Big, baffling and bounteous: The marine mammal collection at the South Australian Museum

Abstract

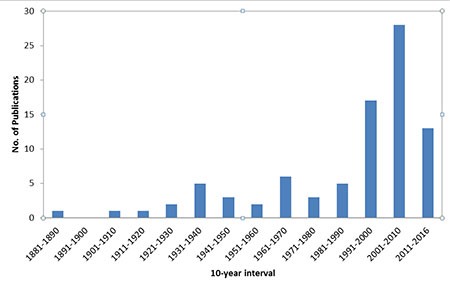

The South Australian Museum’s marine mammal collection began in the late 1800s and has benefited since from the keen influence of directors, curators and researchers. It is now the largest and most comprehensive in Australia, numbering over 2200 specimens and 59 species. Research emanating from the collection has contributed substantially to the understanding of the biology of Australia’s marine mammals and their conservation. A unique preparation facility uses efficient processes and results in high-quality specimens. Marine mammals are included in five displays that engage the visitor to the museum and staff and honorary researchers are frequently in the media through the focus of their work. The collection and its associated data are researched by museum, national and international scientists. At least 90 scientific publications have been written using museum specimens, over half of these since 1990 when the collection underwent considerable expansion.[1]

History

In 1881, the South Australian Museum sent newly appointed taxidermist, George Beazley, and a collecting team to recover the skeleton from an adult sperm whale that had washed up at Point Bolingbroke, near Port Lincoln, South Australia. The task was extremely difficult because the whale was very big – a full-grown male measuring 18.7 metres – and it needed to be flensed, disarticulated and transported by ship to Adelaide. The skeleton was then cleaned by maceration, whereby flesh rots off the bones in water. The sperm whale skeleton is still on display at the front of the museum on North Terrace, Adelaide. Two years after the sperm whale was collected, an unusual whale washed up on the Yorke Peninsula and its skeleton was purchased for display. As with many museum specimens, it baffled those who attempted to identify its species. It wasn’t until 1971 that Peter Aitken, Curator of Mammals, confirmed it as a Bryde’s whale.[2] One of the primary roles of museum natural history collections is to ‘vouch for’ an animal being recorded at a certain date and place, and to be able to verify its species identification over time. The Bryde’s whale from the Yorke Peninsula is a case in point even though its identification took 88 years.

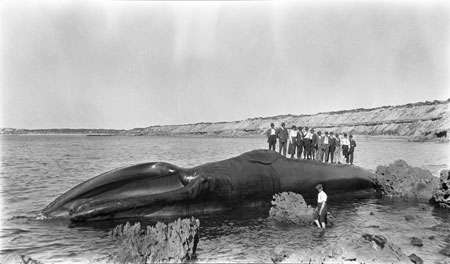

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, museums around the world collected large whale skeletons primarily for display, because they were a major drawcard for visitors, thus increasing a museum’s visibility in the public’s eye. Their gargantuan size, unusual body form and the mysterious environment in which they lived elicited a sense of wonder.[3] To add to this, there was also the intrigue of stories depicting the thrill and danger of hunting told by whalers. In 1918, Edgar Waite, Director of the South Australian Museum, organised the collection of an Antarctic blue whale (subspecies Balaenoptera musculus intermedia) from the remote Corvisart Bay on the west coast of Eyre Peninsula.[4]

photograph by Edgar Waite, South Australian Museum

Antarctic blue whales are now listed as endangered by the Commonwealth and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), so this specimen is very valuable scientifically. Few specimens are held by Australian museums and only three articulated skeletons are displayed.[5] Like the sperm whale collected at Point Bolingbroke, the blue whale must have been a massive and difficult undertaking.[6] Barrels of oil collected from rendered blubber were stored at Port Adelaide, with the hope of securing financial gain from its sale, which did not eventuate.[7] Recouping some of the expenses of the collecting expedition was probably the purpose of this proposed venture. The cleaned blue whale skeleton was not suitable for display because many of the bones were broken at the time of stranding. In addition, the skull was dropped from the gantry while attempting to move it at the museum after it had been prepared. With nowhere to store the disarticulated specimen at the museum, the bones were housed in the School of Mines 200 metres along North Terrace. Sadly, all that remains of this specimen in the mammal collection today are the right side of the lower jaw (on display), two ear bones, some tail vertebrae and the bones from both flippers.

