Pegging out the camp

Finding broader histories in camping gear

If collections of camping equipment held in Australian museums often appear thin and purely opportunistic it is largely because there has been no history of camping with which to constitute camping as a distinct field. Camping gear tends to be framed by reference to other activities — bushwalking, mining, military, surveying, etc. — but not as illuminating camping itself. In this article I look at some instances of how material culture can shape such a history and how a focused history can lend much deeper meaning to familiar items of gear. Working together they can generate a fresh approach to the story of settlement in which the practices and technology of camping move from the margins to the foreground. While it has certainly evolved, camping equipment (and, therefore, camping practices) also reveals a remarkable longevity. This reflects the role of camping as being more than a technology of temporary habitation and points to its continuing part in a process of cultural and social formation.

From 1788, tents continuously dotted the Australian landscape: sometimes standing alone, sometimes part of vast encampments. For a century and a half, a camp was a sign of the leading edge of settlement: of geographical frontiers, of new capitals, of frontiers of industry, frontiers of knowledge, and frontiers of recreation. First settlers, squatters, surveyors, overlanders, land selectors, industrial campers of many sorts, soldiers, the unemployed, utopians, field naturalists, ornithologists, bushwalkers, organised youth campers, holiday campers — and many more — all camped. It was necessary but it was more than a necessity, for camping out was a learning experience: how to live in the Australian environment and how to live as an Australian. It was the default mode of habitation: the local people always camped and when Europeans arrived they, too, had to camp. This generated a culture that gave material form to the way Australians saw themselves and how they were seen by others: as a nation of campers.

When the Reverend John Dunmore Lang first visited the Hunter River district in 1827 he travelled with a young settler who instructed the camping novice in the correct way to make tea. When the billy was boiling he threw in a handful of tea and some sugar and stirred it with a twig, which he said ‘was called a spoon in the Australian dialect’.[1] If a twig was a spoon, a couple of sheets of bark could make a tent.

Camping techniques and materials crossed the frontier in both directions. As Henry Reynolds and Paul Memmott have shown, Aboriginal people applied Western materials to their traditional domiciliary structures: pieces of canvas, roofing iron, milled timber augmented bark, boughs and grass.[2] Traditional camping practices can be discerned beneath Western materials and configurations. And Europeans adopted Aboriginal camping technology, especially the use of bark.

The white man’s gunyah

photograph by NJ Caire

State Library of Victoria

The term ‘gunyah’ was first recorded in 1803. It is a Port Jackson Dharuk word for a lean-to bark shelter.[3] As the word was carried by settlers away from the Sydney area it came to denote any native dwelling. Gunyah and words such as ‘mia-mia’ (variously ‘mi-mi’ and ‘mimi’) and wurley (variously ‘wurlie’, ‘wirlie’) were commonly used by Europeans to denote a native dwelling and generally do not seem to have differentiated types.

Early settlers could see that stringybark was a useful material, but they had to learn from local people how to harvest it and heat it to make it flat so that it could be used for building. The learning process appears to have taken decades. Architectural historian Miles Lewis has found no record of any independent European bark construction in Australia before 1815. The familiar bark hut with its roof of sheets of bark tied down with lengths of sapling did not appear until about 1840. Lewis warns against making too large a claim for Aboriginal influence on settler building technologies, but he does allow that ‘bark construction is one of the few forms which might seriously be thought to have derived from the Aborigines’.[4] With respect to temporary shelters, there is considerable evidence to support this view.

A bark lean-to was widely used by Europeans in situations where a temporary shelter was needed but a tent or tarpaulin was either unavailable or too heavy to carry. Usually made of one or two sheets of bark resting with one end on the ground and the other against a cross-piece supported by two forked sticks (as in Caire’s Camp), it remained a practical alternative to a tent until the beginning of the twentieth century. While some gunyahs are direct copies of Aboriginal structures, others are simply improvised shelters made of found natural materials. Yet whenever the name ‘gunyah’ is attached to such a structure, it implicitly acknowledges an association with Aboriginal ways.

Over time, the practical advantages of a bark shelter overcame the initial prejudice against them as being too uncivilised. Hunting was one activity to give rise to this expedient reappraisal. In 1818, while on a hunting and fishing excursion up the Warragamba River, physician and landowner Sir John Jamison and two friends slept in a gunyah of myrtle-branches.[5] One of the ‘views’ by former convict Joseph Lycett in his widely circulated 1824 Views of Australia shows a group of hunters enjoying a campfire while one of their number rests in a gunyah nearby. The image indicates a positive attitude towards using a native shelter.

The image on the title page of the first volume of Thomas Mitchell’s Three Expeditions, published in 1839, shows how much attitudes to native dwellings changed over the 40 years since Hunter decorated his Journal with a condescending image of a native brush shelter. Mitchell represents himself lying comfortably on the ground in precisely the type of Aboriginal habitation the members of the First Fleet found beneath their dignity to enter. It was not a mere pose, for Mitchell had a genuine appreciation of native camping.

