design by Couch Creative

National Museum of Australia

League of Legends: 100 Years of Rugby League in Australia opened on 8 March 2008 at the National Museum of Australia to coincide with the launch of the 2008 National Rugby League (NRL) season. Celebrating the centenary of the game, the exhibition traced the history of rugby league since its emergence as a breakaway code from rugby union in Sydney in 1908. Curating this exhibition represented a wonderful conjunction of professional interest and personal enthusiasm for me. Professionally, the exhibition brought the opportunity to present an exhibition on a significant part of Australian social and cultural history. On a personal level, delving into the history of rugby league was like a journey home. I had grown up in the western suburbs of Sydney in the 1970s and 1980s, following and playing both rugby union and rugby league. I had spent many Sunday afternoons watching teams clash at suburban grounds around Sydney. Although a mediocre player, I managed to achieve the status of a passionate fan.

In this article I review the development of the League of Legends exhibition. I discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using anniversaries as a peg on which to hang your exhibition hat, and consider the question of whether the history of rugby league was an appropriate topic for the National Museum of Australia. I also examine some of the particular challenges of collecting and exhibiting sporting material culture. Producing an exhibition on sports history raises some fundamental interpretative issues, including the use of memorabilia, the balance of static displays versus interactive elements, and the use of photographic archives and audiovisual material. As a travelling show, League of Legends posed some major logistical challenges that I will also explore. Audience was another important issue for this exhibition, with the subject matter on display attracting visitors not normally considered part of the National Museum's traditional constituency. Finally, I will conclude the article with a discussion of the evaluation of the exhibition conducted by the museum.

When I commenced work on the League of Legends project in 2006 I was fully aware that my enthusiasm for rugby league, while shared by a large proportion of the populations of New South Wales and Queensland, is not shared by everybody. The great football schism that divides Australia between advocates of Australian Rules football and the two rugby codes means that there is little interest in rugby league in Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia. The game's numerous examples of on-field violence, and of young men behaving badly off-field, lead many to dismissively refer to the game as 'thugby'. Some colleagues argued that the history of rugby league sat awkwardly with the Museum's mission. The institution is committed to exploring Australian social history and popular culture, but did rugby league deserve such attention? Surely, it was put to me, rugby league receives more than its fair share of attention in newspapers and television? Could producing an exhibition celebrating the centenary of the game become a marketing exercise promoting the NRL rather than an act of producing history?

These questions were raised repeatedly throughout the life of the project. As the lead curator, I took these issues seriously. I was, however, convinced that delivering an exhibition on the history of rugby league was a worthwhile undertaking. While rugby league is often ugly, I believe there is much more to the game than what appears on the front and back pages of the paper. In curating League of Legends, I set myself the goal of producing an exhibition that would not only appeal to the rugby league faithful, but would also spark the curiosity of anyone interested in Australian social history.

The exhibition was made possible by the coincidence of a number of factors. The first of these was that sport had been identified as underrepresented in the Museum's programs by the Review of the National Museum of Australia which had been conducted in 2003.[1] This finding provided an impetus for the Museum to collect and exhibit sporting material. One of the first major objects purchased as a result of the new emphasis on sport was the Royal Agricultural Society Challenge Shield, a beautiful mahogany shield associated with the first full year of competition of the New South Wales Rugby Football League. Aware that the museum had acquired this icon of the game, the head of the NRL, David Gallop, approached the Museum's director, Craddock Morton, about the possibility of jointly developing an exhibition to celebrate the centenary of rugby league in 2008. Fortuitously there was space in the exhibition calendar and suitable collection material available for the exhibition. The fact that Morton is a long-time Canberra Raiders supporter with a strong interest in rugby league assisted in moving the project from an idea into reality. I list these factors to illustrate the matrix of considerations that underpin a decision to proceed with an exhibition. The internal logic of an exhibition proposal is important but, in the end, external factors can determine whether an idea sees the light of day. This is a valuable lesson for all curators working within institutions. The freedom to develop exhibitions is dependent on the mandate of the institution. This is a fundamental difference between the practice of history in the academy and within museums. While an independent scholar or academic can embark on writing a monograph on a subject of their choice, a curator who wishes to produce an exhibition is dependent on winning the backing of their institution.

