review by Peter Londey

At an academic conference associated with the exhibition, Alexander the Great: 2000 Years of Treasures, something close to a fight broke out, in the final panel session of the day, over the issue of how we should think about Alexander. Prominent ancient historian Robin Lane Fox had argued that Alexander’s post-colonial, post-imperial detractors had been unduly influenced by the examples of Stalin and other modern despots. But, argued a notable academic in the audience, Alexander was himself an autocrat and a mass-murderer, a destroyer rather than a creator.

The exhibition organisers, in particular Anna Trofimova, the head of the Department of Classical Antiquities at the Hermitage, tried to calm things down, pointing out that the 4th century BC was a different time, and that we cannot judge Alexander by the standards of our own age. Quite right too: it is never the historian’s task to cast moral judgements on the past (though many forget this). Yet the spat was interesting, because it cast into relief the question of why the State Hermitage Museum of St Petersburg, which had provided the exhibition, and why the Australian Museum in Sydney, which is staging it, chose to centre it on the figure of Alexander at all.

photograph by C Bento, © Australian Museum

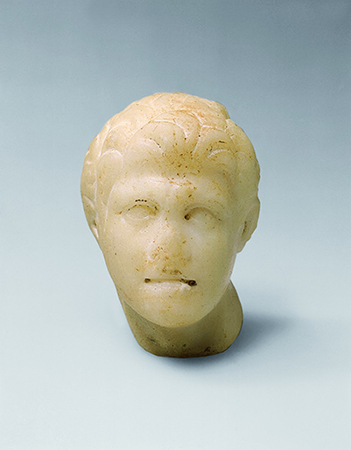

The truth is that this is not an exhibition about Alexander the Great, much as it tries to market itself as one. There is not a single item in the exhibition which Alexander owned, or is even likely to have set eyes on. (A partial exception is that there are Roman copies of statues which Alexander might have seen on his travels.) The only ancient portrait of Alexander, other than coins and cameos, is a 6-centimetre-high Roman marble head from Asia Minor, a copy of a 2nd century BC Greek original.

© 2012 The State Hermitage, St Petersburg

Only in the final section, on the reception of the Alexander myth in later ages, does the image of Alexander loom large. For the rest, this is a sort of life-and-times exhibition, with cultural material presented from Greece itself (rather little from Makedonia) and from the varied cultures with which the Greeks and Alexander came in contact. Given that Alexander marched his army from Makedonia to India, that provides a broad canvas. But it leaves a fundamental disconnect between the story of Alexander, which runs through text on the walls and talking heads on AV screens, and the contents of the showcases.

So why pretend that the exhibition is about Alexander? Presumably the main answer is to do with the marketing of blockbuster exhibitions. In an associated performance in the museum, aimed at young children, there is a certain amount of ahistorical nonsense, such as Alexander fighting Dareios in single combat (don’t worry, nobody suffers more than a sprained ankle), but also a piece of historical reality. By putting on Alexander’s helmet (which in reality, of course, has not survived, and thus is not on display) the central character acquires the use of Alexander’s army to defeat the evil mayor who wants to close the museum to build a carpark. So the great Alexander saves the museum.

Now this is sad. I would have thought that any historian alive today was told on his or her mother’s knee that the Great Man view of history was dead and buried, yet with the public, and in museums which need to lure large numbers of the public through the doors, this is apparently not so. The idea of the unique individual who single-handedly changed the world remains one of our dominant cultural myths, however much historians may try to complicate the simplistic stories which result.

But does it matter, if the museum has succeeded in luring thousands of visitors into an exhibition displaying a remarkable array of cultural material, at the expense of a little false advertising? Well yes, I would say it does, because it has left the real story of the material being displayed to be interpreted only through individual item captions (which, in the general way of things, few visitors will read). For the material on display is remarkable, and worth appreciating on its own terms. The Hermitage does not have a collection of Alexander material worth exhibiting, apart from the reception material collected by the Tsars. But it does evidently have a superb collection of material from various parts of the old Russian empire, and a decent smattering of material from further afield, such as Egypt and India.