On one occasion, being caught in rain and having passed two very substantial gunyahs earlier he ‘wished to return, if possible, to pass the night there, for I began to learn that such huts, with a good fire before them, made very comfortable quarters in bad weather’.[6] Pastoralist Edward Curr agreed. In 1886 he pronounced: ‘Having camped out a good deal in the bush, I do not hesitate to pronounce the bark hut of the Blacks the most comfortable shelter I have met with, where firewood is obtainable, and much preferable to a tent.’[7]

Angus McMillan took no tent on his 1839 exploratory trip from the Maneroo district to what would become known as Gippsland. For 16 months he put up gunyahs ‘like the Aborigines’.[8] In the late 1830s Alexander Mollison lived in grass mia-mias while he built up a sheep station.[9] When Henry Meyrick arrived on his run at Boniang, in Victoria, in 1840, he slept ‘under a myah-myah which the Aboriginal guides knocked up’.[10] In the 1860s, James Stevenson, a pioneer in North Queensland, built a good-sized tea-tree bark shelter along the Burdekin River.[11]

Here we formed our camp, and as we intended staying for some time, we built a gumyah, after the manner of the coast blacks. We cut about a dozen long saplings, and piled them somewhat in the style soldiers pile their rifles in a camp. This left a good sized space inside. Then stripping of a quantity of tea-tree bark, we thatched it all round, with the exception of one space which we left for a door. This completed our sleeping compartment, and very comfortable and dry we found it.[12]

While this ‘gumyah’ bears no resemblance to what is called a ‘gunyah’ elsewhere, there is no doubt that it was a settler’s version of a native dwelling. Further evidence of direct copying is provided in an 1868 handbook which offered advice to emigrants intending to go on the land:

Temporary house accommodation is always easily provided by means of a few sheets of bark stripped from the neighbouring trees, one extremity resting on the ground, the other resting in a slanting direction on a pole a few feet above the ground, fixed on two forked sticks, in the shape of the roof of a house. This erection is called a gungah — the native style of house architecture, and the first approach that is made to house-building.[13]

Reg Murray was a member of the Victorian Geological Survey. In 1873, when investigating the gullies in the Tarwin area the forest was so dense it was not even possible to take in a packhorse. He and his brother-in-law, Henry Ford, had to walk in. Carrying a heavy tent or tarpaulin was not feasible.

In camping at evening we would make a mia-mia in a few minutes with a couple of forked saplings about 5 feet high and a ridge pole six or seven feet long, with sticks leaning against it and fern tree fronds as a thatch and backing. Fern fronds, bracken and other suitable stuff were used to cover the ground inside, and on these we laid our oilskin swags-wrappers to keep out the damp, and spread our blankets on top. A big fire was made in front of the mia-mia, so that no matter how wet we may have got during the day we could unpack our swags in shelter and warmth, put on dry things, sleep dry and dry our clothes for next day. The fern fronds thatch kept off rain very well, though later we added to our stock a small light calico fly about 3 or 4 lb. in weight, which, spread out over the mia-mia, made an effective shelter or could be used alone in dry weather.[14]

Numerous observers, including travel writers William Howitt, Edward Snell and G Butler Earp, and artist Eugene von Guerard, all report seeing gunyahs and mimis on the goldfields, occupied by white miners. Hybrid structures of canvas and bark were commonly called ‘tents’ while others referred to their tent as their ‘gunyah’. This extension of the vernacular suggests a popular understanding that living in a tent was, in some sense, living like Aboriginal people. Incorporating the white man’s gunyah in museum collections, perhaps alongside the black man’s tent, would show how camping blurs cultural difference at a most primal level: that of habitation.

The gunyah was kept alive as a recreational camping shelter well after it had been abandoned by settlers and miners. The 1885 Victorian Railways Tourist’s Guide offered four pages of advice including how to camp without a tent by making a bed of ‘bush feathers’ under a bower or ‘a la blackfellow’ with a bark windbreak. In 1911 the cover of Donald Macdonald’s Bush Boy’s Book showed a gunyah with a fire in front. It was a model for white boys to copy. Directed towards encouraging individual competence rather than organised group camping of the Boy Scouts type, it Australianised camping by associating it with an Aboriginal tradition.

Tent as first home

Museum Victoria

The image of young land selector Edna Lethlean living in a tent on a Mallee block in 1921 could be taken as endorsing a popular narrative of ‘pioneer hardship’ (an ancestral sacrifice for which modern Australians are forever expressing gratitude, as if hardship were the single, defining, experience of pioneer life). But Edna’s energy speaks of someone defined not by hardship but by determination, possibly even idealism. (The costume could almost be that of a 1970s rural hippie living on a commune.) The bell tent tells us this is an ex-army tent valued for its heavy-duty canvas, and the solid bush carpentry of a capacity to improvise from minimal resources. The image forces us to reconsider a popular view of pioneering: hardship was a test, not a permanent condition; there was also pleasure from living like this — the pleasure of making do and getting by. Modern campers still connect to that.

Tents appeared each time land was opened up or new colonies were started. The first free settlers who came to the Swan River, Adelaide and Port Phillip all camped. A tent was first home, often for months, sometimes for years. In November 1836 Mary Thomas and her family arrived at Glenelg with the first hundred emigrants to settle in South Australia. At first they put up a small tent in the sand dunes and slept around the fire but soon they moved to a better spot and a larger tent. A month after arriving, Mary wrote that despite the mosquitoes and fleas and the dingoes prowling around she was enjoying ‘the freedom of the open air and our spacious tent’.[15]

The local Aboriginal people came around, shaking hands and inspecting the tents. Amused at Mary’s unsuccessful attempt to cook over an open fire, something she had never done, they pulled away all the sticks and rebuilt it so that it burned well. Her 15-year old son, William, later improvised an oven from iron hoops and clay in which his mother baked bread, pies and puddings. Another improvisation was to insulate the tent against the heat by tacking up an inner tent made of some green curtains they had brought with them. (The ‘fly’ — an outer canvas roof — seems not to have come into wide use until later in the nineteenth century.) The Thomases camped at Glenelg for nine months before moving to a town acre in Adelaide in June 1837.

The collective memory of this long transitional moment has been marginalised in favour of narratives shaped by what Grace Karskens calls an emphasis on ‘heavy’ structures.[16] Yet these recurring periods of ephemerality are not merely a preamble to settlement proper, but are its actual beginnings. To ignore this is to leave gaps in Australian history at crucial formative moments. It is in this extended period of camping that settlers first attach themselves (literally, with ropes and pegs) to the Australian earth and make it, for them, a place of meaning. Tents, tarpaulins, bush furniture, kerosene tins and camp ovens, combined with texts and images, can help us re-imagine those elusive periods and incorporate them into broader histories of settlement.

