In the 1950s, three examples of mural art depicting extinct creatures, The Age of Reptiles, The Age of Mammals and the 'King of the Sea' or Kronosaurus queenslandicus, were painted as decorative and instructive images on the walls of the new Geology Museum at the University of Queensland. Despite heritage-listing, these murals have not fared well in terms of their visibility, something this study seeks to redress by setting them in the local historic and artistic context as well as in relation to the development of palaeoart worldwide.

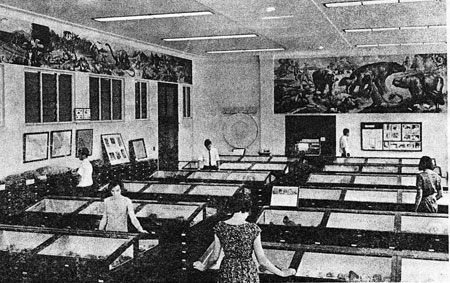

In the 1950s, during the construction and decoration of the University of Queensland at its new St Lucia site in suburban Brisbane, three murals were painted on the walls of the Geology Museum in what is now the Richards Building. The subject of the first picture was The Age of Reptiles while the second depicted The Age of Mammals (or, more specifically, local megafauna). The third celebrated the giant marine reptile Kronosaurus queenslandicus, described in a 1936 newspaper article as the 'King of the Sea' that 'swam in the seas of Central Australia' 110–100 million years ago.[1] The museum is now located elsewhere; and although the heritage-listed murals survive, they are largely ignored since they are situated in a restricted access laboratory.

The 1936 article goes on to argue for the value of studying and restoring fossils:

The discovery of these fossil skeletons of monsters of the past presents to scientists definite evidences of the processes of evolution.As the telescope enables the astronomer to look far into space and thrill us with the magnitude of things once unknown, so the study of fossils enables the palaeontologist to look far back into time, and reconstruct to some degree the wonderful life of the remote part of our earth millions of years before the coming of man.[2]

But if this study does allow the palaeontologist 'to look far back into time, and reconstruct to some degree' past life, the issue of degree is a significant one. Pictures that seek to re-create and vivify extinct creatures ('palaeoimages' in recent terminology[3]) raise interesting issues about what we mean by realism as well as the relationship between art and science. They are dependent on current scientific notions and can easily seem out-of-date as ideas about these creatures change. Do they thereby become worthless? Or does their status as works of art or as indicators of particular historical ideas and values make them significant? While they aim to convince with their realism, such representations are also highly conventional, characterised as they are by what Stephen Jay Gould describes as 'unnatural crowding and pervasive predation'.[4]

In other words, palaeoart has a history. One of my aims in this study is to situate the University of Queensland murals within this wider history by describing their precursors, possible influences, and relationship to other noteworthy examples from the mid-twentieth century. This will enable an evaluation of their claims to heritage significance. Other goals include enhancing their visibility and reviving the intended memorial function of the Kronosaurus mural. I begin by describing the murals and the particular events that led to their presence at St Lucia, including the dramatic circumstances surrounding the painting of the 'King of the Sea'.

Designed by Jack Francis Hennessy (1887–1955) of the Sydney architectural firm of Hennessy, Hennessy & Co.,[7] the Richards Building is part of the Great Court complex (see Fig. 1), one of the first buildings to be completed in the years after the Second World War and one of the few to receive a full complement of decorative schemes, both outside and inside, something that had to be curtailed in subsequent building work as the university sought to cope with an influx of students and a cut-back in funding.[8] The Geology Department made the move to St Lucia in the summer of 1949–50 and staff members designed the frieze above the main entrance to the building.[9] Both Frederick William Whitehouse (1900–73) and Dorothy Hill (1907–97), two very successful graduates of the department who returned to teach and undertake research at the University of Queensland after obtaining postgraduate qualifications from Cambridge, were involved.[10] Whitehouse's reputation has been tarnished by the circumstances surrounding his resignation from the University of Queensland in 1955 (he was being prosecuted on a morals charge). According to Hill in her 1981 history of the department, he was 'charismatic, vital, and a bachelor, enthusiastic about his teaching, his research, his U.Q. Dramatic Society and Rowing Club activities, and his various amusements'; his resignation was a 'grievous blow'.[11]

