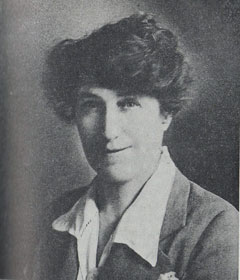

Cookbooks are a wonderful example of material culture — they have historic and social value that make them an important part of a museum collection. They provide a range of insights into everyday life such as attitudes towards food, domestic economy and the roles of women. This article focuses on one particular cookbook, an edition of which forms part of the National Museum of Australia's National Historical Collection. Our Cookery Book, written by Flora Pell and first published in Victoria in 1916, was reprinted more than 24 times until the 1950s. A study of the cookbook and the life of its author reveals much about the education of girls, the changing role of women in society, nutrition, nation-building and the power of the temperance movement in early twentieth-century Australia. Flora Pell was a living contradiction who espoused a woman's 'heaven-appointed mission' as a 'wife and homemaker' while forging a career for herself in the Victorian Education Department. Her recipes and 'valuable home hints' were in the press, on the airwaves and in print. She may well have been Australia's first celebrity chef. The authors, a curator and a historian, have tackled the subject from complementary perspectives and offer different interpretations of the cookbook as object and historical text. They conclude with an examination of how this seemingly innocuous, but highly controversial and influential cookbook can be interpreted for a museum audience.

photograph by Alison Wishart

National Museum of Australia

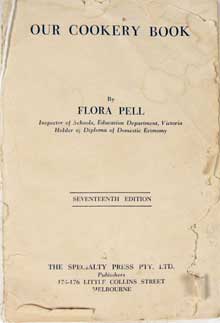

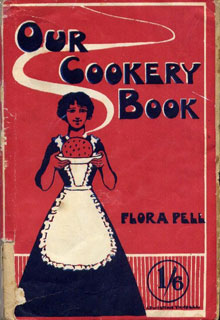

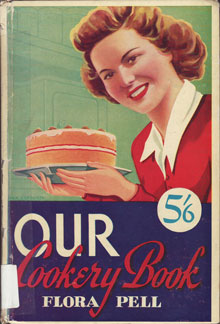

Our Cookery Book was reprinted at least 24 times from 1916 until the 1950s.[2] Any one of those copies could be used to consider the individual reader, who might be cook, daughter, mother, wife, student, almost certainly a woman. Unlike other forms of literature, most cookbooks are utilitarian and lay bare signs of their use and handling, the handwritten notes in the margins and personal recipes in the back, the worn pages, food stains and broken spines. Alternatively, a copy could be used to explore the theory and practice of foodmaking, including changes in approach between the 1st and the 24th edition. The National Museum's copy, the 17th edition, could be scrutinised to find out more about its provenance and publishing history. Our purposes here, though, are to focus on the author, Flora Pell, and to use the book as a window into the period and other women's lives.

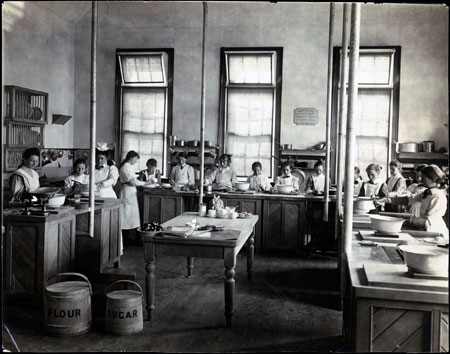

Flora Pell was born in Melbourne on 12 March 1874 and commenced work as a probationary teacher when she was 15 years old. She passed her teacher's exams and became an instructor in cookery at schools in the Victorian towns of Geelong and Bendigo and then in the Melbourne suburb of Carlton. This experience prepared her to organise the cookery section at the State Schools Exhibition in 1906 (Fig. 3). From the end of the nineteenth century, world fairs and colonial or state exhibitions were an important forum for popularising the new domestic science.[3] When Pell was appointed supervisor of cookery at the Melbourne Continuation School in 1908, her superiors stated that:

[Pell] has undertaken the training of the first cookery teachers. Exceedingly hard-working, capable, interested, reliable, enthusiastic, tactful. Miss Pell is a valuable public servant.[4]Pell continued to rise through the ranks of the Victorian Education Department, becoming headmistress of the Collingwood Domestic Arts School when it opened in 1915. While she was in charge of this school, she seized the opportunity presented by a meeting in Melbourne of all the state Education Department directors and organised for her cookery students to prepare and serve a four-course luncheon. The Victorian premier, Minister for Education, Director of Education, and mayor of Collingwood also tasted the students' achievements and were most impressed.[5] Pell knew that good cooking could win influential friends.

National Library of Australia

The domestic arts movement was actually a transnational one and, however isolated Australia may have seemed in a geographical sense, the movement was not removed from developments elsewhere. The United States as well as England provided inspiration and models, and the interplay between external influences and local experiences is apparent in Pell's own work. In 1923, she embarked on an 'extensive tour of America' to examine their domestic arts schools. She probably organised and funded the tour herself, as there is no information in the Education Department records to indicate otherwise. She concluded that, while the equipment and facilities in American colleges were 'magnificent', schools in Melbourne had 'nothing to learn' from them.[9] However, she did think that Australians would benefit from incorporating aspects of the American diet, which included salad with almost every meal, far less red meat and 'dainty' breakfasts of 'grapefruit or oranges and freshly made rolls and coffee'.[10] As she toured the United States, she gave lectures about cooking and Australia.