As Edward Kynaston writes, camping is a very different experience from householding.

Houses are static defences against nature and the elements. Tents and fabric shelters are really a form of extra clothing, but a form inside which you can move about. They are not houses nor substitutes for houses. This is an important distinction which is often, and too easily, forgotten. Houses are a rejection of nature, tents and fabric shelters are the apparel you wear at various times outdoors to enable you to live continuously and acceptingly with nature.[17]

But the line between camping and homesteading was also blurred; camps often became semi-permanent; tents were given slab walls and stone, mud or tin chimneys. Bark was laid over the canvas, entombing the tent, which became the interior walls and ceiling. Yet even as domestic life was progressively interiorised, cooking often continued to be done outside or under a bough shelter.

Camping required a suite of new skills and, most importantly, a capacity for improvisation. This produced many items never found in a tentmaker’s catalogue. On their first trip to their selection in Gippsland at Jumbunna East in 1883, the Rainbow brothers stayed overnight in the tent of another selector. They noted how the furniture was made from hazel sticks and sheets of bark. When they reached their own selection they applied what they had learned. They made beds with four forked sticks driven into the ground on which bags were stretched across a frame of hazel. For the kitchen tent they made a table from another four stakes braced and topped with split blue gum slabs. On each side of the table, two forked sticks were driven into the ground and a sapling laid between them; that was the seating. The candlestick was another length of sapling with three nails driven into the top to hold the candle.[18]

Camping for gold

Improvised dwellings could be objects of considerable pride. James Armour’s party sewed up a tent from blankets, bed linen, some towels and a tartan plaid and stretched it over a ridge pole supported by forked sticks. ‘Though not so grand looking as many of the neighbouring edifices, it was our own, and the occupiers of those others might not be able to say more’.[22]

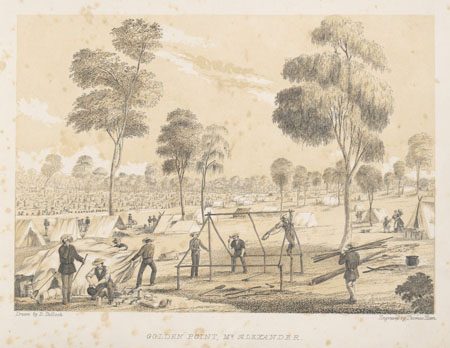

engraved by Thomas Ham

Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

Ham shows the erection of a tent on a sapling frame. The size of the structure and number of men involved suggests it was for a party of six, at least. It is pitched near a cluster of tents, all well away from the busy creek and there is no mining in the immediate vicinity.[23] This was typical as the camping areas tended to surround the workings rather than to be among them. Some took trouble to find as pleasant a spot as they could. Many chose the hills, preferring a quiet spot even if it meant walking further to their claim. They did what campers do.

From the moment they landed in Victoria, gold seekers camped: they camped in the canvas suburbs that surrounded Melbourne, they camped as they travelled to the diggings, and they camped when they got there. By 1858 about 180,000 people, or a third of the population, were living under canvas or in improvised structures.[24]

The novel experience of camping was a major theme in the writings of journalists and travel writers who visited the goldfields. William Howitt purchased a tent in London before coming to Australia. Like most newcomers, he had never camped out. When on the way to the diggings heavy rain caused water to come through the seams and soak the travellers’ belongings, Howitt declared to the world that ‘Messrs Richardson of the New Road will find it necessary to dress their seams with some waterproof preparation, or sew them tighter, to maintain their credit as tent-makers’.[25] Nothing, he says, was more important to the travellers’ health and comfort than being able to camp well.

Henrietta Walker lived in tents for seven years with her husband and young child. She remembered her first Sunday on the diggings with great affection:

Of course there was no table, and no one thought of chairs. They covered an upturned bucket with a coat for me to sit on; and though there was only one fork, and the men had to use their sheath-knives, we were all as happy as we could be. They were great days.[26]

Tentkeeping was an essential domestic function, and was usually undertaken by men. Members of a party rotated the responsibility and sometimes the occupants of three or four tents ate together, rostering a different person each week to take a turn as cook and housekeeper.[27] In her study of the California gold rush, Susan Lee Johnson examines the gender reversal on the fields there as men took on the tasks of cooking, washing, mending and housekeeping. Despite the intuitive expectation that the miners would privilege the work of finding gold over domestic tasks, she found that ‘gold seekers paid great heed to their more immediate desires — for shelter, for food, for company, for pleasure, for some way to make sense of what was a most novel situation’. Johnson argues that ‘foregrounding domestic or reproductive labor in a history of a mining area, where mining labor might be assumed to take precedence, is itself a gesture toward unsettling that hierarchical relation’.[28] There is no reason to think this less true of Australia than of California.

Campfire politics

It was around the campfire, not the mineshaft, that the conversations took place that grew the armed rebellion at Eureka. In the unusually open society of the campgrounds, shared complaints were shaped into radical proposals around campfires even before they were discussed at mass meetings. These small group discussions drew cohorts together and the outdoors and peripatetic life allowed easy exchange with neighbours, the finding of common ground, and the rapid amplification of demands.

The insistent egalitarianism that developed was possibly less a result of the spreading of radical ideas or Leveller sympathies (although these helped shape resentments) and more a product of the way in which people lived and worked. Mutual obligation was reinforced through partnership agreements and a non-ideological form of self-management was quickly and widely established as the prevailing social ethos. In a situation where, on a daily basis, personal and communal self-reliance largely substituted for government order, and government itself was identified as physically and socially separate as well as malign, a culture of activism inevitably arose. The campgrounds became temporary demonstrations of a social model that was more egalitarian, self-managing and free than was colonial society in general.