Given that the decision to develop exhibitions can be political and, at times, opportunistic, curators must be able to answer the question of whether a project has historical merit independent of the forces that have brought it into being. In the case of League of Legends, the threshold question for me was: Did the centenary of rugby league justify the resources required by the National Museum of Australia to produce a major exhibition? From a social history perspective this was not a difficult case to make. Rugby league has been the dominant code of winter football in New South Wales and Queensland for most of the twentieth century. Developments within the code parallel changes in Australian society and history. Virtually all the major topics of contemporary Australian historiography can be found in the history of rugby league. The growth of the labour movement in the late 1890s is played out in the call for the professionalisation of sport. Class politics is played out in the split between the two rugby codes. Transnationalism can be traced in the influence in Australia of the professionalisation of rugby in Britain and the flow of players and ideas between the two countries. Issues of race are found in the history of the involvement of Indigenous players and migrants. Debate in Australian society over Australia's involvement in the First World War is reflected in the controversy over the continuation of the game during wartime. The impact of globalisation and changes in media ownership in the late twentieth century are seen in the struggle between media moguls over broadcast rights to games in the mid-1990s. Rugby league also provides a window into gender politics and the construction of Australian masculinity. This list of topics demonstrates how the history of rugby league is a window into how Australia has changed over the last century.

While the history of rugby league is clearly significant and worthy of further investigation, the question arises as to whether developing an exhibition in the context of a year of centenary celebrations makes for good history? Does the overriding framework of celebrating such a year make it difficult to produce a critical history of the game? Also, how does one manage the expectations of the major stakeholders involved in celebrating the centenary? From the very first days of the League of Legends project it was apparent that its success was dependent on gaining access to collections held by the Australian Rugby League (ARL), football clubs and the families of players. Each of these groups had strong views on how their history should be presented. In addition, the NRL was keen to exploit marketing opportunities associated with celebrating the game's history. Negotiating a balance between the interests of stakeholders and the production of a historical account of the game was a major challenge.

Historian and curator Marion Stell highlighted these issues concerning centenary exhibitions in a review of the Museum's 2007 exhibition, Between the Flags: 100 Years of Surf Lifesaving. This exhibition celebrated the centenary of the surf life saving movement in Australia, and was produced in collaboration between the Museum and Surf Life Saving Australia. Describing Between the Flags as 'safe and unchallenging', Stell asked: 'What will our national or state museums jump at next? Are there some organisations that would be judged unsuitable, and by whom?'[2] For Stell, there is clearly a danger that partnerships with external bodies celebrating major anniversaries have the potential to compromise the type of history produced.

While Stell's description of the content of Between the Flags may be contested, it is true that external partners bring with them expectations that influence the development of exhibitions. In relation to the centenary of rugby league, the danger was that the League of Legends exhibition could become a promotional exercise for rugby league rather than an exploration of the code's history. This issue was dealt with from the inception of League of Legends. In discussions with representatives of the NRL and the ARL, I emphasised that the Museum would insist on editorial independence in the development of content. This position was strengthened by the fact that the Museum did not seek any direct financial assistance from the NRL or ARL in the development of the exhibition. The exhibition, as such, was not dependent on external funding. The Museum's editorial independence was accepted without qualification and formally documented in a memorandum of understanding between the Centenary of Rugby League Committee (a body representing the interests of the ARL, the New South Wales Rugby League and the Queensland Rugby League) and the Museum.

This memorandum of understanding dealt directly with the issue as to who would control the development of content. I readily accepted the assumption that the centenary was a significant landmark in the history of the game and that celebration was appropriate. I also felt that the anniversary provided a powerful storytelling template that would help gain the interest of visitors. This did not mean that I looked at the history of the game through a lens of success, but rather that the 100th anniversary provided an opportunity to reflect on the history of the game, including its highs and lows.