The low relief scene above the main entrance depicting dinosaurs and vegetation was carved in sandstone by John Theodore Muller (1872–1953). German-born and trained, Muller carried out most of the stone carving done at St Lucia between 1939 and his death in 1953. The various relief panels were designed by others, but he was responsible for the preparation of final cartoons and any adjustments that seemed necessary during the actual cutting of the stone.[12] In his 1957 guide to the university, literary scholar Frederick Walter Robinson (1888–1971) notes that the dinosaur relief:

represents a pleasant afternoon spent together by various types of dinosaurs and their contemporaries, including the first birds, against an ideal landscape of Jurassic vegetation, more than a hundred million years ago. All the animals represented were, one is assured, herbivorous, not carnivorous; hence the scene corresponds to a pastoral landscape of our own age!

There is also a carved trilobite on the left of the main door, Xystridura saint smithii, named after a former Geology Survey of Queensland officer, E Cecil Saint Smith, while an ammonite (Prohysteroceras richardsi) on the right celebrates Richards.[14]

by Don Cowen and Quentin Hole

the mural on the south wall comes nearer home. It is quite 'recent' in geological time, depicting animals that have lived and developed in Australia in the last million years. The skeletons on which reconstructions are based were found in the Pleistocene and Recent sediments, from, for instance, the Darling Downs.[17]

by Quentin Hole and Don Cowen

by Quentin Hole

Hole returned in 1958 to paint by himself the Kronosaurus queenslandicus mural (see Fig. 5). It was intended as a memorial to Heber Longman (1880–1954), the recently deceased former director of the Queensland Museum and the person responsible for identifying and naming Kronosaurus in 1924. The perceived need for such a memorial at this particular time is related to events taking place in the same year at another university museum: in 1958 the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology finally unveiled its reconstruction of an enormous skeleton of Kronosaurus collected on an expedition to Queensland in 1931–32. I will return to the politics of this situation later in this article, but at this stage I would like to signal the important precedent offered by American institutions, including some noteworthy university museums, with their decorative and instructive depictions of what Martin Rudwick has termed 'scenes from deep time'.[18] Before considering the murals further, the training and experience of the two local artists should be examined.

Brisbane-born Don Cowen served in the Australian Army from 1942 to 1946,[19] having completing his artistic training under local teacher Melville Haysom and also at the Central Technical College in Brisbane.[20] Quentin Hole was a few years younger, a country lad born in Charleville who also served briefly in the Australian Army (1945–46)[21] . Following this he studied art at the Central Technical College Art School under the auspices of the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Training Scheme.[22] Cowen and Hole seem to have been friends; they were members of the Younger Artists Group of the Royal Queensland Art Society and they also exhibited at Brian Johnstone's Marodian Gallery at 452 Upper Edward Street, Brisbane, during its brief life (1950–51), and at its successor, the Johnstone Gallery in the Brisbane Arcade (1952–57).[23] They participated in the first exhibition at the Marodian Gallery, described by Louise Martin-Chew as consisting of 'unabashed flower painting with popular appeal. There was little in this exhibition of many Brisbane-based artists to frighten the natives'.[24] They also exhibited together in a joint exhibition at the Marodian Gallery in April 1951. The Brisbane Courier-Mail reviewer Elizabeth Young favoured Hole over Cowen, writing that Hole was 'an artist of noteworthy promise' and suggesting that (in contrast to Cowen) he:

maintains an even standard in his work. Characterised by careful draughtsmanship with a delicate feeling for line, his watercolours have a pleasing unity, and in both watercolour and oil we are impressed by his sensitive colour.[25]

Cowen is described as 'broad and emotional in his approach', while his work 'is, on the whole and unexpectedly, most satisfying in one or two of his watercolours'.[26]

Most of the two artists' exhibited works were landscapes, with Hole painting inland scenes while Cowen favoured coastal or river subjects. Neither showed a particular interest in scenes from deep time. Nevertheless, the three murals are well designed and painted, especially the second and third. Detailed preliminary sketches survive for the first and second.[33] What precedents existed in Brisbane and elsewhere for them to draw upon? I have noted that they were advised by Geology Department staff, including Whitehouse, who was probably also a friend,[34] but they would also have needed artistic models. The prevailing style of art in Brisbane at this time was very conservative.[35] The traditional academic training available there would have been an excellent preparation for the process of carefully constructing these murals depicting imaginary historical scenes. But what images of deep time might have been influential?