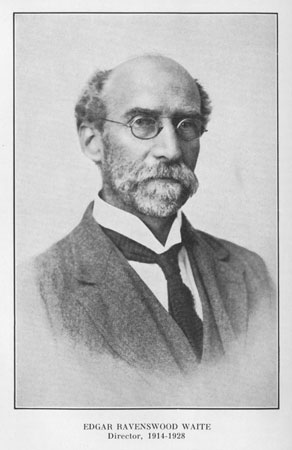

South Australian Museum

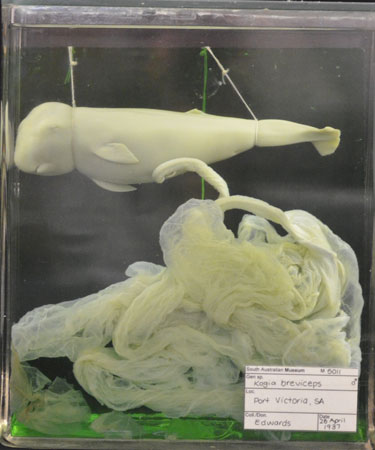

Of the directors who have influenced the collection, perhaps the most influential in the early days was Edgar Waite. Originally from Yorkshire, Waite held museum positions in zoology at Leeds (United Kingdom), the Australian Museum (Sydney) and Christchurch (New Zealand) before becoming Director of the South Australian Museum for 24 years from 1914. Waite was a scientist with an interest in diverse animal groups, including whales and dolphins, and he realised the importance of collecting for scientific study, not just display. Research collections are considered more useful if they have broad taxonomic coverage so Waite and directors who followed him took advantage of stranded animals to augment the South Australian Museum’s collection. Herbert Hale (Director of the museum from 1931 to 1960) and John Ling (Director 1973–1983) also had considerable influence on shaping the marine mammal collections and research at the museum. Hale combined an interest in fishes with cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises). He was a keen collector of unusual species such as the pygmy right whale, pygmy sperm whale and species in the beaked whale family and he wrote several scientific publications on them.[8] Like Waite, Hale realised the importance of collecting for scientific study and many of the specimens he acquired for the South Australian Museum became the cornerstone of the collection ‘behind the scenes’. He also knew that it was necessary to collect body parts, in addition to the skeleton, to describe the life history of species. The foetus of a pygmy sperm whale collected from a pregnant female in 1937 is still admired by visitors to the mammal section of the museum. Hale summarised some of the noteworthy specimens acquired by the museum in The First Hundred Years, a special edition of the Records of the South Australian Museum.[9]

photograph by David Stemmer, South Australian Museum

John Ling studied both major groups of marine mammals, e.g. cetaceans and pinnipeds, while he was Director and Head of Science at the South Australian Museum. Although his focus was primarily live animal research, he also collected specimens and kept records of strandings and sightings of live animals that would later become the basis for two nationally important databases.

Two curators influenced the development of the marine mammal collection. Peter Aitken, Curator of Mammals (1964–1982) was instrumental in the procurement of the museum’s Bolivar facility (see below) and collected important cetaceans. I joined the museum in 1983 and at that time my specialty was small mammal biology. By 1990, my focus – indeed, passion – had turned to marine mammals, and the collection has grown from about 350 to more than 2200 specimens, which makes it the biggest collection of marine mammals in Australia. Whereas in the past the primary objective was to collect rare and unusual species, the collection now includes large numbers of common species such as bottlenose and common dolphins with their associated life history data. These specimens are vital to conservation research. For example, the large number of bottlenose dolphin skulls is being used to elucidate the taxonomy of this baffling group.10

It took a week and a half to flense the carcass and collect the skeleton and another two years to clean and degrease the bones

photograph by Peggy Rismiller, South Australian Museum

Since 1990, several other big whales have been added to the collection. The full skeleton of a 21-metre pygmy blue whale (subspecies Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda) was collected at St Kilda, 21 kilometres north of Adelaide during September 1989. While it might seem that, with modern equipment at hand, such a task would be straightforward, but not so for this carcass. It was towed to an inaccessible island because the local council did not want a mess on an urban beach. This forced the museum team and numerous volunteers to travel each day by boat during the two weeks it took to flense and dismember the carcass. In 2001, the museum gained much media attention when a team collected a 14-metre southern right whale from Head of Bight, South Australia. The unfortunate animal had wasted away following a long-line entanglement around its tail. In 2014, eight sperm whales stranded on mudflats on the western side of Gulf St Vincent, across from Adelaide. Museum staff and volunteers attended and collected the jaws of all seven females that died, as well as the full skeleton of one carcass. These events are good publicity for the museum because people are fascinated by the enormous size of whales and the effort that is involved in dissecting and studying them. They are also curious as to why the animals died and museum researchers attempt to determine this.