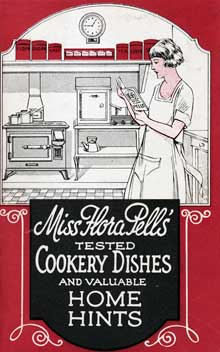

By 1925, Flora Pell's reputation had grown to the extent that her publishers thought it would be profitable to issue a book with her name in the title: Miss Flora Pell's Tested Cookery Dishes and Valuable Home Hints (Fig. 5). This created more demand for Pell and she soon found herself being invited to speak to women's, business and charity groups.[11] From 1925 to 1928, she had a regular spot on Melbourne's 3LO radio where she discussed cooking tips and domestic economy. Her ideas were often aired in the press, particularly by her friend Stella Allan, who used the pseudonym 'Vesta' to write the weekly 'Women to women' column in the Argus. Pell was on the airwaves, in print and in the papers. She may have been Australia's first celebrity chef.[12]

By 1916, when Our Cookery Book was first published, Pell had been teaching cooking in Victorian schools for nearly 25 years. She felt there was a need for a cookery textbook to replace the recipe cards that the students (all girls) invariably lost and to provide more recipes and information. Our Cookery Book became the informal cooking textbook and was used by mothers and daughters alike. The book stands as a significant historical resource because its purpose was to teach the general principles and techniques of contemporary cookery — the basic preparations for meals that were common at the time. But the book was also written to change the status of cooking and eating.

Flora Pell was one of the first Australian cookbook authors to talk about nutrition. She understood the importance of a balanced diet, declaring that 'The needs of the mind and body are served best by a diet in which the different elements are in proper proportion'.[13] In the introduction to Our Cookery Book, she identified the five components 'necessary to build up the body' and maintain it in a 'vigorous condition':

1. Body-builders (protein)

2. Heat-producers (fats)

3. Energy-producers (carbohydrates)

4. Water

5. Mineral Salts.[14]

Today nutritionists would also say that fibre and vitamins are vital to good health, but these were not 'discovered' until the late 1940s. Pell does discuss 'the vitamines' and identifies those foods containing vitamins A, B and C.[15]

Nutritionist Michelle Minehan, from the University of Canberra, has analysed Pell's discussion on nutrition and compared it to what we know today. Pell's recommendations for daily intake (for a man of moderate work) are within the current dietary guidelines.

Table 1: Comparison of Pell's quantitative recommendations for protein, fat and carbohydrate as % total energy intake with current standards

| % energy from nutrient | % energy from nutrient | |

| Flora Pell | NHMRC AMDR | |

| protein | 20 | 15–25 |

| fat | 20 | 20–35 |

| carbohydrate | 60 | 45–65 |

*NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) AMDR (Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range) is the range of macronutrient intakes on a % energy basis considered to reduce chronic disease risk while still ensuring adequate micronutrient status.

Writing in 1916, Pell commented that meat need only be consumed once a day instead of two or three, which was common practice in Australia at that time. She informed readers about the different cuts of meat for pork, beef, chicken and lamb, and provides recipes for using every part of the animal — tongue, liver, head, neck, knuckles, tail. The cheaper cuts of meat, she observed, provide an economical source of protein. Today, unfashionable parts of the slaughtered animal are turned into pet food and fertiliser, thereby increasing the environmental and financial cost of meat production. Knowledge of how to cook the cheaper cuts of meat has largely disappeared in modern society. Pell also identified alternative sources of protein such as split peas, eggs, nuts, oatmeal and milk and advocates a varied diet.[16] Today's nutritionists would add fish to this list.

Fats were harder to obtain and much more expensive when Pell was writing. Nevertheless, she recognised the protective quality of fats and believed that children 'must not be stinted of them'. Nutritionists today can identify different types of fat: saturated fat, omega-3 fatty acids, polyunsaturated fats, and so on. Most of Pell's recipes use saturated fats such as dripping, suet and butter which are less healthy than fats derived from plants such as olive oil and avocado. Perhaps this explains why Pell's suggested daily intake of fats is at the lower end of the current recommended range (see Table 1).

Pell regarded carbohydrates as 'energy-producers', which is still how they are understood today. She identified treacle as the cheapest source of carbohydrate. Today there are many processed and refined sugars and starches available and having a sufficient carbohydrate intake is not a problem for most Australians.

A close reading of Pell's discussion of 'Facts about food' implies that many Australians suffered from under-nutrition. She sought to educate them about the importance of different nutrients, where to find them in food and how to get the balance right.

While Flora Pell's knowledge of nutrition was not comprehensive, she was better informed than many of her contemporaries. She believed that 'a cook should possess the information of the relative proportion of the food elements [nutrients] in each dish, and so place the meal that there will be harmony in the food from first to last'. Maintaining a good diet was not only healthy, it was also thrifty and godly: 'Simplicity in diet and preparation makes living less expensive, prevents disease, promotes health, and makes one more susceptible to truth, and enables the individual to render more acceptable service to God'.[17] Pell also provided information about 'economy in the provision of food' and 'utilising left-overs'. This implies that feeding a family healthy food was an expensive operation in 1916, as it is today. Readers learn how to cook tough cuts of meat, and use celery tops, stale bread, sour milk, bacon rind and leftover vegetables in cooking.[18] Modern Australians could learn much from Pell's strategies to economise and minimise food wastage.