The earliest examples of palaeoart date from the first part of the nineteenth century and draw on a tradition of biblical imagery and conventions established in natural history illustrations,[36] and also animal portraiture. It developed in the context of momentous discoveries in geology.[37] While the idea of representing different stages in the history of the earth was influenced by the tradition of depicting the different days of creation as recounted in the Bible, awareness of the great age of the earth was developing along with a flexible notion of the time length of each 'day'. Fossils were initially understood as the remains of antediluvian creatures destroyed as a result of the Biblical Flood, but the idea of a single catastrophic flood was also being challenged by the geological record. Increasingly systematic approaches to geological research established the importance of careful recording of stratigraphy and it became apparent that different layers were characterised by different fossil remains.

In Paris, comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769–1832) began the process of reconstructing extinct creatures from fossil remains. He also popularised the use of illustrations of these skeletal reconstructions. Eventually 'they became as a matter of routine the first stage in the reconstruction of complete prehistoric scenes'.[38] However, the inclusion of whole scenes from deep time in scientific works took some time to be accepted. The Geological Society in Britain frowned on speculative theories, so men of science who were anxious to preserve their professional reputations tended to avoid publishing anything that might be construed as speculative. For this reason Cuvier never published drawings where he had added a body outline and musculature to his reconstructed skeletons.[39] In other words, he eschewed publication of restorations of extinct creatures, drawings that show their 'alleged appearance during life'.[40]

hand-coloured lithograph by George Sharf (1788–1860), after an original watercolour by Henry Thomas de la Beche (1796–1855)

Another view of the prehistoric past was offered by artist John Martin (1789–1854).[42] Martin had achieved renown with his apocalyptic images of death and disaster including representations of the Biblical flood.[43] His mezzotint, The Country of the Iguanodon, used by Gideon Mantell as the frontispiece for his Wonders of Geology (1838), introduced an unfamiliar atmospheric effect in prehistoric scenes with his prehistoric creatures depicted as terrifying monsters.[44] Another important development in the history of ideas about the prehistoric past was the creation of three-dimensional models of prehistoric creatures. In Britain Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807–89) produced examples of dinosaurs under the advice of English comparative anatomist Richard Owen (1804–92), who invented the name 'dinosaur'.[45] In 1854 these still-surviving models were displayed in the grounds of the relocated Crystal Palace at Sydenham.[46] According to Stephen J Gould, they were responsible for the first instance of dinosaur-mania.[47]

In the case of painted or engraved images, the main conventions of the genre were established in the 1860s, with the illustrations included in The Earth before the Deluge (1863) by Guillaume Louis Figuier (1819–94) being especially influential. The artist Edouard Riou (1833–1900) represented different stages of evolution in a series of scenes in which a wide variety of creatures are gathered together. Such images were usually designed for popular appeal, frequently being used in literature aimed at children.[48]

Illustration 25 from AS Romer, Man and the Vertebrates, Penguin, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 1954 (1933), vol. 1

Knight went on to paint scenes from deep time for many museums, including the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. The images for the Field received wide circulation when they were used as illustrations in Alfred Sherwood Romer's Man and the Vertebrates (first published in 1933).[53] Knight specialised in animal imagery, arguing in an article on the topic that 'Animal painting is a difficult art, more particularly if one is serious minded and not just dabbling with no real aspirations in any particular line'.[54] In summary, he writes:

Far more than in figure painting, therefore, it is necessary to know something of the anatomy of the creature you desire to portray, and you simply must acquaint yourself with the important points in its general physical make-up. But one must also have an insight into the psychology behind the animal's actions because this psychology is the controlling element in its emotional responses.[55]

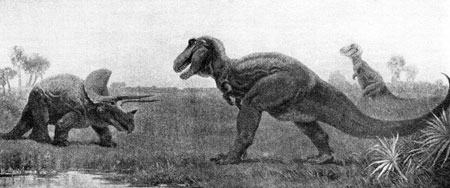

This emotional intensity is evident in his palaeoimages, some of which, such as his encounter scene between Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops, were very influential (see Fig. 7). Indeed, this image is reproduced in the Dinosaur or 'Playasaurus' Garden at the Queensland Museum in Brisbane, re-opened in 2009 after refurbishment (see Fig. 8).

