Banned

The National Archives of Australia has over the past decade mounted a succession of engaging and innovative exhibitions, many starting their life as displays in its Canberra office, in the former East Block on Queen Victoria Terrace. The most recent offering, Banned, is based on the Archives’ huge collection of publications built up through enforcement of the Customs Act of 1901, the instrument that maintained Australia’s long-standing inviolability from books, magazines, films and recordings deemed to be unsuitable. The exhibition incorporates archival documents and actual books, along with a web-based supplement. Guided, or inspired, by Nicole Moore’s recent book, The Censor’s Library (University of Queensland Press, 2012), the exhibition is relatively modest compared with the 2010 University of Melbourne exhibition Banned Books in Australia. Nevertheless, it might prompt researchers and visitors to reflect upon the relative freedom we enjoy to write and read what we choose: a freedom still enjoyed by a minority of the world’s population.

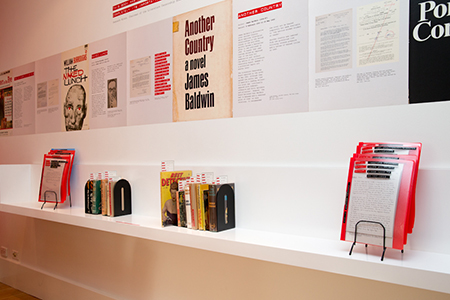

For about five decades in the mid-twentieth century Australia’s censorship regime patrolled its intellectual borders rigorously – arguably far more rigidly than in comparable societies, including (according to the exhibition text) ‘England, Europe and America’. Banned, ingeniously and economically mounted in the Archives cafe, gives a vivid, entertaining and insightful picture of the kinds of decisions Australian customs officials made about thousands of imported publications between the 1920s and the 1970s.

photograph by Angus Kendon, National Archives of Australia

Australia became notorious for its official disinclination to countenance ‘certain publications which have no literary or cultural value’: though the Customs department responsible had no way of deciding what standards it should enforce. While these works included political tracts uncongenial to governments (regulations prohibiting ‘seditious publications’ were promulgated in 1921) the focus of censorship was, as a a customs minister declared in 1938, those that ‘cater to those seeking to satisfy depraved tastes’. Sometimes the political and moral categories overlapped. John Harcourt’s communist novel Upsurge became the first novel to be banned by the Commonwealth Book Censorship Board. Initially banned as ‘seditious’, a review confirmed the ban on the grounds of indecency.

Indeed, customs officers overwhelmingly policed imported publications on moral grounds. As the exhibition’s text panels make clear, ‘literary and scholarly works’ comprised only a small percentage of the works policed or prohibited. Regulations introduced in 1938 focused on pulp novels, salacious magazines and outright pornography as threats to Australian morals and indeed to its literary standards. The exhibition depicts the invariably lurid covers of works such as ‘pulp’ detective novels by Mickey Spillane, ‘True Confession’ magazines and ‘bodice-rippers’ like Kathleen Winsor’s Forever Amber (banned from 1945 to 1958) as well as serious literary works, such as James Baldwin’s Another Country (banned from 1963 to 1966).

photograph by Angus Kendon, National Archives of Australia

While thoughtful officials, such as Sir Robert Garran (Solicitor-General from 1916 to 1932), acknowledged that ‘the boundary line between what is indecent and what is not is very difficult to draw’, the customs officers who enforced the regulations saw few dilemmas in imposing their personal morality. They enforced regulations without public disclosure, test or censure, and only when authors, publishers or readers objected was the regime challenged. Customs ministers would overrule the advice of the Literature Censorship Board established in the 1930s, and only in the 1950s, following persistent lobbying from publishers, authors’ bodies and civil libertarians, did the restrictions ease.

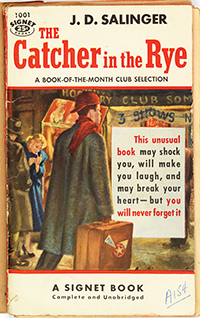

Banned focuses on serious literature, highlighting cases representing turning points in the administration of book censorship. The treatment of JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye demonstrates how public challenges to censorship hastened its end. Though sold in Australia since 1951, it was banned in 1956 after a customs clerk found it offensive. Customs officers seized a copy from the Parliamentary Library in September 1957, even though the US ambassador has presented copies as representative of his nation’s modern literature. The act prompted the Sydney Morning Herald to object that ‘this country has one of the most arbitrary – and perhaps one of the most inefficient – systems of book censorship in the world’. Its editorial condemned Commonwealth censorship as capricious and superfluous and called for its end.

Signet Books, 1953

National Archives of Australia, C3059

Banned deals less with magazines and other media than it does with books. It includes just one example each of the censorship of a television program and a gramophone record, though the first example, an episode of the British television comedy series The Goodies, offers a particularly fine example of the complexities of censorship. In 1974 Australian censors directed that the ABC ‘allow initial shot of Goodie looking up girl’s dress’ but cut ‘all shots of naked girls under the showers’. In today’s atmosphere of moral concern over the sexual abuse of children, we might speculate what public taste rather than official direction would countenance today.

The National Archives has imaginatively devised a range of means to explore the subject. They use the cafe’s tables as murals of the covers of books, display facsimiles of Archives files documenting the archives collection, and invite visitors to read for themselves copies of a dozen or so of the books featured in the exhibition. The Archives has long been a leader in digital technology and hosts a blog (www.blog.naa.gov.au/banned) inviting comments and questions and directing those interested to further sources. While this openness is in keeping with the exhibition’s celebration of liberalism, it includes a invitation from Archives staff to ‘access this dataset …’ – raising the question of whether it is worse to ban English prose than to mangle it.

photograph by Angus Kendon, National Archives of Australia

Banned implicitly advocates freedom of expression. However, it is less an exploration of the merits of freedom of expression than a reminder of the absurdity and folly of seeking to regulate or ban literary or cultural expression. The exhibition focuses largely upon literary works that challenged the boundaries of taste, rather than the pulp fiction and pornography that exercised the great majority of customs officers’ determinations. Whether an exhibition, in a cafe or elsewhere, could do justice to the complex ethical and ideological dilemmas of censorship is another question.

Peter Stanley is co-editor of reCollections: A Journal of Museums and Collections, and has recently taken up a research professorship at the University of New South Wales in Canberra.

| Exhibition: | Banned |

| Institution: | National Archives of Australia, Canberra |

| Curator: | Tracey Clarke |

| Exhibition and graphic design: | Lora Miloloza (NAA) |

| Venue/dates: |

ongoing |

| Floor space: | Display located in cafe, approx. 40 square metres |

| Website: | http://blog.naa.gov.au/banned/ |