photograph by Leanne Wheaton

Seals and sea lions (pinnipeds) have also featured in the activities of the South Australian Museum since the early 1900s. Considerable effort was put into obtaining specimens of ‘true’ seals (Family Phocidae), perhaps because they are rarely seen on Australian shores. During the Australasian Antarctic Expeditions (AAE, 1911–1914) and British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expeditions (BANZARE, 1929–1931) almost 40 marine mammal specimens, mostly ‘true’ seals, were obtained for the museum.[11] In the past 40 years, field-based studies of fur seals and sea lions have contributed many specimens to the pinniped collection. These are significant collections because additional data on animal life history accompany them. Knowledge of species’ biology, including life history, over long periods of time is required for assessing conservation status.

Displays and education

photograph by A Treichel, South Australian Museum

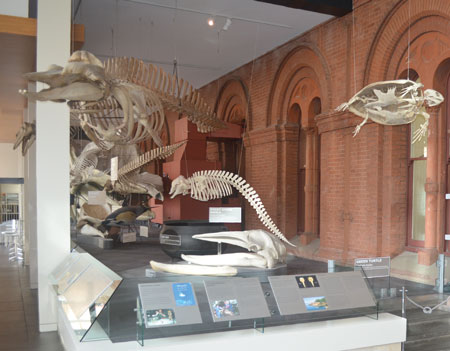

Displaying marine mammals has been one of the roles of the South Australian Museum since the late 1800s. Public galleries have undergone many changes, with early displays typical of museum displays in the Victorian era. Skeletons and mounts were hung in the light well of a two-storey building and very large skeletons were articulated in a rudimentary display ‘shed’ (really a cage with a roof) adjacent to the main museum buildings. During the early 1960s, the ‘north wing’, as it is known, was modernised and a large glass-enclosed display was filled with all the articulated cetacean skeletons. It was an eye-catching advertisement for the museum, especially at night when lighting accentuated the enormous forms.

photograph by Roman Ruehle, South Australian Museum

The present displays that incorporate marine mammals are the result of a major museum upgrade that opened in 2000. This included the addition of the Mawson Gallery depicting the life of Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson. It includes two leopard seal mounts collected during the AAE and BANZARE. A selection of whales and dolphins is displayed behind the appropriately named Balaena Café at the front of the museum. Most of the skeletons in this display were recycled from previous galleries but a few have been added, including an accurately-articulated pygmy sperm whale skeleton posed ‘logging’ at the surface of an imaginary sea. Interpretive panels bring the whale and dolphin skeletons to life with explanations of how species live and how they are studied. The display sets out to excite and educate visitors to the museum, and is used by primary, secondary and university students.

photograph by David Stemmer, South Australian Museum

The entrance to the Science Centre, which houses many of the museum’s natural history specimens, has a display of a variety of vertebrates, including articulated skeletons of a leopard seal, a West Indian manatee and a dugong, as well as a beautiful cast of a dugong. The last was originally prepared as a mounted skin early in the museum’s history, but was cast during the 1960s because it had badly deteriorated. The Biodiversity Gallery, which opened in 2010, uses mounted skins to illustrate the differences between the Australian sea lion and two of the fur seal species found in South Australia.[12] In another section of this gallery there is a cast of a stranded Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin lying on a beach. In the ‘Giant squid’ exhibit, a cast of a newborn sperm whale illustrates this important predator of giant squids. Casts of whales and dolphins are important for the public to see because they provide a rare opportunity to show the whole animal up-close. They are also a good record of the fine detail of external anatomy for scientific investigations. The sheer difficulty of preserving and displaying or storing the whole body of a marine mammal means that this is rarely undertaken by museums.[13]

Whales have sometimes been displayed temporarily at the South Australian Museum. The pygmy blue whale that stranded at St Kilda, north of Adelaide, in 1989 created a great amount of public interest while it was being collected by the museum. From the point of view of the museum, the purpose of displaying the skeleton for several months in 1994 was several-fold. Firstly, it illustrated what becomes of a whale skeleton after it is collected and prepared, so for the public this was timely and topical feedback for their curiosity. Secondly, information on blue whales and their conservation status were included in the exhibition, thus incorporating an educational aspect to the display. Thirdly, it promoted the South Australian Museum (and its unique preparation facilities) as one of the major institutions for marine mammal collections and research in the Southern Hemisphere.