from 'The world we live in', Life, 7 September 1953

by Don Cowen and Quentin Hole

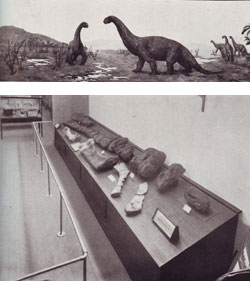

Plate 29 from Heber A Longman, 'Palæontological Notes: Rhoetosaurus brownei', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 1929, facing p. 250

Closer to hand, the Queensland Museum and Heber Longman, its director between 1918 and 1945, provided some visual models.[66] Longman, a former journalist and newspaper owner as well as an enthusiastic amateur naturalist, developed expertise in palaeontology.[67] He was a keen promoter of the museum and its contents in local newspapers and he encouraged the use of images and illustration as an aid to display. In the 1920s he set up a display of the local herbivorous dinosaur, Rhoetsaurus brownei, which included a painting of the creature in its environment done by Douglas S Annand (1903–76), another local artist and graphic designer trained at the Central Technical College (Fig. 11).[68] Longman also established links with the University of Queensland, becoming a part-time lecturer in palaeontology and collaborating with Whitehouse,[69] so he is another possible source of advice for the artists.

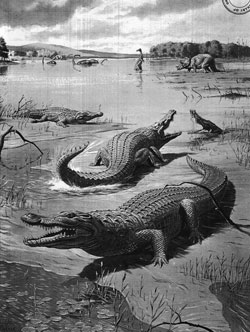

Fig. 12.

The Scourge of the Dinosaurs: A Giant Crocodile of 80,000,000 Years Ago

by Neave Parker

from

Illustrated London News, 22 December 1951, p. 1043

In a 1921 paper on Euryzygoma Longman comments:

In 1915, when describing a giant turtle from the Queensland Cretaceous formations, the writer ventured to forecast that, when our areas were better known, novelties rivalling the grotesque monsters of other lands would be exhumed In life, this mammal must have been bizarre as a monster in an artist's realm of phantasy.[75]

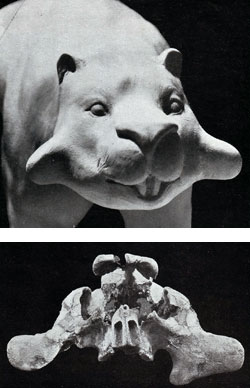

Plate 30 from Heber A Longman, Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 1934, facing p. 202

Journalist Clem Lack responded to Longman's ideas about the creature in a 1936 article on Longman and the museum, dubbing the creature 'Eury The Slobberer' and describing it as 'the weirdest fossil in the collection' and 'a bizarre marsupial type from the Cainozoic'.[76] However, although viewers may well be struck by its curious appearance, its apparently cheerful expression and the direction of its gaze make it appealing as well. It is also a convincing depiction: the naturalistic style deriving from Renaissance art with light and shade creating a three-dimensional effect on a two-dimensional surface is a rhetorical device as well as a representational one.[77]

Other adjustments in the final picture result in less 'pervasive predation' (replaced by imminent attack in the case of the thylacine and lungfish in the left foreground) and an overall slight reduction in clutter. Two reptiles, a large horned turtle (known as Meiolania oweni then, now renamed as Ninjemys oweni) and a giant carnivorous lizard, Megalania, are moved to centre stage, also an improvement. Megalania stands upright, with a bright blue tongue, while the turtle escapes the jaws of a giant crocodile in the sketch to be merely menaced by it in the final work. Again, both creatures appear to interrupt their activities in order to examine the viewer, as do the giant kangaroos in the left middle ground. Although overall the picture is static, the artists have introduced some movement by varying stances, avoiding too great a reliance on profile specimen-like poses. The sense that various attacks are about to take place adds a note of tension. The vibrant use of colour also attracts interest. This can be attributed solely to Hole and Cowen, since any possible sources such as Parker's newspaper illustrations based on his gouache and wash preparatory drawings or the Knight image included in Romer were black and white. It is a striking and unique picture and a significant achievement for the two artists as they prepared themselves to quit Brisbane for overseas.