An obvious constraint in the development of content for the exhibition was the availability of time and resources for research. The exhibition was due to open in early 2008. I saw my role as being to develop a storyline and identify objects. In order to come to terms quickly with the history of rugby league, I organised a workshop of journalists, writers and historians in early 2006. Held in a disused bar of the New South Wales Rugby Leagues Club, the walls of which were decorated with examples of rugby league memorabilia, this meeting was a brainstorming session that ranged freely over the history of rugby league. The group included Ian Heads, Sean Fagan, Geoff Armstrong and David Middleton, each of whom provided advice on the major milestones and personalities in the game's history.

I then undertook a survey of the secondary literature on the history of the game. It was immediately apparent to me that the breadth and quantity of subject matter would overwhelm any attempt to provide a detailed chronology within the space of a museum exhibition. Rather than undertake a comprehensive account of the game, I developed a storyline that combined elements of chronology with major themes. In the following description of the exhibition, I focus on the major objects displayed.

While I had chief responsibility for the development of the exhibition, the realisation of the final storyline represented the efforts of many people, including the design team, rugby league historians and other museum staff. The cliché that exhibition development is very much a team effort never seemed more apt.[3]

The first area encountered by the visitor to the League of Legends exhibition was the main hall of the National Museum. This large architectural space is striking, but it can also be difficult for the visitor to navigate. The challenge here is to attract visitors to the temporary exhibition gallery. In the case of League of Legends the designer created a wall that connected the interior of the gallery with the main hall. Inset into the wall next to the logo was a screen with an audiovisual loop of highlights of rugby league footage.

Having walked past the entrance wall, the visitor encountered the exhibition airlock that separates the temporary gallery from the main hall. The function of the airlock is to ensure that the environmental conditions inside the exhibition space are kept constant as visitors move in and out. While the space is unsuitable for the display of objects, it can be used to set the scene for exhibitions. During League of Legends, the airlock was used for a soundscape of a crowd roaring in the distance, interspersed with the voice of a stadium announcer. The soundscape was complemented by a wall treatment consisting of silhouettes of fans queuing for tickets. The source material for the soundscape was a set of recordings made at the Manly–Warringah versus South Sydney semifinal played at Brookvale in September 2007. These recordings added an authentic feel to the space and captured something of the experience of attending a game. In this sense, the airlock provided an immersive or emotional experience rather than an interpretative one, a liminal space in which the visitor could shift from the outside world into the space of the exhibition.

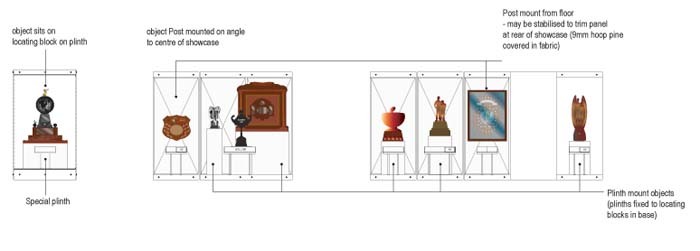

Once through the airlock the doors opened onto the exhibition proper. In any exhibition, this point is crucial to its overall success. The first impression that a visitor obtains of an exhibition space can determine their attitude to what follows. In the case of League of Legends, the visitor was confronted with an array of objects and trophies from the early years of the game. This module, entitled 'The game begins', explored the events in 1907 and 1908 that led to the commencement of rugby league in Australia. This key module explained the basis of the centenary being celebrated in 2008. It began with a display of photographs of the original nine foundation clubs, and displayed significant objects from the early years of the game, including the Royal Agricultural Society Challenge shield (the first premiership shield awarded in 1908), a jersey from the first Australian rugby league tour of England, and caps and medals belonging to Australian rugby league's first superstar, Dally Messenger. There were also objects associated with early advocates of the new code, JJ Giltinan and Victor Trumper.[4]

Considerable effort was made to ensure that the graphic panels did not disrupt the aesthetic experience of viewing the objects. In many exhibitions, an attractive object display can be destroyed by the presence of surrounding labels and graphics. In League of Legends, exhibition text was placed in an angled graphic trays located below the object. This allowed the visitor to have an uninterrupted view of the object, as well as allowing for more dramatic lighting effects as it separated the need to light the label text from the object. One of the problems of not placing labels directly adjacent to objects is that it can be difficult for visitors to find the relevant label text. The problem is compounded in dense displays featuring multiple objects. In the case of League of Legends, the exhibition designer solved this problem by positioning an identifying 'thumbnail' image of the object next to its relevant caption, allowing for quick identification of objects by the visitor.