The physical, social and legal marginality of the campgrounds, the extreme nomadism of the diggers and, most of all, the profound belief of the actors in their ability to manage themselves, were seen by the 1854–55 Goldfields Commission of Enquiry as primary factors contributing to the origins, continuity and scale of the political unrest.[29] Miners had come into contact not just with ideas that seriously challenged the autocratic basis of colonial government, but also with a daily practice that made it possible to largely ignore it and even to defy it. Camping was the domestic and social basis on which the goldfields were constructed, and which served as the medium for political unrest.

Holiday campers

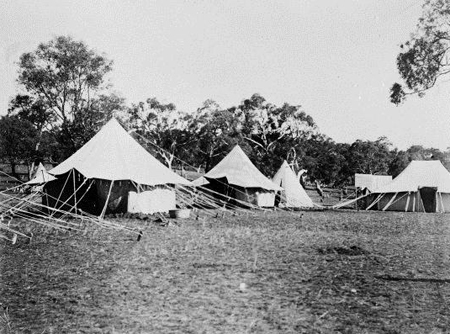

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Summer holiday camping was well established at Sandgate, near Brisbane, when this snap of the Williams family was taken in 1905. As early as 1896 tents stretched for well over a kilometre and campers commonly stayed until after the New Year. In the same period there are reports of ‘hundreds of campers’ at nearby Wellington Point.[30] The campground there, and those at Humpybong and Redcliffe, were serviced by steamers carrying up to 600 passengers. It was at this time that the term ‘campers’ — replacing the cumbersome ‘campers-out’ — first came into widespread use.

The expansion of the rail network and coastal steamer routes, the widespread use of the safety bicycle, together with horsedrawn vehicles, enabled people to get to campgrounds in very large numbers long before the motor car became a common mode of transport. By the end of the nineteenth century, the time was available, transport was available and the tent was available.[31] Holiday camping became a new communal event, with temporary communities formed of social groups as well as families.

In Australia (as in other settler societies such as the North America and New Zealand, but not in Britain or Europe) holiday camping was largely a matter of adapting an older practice to a new purpose. Many early beach holiday set-ups used the sapling-framed tent of settlers and bush workers. The means were the same but the meaning had changed.

The large holiday campground soon generated a culture of its own, but many holiday campgrounds had other histories. Some would be among the oldest sites of settlement, reaching back in a continuum to pioneers and to early contact with local Aboriginal people. Their status was often preserved by being located on crown land. We can discern the range of these sites from the 1949 road guide Highways of Australia produced under the editorship of Charles Barrett.[32] Of the 140 touring camping places he details, 42 are on riverbanks, especially near bridges; 33 are foreshores; 31 are public reserves such as municipal parks and showgrounds; and the remainder are on private property and roadsides. Most of the managed campgrounds are maintained by local authorities and Barrett lists only 11 commercial campgrounds. The camping spots with the deepest histories would generally be the riverbanks, but roadsides and showgrounds had long serviced rural industries.

Until the 1930s, bicycles, trains, steamers and horsedrawn vehicles remained the main forms of holiday transport. A horsedrawn van could carry all that was needed for an entire party, but early model cars were not suited to the purpose and trailers were often necessary. From a camping point of view, the car was simply another means of transporting the tent and gear, but the tent began to be freshly marketed as an accessory to this new means of transportation.

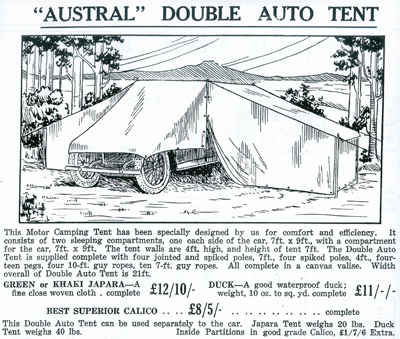

Museum Victoria

In 1927 tentmaker Evan Evans began offering new products ‘in view of the great deal of camping and touring now being done since the advent of the motor car’.[33] The most singular new offering was a range of tents that had space for the car as well. While the 1941–42 catalogue of the camping retailer Hudson’s Stores advertised several models of auto tents it also included bell tents and wall tents virtually unchanged since the mid-nineteenth century.

The Australian camping holiday has its roots deep in a distinct settler history and it carries strong resonances of the colonial past. Campers ritually partake in a tradition embodied in return to a place of meaning but not of ownership, by physically making a camp, and by conducting themselves according to handed-down camping lore. With items of camping equipment such as tents, stretchers, folding furniture, sleeping bags and so on, we can see links to the old past in objects, images and practices from the recent past.

The national camp

National Library of Australia

Following the passage of a bill establishing the Australian capital in December 1908, early in 1909 a party of parliamentarians tested Canberra’s suitability as a national capital by camping there for a few days. Later the same year the surveyors came in and set up their camp. After Walter Burley Griffin won the competition to design what was to be the most modern capital city in the world, he and his wife Marion Mahoney Griffin camped on the spot, carrying water up from the river and playing euchre in their tent in the evenings. As the site for the new parliament building itself, Griffin chose an undulation known as Camp Hill. The public was invited to witness the opening of the new parliament house but, as Canberra had only one hotel, campgrounds had to be set up for an expected 15,000 people. It seems that most of those who witnessed the ceremony were campers, just as campers had witnessed the raising of the British flag at Sydney Cove in 1788.