Pell used her cookbook and her classroom to equip young girls — future mothers — for their role as 'nation builders'. Through her cookbooks and her teaching, Pell espoused a contemporary expression of patriotism. Food is one of the strategies through which 'imagined communities' are given identity by organising a sense of belonging to a particular geographical location, but she is less concerned with a unique national food than the importance of food in nation-building. Pell believed that nation-building starts in the kitchen. As she wrote in 1906: 'the teaching of domestic economy is to be the power that makes the happy home, and the happy home means a prosperous nation, because, from the home, we must recruit our citizens'.[19] Our Cookery Book was first published in 1916, during the depths of the First World War. The war generated expressions of loyalty in a range of cultural spheres, although emphasis was placed on ties to the 'mother country' as well as the nation. The war period in Australia was characterised by a strengthening of claims to a common British heritage and loyalty to the Empire. With a rolling pin and a knowledge of nutrition, Pell was teaching women to raise up an army.

A close examination of photographs of contemporary cookery classrooms adds to this thesis. Figure 3 shows a cookery demonstration at the Melbourne State Schools exhibition in 1906. Figure 6 shows a classroom at the Melbourne Continuation School, where Pell taught in 1906. Australian flags festooned above the girls' heads are conspicuous. Flags and other symbols of patriotism are noticeably lacking in classrooms where science and maths were taught or where boys learnt sloyd. Pell realised that 'the housekeeper is in a position to wield a tremendous influence on the mind and body, hence upon the family, society, and the nation'.[20]

Attachment to the nation and aspirations to citizenship did not supersede Flora Pell's commitment to family. Indeed, the motherhood principle had provided strong arguments for the right to vote and participate in public affairs. Pell herself didn't marry until 1935, when she was 60 years old, defying her own commitment to a woman's 'heaven-appointed mission'.[23] It is uncertain whether she chose a career over marriage, though given her attitudes towards the importance of motherhood and a woman's duty, this is unlikely. Family circumstances meant that she was the breadwinner, as her father remarried following the death of her mother and had four more children before he died in 1893. It is probable that as the only surviving child from her father's first marriage, Pell was actively involved in caring and providing for her four step-siblings. Their mother, Charlotte (née Jeffreson), did not remarry.[24]

Support for formal domestic training for girls came from women's organisations such as the National Council for Women, suffrage groups and wealthy upper-class families. For example, businessman and politician Sir William McPherson provided £25,000 for the building of a new domestic science college[27] in Melbourne which was named after his wife Emily and opened in 1926 (Fig. 8). The motivation of upper-class supporters was not purely philanthropic, as they hoped that girls trained in domestic science might choose to become their domestic servants and stem the flow of girls into factory and shop work. They also felt that working-class girls needed to learn 'upper-class' values of order, propriety, hygiene and household management.[28]

In 1915, the Victorian Education Department responded to the public pressure for more domestic training for girls and established two domestic arts colleges, one in Bell Street, Fitzroy, and the other in Collingwood. The Collingwood school was established in Vere Street in a building remodelled at a cost of £1960, a considerable investment (Fig. 9).[29]

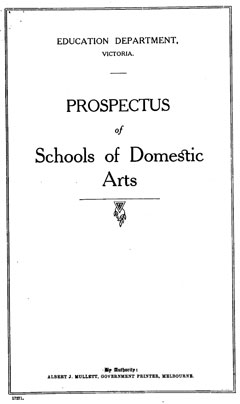

Domestic arts colleges were specialised high schools just for girls. Girls aged 12–14 years spent half the week learning cookery, laundry work, needlework, millinery, dressmaking, personal and domestic hygiene and practical household management. For the other half of the week, they received instruction in academic subjects: English, arithmetic, science, history, and so on.[30] A domestic arts course which provided 'systematic and comprehensive training that should enable them [students] to become efficient homekeepers' was regarded by the Education Department as far more relevant for girls than ordinary secondary school, as they were likely to marry, which in the 1920s meant forfeiting one's place in the paid workforce.[31]

Although no fees were charged to the daytime students, teachers were also required to offer evening classes to 'working girls' for a small fee. The Education Department retained this revenue to help offset the high cost of establishing, equipping and running the centres. Domestic arts teachers like Flora Pell not only had to teach the day and evening students how to cook, but also how to minimise wastage of food and fuel.[32] Meals cooked at the college were sold cheaply to workers in the surrounding areas, which helped to recoup the cost of the ingredients.[33]

courtesy John Young

The initial experiment with domestic arts colleges must have proved successful as by 1931 there were 12 colleges in Victoria: 10 in metropolitan Melbourne, and one each in Ballarat and Bendigo. The larger colleges had a demonstration flat and kitchen — a sort of model house occupied by two teachers — in addition to the cooking rooms.[34] As Inspectress of Domestic Arts from 1924, Pell was ultimately responsible for their operation.