photograph by SA Jarvis, South Australian Museum

Science education, including that related to marine mammals, is an important role for the South Australian Museum. This is accomplished through a program for primary and secondary students, university lectures and postgraduate supervision. Community education is also undertaken through lectures to community groups, tours of facilities and the travelling outreach program. Involving other organisations in fieldwork is also an excellent way to educate the public and promote the research of the museum. A good example is the joint exercise with the Australian and New Zealand Scientific Exploration Society in 1994 during which the bones of the endangered southern right whale were exhumed at Fowlers Bay, South Australia.[14] These were the remains of whaling operations that explorer Edward John Eyre had observed in 1840. Several very important specimens of right whales were collected for the museum. Volunteers who assist with collection management in the marine mammal collection are another form of community education. They not only learn about the relevance of the collection, they tell friends and relatives what goes on, thus spreading the word for the museum. Unfortunately, there is still the perception by many in the community that specimens are ‘put on the shelf and never looked at again’. In this day of dwindling government funding, it is crucial that politicians also see the value of museum research to the economy and human well-being. What better way of sparking interest in marine mammals than showing people how we go about collecting a large whale? It is amazing that people never seem to tire of hearing stories about our research on these enormous creatures. Perhaps it is because we are seen as a bit quirky!

Facilities and collections

Collecting, preparing and storing marine mammal skeletons is labour-intensive and expensive, and special facilities are required to do these tasks justice. For these reasons, many museums shy away from major programs of augmenting such collections. Before 1980, the South Australian Museum was in the same predicament. Preparation of large and smelly items was carried out either at the museum in the city or in an old farmhouse at Bolivar, conveniently located on the sewage works property 20 kilometres north of Adelaide. In 1983, a purpose-built facility was opened at Bolivar and museum preparators Winston Head and Peter Corkeron and curator of mammals Peter Aitken were instrumental in its design. The Bolivar facility is the envy of marine mammal scientists who visit it – there is no other preparation facility of its size in the world. Among its many unique features was a custom-built degreasing machine that used boiling trichloroethylene to remove oil from the porous bones so typical of whales and dolphins. Unfortunately, this machine is no longer in use as it was deemed environmentally unsafe and to bring it up to standard was beyond the museum’s budget. David Stemmer, the present collection manager, is experimenting with less toxic chemicals and better processes for degreasing vertebrate bones. Other features at the Bolivar facility include large, heated macerating tanks and a gantry crane that can lift animals that weigh up to 5 tonnes. Animal weight is a key datum required when describing growth and maturity of marine mammal species, and it is rarely measured. A limiting factor is that first the whale needs to be transported to the facility which is a feat in itself. The heaviest animal weighed at the facility was a 1.95 tonne juvenile humpback whale.

photograph by Denis Smith, South Australian Museum

Adjacent to the preparation building is a large shed that houses a bounteous collection of cetacean baleen, teeth, skulls and post-cranial skeletons. Built in 1996, it replaces the many inadequate storage facilities that the South Australian Museum has rented over time. Specimens range from single teeth to 4–5 metre skulls of blue and southern right whales. Many of the specimens are represented by full skeletons for each individual but for large species there are fewer examples.

photograph by Denis Smith, South Australian Museum

How difficult a specimen is to obtain depends on many factors, such as remoteness, geographical features and size of the animal. It took a team of 18 people eight days to collect the skeleton of the 14-metre southern right whale on a remote beach at Head of Bight, South Australia, in 2001, yet only three days to collect a 17-metre fin whale from the mudflats at Parham just north of Adelaide in 2009. Once back at the museum’s Bolivar facility, it takes up to 18 months to macerate and clean the skeletons of large whales before they are registered into the collection.