The first Europeans camped on the Molonglo without permit or licence in the 1820s[34] and a century later locals could still point out the clump of gum trees where the pioneer drover James Ainslie camped.[35] When construction of the capital buildings began in 1913, hundreds of workers were brought in and housed in tents hidden away in the hills.[36] Walking among their old campsites, Canberra historian Anne Gugler can point to evidence of saplings being cut down for tent poles and firewood, and lines of rocks and remnant domestic plants indicating where gardens were made around tents and humpies. The tracks that ran around the camps are still there. Such traces draw the great camp of parliament into a narrative of Aboriginal camps, squatters’ camps, surveyors’ camps, workers’ camps, camps for the unemployed and even tourist campgrounds.

By the end of 1929, the old camp was needed for the growing numbers of local unemployed, as well as for men passing through in search of work. The last labourers’ tents were removed in 1931 but unauthorised camps continued to appear. By 1939 the national capital had become a tourist attraction and a camping park on the river offered views of the government buildings ‘glimpsed in a perfect setting across the stream’. A map of the time suggests that this tourist campground may have been on the site of the National Museum of Australia.

The supreme irony was that the new parliament building was itself regarded as a temporary structure, officially called the ‘Provisional’ Parliament House, sited at Camp Hill. Its 70-year provisionality was perhaps an unintentional acknowledgment that the nation itself remained in a condition of being unfinished, of remaining suspended ‘in between’ arrival and permanence.

The national capital’s largely ignored canvas history was dramatically engaged in January 1972, when an umbrella sprouted in front of Parliament House to protest Aboriginal land rights. The umbrella was soon replaced by a tent and by April there were eight tents. The camp became known as the ‘Tent Embassy’. As the camp attracted national and international attention, the protestors realised they had stumbled on something with extraordinary symbolic impact — not an embassy, but a tent.

National Archives of Australia

The question of what the camp symbolised came to occupy protestors, detractors and commentators alike. To some it represented traditional Aboriginal life and to others the degraded town and station camps. To many it was a site of struggle, expressing solidarity with the Gurindji who in 1966 had walked off Wave Hill station in the Northern Territory and were still camped out in protest at Wattie Creek. To some politicians it was an ‘eyesore’, while to others it was a protected site of democratic activity.

Architectural historian Gregory Cowan describes the Tent Embassy as an invasion of Canberra parodying the claims of British sovereignty by reversing the situation at Sydney Cove, where ephemeral English tents confronted established Aboriginal order.[37] The Tent Embassy is an unsettling of European order, asserting an older right to camp in that place. It is difficult for settler Australians to deny the power of a ragged camp to represent a legitimate claim to sovereignty without denying their own colonial origins. When camp faces parliament across the lawns, which ‘temporary’ structure has the deeper roots, the greater historical meaning?

Even the holiday associations of the tents contribute to the subversive effect.[38] The Tent Embassy allows an extraordinary range of meanings to be laminated onto it because they are already present in a history recovered by imaginative association. It shows, more succinctly than any other evidence, that Australian history is one in which camps are, despite their ephemerality, not marginal but part of a central discourse. The Tent Embassy reveals the symbolic power of a camp in the context of the particularities of Australia’s history. It captures in one ambiguous, flimsy form a great sweep of the past from before 1788 to the present, bringing to the surface a depth of cultural meaning that resonates, even if divisively, with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Present and future collections

A frying pan may be the most telling item in the collection of camping equipment held by the National Museum. It belonged to Norm Kopievsky, who in the 1950s lived at the Jindabyne Dam construction camp, part of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. The familiar cooking implement directs our attention away from the labour towards the domestic life of the hundreds of thousands of industrial campers who built Australia’s infrastructure and serviced rural industries from the 1850s to the 1950s. It reminds us that camps, not houses, were very often the primary domestic setting of workers, and that men did their own cooking, washing and sewing. Instead of being a site of insistent masculinity, the bush camp is also a site of male womanliness.

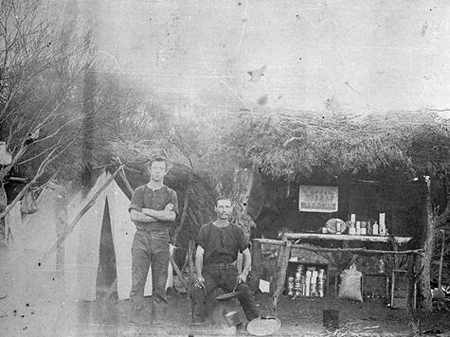

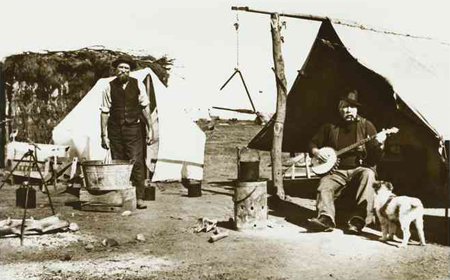

It is remarkable how often men in work camps chose to be photographed with a frying pan in hand. The image of two land clearing contractors at their camp is rich in details of construction, materials, bush carpentry and so on, but what is most striking about this scene is the pose of the young men against their neatly arranged (and well-stocked) bough shelter larder. They are proud of their domestic arrangement, assertively denying any contradiction between being a working man and a capable homemaker. It is not the image of masculinity we usually associate with the bush.

Museum Victoria

From the mid-nineteenth century, large work camps spread around the continent to enable the construction of the road, rail, dam, communications and other projects needed by a growing and more distributed population. This industrial scale camping physically joined the colonies. There were also thousands of small bush camps that serviced the pastoral and farming industries or enabled continuing maintenance of infrastructure. Across the four eastern colonies in the 1880s there are estimated to have been as many as 56,000 shearers on the move for up to four months annually.[39] This wandering workforce was at other times engaged in fencing, carpentry, dam-building, navvying, harvesting, ringbarking, rabbiting, kangaroo-shooting and other short-term jobs that depended on camping out. Yet, while there is a common awareness that bush workers camped, indeed are often celebrated as the quintessential bush campers, camping is nearly always thought of, and therefore presented as, ancillary to the work and not as a practice with its own history and culture.