With this material we could have had a fascinating exhibition on the subject of cultural contact and influence, and the challenges of interpreting the archaeological evidence that results. The exhibition includes material from peoples around the Black Sea, who were in contact with Greek colonising ventures for several centuries before Alexander. Some items are purely local, such as a 5th century BC Skythian coat of chain mail, or a set of 4th-century Thrakian bridle decorations. But others from Skythia and from the Greek but culturally mixed Bosporan kingdom of the Crimea (which provided Athens with much of its grain in the 4th century) display a real fusion of Greek and non-Greek themes and techniques. There is a story to tell with these items (mainly arms and armour, and jewellery), but they are scattered through the exhibition.

© 2012 The State Hermitage, St Petersburg

Other items are more purely Greek in style, and taken together give a vivid picture of the cultural life of the Greek cultural outposts around the Black Sea. Here are the makings of a truly astounding exhibition. But Alexander wanders off, following the king himself through Asia Minor and the Levant to a more or less random collection of Egyptian material ranging from the 4th century BC to the 8th century AD. Striking among these are a range of mainly 4th century AD Coptic textiles; but the connection with Alexander is rather frayed. Similarly a group of Palmyran sculptures from the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD seem to have no point except to show off the range of the Hermitage’s collections.

Elsewhere there are truly remarkable objects, but you have to hunt for them. One, for example, is a horse breastplate made of wool, felt, fur and gold leaf, depicting a procession of lions, possibly from 3rd century BC Iran but found in a burial mound in the Pazyryk valley near Novosibirsk. Scattered through the exhibition are other Iranian items found in Siberia, alongside local Siberian items made by groups such as the Sacae. There is also a small but interesting collection of material from the area of the 3rd to 1st century BC Greek kingdom of Baktria in Afghanistan: some items pure Greek, others made by local peoples but exhibiting Greek influence. To summarise, there are cultural riches here. But you have to seek them out, and you have to read individual item captions attentively to see their significance.

Where Alexander and Alexander finally meet up is in a fascinating section on reception, discussing the king’s strange and imaginative afterlife in the Alexander Romance, and his frequent appearance in a range of later societies’ artistic traditions. This section is well supported by text panels and by informative essays in the sumptuous catalogue. Suddenly Alexander is at the centre of things, but really this is almost a separate exhibition.

© Australian Museum

I have been critical, but there is also much that is good here. Objects are well displayed and captions, if you read them, are informative. In crowded areas I would have liked a duplicate set of captions along the top of showcases, to save elbowing people out of the way to read captions beneath the objects.

As an atheist, I was offended by the claim that the exhibition used the direly politically correct ‘BCE’ and ‘CE’ because ‘BC’ and ‘AD’ are ‘exclusively Christian’. Not to me, they aren’t. But elsewhere this exhibition escaped the shackles of political correctness in a refreshing way. One panel pointed out that the Makedonia of Philip, Alexander’s father, encompassed parts of modern Greece, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Makedonia (that much correctness did survive), Bulgaria and Turkey, cutting across modern nations’ attempts at exclusivity.

In sum, go to this exhibition if you have a chance: not for Alexander, but for the broad collection of cultural material and connections on display. And why has such a rich collection been relegated to a sort of background wallpaper for the life of one man? In Australia, one suspects, marketing. In Russia, perhaps the same. Or perhaps just as Alexander, the supposed archetype of the successful but also good ruler, appealed to the kings of France and the Tsars of Russia, so today in Putin’s Russia he finds resonance.

Peter Londey lectures in ancient Greek history at the Australian National University; in a previous career, at the Australian War Memorial, he was historical curator for a number of exhibitions.

| Exhibition: | Alexander the Great: 2000 Years of Treasures |

| Institution: | State Hermitage, St Petersburg, Russia |

| Venue: | Australian Museum, Sydney |

| Curator: | Dr Anna Trofimova, Head, Department of Classical Antiquities, State Hermitage, St Petersburg, Russia |

| Exhibition design: | Aaron Maestri |

| Graphic design: | Lucy Dougall |

| Catalogue: | Alexander the Great: 2000 Years of Treasures, Australian Museum, Sydney, 2012, A$29.95 |

| Venue/dates: |

Australian Museum, Sydney |