No broken relationship here! The Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb

Zagreb is a city rich in museums and galleries. Signs near the main square point to museums of Croatian history, natural history, arts and crafts, ethnography and archaeology, as well as numerous art galleries and the Zagreb City Museum – all to be expected in a national capital. Less predictably, there are the Museum of Mushrooms and the Museum of Broken Relationships. When I visited the city in mid-2015, I was drawn to the latter, wondering if it related in some way to the perennial tragedy of Balkan politics.

photograph by Stephen Foster

Far from it. The content of the museum is intensely personal and, at the same time, universal in reach. Conceived a decade ago by a Croatian couple whose own relationship had come apart, it is based on the simple premise that ‘societies acknowledge marriages, funerals, and even graduation farewells, but deny us any formal recognition of the demise of a relationship, despite its strong emotional effect’. The founders decided that such break-ups could often be symbolised in a single object: in their own case, a wind-up toy encapsulated their ‘past elation’ and ‘present regrets’. Others contributed their own objects, and the stories that went with them, sufficient to put together an exhibition in a shipping container at the 2006 Zagreb Salon art show. The idea caught on, the objects and stories multiplied, and the exhibition began to tour the world – to Ljubljana, Berlin, San Francisco, Cape Town, Manila, Taipei … By 2015 it had visited 28 cities in 18 countries, the collection had grown to some 2400 objects and the theme of break-ups between couples was extended to include other forms of emotional severance, such as parents from their children.

In 2010 the collection acquired a permanent home on the ground floor of a baroque former mansion in Zagreb, comprising several rooms with walls, ceilings and plinths painted white, so that nothing detracts from the objects and stories. Those on display comprise a small percentage of the overall collection, and have evidently been selected for their visual and thematic diversity, and to represent the range of donors, including gender, age, sexuality and country of origin. The rooms have loose themes: ‘The chips are down. The game is up.’; ‘Private battles, global wars’; ‘In and out of wedlock’, and so on. But curatorial intervention is minimal, and the exhibits – that is, the individual objects and stories – are left to speak for themselves. Potential donors are told that their objects can take any shape or form, and that their captions can be ‘frank, withdrawn, imaginative, witty or sad’, and of any length up to a few pages. Most are short – a can of ‘love incense’ is accompanied by two words: ‘Doesn’t work’. Contributors remain anonymous; their words are translated, where necessary, into English and Croatian, but left unedited, except to exclude offensive or discriminatory material.

photograph by Stephen Foster

Some donors tell poignant, often painful stories of separation, rejection and unrequited love. Some are bitter and resentful, even after the passage of many years. But the prevailing tone is philosophical, perhaps sardonic. There is a lot of wry humour here, in the choice of objects, the stories, and the way they are expressed. The objects defy categorisation: stuffed toys, a dildo, a hockey puck, a ‘divorce day’ garden gnome from Ljubljana, a wireless router from San Francisco (‘We tried. Incompatible’), a magnifying glass from Manila (he made her feel small), and various items of clothing.

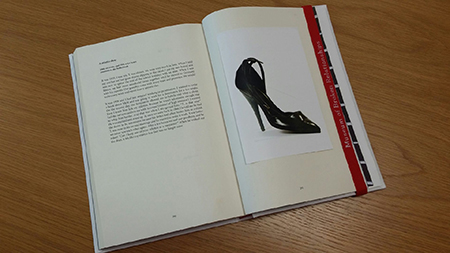

A stiletto shoe from Amsterdam represents a story of childhood romance, three decades of separation, and a surprise reunion: ‘It was 1998 and I had just stopped working in prostitution. I wanted to write a book about S&M and was going to work for a dominatrix for a few weeks.’ As she was whipping a client into submission on her second day, she realised that it was her childhood sweetheart. ‘He told me he had the desire to be submissive because his father had often beaten him as a child.

‘After a few hours we said our goodbyes, and he asked: “Can I keep one of your stilettos as a memento?” When he walked out the door, it felt like my stiletto-less foot was no longer mine.’ The other shoe is on display.

photograph courtesy Museum of Broken Relationships, Zagreb

The curators frankly speculate in an opening panel on why so many people are ready to donate their objects and expose their personal stories to public view: sheer exhibitionism or therapeutic relief? Likewise we might wonder at the museum’s undoubted appeal – if the number of visitors when I was there, and their apparent depth of interest, are in any way typical, the project is a resounding success. Perhaps the appeal simply reflects our fascination with the emotional lives of people like us, especially in areas that people often keep to themselves. Perhaps the museum exposes us as voyeurs. I suspect, though, that its success owes much to the evocative power of objects and to simple, unmediated storytelling, without recourse to cultural studies jargon or contrived sentimentality.

The wry humour of the exhibits finds its way into the museum shop, which sells, among other things, fractured fridge magnets, ‘bad memories erasers’ and T-shirts with attitude. An elegant book, Museum of Broken Relationships: A Diary (Zagreb, 2014), comprises a series of essays that expand on the story of the museum and presents 104 items from the collection. A well-designed website, https://brokenships.com/en, displays a selection of exhibits, and issues an invitation to donors: ‘Wish to unburden the emotional load by erasing everything that reminds you of that painful experience? Don’t do it – one day you will be sorry.’

1966, six weeks, and 1998, a few hours

Amsterdam, the Netherlands

from A Diary, Museum of Broken Relationships, 2014, pp. 290-91

According to an explanatory touch screen, the museum’s donors range in age from 19 to 85 years. Mexico City has responded to the request for donors with the greatest number – 2500 – of online submissions. Australia and New Zealand scarcely figure in the exhibition or the Diary (though a stuffed shark from Canberra and a couple of stories mentioning Australian partners prove that this part of the world is not immune to broken relationships). Perhaps these countries will only be properly represented when the exhibition travels to this part of the world, as it should and surely will.