Writing about the transcontinental railway, built between 1912 and 1917, Patsy Adam-Smith says of the thousands of workers employed constructing it: ‘Within a few months of their having left, the tent houses and hessian camps that had been their homes for four years, had gone. Nothing remains as a memorial to their work but the 1.052-mile steel rail they laid’.[40] This is no longer true, as railway history has proved popular with museums. Collections and oral histories held at the Queensland Museum, at Launceston, and elsewhere, acknowledge the part the camps played. The Snowy Mountains Scheme is also recognised as camp-dependent, but this is usually imagined as huts rather than as the tents with which it began and on which the surveyor in charge, former Army surveyor, Major Clews, insisted. He had the strong view that if any of his men did not like living under canvas they shouldn’t be there at all.[41]

If the material culture of camping in all its applications — knowledge-gathering, industrial, military, recreational, etc. — suggests that camping has played a significant part in the cultural evolution as well as in the physical and economic making of modern Australia, including crossing the cultural divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous technologies, why has it been overlooked? Patsy Adam-Smith suggests it may be the very ephemerality of camps —they literally disappear — that explains their historical invisibility. The curious thing is that we know the process of white settlement depended on camping. Is it, as Grace Karskens suggests, that our identification of heritage with heavy structures, with permanency, has caused a certain myopia? Is it an ingrained tendency to think of true foundations as being solid — of stone or brick, not canvas?

Another problem is pinning down a definition of ‘camping’. Dictionary definitions struggle. Camping has such broad connotations that we are driven back to something as simple as ‘staying at a place for a while.’ Material culture helps us peg it down, but a history of tents or camping equipment would not in itself be a history of camping. Camping is a social practice imbued with passed-down lore. This understanding is still to be integrated into both historical and museum thinking.

The vast bulk of camping-related material held in Australian collecting institutions is in the form of images, mainly photographs. These are already a major driver of the historical research and a pointer to the sort of physical items we might expect to find in museum collections. A greater focus on the material culture would prompt more historical work. Many images are very difficult to accurately date precisely, because camping equipment changes so little over such extended periods, and so little is known about the technology. The work is yet to be done that will allow us to accurately identify the range of historical tents and gear and the periods of their use. At present it is less the camping gear itself and more other evidence such as clothing and mode of transport that helps date images. The problem is complicated by the fact that camping equipment is remarkably durable, and campers have a well-known tendency to hang on to old gear.

State Library of South Australia

The common classification ‘work camp’ often begs the question as to what we are looking at. In this photograph of workers camped while building the Trans-Australian Railway, the huge line-building project itself is invisible: this is a picture of how the men live more than how they work. Their ease in the presence of the camera is explained by the fact that the photographer, John Henry York, was one of their own. It is full of detail. The varieties of quart pots and the triangle hanging from the tent ridgepole that could be for calling people for meals suggest they might be cooks, but they are not at work cooking. As the banjo and the dog tell us, work camp life was not all work. Without its accurate dating, this could be an image of a workers’ camp from any period from the 1850s to the 1930s.

The difficulty of dating camping images without provenance confirms the remarkable continuity of the material culture. Ambiguity and uncertainty is itself evidence. In constructing long-form histories such as that of camping, identifying differences does not trump discerning continuities: the emergence of new technologies may not be the most important part of the story.

Although most museums hold some items of camping equipment, significant material has not yet been acquired. This is especially (and surprisingly) true of tents. Although tents are not essential for camping we might expect them to form an important part of even a basic collection of camping equipment. Yet very few tents seem to be held by Australian institutions and those that are represent a narrow selection when considered against the breadth of the field.

The National Museum of Australia holds three tents, associated with the bushwalkers Myles Dunphy, Hazel Merlo and Dot Butler. As biographical items they tell us of the intimate relationship of these individuals to their small hiking tents and, using Melissa Harper’s The Ways of the Bushwalker,[42] they can be linked to other histories of conservation, national parks, wilderness, and environmental awareness. But they represent a very small (if intense) expression of an intimacy widely experienced by those who have used tents.

A family holiday tent is also a powerful site of intimacy and memory. Family camping is very well represented in the photographic record, yet no Australian museum appears to hold a family holiday tent. Holiday camping is important not only in itself but also as a portal to the broader histories of camping, by linking the familiar present to the unfamiliar past. The National Museum does have a popular example of a 1950s caravan — as do the Powerhouse and Museum Victoria — but I suspect these are valued more for their design rather than for a connection to camping, which, in any case, is problematic. Most campers would deny that caravanning is camping.

Among what seems to be a surprisingly small collection of tents at the Australian War Memorial (most of those catalogued are of the one-man type: hoochies, ponchos and so on), there is one that stands out — a standard British military bell tent dating from 1914–17. It is of the sort used by the AIF and, while it was acquired for its military associations, the tent refuses to allow itself to be pinned down to that context alone. Inside one of the flaps are inscribed places and dates that refer to its use by the Salvation Army Girls Youth Group between 1925 and 1940. It was purchased by the Salvation Army in 1919. This recycling provokes reflections on the military origins and associations of other organised youth camping movements such as Scouts and Guides, and their place in the histories of recreational and educational camping. That camps have been favoured as sites of moral training is further evidence of the capacity of camping to shape and sustain national as well as sectional values.