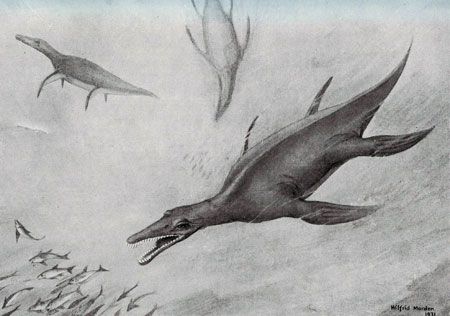

The 1958 mural depicting Kronosaurus queenslandicus is the most accomplished of the three pictures, benefiting perhaps from Hole's trip to Europe, where he viewed art in England, France and Italy.[78] The choice of viewpoint, composition, scale and handling of paint are all very effective in conveying a dramatic image of this enormous, air-breathing marine reptile with teeth 'the size of bananas'.[79]

The project was initiated by Irene Longman (1877–1964), the wife of Heber Longman, and the first woman to be elected to the Queensland parliament, where she served as Member for Bulimba from 1929 to 1932.[80] In 1957 she wrote to the University of Queensland proposing a monetary donation for a Kronosaurus mural that would be situated in the Geology Museum. She stated that the work would be 'in memory of my husband' (who had died in 1954) and that she would be 'happy to pay for the work of the artists engaged if the cost is not beyond my capacity'. Accuracy was to be an essential ingredient:

It is, I know, unnecessary to suggest to you that the artists, who are not palaeontologists, should not introduce into the sketch (for artistic or other reasons) specimens belonging to other geological periods.[81]

This would be an appropriate memorial, since the fragmentary type specimen, held in the Queensland Museum, had been identified, christened and described by Longman in 1924. The name refers to the ancient Greek Titan Kronos who devoured his children.[82] The discovery was important in establishing Longman's reputation in spite of his lack of formal training in geology or palaeontology.[83] He seems to have regarded the creature as a particular favourite, recording further fragments in 1930.[84] In one 1936 newspaper article he describes Kronosaurus as 'a pliosaur, a terrible reptilian monster, half crocodile, half fish, which basked in the Cretaceous seas of Western Queensland'.[85] In a more popular vein, Longman declared: 'It must have been more terrible a reptile than [novelist] Zane Grey's "White Death Sharks" ... Without doubt ... King of the Sea'.[86]

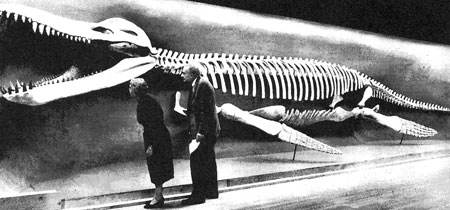

Heber Longman regretted the loss of this potential exhibit.[91] Furthermore, in the United States there was a general lack of acknowledgement of his role in identifying and naming Kronosaurus queenslandicus. Science News Letter triumphantly announced that 'THE ONLY complete 100-million-year-old fossil skeleton of what was once the largest flesh-eating reptile in the sea has been reconstructed at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge'.[92] No mention was made of Longman or of any local help in locating the specimen; instead Schevill is celebrated as the discoverer of the creature.[93]

Plans for the reconstruction were long known in Queensland and there was dissatisfaction that Longman was being neglected. Indeed, under the heading 'WAS QUEENSLAND MONSTER', the Courier-Mail in April 1956 informed the public that 'Bones of a 50ft. sea monster, being restored in the U.S., were discovered in Queensland'.[94] In the article, University of Queensland Geology Professor, WH Bryan, describes the true circumstances of the discovery and naming of the creature, noting that the Harvard University collector 'was directed to the specimen' he collected, but also acknowledging that restoration of the specimen was beyond the financial capacity of local institutions.[95] The mural was well-advanced on 6 June 1958 when the Courier-Mail gave the local public 'A look at Kronosaurus Queenslandicus' just days before the unveiling of the Harvard reconstruction (details of which are contained in the article). Under a photograph of two staff members viewing the 'spectacular' picture, the sub-heading 'Local credit for monster' makes clear that the picture was part of the campaign to restore Longman's role in the story of Kronosaurus. Indeed, the article begins by stating, 'Queensland University has sent a firm reminder to America that the man who "discovered" and named the world's biggest marine reptile was a Queenslander' (in the form of a letter from Bryan to Harvard), and it goes on to recount the history of the finding and identification of the original specimen.[96]

from Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 10 no. 2, facing p. 98

When the vice-chancellor, JD Story, wrote to Mrs Longman in June 1958 thanking her for her donation as well as for her 'keen interest and practical help', he suggested that 'the mural will be of absorbing wonderment for countless visitors'. He also stated: 'To me, personally, the linking of your husband's names with the University is a great pleasure. As colleagues, our comradeship was long and close'.[103] Today there is no notice of the memorial function of the mural. Nor is it possible to view the image in its entirety, as it is bisected by a window with part in a corridor and the rest in a private office.