Pell was passionate about her job. She firmly believed that a girl's education was incomplete if she hadn't been trained in the principles of 'true household economy', cookery and nutrition. These three things are covered in detail in Our Cookery Book and Pell's two other cookbooks.[35] For Pell, girls were 'the guardians of the future'. She believed there was a link between training girls to be wise mothers who ran efficient and effective households and cared for the physical, mental and moral health of their children, and the prevention of juvenile crime.[36] Women might be allowed to work outside the home in a limited range of occupations, but their most important work would take place in the home. At this time Pell was not a wife or mother herself, but she was a proponent of 'domestic feminism' and upheld socially conservative gender roles.

Domestic arts schools or colleges could serve the national good and individual aspirations, but these were clearly shaped by both gender and class. Flora Pell and her supporters saw the provision of domestic arts colleges as the answer to the problem of 'the fifteenth year'. In Victoria in the 1920s, girls and boys finished school in their 14th year, but girls were not allowed to start work in factories until they were 15 years old. Pell believed that many girls drifted, with no routine, purpose or discipline in their lives and that 'no one ever drifts forward: the drift is always backwards'.[37] The locations of the new centres established during the 1920s, which Pell oversaw, were in industrial suburbs where girls' educations were likely to finish at 14. At the same time that Pell was espousing the moral benefits of a continuing education, community leaders in Melbourne were concerned about the return of soldiers with venereal diseases from the First World War who drifted in and out of employment. Fearing that these young girls and returned soldiers would drift towards each other, they thought that programs for training girls in the principles and practices of motherhood could assist in the control of the spread of venereal disease.[38] To prevent young girls from developing lazy, and possibly even immoral habits, Pell advocated that girls should be kept under the control of the Education Department and made to attend domestic arts centres, for at least a couple of days a week.[39] However, as secondary education grew in the inter-war years, girls increasingly chose to take up academic rather than domestic arts/science courses in senior years.[40]

Critics of teaching domestic arts argued that cooking was something girls could and should learn at home from their mothers and was a waste of time and money in schools. Mothers who supported this view wanted their daughters at home to help them, and resented that they were learning to scrub tables and clean stoves in school kitchens. Some girls preferred to take more vocationally useful subjects like short-hand and typing or academic subjects.[41] Indeed, if cooking and food preparation was such a natural and fulfilling activity for women, the teaching of domestic science was redundant. Pell's books can be read then, not just as evidence of contemporary attitudes about women's role and the security of domestic ideology, but only as an articulation of uncertainty about these norms and anxiety about their endurance.

Our Cookery Book was a source of great pride for its author. Its popularity and Pell's reputation as an excellent cookery supervisor led in 1926 to the Victorian State Dried Fruits Board asking her to compile a recipe book with 50 recipes containing only dried fruits (Fig.11). Through her employment and royalties, she gained financial independence. However, Our Cookery Book also encountered opposition, causing its author great distress and leading to her premature retirement in 1929.

The genesis of Our Cookery Book was Pell's extensive experience as a cookery teacher in Victorian schools. The Education Department required cookery students to purchase a set of 30 recipe cards for a shilling per set, with replacement cards costing a penny each.[42] Pell saw the need for a cookery book with more recipes and information about nutrition, cuts of meat, economising with food and leftovers, cooking for invalids and general cooking tips. She wrote her cookbook, found a publisher and in 1915 wrote to Frank Tate, director of the Education Department, seeking his permission to bring out a book to replace the recipe cards.[43] When Tate replied that he did not want students to have to purchase a book, Pell was undeterred. Our Cookery Book was published by George Robertson and Co. in 1916 and at a retail price of 1s.6d. was quickly taken up by cookery teachers and students.

This cookbook was distributed free of charge to encourage Australians to eat more dried fruits. Australians were only consuming about one-third of the fruit produced, much of which was grown by returned soldiers.

Newspaper publicity for the cookbook proclaimed: 'this book is the new text-book for all cookery pupils in the Government high schools and must be in the possession of all'.[44] The Education Department responded with a strongly worded letter asking her on whose authority she was issuing a textbook. She replied that she had worked on the cookbook in her own time, did not authorise the use of the words 'text-book' in the advertising and then went on the offensive, quoting an independent reviewer in the Argus: 'It is doubtful whether any cookery book has yet been issued which would make the work as easy as this does for young housekeepers'.[45] The department held its ground, telling Pell that Our Cookery Book was not approved by the minister and could not be recognised as a textbook.