Tents acquired from army disposals have been widely used for civilian purposes and the bell tent can be seen in images of beach campgrounds even prior to the First World War. It is this multi-purpose, recyclable character of camping equipment that allows us to draw disparate histories together to reveal the interweaving processes of cultural formation as popular practices migrate from one form of camping to another. The relationship between military camping and civilian camping is long and complicated and in the Australian context it is an open question which has influenced the other more.

With notable exceptions, non-Indigenous campsites have not yet been extensively examined by archaeologists. The exceptions include the 1629 shipwreck camps on the Abrolhos Islands, Daisy Bates’s camp at Ooldea, the site of the 1829–30 tented settlement of Peel Town at Clarence in Western Australia, and the Dolly’s Creek goldfields settlement in central Victoria. Susan Lawrence’s book on Dolly’s Creek shows how history and archaeology can work together to shape a much fuller narrative than either discipline can alone.[43] The artefacts found at Dolly’s Creek are mainly those from improved tents with bark walls and stone or brick chimneys, but they do relate to habitations that began as tents and continued to have canvas or calico roofs.[44] They speak of the length (not the brevity) of the transitional period of ephemeral settlement, as newcomers slowly built their way into the landscape.

If we compare the range of potential camping artefacts with what has been collected, large gaps become apparent, even in easily collectible areas such as holiday camping, camping by selectors, industrial camping and, starkly, the Tent Embassy (where is that umbrella?) Instead, there appears to be an overreliance on the photographic record. The small collections of artefacts tend to favour items such as folding camp furniture and ironware. When the absence of tents is raised with curators, it is commonly assumed that old tents and tarpaulins have simply rotted away. While this is probably true in most cases, it is also the case that campers and farmers have traditionally kept old tarps and tents, either as mementos or to be recycled for other purposes. Campers are deeply nostalgic and are loathe to throw out favourite equipment. In interviews with some 50 campers in 2001, most could point to some piece of ‘old gear’ they had assimilated into their current set up.[45] Canvas is remarkably long lasting when not exposed, and tents from the nineteenth century almost certainly still exist, if not intact. The sheds, garages and under-the-houses of Australia are where old camping gear will be found.

Iron tent pegs (or ‘pins’ as they were called in 1788) are certainly findable. Few have found a place in collections. (The Museum has one, a tent peg used by the archaeologist John Mulvaney as a digging tool). Some of the missing ones are famous, such as the ‘Leichhardt’ peg, found in 1891 in the possession of an Aborigine in the Great Western Desert in 1891 and possibly associated with the 1846 expedition on which the exploring party disappeared. But where is it now?[46] A tent peg picked up at Daisy Bates’ campsite also seems to have been mislaid, or simply thrown away. The casual disappearance of such items suggests they have been undervalued. Yet the tent peg is the instrument with which Europeans first staked themselves to the Australian earth: properly contextualised, tent pegs could be as culturally symbolic now as they were essential once. Exploring the symbolism of tents and camps in drawings, paintings and photographs is another way of bringing camping gear into play as part of Australian cultural history.

Tentmakers catalogues, such as those held by Museum Victoria, are the tip of the iceberg of the history of the manufacture, sale and popularity of tents. Company histories should be researched. Vernacular camping techniques are another rich field: especially the use of sapling frames, which were often left intact for later campers to throw their tent over. Bush furniture is already a familiar collectible, but its connection to camping is often obscured. It exemplifies the culture of making do and improvisation that not only characterised settler life but also became incorporated in notions of national character.

Our remarkable colonial dependence on tents is already mentioned in Godfrey Rhodes’ 1858 Tents and Tent Life from the Earliest Ages to the Present Time. His book reminds us that the skills of making temporary habitations are among the most ancient and common to human cultures and Australian camping techniques are part of a long transnational genealogy. Not only is there a crossover between Aboriginal and European camping techniques, as seen with the gunyah, but the extensive study of Aboriginal camping could serve as a template for the study of settler camping: types of structures, layout of camps, etiquette, law and lore, cooking, gender negotiations, aesthetic considerations and so on. We need an ethnography of white camping. Traditional Aboriginal camps were governed by law but so was settler camping. There is an extensive official literature of rules and regulations that charts the spread of the bureaucratic management of camping and, more significant culturally, there is also unwritten white camping lore that is yet to be gathered. A more inquisitive collecting of camping equipment would even reveal linkages between colonial camping in the nineteenth century and modern holiday camping, for remnant expressions of ‘old’ Australian ways stubbornly persist in today’s campgrounds.

While a history of camping in Australia provides a rationale for extending and narrativising museum collections, more material evidence will drive and confirm the historical work. Researching camping offers a fresh and grounded approach to the still mysterious processes of civic and cultural formation during the many periods of ephemeral settlement. Historically informed collections of camping equipment would encourage us to think of camping as much more than a useful solution to a practical problem.

Endnotes

1 Alan EJ Andrews, Major Mitchell’s Map 1834: The Saga of the Survey of the Nineteen Counties, Blubber Head Press, Hobart, 1992, p. 34.

2 Henry Reynolds, With the White People: The Crucial Role of Aborigines in the Exploration and Development of Australia, Penguin Books Australia, Ringwood, 1990; Henry Reynolds, The Other Side of the Frontier: An Interpretation of the Aboriginal Response to the Invasion and Settlement of Australia, History Department, James Cook University, Townsville, 1981. Paul Memmott, Gunyah Goondie & Wurley, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2007.

3 Paul Memmott, Gunyah, Goondie & Wurley, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2007; Australian National Dictionary Centre, ‘Borrowings from Australian Aboriginal languages’, http://andc.anu.edu.au/australian-words/vocabulary/borrowings-from-australian-aboriginal-languages,. Aboriginal peoples in different parts of Australia had different words for similar shelters, and a number of these words were adopted into Australian English.

4 Miles Lewis, Australian Building: A Cultural Investigation, www.mileslewis.net/australian-building/; Paul Oliver (ed.), Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, p. 1070.