Cleaning rotting flesh off skeletons is not to everyone’s liking but our staff and volunteers find it fun!

photograph by David Stemmer, South Australian Museum

Row on row of dolphin skulls, large and small boxes of disarticulated skeletons, boxes of sperm whale teeth, huge lower jaws of baleen whales and neatly lined-up vertebrae of large whales greet the visitor to the collection. Each specimen is assigned a unique registration number when it is accessioned into the collection and all parts of the skeleton are labelled with this number to avoid mixing up individuals. We are often asked: ‘Why do you need more than one or two of each kind?’ The answer, obvious to a scientist, perhaps needs some explanation to others: animals are variable in size and appearance and an adequate statistical sample is required to arrive at a meaningful description of each species. Baleen plates, used to sieve the plankton and small fish from the ocean, are an integral part of a baleen whale specimen but are not well-represented in museum collections because they are difficult to prepare and store. The aim of the South Australian Museum is to retain both sets of baleen from each specimen whenever possible. As a result, its collection is the best in the Southern Hemisphere. Baleen is stored in a recycled shipping container that was made insect-proof to protect it from damage by webbing clothes-moths and carpet beetles.

All non-cetacean marine mammal specimens are stored in the Science Centre, adjacent to the public galleries of the museum, or at an off-site store in suburban Adelaide. The pinniped collection has representatives of all 10 species recorded in Australian waters, as well as some from elsewhere (Table 1, 2). The number of Australian sea lion specimens is over 450, the largest single collection of this endemic and endangered Australian species in the world. Several collections of pinnipeds from the subantarctic have been donated to the museum and these have become valuable sources of information for recent research on the taxonomy of fur seals worldwide.[15]

There are 4 species of cetacean recorded from Australian waters and 41 of these are in the collections of the South Australian Museum. Among the cetacean specimens are species that are unique to Australia and therefore very important nationally and internationally. Full skeletons of several adult or near-adult whales, for example fin whales and southern right whales, are the only such examples from Australia. The South Australian Museum holds the one mainland example of each of the Ross seal, Weddell seal, spectacled porpoise and Omura’s whale. In addition to unique items, the collection contains the largest number of several noteworthy species, for example nine southern bottlenose whales, 58 pygmy right whales and 61 strap-toothed whales.