It is unclear whether Pell actively encouraged the use of her cookbook in schools or neglected to discourage it, but Our Cookery Book gradually replaced the recipe cards. Its use might have gone unnoticed by the department, were it not for the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). In 1926, 10 years after Our Cookery Book was first published, the Victorian branch wrote to the Director of Education, concerned that schoolchildren were being taught to make trifle using sherry. The director asked Pell if any such recipes were in use in schools and she replied that wine was not used in any recipes which were taught in cookery classes. Technically, this was true, as the recipes in Pell's book which do contain alcohol, 'namely rich fruit cakes and pudding with a little brandy which enables the sauce to be kept for a length of time ... take five hours to cook without allowing time to prepare so can not well be included in a day's cookery practice'.[46] However, this was not good enough for the WCTU who wrote to the director again in 1928, urging him to make good his 'definite promise' made at a conference held at Bell Street Domestic Arts College in the previous year to remove the cookbook, 'which includes intoxicating liquor in recipes'. Pell's popular cookbook had embarrassed her employer. When asked to explain, she promised to make arrangements with her publisher to have all the offending recipes removed from subsequent editions.[47]

There was more trouble to come. Having been told by the WCTU that Our Cookery Book was still being used in schools, the new Director of Education, NP Hansen, asked how the book had come to supplant the recipe cards, and whether Pell had the right to receive royalties for a book that was published using her departmental title, 'Supervisor of Cookery, Education Department and Headmistress, Domestic Arts School' and, later, 'Inspectress of Schools'. The department was annoyed that 1900 sets of its recipe cards were sitting unused and unsold at the Government Printing Office, while Pell and her publisher were reaping rewards. Pell was called before the director and two senior officials in the Education Department and informed of the 'undesirability of officers being interested financially in books of which they could officially influence the use, and advised to apply for permission to accept royalties'.[48]

The current publisher, Specialty Press, feared that this profitable cookbook, now in its 11th edition, might be banned, and wrote to the department requesting permission to continue to publish it with no recipes containing alcohol and no advertisements. On receipt of a proof copy for approval, the department forwarded it to Miss RS Chisholm, headmistress of the Emily McPherson College of Domestic Economy, seeking her opinion on the suitability of Our Cookery Book as a text. One month later Miss Chisholm submitted her confidential report. She cattishly stated in her cover letter: 'if I had not been selected for this post [of headmistress] I should probably have asked for your cooperation in some such scheme, as it is I am the more qualified to do it'. She planted a seed in the director's mind by suggesting that the cookbook could be rewritten and expanded to include general household hints 'by a little group of whom I could be one'. Nevertheless, she gave the book grudging approval. In the body of her four-page report, she admitted that 'I have myself taught from it in domestic arts schools and cookery schools and used it in home cookery and sold many copies'. She concluded that 'until a better text book is written, or this is revised as indicated, Our Cookery Book is a fairly suitable text for girls of 12–15'.[49]

Based on this advice, the Director of Education recommended that Our Cookery Book be used as a school text, provided that it include no advertisements or recipes containing alcohol. He had already received the government's permission for Pell to receive royalties, although this was never communicated to Pell. However, with an evident eye to economy, the Minister for Education chose to go against the advice of his director and Miss Chisholm's confidential report, and ordered that schools revert to using recipe cards (which they had not used for 13 years) until all the remaining 1900 sets of cards had been distributed. In the meantime, a committee of experts, including Miss Pell and Miss Chisholm, was to write a new textbook on 'cookery, laundry and dietetics, and housewifery' that the department would publish. Estimates presented to the minister, based on the current retail price of 1s.6d. and a demand for 10,000 books per annum, showed that the department would make a profit of £311 5s.6d. each year.[50]

Pell was outraged by this proposal, telling the director that it would be a retrograde step to use the cookery cards that were printed 27 years ago. She was so keen that Our Cookery Book remain in schools that she was prepared to forgo some of her profits, writing that 'if it is a matter of royalties, perhaps some arrangement could be made'. She told the director that Our Cookery Book was used by students in Tasmania and that exchange teachers visiting from London and Leicester purchased extra copies to take home for use in their schools. She insisted that there was no need for another book, such as the one proposed by the department.

Pell's letter was acknowledged but ignored. So too was a letter from Miss Grace McLaren, headmistress of the domestic arts college at Geelong and a friend of Pell's, who wrote on behalf of all headmistresses of domestic arts colleges urging the continued use of Our Cookery Book.[51] The department proceeded to appoint two authors of a new domestic arts textbook and asked Pell to work on the cookery chapters with another cookery supervisor.[52] Sometime in the next week, she commenced three months' sick leave.

If Pell, the author of three successful cookery books, felt humiliated by the department's proposal that she should contribute to the co-authored work, she did not show it. When asked by the departmental secretary if she would be able to write her section of the new textbook, she replied that she had continued to work while on leave and that she would finish her section of the book before the new school year commenced in 1929.[53]

Returning to work, Pell learnt that Grace McLaren had continued to lobby on her behalf. She had sent a circular to all the cookery centres and domestic arts colleges in Victoria urging 'that the use of "Our Cookery Book" be continued in our Cookery Schools'. Senior staff were asked to sign the circular, add their own comments and send it back to McLaren. One circular was signed by Miss Keiller, Pell's co-author of the cookery section in the proposed new textbook. A change of government towards the end of 1928, including the appointment of a new Minister for Public Instruction, gave Pell an opportunity to restate her case. Seizing the moment, she wrote to the Director of Education, enclosing the circulars and 'respectfully and strongly requesting' the continued use of Our Cookery Book in schools, now that all recipes containing alcohol and all advertisements had been excised.

Pell's campaign backfired. The director accepted the advice of his senior officers to adhere to the decision of the former minister and called Pell in for an interview. The typed notes of the meeting record that Pell defended herself admirably. She denied any prior knowledge of Grace McLaren's actions in sending out the circulars, which had been interpreted as undermining the department's authority. Pell was again reprimanded for allowing Our Cookery Book to be used in schools and accepting royalties without the department's permission, and was instructed to continue working on the new textbook.