5 Andrews, Major Mitchell’s Map, p. 212.

6 TL Mitchell, Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia; with Descriptions of the Recently Explored Region of Australia Felix and of the Present Colony of New South Wales, facsimile edition, vol. 1 Eagle Press, Victoria, [1839] 1996, p. 247.

7 John Archer, Building a Nation: A History of the Australian House, Collins, Sydney, 1987, p. 22.

8 Don Watson, Caledonia Australis: Scottish Highlanders on the Frontier of Australia, Random House Australia, Sydney, 1984, p. 147.

9 Charles and Elsa Chauvel, Walkabout, WH Allen, London, 1959, p. 17.

10 FJ Meyrick, Life in the Bush (1840–1847): A Memoir of Henry Howard Meyrick, Thomas Nelson and Sons, London, 1939, p. 115.

11 The white paperbark melaleuca leucadendra was also known as tea-tree or ti-tree.

12 James B Stevenson, Seven Years in the Australian Bush, Wm. Potter, 1880, p. 89.

13 Australia in 1866 or Facts and Features, Sketches and Incidents of Australia and Australian Life by a Clergyman Thirteen Years Resident in the Interior of New South Wales, 2nd edn, Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, London,1868, p. 119.

14 TJ Coverdale (ed.), The Land of the Lyre Bird: A Story of Early Settlement in the Great Forest of South Gippsland,The Korumburra & District Historical Society, Korumburra, 1998, p. 183

15 Evan Kyffyn Thomas (ed.), The Diary and Letters of Mary Thomas: Being a Record of the Early Days of South Australia, 2nd edn, WK Thomas & Co., Adelaide, 1915, 49–57 and passim.

16 Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, p. 55.

17 Edward Kynaston, Book of the Bush, Reed Books, Balgowlah, 1990, p. 33.

18 Coverdale, Land of the Lyre Bird, p. 320.

19 Edward Snell, The Life and Adventures of Edward Snell: The Illustrated Diary of an Artist, Engineer and Adventurer in the Australian Colonies 1849 to 1859 (ed. by Tom Griffiths with assistance from Alan Platt), Angus & Robertson, Sydney, and the Library Council of Victoria, 1988, p. 277.

20 William Howitt, Land, Labour and Gold: Or, Two Years in Victoria with Visits to Sydney and Van Diemen’s Land, vol. 1, Sydney University Press, Sydney, [1855], 1972, p. 167.

21 Letter from Henry Burchett, 2 July 1852, Burchett Family Letters, Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria.

22 James Armour, The Diggings, the Bush, and Melbourne: Or Reminiscences of Three Years’ Wanderings in Victoria, GD Mackellar, Glasgow, 1864, p. 15.

23 The dig at Dolly’s Creek found the sites of the tents were on the hillsides. Susan Lawrence, Dolly’s Creek: An Archaeology of a Victorian Goldfields Community, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p.105.

24 Wray Vamplew (ed.), Australians: A Historical Library: Historical Statistics, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, Sydney, 1987, p. 347. The 1861 census defined tents as any building with a canvas roof.

25 Howitt, Land, Labor, and Gold, p. 91.

26 The Castlemaine Association of Pioneers, Records of the Castlemaine Pioneers, Rigby, Adelaide, n.d., p. 215.

27 Anon., Chips by an Old Chum; or, Australia in the Fifties, Cassell and Company, London, 1852, p. 83.

28 Susan Lee Johnson, Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush, WW Norton, New York, 2000, pp. 102–3.

29 Report of the Commission appointed to Enquire into the Condition of the Gold Fields of Victoria, 1854–5, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1855, section xxxi.

30 Brisbane Courier, 28 December 1896.

31 As shown by Richard White, in On Holidays: A History of Getting Away in Australia, Pluto Press, Melbourne, 2005.

32 Charles Barrett, Highways of Australia, Motor Manual Monthly, Sydney, 1949.

33 Evan Evans & Co. Catalogue 1930–31, Trade literature collection, , Museum Victoria, MV TL 16243.

34 Kenneth Binns (ed.), Handbook for Canberra, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra, 1939, pp. 11–13.

35 John Gale, Canberra: History of and Legends Relating to the Federal Capital Territory of the Commonwealth of Australia, AM Fallick & Sons, Queanbeyan, 1927, p. 12.

36 Ann Gugler, ‘The builders of Canberra: Where they lived, 1913–1959’, IFHAA Perspectives on Australian History, Canberra,2000.

37 Gregory Cowan, ‘Collapsing Australian architecture: The Tent Embassy’, Journal of Australian Studies, no. 67, 2001, 30–6 (p. 35).

38 Cowan, ‘Collapsing Australian architecture’ (p. 36); Scott Robinson, ‘The Aboriginal embassy: An account of the protests of 1972’, Aboriginal History, vol. 18, no. 1, 1994, 49–63 (p. 53).

39 John Merritt, The Making of the AWU, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986, p. 43.

40 Patsy Adam-Smith, The Desert Railway, Rigby, Adelaide, 1974, p. 90.

41 Mona Ravenscroft, Men of the Snowy River, Rigby, Adelaide, 1962, p. 23.

42 Melissa Harper, The Ways of the Bushwalker: On Foot in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007.

43 Susan Lawrence, Dolly’s Creek: An Archaeology of a Victorian Goldfields Community, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000.

44 The artefacts are held by Heritage Victoria at the Conservation and Research Facility.

45 Interviews conducted with Sue Gore as part of research for a documentary film project, funded by the Australian Film Commission.

46 According to Darrell Lewis, the peg was sent to magistrate and Leichhardt expert JA Panton in the late 1890s but has not been reported since; email to author, 9 March 2012.