| Group | Species | Registered specimens |

|---|---|---|

| Cetaceans | 42 | 1283 |

| Pinnipeds | 14 | 969 |

| Sirenians | 2 | 23 |

| Other | 1 | 6 |

| Total | 59 | 2281 |

|

Pinnipeds |

||

|

Eared seals |

Arctocephalus forsteri |

long-nosed fur seal |

|

Arctocephalus gazella |

Antarctic fur seal |

|

|

Arctocephalus pusillus |

Australian fur seal (brown fur seal) |

|

|

Arctocephalus tropicalis |

subantarctic fur seal |

|

|

Neophoca cinerea |

Australian sea lion |

|

|

Phocarctos hookeri |

New Zealand sea lion (Hooker’s sea lion) |

|

|

Zalophus californianus |

California sea lion |

|

|

‘True’ seals |

Hydrurga leptonyx |

leopard seal |

|

Leptonychotes weddellii |

Weddell seal |

|

|

Lobodon carcinophaga |

crabeater seal |

|

|

Mirounga leonina |

southern elephant seal |

|

|

Ommatophoca rossii |

Ross seal |

|

|

Phoca vitulina |

harbour seal |

|

|

Walrus |

Odobenus rosmarus |

walrus |

|

Cetaceans |

||

|

Baleen whales |

||

|

Right whales |

Eubalaena australis |

southern right whale |

|

Pygmy right whale |

Caperea marginata |

pygmy right whale |

|

Rorquals |

Balaenoptera acutorostrata |

dwarf minke whale |

|

Balaenoptera bonaerensis |

Antarctic minke whale |

|

|

Balaenoptera borealis |

sei whale |

|

|

Balaenoptera edeni |

Bryde’s whale |

|

|

Balaenoptera musculus |

blue whale |

|

|

Balaenoptera omurai |

Omura’s whale |

|

|

Balaenoptera physalus |

fin whale |

|

|

Megaptera novaeangliae |

humpback whale |

|

|

Toothed whales and dolphins |

||

|

Dolphins and small whales |

Delphinus delphis |

short-beaked common dolphin |

|

Feresa attenuata |

pygmy killer whale |

|

|

Globicephala macrorhynchus |

short-finned pilot whale |

|

|

Globicephala melas |

long-finned pilot whale |

|

|

Grampus griseus |

Risso’s dolphin |

|

|

Lagenorhynchus cruciger |

hourglass dolphin |

|

|

Lissodelphis peronii |

southern right-whale dolphin |

|

|

Orcaella heinsohni |

Australian snub-fin dolphin |

|

|

Orcinus orca |

killer whale (orca) |

|

|

Pseudorca crassidens |

false killer whale |

|

|

Sousa sahulensis |

Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin |

|

|

Stenella attenuata |

pantropical spotted dolphin |

|

|

Stenella coeruleoalba |

striped dolphin |

|

|

Stenella longirostris |

spinner dolphin |

|

|

Steno bredanensis |

rough-toothed dolphin |

|

|

Tursiops aduncus |

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin |

|

|

Tursiops truncatus |

common bottlenose dolphin |

|

|

Small sperm whales |

Kogia breviceps |

pygmy sperm whale |

|

Kogia sima |

dwarf sperm whale |

|

|

Sperm whale |

Physeter macrocephalus |

sperm whale |

|

Porpoises |

Phocoena dioptrica |

spectacled porpoise |

|

River dolphins |

Platanista gangetica |

South Asian river dolphin |

|

Beaked whales |

Berardius arnuxii |

Arnoux’s beaked whale |

|

Hyperoodon planifrons |

southern bottlenose whale |

|

|

Mesoplodon bowdoini |

Andrews’ beaked whale |

|

|

Mesoplodon grayi |

Gray’s beaked whale (Scamperdown whale) |

|

|

Mesoplodon hectori |

Hector’s beaked whale |

|

|

Mesoplodon layardii |

strap-toothed whale |

|

|

Mesoplodon densirostris |

Blainville’s beaked whale |

|

|

Mesoplodon ginkgodens |

ginkgo-toothed beaked whale |

|

|

Tasmacetus shepherdi |

Shepherd’s beaked whale (Tasman beaked whale) |

|

|

Ziphius cavirostris |

Cuvier’s beaked whale (goose-beaked whale) |

|

|

Sirenians |

||

|

Dugongs |

Dugong dugon |

dugong |

|

Manatees |

Trichechus manatus |

West Indian manatee |

|

Other |

Ursus maritimus |

polar bear |

In addition to the traditional collection items of skulls, skeletons, baleen and teeth, the South Australian Museum has put considerable effort into retaining other parts of the carcasses that are collected, particularly since 1985. This is largely due to a necropsy program involving the monitoring of marine mammal mortalities in South Australia and the research interests of the scientists associated with the mammal section. A generous and knowledgeable mentor, Graham Ross, had a significant influence on me during the first 10 years of the collection’s redevelopment. Since the late 1980s, frozen organ samples from over 1000 animals have been archived for toxicology studies, and a similar number for genetic studies have been integrated into in the Australian Biological Tissue Collection at the South Australian Museum. Fixed tissues for pathology research have been collected and archived, as have many histological slides that are prepared from these. The histology collection numbers 3200 microscope slides. Parasites are curated by the appropriate section of the museum. Stomach contents have been retained and catalogued, and reproductive organs collected and fixed in formalin, then transferred to ethanol for long-term storage.

A photographic collection of the examined carcasses provides information on external appearance, including injuries. This is particularly relevant for marine mammals because the whole body is rarely retained intact. Images of live stranded and dead marine mammals are also catalogued as a permanent and verifiable record of events.

Details and images of sightings of live marine mammals are also verified and catalogued as non-specimen records. These and the specimen records form the basis of the state species listing and distribution maps found in the Census of South Australian Vertebrates.[16] The museum has recently completed a federally-funded project to upgrade the South Australian Whale and Dolphin Sighting Database and provide records to national databases such as the Atlas of Living Australia.[17]

photograph by Elizabeth Steele-Collins

The museum maintains the cetacean stranding database for South Australia which includes records for which there are no specimens held in its collections. It is not traditionally the remit of a museum to curate a non-specimen database for a state or territory government but for two reasons it was deemed a logical undertaking. The first is that there are often images accompanying the records and these should be appropriately archived. The second is that there is extensive expertise in identifying marine mammals at the museum. The data contribute to the annual reports of cetacean mortalities and live strandings prepared by the South Australian Museum for the Commonwealth, on behalf of the state government.

In association with other specialists, a National Marine Mammal Aging Facility has been established at the museum to estimate the age of cetaceans and pinnipeds through analysis of layers in tooth dentine. Age is a crucial factor to incorporate in studies of marine mammal biology.[18] Estimating the age of dolphins by tooth structure uses microscope slides of stained, thin-sectioned teeth. To date, over 500 dolphins of two species have been included in this part of the collection. Students and visiting researchers have made use of the laboratory and expertise provided by the museum.

photograph by Jane McKenzie

Relevance and impact of the research collection

Studying marine mammal collections, with the exception of tissue samples for genetic and/or toxicology studies, is problematical for researchers because the specimens are large and almost impossible to send out for loan. Scientific studies on the skulls and skeletons are therefore more limited than for other groups of organisms that museums hold. Marine mammal researchers are generally required to make expensive and time-consuming visits if they do not reside in South Australia and this somewhat limits the use of the specimens.