Adjacent to 'The game begins' module was the 'Snapshots of glory' module. This was a photographic display, organised in chronological order. The photographs were selected to reflect the 100 years of the game, including great sporting moments, key personalities, fans and off-field controversies. In the Canberra venue, the photos were displayed in one continuous run, providing a timeline that took the visitor on a journey through a century of rugby league.

Supporting interpretative material for the trophies was displayed on angled graphic trays located below the eyeline of the objects. These trays were also used for the display of contextual audiovisual material. Small postcard-sized monitors were installed into the graphic trays, showing silent moving footage. This was a departure from more traditional display techniques where much larger monitors are used to show footage, sometimes overwhelming the object displayed and disrupting the aesthetics of the exhibit. Here, the object was given the highest priority with other graphic and visual elements placed literally at a lower level.

The intensity of the desire of players and fans to bring home the 'silverware' underpinned the power of the objects in this area. Each trophy was potentially a trigger point for a series of flashbacks and memories for visitors. I deliberately drew back from trying to over-interpret these objects. Much more important than the brief interpretative text provided were the memories of the exhibition visitors. Rugby league fans would in a sense provide their own interpretation and meaning of what they were looking at. Of course, for the 'non fan', the meaning of the trophies was significantly different. These visitors judged the trophies chiefly on their appearance. The display techniques provided room for both forms of interpretation.

The next module encountered in the exhibition was 'Controversy corner', a title borrowed from a weekly television panel discussion chaired by former player and sports broadcaster Rex Mossop. This module explored the way controversy has always been a feature of rugby league. From 1908 onwards, league has provided a steady supply of on- and off-field incidents that have dominated the news of the day. Player behaviour, referees' decisions and salary cap breaches have all fuelled a seemingly endless series of headlines. This module played an important role in the exhibition in that it explored the darker side of the game and helped balance the triumphal feel of other modules.

In the game's 100-year history many controversies invited exploration. In the end, three case studies were selected. The first focused on the role of referees. Utilising a 1970s referee's jersey, the text reminded the visitor of debates over the role of referees such as Greg 'Hollywood' Hartley, Barry 'Grasshopper' Gomersall and Bill Harrigan, all of whom became as famous, or infamous, as the elite players. The second case study explored in Controversy Corner was tobacco sponsorship. The display examined the long relationship between the tobacco company Rothmans and the NSWRL. The main object displayed here was a satirical poster produced by Sydney-based urban graffiti organisation, Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions (BUGA UP).

The controversy that stands out above all others in the history of rugby league is the Super League war of the mid-1990s, in which Kerry Packer's and Rupert Murdoch's rival media empires battled for control of the broadcast rights of the game. The war reached a climax in 1997 when, in what now seems a bizarre turn of events, 22 teams competed for premiership glory in two separate competitions. The exhibition featured the trophies from both competitions: the Super League Cup and Australian Rugby League's Optus Cup — reminders of how close the code came to self-destructing. The war eventually came to an end in 1998 with the creation of the NRL, the competition that is in place today.

Covering the Super League war posed an interpretative challenge because of the intensity of emotions involved and the complexity of events. Rather than attempt to retell the events of the Super League in detail, I made use of a mock trophy, sculpted by Sydney Morning Herald artist John Shakespeare, featuring the two major protagonists: Rupert Murdoch and Kerry Packer. Echoing the famous pose of John O'Gready's iconic 'Gladiators' photograph of two muddied players, taken just after the 1963 grand final, Packer is presented in the role of Norm Provan and Murdoch in the role of Arthur Summons. The celebrated embrace of two mates is transformed into a wrestling match with no holds barred. Shakespeare's depiction of the two moguls reveals the causes of the Super League war: a struggle for control of content between two media empires.

