In 1973 antiques dealer John Hawkins heard a story about a 'box of stuffed birds'. The box was held in the junk room of Strathellan Castle in the Scottish Highlands and, from what Hawkins heard, it was a collectors' chest from Australia dating back to the early nineteenth century that was full of a variety of curiosities from the natural world. Earlier, the chest had failed to fetch the reserve price of £1000 at auction. Hawkins offered the reserve but was declined. Five years later he travelled to Strathellan Castle to view the chest himself. When he saw it, he recalled having seen a similar chest, held in the Mitchell Library collection at the State Library of New South Wales, where it was known as the Dixon chest. Hawkins offered £5000 but the owner declined. A few years later Hawkins offered £100,000 and again it was declined. In 1989, at a Sotheby's auction in Melbourne the chest sold for one of the highest prices paid for a decorative arts object at an Australian auction. The hammer hit at $583,000.

After auction the chest was in private ownership for 16 years until it was sold to the Mitchell Library in 2004. Its authenticity was confirmed by librarians and it became known as the Macquarie collectors' chest. The chest is assumed to be part of the personal collection of Lachlan Macquarie, the fifth governor of New South Wales, and he took it back to Scotland in 1822 after leaving the colony. It has few known equivalents.

In Rare & Curious: The Secret History of Governor Macquarie's Collectors' Chest, Elizabeth Ellis sets out to solve some of the puzzles associated with this remarkable object. The chest is an extraordinary collection of Australian nature from the turn of the nineteenth century. Ellis describes it as 'a museum in miniature, a celebration of friendship and patronage, and a joyous expression of very personal appreciation of the glories of the natural world of Australia in the initial flush of enthusiasm in the decades following white settlement' (p. 3). The extraordinary effort that went into creating the chest must surely capture the imagination of any modern day collector.

Opening the cedar case from the top the viewer is presented with a panel of painted fish, and two side panels of Newcastle landscapes. Folding out the top layer there are two cases of butterflies and beneath are collections of beetles and insects. Further below there are four trays of birds. The middle drawers pull out to contain shells; and hidden side drawers contain other marine specimens, mostly seaweeds and sponges. Then there is the artwork on the panels as they lift out to reveal the different drawers of natural curiosities. The artwork is primarily of colonial Newcastle and surrounds and is most likely from the Newcastle academy of painters that was formed by Captain James Wallis, commander of Newcastle at the time and a keen artist. The convict artist Joseph Lycett is presumed to be the primary creator of the artworks.

Describing the chest as a 'Chinese puzzle in which every part is interrelated', Ellis suggests that it must have taken years to compile because 'if one small portion was not aligned, the whole would not work' (p. 145). From red cedar to polish, from birds to the Newcastle academy, the stories bursting from the chest take Rare & Curious on a journey to describe the history of the chest in great detail. There are also significant discussions of Sydney town and Macquarie's vision, and his relationship with Wallis, whom Macquarie had appointed. Wallis appears to have had the chest built as a gift to Macquarie.

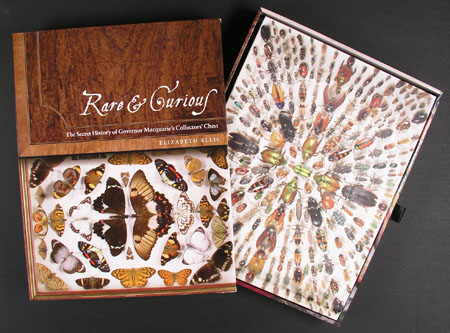

The chest was intended to provide 'private entertainment in genteel 1820s drawing rooms or libraries where a few select guests would exclaim with surprise and delight as the hidden layers of contents were gradually revealed' (p. 12). This notion has inspired the publication of Rare & Curious. The book is as lavish as the efforts of the compilers of the chest. It comes in a glossy illustrated cardboard case with a drawer that pulls out to reveal the book. The covers of the book are illustrated with pictures of the insect collections, and inside, the numerous illustrations of the entire chest take you close to the object. Mimicking the chest through the physicality of the book evokes the historical context of the object's creation and invites consideration of its aesthetic beauty.

From a curatorial perspective, at times the book almost feels like an extended object report: the prose is sometimes quaint and the discussions of Macquarie, particularly the Commission of Inquiry into his administration, are overly sympathetic to the governor. But at each turn, through both storytelling and the lavishness of many of the illustrations, the wonder and delight of the chest is conveyed.

The notion of history as a 'detective hunt' and a 'puzzle' is a recurrent theme for Ellis. Whether or not one agrees, both the idea of assembling specimens of nature into beautiful chests of curiosities and the circumstantial evidence relating to Macquarie's ownership does show how histories inspired by nature and objects tell multi-layered stories within a single narrative. 'The bottom drawer', a delightful closing chapter, makes this point with subtlety by unravelling much of Ellis's authority and hinting at many of the ambiguities still held within the object. These will continue to inspire collectors and historians.

The Macquarie collectors' chest is a compelling Australian object that has been brought to life in Rare & Curious. Its creation clearly influenced by aesthetic considerations, the chest displays a form of natural history that seems so out-dated, so entirely out of step with current scientific drive for objectivity and fact. In this sense Rare & Curious, and its commitment to recreating something of the aura of the original chest, deserves consideration by anyone interested in the early roots of natural history in Australia. But be warned, such magic might require a journey beyond the book: to the State Library of New South Wales to see the chest for yourself.