Pell obediently worked with her co-authors and submitted her section of the manuscript for the new textbook within the agreed timeframe. But the proposed textbook was never published. Early in 1929 she arranged for the distribution of the remaining 1900 sets of cookery cards to the 10 metropolitan domestic arts colleges, at the bargain price recommended by the department of sixpence per set. Ironically, or perhaps mischievously, two headmistresses wrote back to the department to say that they could not purchase their allocation of cookery cards as the students had already purchased Our Cookery Book.[54] On 8 November 1929 Pell retired from teaching owing to ill-health.[55] Her friends organised a party in her honour at the Berkeley tea rooms in Little Collins Street to 'give friends of Miss Pell an opportunity to meet her'.[56] It is amazing to think that a seemingly innocuous cookbook could cause so much trouble and lead to the downfall of a competent and highly regarded teacher and administrator.

When Flora Pell was promoted to Inspectress of Domestic Arts in 1924, the Argus reported that 'probably no woman has had greater influence than her on the promotion of domestic happiness among the younger generation in Victoria'.[57] Young girls' limited opportunities to learn the domestic arts provided a strong argument for their place in the curriculum and the elevation of the home as a 'dignified activity of national importance'. Beyond being a blueprint for meals, Our Cookery Book contributed to much broader debates about the role of women and the new citizen nation which they participated in. Its removal as a school textbook attests to the significance of the temperance movement and exposes the cookbook as a contested terrain that could also be read in terms of anxieties over gender roles and the contradictions of domestic science. As a form of popular culture the book was appropriated to different ends and could be used to recontextualise the meanings of any of these — national loyalties, the role of women, the citizen subject, education, nutrition, individual ambition and work/life balance.

It is planned to include Flora Pell's story in the National Museum of Australia's Eternity gallery (a biographical based gallery that tells the stories of 50 ordinary and extraordinary Australians) from October 2010.[58] One of the challenges for curators is how to communicate the significance of Flora Pell's contributions. How do you communicate the turbulent history of a popular and apparently harmless cookbook? We have used over 5000 words to discuss Pell's publications, teaching career and philosophies about women, education, cooking, nutrition and patriotism, but in an exhibition context, a curator might have only an object label of about 30 words and a theme panel of approximately 150 words to work with.[59] Distilling the essence of an object and its creator and the multiple layers of meaning into so few words is extremely difficult, if not impossible.

In an exhibition context, the curator is trying to establish a dialogue or a relationship between the visitor and the object — or, to use a discourse analysis framework, between the signifier (the object) and the receiver (the visitor). The word 'receiver' is problematic as it implies that the communication is one-way: from the object to the visitor/receiver. As Susan Pearce notes, 'meaning develops as an interactive process between thing and viewer' — it is two-way communication.[60] The object should trigger thoughts or memories for the viewer that allow them to connect with their own experiences and bring those experiences to the interpretive process. No matter what meaning curators try to impose on an object, visitors will work from their existing bank of knowledge and experience. That's why one of the principles of interpretation is to make a personal connection with and be relevant to the experiences of the visitors.[61]

Ian Hodder believes there are three layers of meaning embedded in objects: functional, symbolic and historical.[62] This can be a useful framework for organising the complex significance of an object and thinking through how best to communicate this.

Applying Hodder's framework to Flora Pell in general, and Our Cookery Book in particular, the functional significance is that this is a cookbook. It contains recipes, information about nutrition and how to make economical use of leftovers, and tips for choosing the best ingredients and the best cuts of meat.

photograph by Alison Wishart

We suspect that visitors from the baby-boomer generation and anyone who has a cursory knowledge of the ethos of the 1950s will, when they see the cover of the 24th edition (Fig. 13), think of white picket fences, white goods and women in pearls and twin-sets standing in front of a new Frigidaire. This is a lot of stereotypes for a curator to overcome, in order to communicate the historical significance of the object. Even though Our Cookery Book was published in 24 editions and is Pell's best-known publication, it only seems to have been published with two different cover illustrations. There are very few copies available in good condition. The National Museum's copy (the 17th edition) is especially unhelpful: it has lost its cover!

Of course it is unrealistic and unreasonable to expect one object to do all the interpretive work. There are many stories associated with Our Cookery Book and one book cover can not tell them all. Including images of the flags festooned above the girls' heads in the cookery classrooms (see Figs 3 and 6); a copy of the letterhead of the Women's Christian Temperance Union; photographs of Miss Pell (see Figs 2 and 14); a copy of the prospectus for the Domestic Arts Colleges (see Fig. 7); copies of the covers of her other cookbooks (see Figs 5 and 11) and cooking equipment used around 1916 will help to communicate the significance of Flora Pell.

Content layering is a way of adding information, and is a common interpretive practice in exhibitions. Curators recognise that not every visitor wants to delve too deeply into a story. Content can be provided in layers that become more informative, conceptual and intellectual, the further you 'dig'.[63] The opportunity to incorporate a short film in the Eternity gallery display provides scope to convey some of the drama of Flora Pell's career, and the significance of her work.