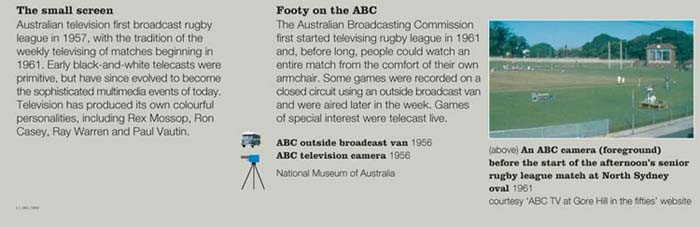

Interactive elements included a replica of a 1930s radiogram, built into a desktop. A large knob allowed the visitor to 'tune in' to examples of radio calls from different periods in rugby league history. Examples were drawn from both commercial and public radio, from both Queensland and New South Wales. For example, the visitor could select Tiger Black from 2KY calling a Test match between Australia and Great Britain in 1954, or Roy Slaven and HG Nelson's (comedians John Doyle and Greg Pickhaver) call of the 1988 grand final between Canterbury and Balmain, originally broadcast on 2JJJ.

Another interactive allowed visitors to select a favourite television moment from a menu of options. This included an excerpt from a Controversy Corner panel discussion about the 1981 grand final, featuring 'super' coach Jack Gibson (one of the most influential coaches in rugby league history), and broadcaster and former player Rex Mossop. Also included were memorable rugby league television ads, including Tina Turner's 'Simply the best', the 'I feel like a Tooheys' advertisement and Thomas Keneally's poem, 'Ode to rugby league', written at the height of the Super League war. Both the radio and television interactives were highly nostalgic displays, allowing the visitor to relive moments from their childhoods, including controversial grand finals, test football and the Super League war.

The League of Legends exhibition, in the format described above, was on display in Canberra for three months in 2008. During this period, the exhibition attracted nearly 40,000 people. The exhibition then travelled to the Queensland Museum, Brisbane, attracting more than 80,000 visitors over two months. After Brisbane, League of Legends travelled to Sydney at the time of the Rugby League World Cup, attracting more than 30,000 visitors (3 months); then to the Museum of Tropical Queensland, Townsville (over 20,000 visitors in 3 months); and finally to the National Sports Museum, Melbourne (over 30,000 visitors in 3 months).[6] The variation in visitor numbers from venue to venue depended on a range of factors, including the way the exhibition was marketed and whether an entry fee was charged. The exhibition achieved its highest visitor numbers in Canberra and Brisbane, where no entrance fee was charged.

Fifty exit interviews were conducted with visitors to the exhibition in Canberra.[7] The key finding was that visitors to League of Legends rated the exhibition highly. Seventy per cent of visitors surveyed rated League of Legends as 'very good' and 28 per cent rated it 'good', giving a total approval rating of 98 per cent. It should be noted in interpreting this high satisfaction rating that the majority of respondents were interested in rugby league (84 per cent) and had come to the Museum specifically to see the exhibition (72 per cent). In terms of audience composition, visitors were overwhelmingly male (82 per cent) and, of these. 62 per cent were aged between 25 and 49. There was also strong evidence that most visitors attended the exhibition in a group of either family or friends, with 76 per cent of respondents saying they had visited the exhibition with other people. Also of interest was the fact that the majority of the visitors had not been to other National Museum of Australia temporary exhibitions (58 per cent), suggesting that this exhibition had succeeded in attracting a new audience.

When invited to comment on what they liked about the exhibition, respondents emphasised the overview of the history of the game and the objects on display. Some of the objects elicited a nostalgic or emotional response. For example, 'The JJ Giltinan shield — I remember seeing it held high as a kid. Brought back tears to my eyes seeing it again, and I am pretty tough. Just brings it all back to you'.[8] There was also a strong indication of how the exhibition validated visitors' interest in rugby league. As one fan put it, 'Having all the trophies and cups together. Seeing the photos, and picking out family members. My uncle is there — that was a pleasant surprise'.[9] Negative comments often related to the personal interests of fans. For example, 'Could be bigger. More Parramatta stuff'.[10]

