p. 3; 6 February 1871, p. 2; 15 August 1871, p. 2; 7 March 1872, p. 2; 24 November 1873, p. 3.

56 Argus., 15 August 1881, p. 2.

57 Argus., 7 February 1885, p.3; 6 February 1886, p. 3.

58 Argus., 10 December 1888, p. 2 ;1 June 1892, p.2.

59 Argus., 11 December 1888, p. 9; Argus Exhibition Supplement, 15 Jan 1889, p. 94

60 Providing a decorating service in competition with Rocke, Cullis Hill & Co. fitted out many mansions, including Landcox, North Brighton, for which it selected Chippendale, Early English and Anglo-Japanese furniture from Gillow and Walker & Son.

61 Table Talk, 12 December 1890, p.3; Argus, 5 September 1884, p.2; 13 April 1891, p. 2; 22 October 1892, p. 2.

62 Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales: Accession nos: EB86/36-1:4; EB86/35.

63 Fine Colonial Art, Furniture and Decorative Arts at Somercotes, Ross, Tasmania, Mossgreen Auctions, Hobart, December 2008.

64 Sydney Morning Herald, 2 March 1876, p. 9; 30 May 1878, p. 3; 12 September 1878, p. 10; 12 December 1878, p. 3.