The first scientific publication on the South Australian Museum’s marine mammal collection appeared in 1889.[19] It, and most of the articles that followed in the next almost 100 years, were descriptive in nature. They listed species found in South Australia drawing on the museum collection to vouch for presence, and they presented details of stranded cetaceans and their skeletons. Since about 1990 there has been a considerable increase in the number of publications and the focus has changed to a more interrogative approach. Modern science relies on sufficient ‘sample sizes’ to find robust answers to research questions. The museum’s marine mammal collection not only has hundreds of dolphins to study, but each one also has a suite of data that provides a full picture for an individual. ‘Whole animal biology’ is gathering popularity in scientific circles because it does not look at factors in isolation.

Catherine Kemper/South Australian Museum

More use has been made of the collection and its data because of increased accessibility through national databases and because it has been promoted widely to the scientific community.[20] Expansion of the collection since the mid-1980s has also been an important factor. In addition, several honorary researchers have joined the marine mammal team and postgraduate students have been encouraged to use the collections for their studies.

Researchers at the South Australian Museum have been called upon to help solve the problem of dolphins dying in finfish aquaculture sea cages. [21] After the completion of the study, recommendations were made to industry that helped reduced the number of mortalities and a code of practice was introduced. Museum researchers also work closely with wildlife law enforcement agencies regarding intentional killing of marine mammals.[22] Shotgun pellets and rifle bullets are retrieved and provide proof of these activities. It is possible to identify the weapon used in the crime. Intense media attention is associated with cases of killing dolphins and seals and, because the museum and its associates investigate these, it acts as a deterrent to would-be perpetrators.

Taxonomy, systematics and distribution are generally considered the mainstay of museum research but in the case of the South Australian Museum’s marine mammal collection, its size and breadth has enabled expansion into other fields. For example, research describing the concentrations of heavy metals in South Australian dolphins has put the museum at the forefront of this field in Australia.[23] Investigations are underway that may link disease to high levels of these contaminants. Since humans are apex predators like dolphins and we share some foods, there are obvious implications for our health. Stomach contents collected from hundreds of dolphins and pinnipeds have led to a better knowledge of the diet of these groups than anywhere in Australia.[24] Life history traits, such as when a species is weaned and sexually mature, have been described for common species.[25] Disease and cause of death have been investigated through a program of post-mortems conducted on almost all carcasses that are collected for and by the museum.[26] Monitoring mortalities and their causes has obvious implications for conservation of species because it can identify perturbations in the pattern over time. Thus the research carried out using the South Australian Museum’s marine mammal collection assists the conservation and management of species and marine environments. This is very relevant in a society that expects environmental sustainability.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.Endnotes

1 I would like to acknowledge David Stemmer and previous collection managers for their commitment to maintaining the mammal collection. David also assisted with preparing the species lists and commented on the manuscript. I thank the many volunteers who have assisted with the collection of specimens and collection management. I am indebted to the National Parks and Wildlife, South Australia staff who have collected specimens over many years. I would also like to thank Peter Shaughnessy for his helpful comments on drafts of the paper, and Jenni Thurmer for her assistance with image scanning.

2 A Zietz, ‘A list of the whales and dolphins of the South Australian coast in the Public Museum, Adelaide’, Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, vol. 13, 1889, 8–9; H Hale ‘The first hundred years of the South Australian Museum 1856–1956’, Records of the South Australian Museum, vol. 12, 1956, 1–225; PF Aitken ,’Whales from the coast of South Australia’, Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, vol. 95, no. 2, 1971, 95–103.

3 S Greenblatt, ‘Resonance and wonder, Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 43, no. 4, 1990, 11–34.

4 ER Waite, ‘Two Australasian blue whales with special reference to the Corvisart Bay whale’, Records of the South Australian Museum, vol. 1, no. 2, 1919, 157–68.

5 TK Yamada, C Kemper, Y Tajima, A Umetani, H Janetzki & D Pemberton, ‘Marine mammal collections in Australia’, in Tomida et al. (eds) Proceedings of the 7th and 8th Symposium on Collection Building and Natural History Studies in Asia and the Pacific Rim, National Science Museum Monographs 34, 2006, pp. 117–26.