Respondents were asked what they thought was the exhibition's main message. The answers suggested that visitors considered the main intention of the exhibition was to convey the history of rugby league. For example: 'History sums it up. A game for the supporters, for families'. Some respondents emphasised how the history revealed change: 'It's a changing sport, a tough sport, evolving as a game to meet the expectations of the people who pay to go and see it'. Others saw it as a promotional exercise, saying that the exhibition would help to 'make more fanatics like us, It'll be around forever. Tradition. It's not going to stop'. [11]

Care needs to be taken in interpreting the visitor survey results, as the sample size is small and from a single venue. That said, a series of focus group discussions held with front-of-house staff confirmed and amplified the findings of the survey. These staff observed that visitors to the exhibition were noticeably different from more traditional museum-goers. In the words of one host, they were 'dudes with footy jumpers, and groups of young men'.[12] Hosts also commented that the visitors were unusual in that they came as experts in their own right. Their motivation for visiting the exhibition was not so much to learn about the history of rugby league, but rather to reinforce their own sense of pride in the game.

The front-of-house staff also noted that there was resistance by some museum visitors to the idea of a rugby league exhibition. In some cases when hosts suggested to museum visitors that they might like to see the exhibition, this was greeted with disdain. While some visitors are naturally uninterested in sport as a topic, another factor was ongoing media coverage of a series of controversies linking rugby league players with binge drinking and sexual assaults. The depth of this feeling was reflected in an anonymous comment written on a visitor feedback form at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney. When asked to record their favourite footy moment, the respondent had written, 'The day when Australia's flagship museum for design and technology funds an exhibition on piss-heads, thugs and rapists!'[13] No detailed interviews were carried out with visitors who expressed these concerns, so it is not possible to analyse their adverse response in greater detail. Clearly those who had strong negative feelings towards rugby league chose not to visit the exhibition.

While only a small proportion of visitors to League of Legends reacted negatively, such responses did raise the important question of whether the exhibition was presenting an overly celebratory view of rugby league. Had I, as curator, avoided the difficult questions of substance abuse and gender relations in the exhibition? In one sense the answer to this question was 'Yes', as the exhibition did not explore these issues in any detail. I would argue, however, that it was not the place to explore these issues. Providing a high level of prominence to a discussion of sexual assault allegations and substance abuse would have been unbalanced in the context of reviewing a century of history. The majority of visitors who were interested in the history of the game would have found such material offensive. That said, the exhibition did not exclude controversy. Photographs and newspaper headlines dealing with player behaviour were included in the loop of newspaper headlines provided in 'Controversy corner'. Some memorable incidents of violence were also included in photographs in the 'Snapshots of glory' module. These elements made it clear that there was a darker side to the game's history.

When reflecting on the League of Legends exhibition, a number of major lessons emerge for me. Firstly, the exhibition demonstrated the benefits of developing a shared vision between the curatorial and design teams. Acumen Design was able to significantly add to the appeal of the exhibition by making use of design motifs invoking leagues clubs, the locker room, grandstand and playing field. This was done in an understated way that did not overwhelm the exhibits they were supporting. The use of graphic trays below the sightline of objects also helped create an unobstructed view of the displays, allowing the aesthetic qualities of the objects to be fully appreciated. The clever positioning of large objects on longer sightlines helped ensure that visitors were drawn into the exhibition and rewarded with new and interesting vistas as they navigated the space.

From an audience perspective, League of Legends demonstrated that it is possible to attract a different audience to museum exhibitions. Prior to the opening of the exhibition, the museum did not know the degree of overlap between fans of the sport and regular museum visitors. Internal discussions within the museum before the opening of League of Legends suggested that the exhibition could fail to attract football fans because, to quote one colleague, 'they like to watch football, not go to an exhibition about it'. As it eventuated, there is clear evidence that the museum did attract a new audience. This is reflected in the way significantly more men visited than would normally be the case. A review of male and female response rates at National Museum of Australia temporary exhibitions over the last two years suggests that, on average, female visitors outnumber male visitors by 62 per cent to 38. For League of Legends the figure was 82 per cent male. Many respondents also indicated that this was the first temporary exhibition they had attended at the Museum. Again some caution needs to be taken in interpreting these figures due to the small size of the survey sample. It is true, however, that the high level of male visitation was also noted by front-of-house staff. These findings are consistent with the fact that rugby league is predominantly a male sport, both in terms of fans and player participation.