Sometimes it helps to extend the interpretive toolkit beyond text, images and objects. This is a recipe book. It is about cooking and eating. Visitors viewing this object would probably like to look at the recipes it contains. The book needs to be displayed in a sealed case for its own protection, but given that the recipes are no longer in copyright, it is possible to reproduce some of them for visitors to take away — perhaps on attractive postcards with a copy of the cover illustration of Our Cookery Book on the front and a recipe and some information about the book on the back. This was a technique employed by the State Library of New South Wales to promote their display of Australian cookbooks in 2009. Some recipes could be added to the exhibition website for visitors to download. Web users could be asked to comment on how the recipe turned out for them and to post their comments to the site.[64]

Perhaps the museum café could cook some of Pell's dishes and offer them for sale to visitors. Being able to purchase at the café a piece of Pell's Belgium pound cake, clearly labelled as such, would provide a tasty and memorable link for visitors.[65] It would also help to bring Our Cookery Book alive.

Museums care for objects and store knowledge. They collect as well as display; but they also have the opportunity to gather new knowledge and their objects have the capacity to offer new interpretations. Pell offers readers two things simultaneously: a self-image that fitted a fairly traditional female role of nurturer and homemaker, and an opportunity to embrace a new and less familiar civic role. Within a national framework it is possible to cast Pell's life in the context of federation and nationhood, the experiences of the First World War and the new citizen nation growing out of that. Her generation experienced compulsory schooling, represented as a means of encouraging self-regulation and service in terms of work and the nation. Cookbooks offer an abundance of meanings and readings. They are both texts and objects — blueprints for meals, interventions in the diet of the nation and debates about food and home. These are issues that continue to command attention in our contemporary preoccupation with what to eat for dinner.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

1 Anne L Bower, 'Romanced by cookbooks', Gastronomica — The Journal of Food and Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, Spring 2004, 35–42; Jessamyn Neuhaus, 'The way to a man's heart: Gender roles, domestic ideology, and cookbooks in the 1950s', Journal of Social History, vol. 32, 1999, 529–55; Janet Theophano, Eat My Words: Reading Women's Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2002; Rosalind Coward, Female Desire: Women's Sexuality Today, Paladin, London, 1984; Jean Duruz, 'Food as nostalgia: Eating the fifties and sixties', Australian Historical Studies, vol. 30, no. 113, October 1999, 231–50; Janet Floyd & Laurel Forster, 'The recipe in its cultural contexts', in Janet Floyd & Laurel Forster (eds), The Recipe Reader: Narratives — Contexts — Traditions, Ashgate, Aldershot, 2003, 1–2.

2 John Young, The School on the Flat: Collingwood College 1882–2007, Collingwood College, Melbourne, 2007, p. 29. The most recent edition we have seen is the 24th, which, judging by the cover illustration, was published in the 1950s. If anyone is aware of a later edition, please contact the authors.

3 The Centennial Exhibition in Melbourne in 1888, for example, provided the occasion for the publication of a small book, later used by students of the author: Margaret J Pearson, Cookery Recipes for the People, H. Hearne, Melbourne, 1893 (3rd edn.).

4 PROV Teacher Record Card 11684.

5 Argus, 7 June 1918, p. 8.

6 Specialist subjects like cookery and sloyd were sometimes taught in the same centre with the girls using the room for two to three days and the boys for the other days in the week, depending on their numbers. The room was designed with extra cupboards for storing tools and cooking utensils and so that boards could be fitted to sloyd benches to make cookery tables. Pell, 'Report of Miss Flora Pell, Supervisor of Cookery', in Report of the Minister of Public Instruction, 1912, Appendix E, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, p.104.

7 Pell, 'Report of the Supervisor of Cookery', in Report of the Minister for Public Instruction, 1913–14, Appendix L, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, p. 80.

8 PROV Teacher Record Card 11684.

9 Argus, 17 November 1923, p. 21.

10 ibid.

11 Argus, 22 March 1927, p. 14 and 15 November 1928, p. 15.

12 The authors have not found any firm evidence of Flora Pell's popularity outside of Victoria but would like to talk to anyone from other states who may have used her book.

13 Flora Pell, Miss Flora Pell's Tested Cookery Dishes and Valuable Home Hints, Specialty Press, Melbourne, 1925, p. 6.

14 Flora Pell, Our Cookery Book, Specialty Press, Melbourne, 24th edition [1950], p. 5.

15 ibid., p. 9.

16 ibid., p. 7.

17 Pell, Miss Flora Pell's Tested Cookery Dishes, p. 5.

18 ibid., p. 10.

19 Flora Pell, 'Cookery', in Charles R Long (ed.), Record and Review of the State Schools Exhibition, September 1906, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1908, p. 69.

20 Pell, Miss Flora Pell's Tested Cookery Dishes, p. 5.

21 Pell, 'Cookery', p. 69.

22 Pell, 'Report of the Supervisor of Cookery', p. 80.

23 Flora Pell's marriage to John Chenoweth on 2 January 1935 was published in the Argus on 20 February 1935, p. 1.

24 Federation Index, Victoria 1889–1901; Edwardian Index, Victoria 1901–1913; Great War Index, Victoria, 1914–1918, Death Index Victoria, 1921–1985.