6 See Waite, ‘Two Australasian blue whales’, for an interesting commentary on the process.

7 Hale, ‘The first hundred years’.

8 Examples of Hale’s publications include HM Hale, ‘Pigmy right whale (Caperea marginata) in South Australian waters, Part 2’, Records of the South Australian Museum, vol. 14, no. 4, 1964, 679–94; and HM Hale, ‘The pigmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) on South Australian coasts, Part III’, Records of the South Australian Museum, vol. 14, no. 2, 1962, 197–229; see also FJ Mitchell, ‘Obituary and bibliography of Herbert Mathew Hale, OBE, 1895–1963’, Records of the South Australian Museum, vol. 15, no. 1, 1965, 1–8.

9 Hale, ‘The first hundred years’.

10 M Jedensjö, CM Kemper & M Krützen, ‘Cranial morphology and taxonomic resolution of some dolphin taxa (Delphinidae) in Australian waters, with a focus on the genus Tursiops’, Marine Mammal Science, in press.

11 PD Shaughnessy (ed.), ‘Antarctic seals, whales and dolphins of the early twentieth century: Marine mammals of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911–14 (AAE) and the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition 1929–31 (BANZARE)’, ANARE Reports, vol. 142, 2000.

12 R Morrison, ‘The biodiversity gallery, South Australian Museum’, reCollections, vol. 5, no. 2, 2010, http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_5_no_2/commentary/the_biodiversity_gallery_south_australian_museum.

13 AE Parr, ‘Concerning whales and museums’, The Smithsonian Report for 1963, 1964, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 1964, pp. 499–502.

14 CM Kemper & CR Samson, ‘Southern right whale remains from 19th century whaling at Fowler Bay, South Australia’, Records of the South Australian Museum, vol. 32, no. 2, 1999, 155–72.

15 S Brunner, ‘Fur seals and sea lions (Otariidae): Identification of species and taxonomic review’, Systematics and Biodiversity, vol.1, no. 3, 2004, 339–439.

16 www.environment.sa.gov.au/Science/Information_data/Census_of_SA_vertebrates.

18 CM Kemper, E Trentin & I Tomo, ‘Sexual maturity in male Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus): evidence for regressed/pathological adults’, Journal of Mammalogy, vol. 95, no. 2, 2014, 357–68.

19 Zietz, ‘A list of the whales and dolphins of the South Australian coast’.

20 Yamada, Kemper,et al., ‘Marine mammal collections in Australia’.

21 CM Kemper & SE Gibbs, ‘Dolphin interactions with tuna feedlots at Port Lincoln, South Australia, and recommendations for minimising entanglements’, Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, vol. 3, 2001, 283–92.

22 CM Kemper, A Flaherty, SE Gibbs, M Hill, M Long & RW Byard, ‘Cetacean captures, strandings and mortalities in South Australia 1881−2000, with special reference to human interactions’, Australian Mammalogy, vol. 27, 2005, 37–47; RW Byard, CM Kemper, M Bossley, D Kelly & M Hill, ‘Veterinary forensic pathology: The assessment of injuries to dolphins at post-mortem’, Forensic Pathology Reviews, vol. 4, 2006, 415–33.

23 PJ Lavery, CM Kemper, K Sanderson, CG Schultz, P Coyle, JG Mitchell & L Seuront, ‘Heavy metal toxicity of kidney and bone tissues in South Australian adult bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus)’, Marine Environmental Research, vol. 67, 2009, 1–7; T Lavery, N Butterfield, CM Kemper, RJ Reid & K Sanderson, ‘Metals and selenium in the liver and bone of three dolphin species from South Australia, 1988–2004’, Science of the Total Environment, vol. 390, 2008, 77–85.

24 SE Gibbs, RG Harcourt & CM Kemper, ‘Niche differentiation of bottlenose dolphin species in South Australia revealed by stable isotopes and stomach contents’, Wildlife Research, vol. 38, 2011, 261–70.

25 Kemper, Trentin & Tomo, ‘Sexual maturity in male Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins’.

26 Kemper, Flaherty et al., ‘Cetacean captures, strandings and mortalities in South Australia 1881−2000’; I Tomo, CM Kemper & PJ Lavery, ‘18-year study of south Australian dolphins shows variation in lung nematodes by season, year, age class and location’, Journal of Wildlife Diseases, vol. 46, no. 2, 2010, 488–98.