Returning to the question I raised at the beginning of the article: what kind of history was promoted in the League of Legends exhibition? Gaining the mandate and resources to undertake the development of the exhibition was primarily a political task. The development of the storyline and content was driven largely by the celebration of the centenary of the game. The subject matter on display was a function of the available material culture, and the audio and visual archive. From the perspective of one of the major exhibition stakeholders, the NRL, the exhibition was primarily a promotional exercise. Did these factors compromise the type of history being produced?

I would argue that the exhibition made a significant contribution to Australian sporting and cultural history. While it did not make any startling discoveries about rugby league history, it provided a powerful experience for fans of the game. This was not necessarily a learning experience in the didactic sense, but rather one of validation. The massing of objects, photographs and film provided a forum for visitors to reflect on the game's history. The act of visiting was, for some people, more like a pilgrimage or celebration.

The traditional pedagogical models that apply to the production of historic research are not appropriate for assessing the significance of this type of history. Whereas monographs or dissertations are judged on the excavation and interpretation of new archival material, social history exhibitions such as League of Legends perform a different function. They explore the popular memory of a community. The history is not so much revealed as enacted or performed. In the case of League of Legends, the exhibition validated the lived experience of people who played and watched the game. The motivation of visitors, as such, was one centred on memory rather than learning. When viewed in this fashion, League of Legends can be seen as a set of resources for visitors to construct their own historical narratives. Their memories were enabled by the material on display. This focus on celebration or memory became most apparent to me when observing visitors in the exhibition space. I saw discussions between fathers and sons, or grandfathers and grandchildren. The exhibition facilitated an intergenerational dialogue about the game's history. The photographs and objects provided visual cues for visitors to compare and contrast their memories. It was an opportunity for an older generation to tell stories to the young.

League of Legends provided a great opportunity for fans to see some of the treasures of Australian rugby league and review its history. From a difficult birth at the beginning of the twentieth century, rugby league grew to assume a central place in Australian life at the start of the twenty-first century. The past 100 years revealed a great drive for adaptation and change reflected in changing rules, the move from an amateur to a professional code, and the development of the game as a form of mass sports entertainment. For me, the lesson of the game's history is that rugby league provides a field on which our most elemental emotions find expression. There is pride in community, ecstasy in victory and despair at defeat. There is also aggression and ambition as well as sacrifice and courage. Next time you visit a leagues club with the sound of distant poker machines and the restaurant public address system — 'Number 10, your schnitzel is ready' — pause for a moment and take a look at the trophy cabinet. There is history there.

1 John Carroll (chairman), Review of the National Museum of Australia — Its Exhibitions and Programs, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2003, p. 29.2 Marion Stell, Exhibition review, 'Between the flags: 100 years of surf lifesaving', reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 2, no. 1, March 2007, www.recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_2_no_1.3 Other curators who worked on the exhibition were Adrian Henham, Aaron Pegram and Cinnamon van Reyk. Image research for the exhibition was undertaken by rugby league historian Terry Williams. Journalist and historian Ian Heads was contracted as an adviser and fact checker. The project manager was Mark Wright. Exhibition design was undertaken by Acumen Design.4 The objects featured in League of Legends were drawn from the Museum's collection, the collections of the New South Wales, Queensland and Australian rugby leagues, suburban and regional clubs and individual collectors. A full object list is available in the exhibition catalogue, League of Legends: 100 Years of Rugby League in Australia, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2008, pp. 93–100. Many of the objects can also be seen on the website created for the exhibition, www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/league_of_legends. 5 See 'Footy yarns', www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/league_of_legends/share_your_story.6 National Museum of Australia exhibition attendance figures.7League of Legends visitor survey, results of 50 exit interviews, March and April 2008, National Museum of Australia internal report.8 ibid., p. 5.9 ibid.10 ibid.11 ibid.12 Visitor statistics/audience research report, National Museum of Australia, May 2008, p. 12.13 Visitor feedback form, September 2008.