25 Argus, 2 August 1916, pp. 12, 13.

26 Argus, 11 October 1922, p. 4.

27 The terms 'domestic arts' and 'domestic science' were used interchangeably in the 1920s. Nowadays the most common term is 'domestic science'.

28 Kerreen Reiger, Disenchantment of the Home: Modernizing the Australian Family, 1880–1940, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985, p. 61.

29 The school is now the site of the Collingwood College, well known as the pioneer school for the Stephanie Alexander 'Kitchen garden program', engaging girls and boys in growing and cooking food.

30 PROV VPRS 10274/PO/2 File 1175, Prospectus of Schools of Domestic Arts [1917].

31 PROV VPRS 3854/PO/1.

32 Beverley Kingston, 'When did we teach our girls to cook?', Australian Cultural History: Food, Diet, Pleasure, 1996, no. 15, 1996, p. 95.

33 PROV VPRS 3854/PO/1.

34 John Young, The School on the Flat, p. 33.

35 Flora Pell also wrote Miss Flora Pell's Tested Cookery Dishes and Valuable Home Hints, published by Specialty Press in 1925 and A Sunshine Cookery Book

with 50 Dried Fruit Recipes for the Modern Table, published by the Victorian State Dried Fruits Board in about 1926.

36 'Vesta', 'Training of girls', Argus, 4 June 1924, p. 6.

37 ibid.

38 Judith Smart, 'The Great War and the "Scarlet Scourge": Debates about venereal diseases in Melbourne during World War I', in Judith Smart & Tony Wood (eds), ANZAC Muster: War and Society in Australia and New Zealand, 1914–1918 and 1939–1945, Monash University Publications in History, no. 14, 1992, p. 69.

39 Pell quoted in 'Vesta', 'Training of girls'.

40 Reiger, Disenchantment of the Home, p. 63.

41 Kingston, 'When did we teach our girls to cook?', pp. 98–9.

42 PROV VPRS 892/PO/105/1213, letter from Pell dated 5/9/1928.

43 ibid., letter from Pell dated 20/12/1915.

44

Argus, 8 July 1916, p. 6. Additional publicity was in the Argus on 16 July 1916 and the Herald on 11 July 1916.

45 PROV VPRS 892/PO/105/1213, letter from Pell dated 28/7/1916 and Argus, 16 July 1916.

46 ibid., letter from WCTU dated 24/8/1926 and letter from Pell dated 24/8/1926.

47 ibid., letter from WCTU dated 21/5/1928 and memo from Pell dated 24/5/1928.

48 ibid., departmental file note dated 14/7/1928.

49 ibid., confidential report submitted 10 August 1928 (emphasis in original).

50 ibid., departmental memo dated 5/9/1928.

51 ibid., departmental memo dated 10/10/1928 and letter from Miss McLaren dated 15/10/1928 and memo dated 17/10/1928.

52 ibid., departmental memo dated 10/10/1928 and 29/10/1928.

53 ibid., correspondence dated 30/11/1918 and from Pell dated 10/12/1928.The departmental secretary worked for the Director of Education.

54 ibid., memo from Miss Flynn dated 18/2/1929, correspondence from Pell dated 19/2/1929, from Richmond Domestic Arts School dated 11/2/1929 and Fitzroy Domestic Arts School dated 21/2/1929.

55 PROV Teacher Record Card 11684.

56 The party is advertised in the Argus, 17 March 1930, p. 17.

57

Argus, 31 May 1924, p. 20.

58 This gallery has a strict curatorial framework governing the consistent display and interpretation of the stories and their associated objects. See www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/now_showing/eternity.

59 These word limits are those recommended by the National Museum of Australia.

60 Susan Pearce, 'Objects as meaning; or narrating the past', in Susan M Pearce (ed.), Interpreting Objects and Collections, Leicester Readers in Museum Studies, Routledge, London and New York, 1994, p. 19.

61 Gianna Moscardo, Roy Ballantyne & Karen Hughes, Designing Interpretive Signs: Principles in Practice, Fulcrum Publishing, Colorado, 2007, p. 5, and Freeman Tilden, Interpreting Our Heritage, 3rd edn., University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1977, p. 9.

62 Ian Hodder, 'The contextual analysis of symbolic meanings', in Pearce (ed.), Interpreting Objects and Collections, p. 12.

63 This is well illustrated by the National Museum of Australia's Australian Journeys gallery, where content is provided at the object/label level (what the visitor first sees in the display case), contextual information (an extended text label), experiential interactives (touch and feel), flipbooks (hard copy or electronic multimedia stations providing additional contextual information), and finally through an interactive website (see www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/australian_journeys) that captures the extensive background research underpinning each story or exhibit.

64 This is already happening on commercial websites such as taste.com.au.

65 The choice of the pound cake invokes the importance of cake and dessert recipes in Australian cookbook publishing, but is also a reminder of the popular support for Belgium during the First World War. This is demonstrated by other Australian cookbooks, such as the Presbyterian Cookery Book and the Australian Missionary Cookery Book, published in 1915, which diverted funds to the 'Belgian need'. See Sarah Jane Shephard Black, '"Tried and tested": Community cookbooks in Australia, 1890–1980', PhD thesis, University of Adelaide, 2010.