The Geology Museum in the Richards Building became a student laboratory in the later 1960s in response to a great influx of students at that time. A new museum was established in another building by the early 1970s. Space pressures are a constant problem at the University of Queensland, perhaps providing the most significant reason for abandoning the original setting for the murals; but changes in scientific conceptions of dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures probably also played a role. The pictures quickly became old-fashioned exemplars of outworn theories, especially the first mural, but they could still be the starting point for discussions about changes in scientific ideas. This approach is taken by the Queensland Museum in its Playasaurus Garden, where the illustration is supported by written texts to assist understanding. More marginalisation of the University of Queensland murals occurred in January 2003 when the space they occupied was turned into 'a modern fully refurbished area' for the Stable Isotope Geochemistry Laboratory. Although a 'special effort was made during refurbishment of the lab space to preserve the heritage-listed murals',[104] they remain hard to see.

The murals are significant heritage items, unique in Australia and valuable in the context of worldwide palaeoart. They deserve to be more easily viewed and better known.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

1 Ray Roberts, 'It swam in the sea of Central Australia!', Queenslander, 28 May 1936, p. 9. Roberts is quoting Heber Longman, director of the Queensland Museum at that time.

2 ibid.

3 Allen A Debus & Diane E Debus, Paleoimagery: The Evolution of Dinosaurs in Art, McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2002, pp. 7–8.

4 Stephen Jay Gould, 'Preface: Reconstructing (and deconstructing) the past', in Stephen Jay Gould (ed.), The Book of Life, Ebury Hutchinson, London, 1993, 6–21, p. 9.

5 Dorothy Hill, 'The first fifty years of the Department of Geology of the University of Queensland', Papers of the Geology Department of the University of Queensland, vol. 10, no. 1, 1981, 1–68 (p. 1); see pp. 6, 8 for more information about Richards and his personality. See also Barry Woodworth, 'Geological research in Queensland', Semper Floreat, 4 August 1954, p. 3.

6 Hill, 'First fifty years', p. 31.

7 See 'University of Queensland, Great Court Complex', Cultural Heritage Register, Place ID 601025.

8 See Malcolm I Thomis, A Place of Light & Learning: The University of Queensland's First Seventy-Five Years, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1985, especially pp. 212–13.

9 Hill, 'First fifty years', pp. 35–6.

10 On Whitehouse, see Richard E Chapman, 'Whitehouse, Frederick William (1900–1973)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 16, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 2002, p. 538. Whitehouse began lecturing on palaeontology and stratigraphy in 1926, replacing WH Bryan who lectured on these topics between 1920 and 1926: Hill, 'First fifty years', p. 17. On Hill, see KSW Campbell & JS Jell, 'Dorothy Hill 1907–1997', Historical Records of Australian Science, vol. 12, no. 2, 1998, www.science.org.au/academy/memoirs/hill.htm.

11 Hill, 'First fifty years', pp. 17, 41 ('grievous blow').

12 FW Robinson, 'Obituary: John Muller', University of Queensland Gazette, June 1953, p. 10. See also HJ Summers, 'A German craftsman leaves his mark on St Lucia University', Courier-Mail, 17 November 1951, p. 2.

13 FW Robinson, The University of Queensland, St Lucia Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1957, p. 25; on Robinson, teacher of English and German at the University of Queensland, see Nancy Bonnin, 'Robinson, Frederick Walter (1888–1971)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 11, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1988, pp. 424–5.

14 Robinson, University of Queensland, p. 25.

15 Hill, 'First fifty years', p. 36. Note that the sandstone dinosaur frieze was used to adorn the cover of the Geology Department Papers.

16 Robinson, University of Queensland, p. 27.

17 ibid.

18 Martin JS Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1992.

19 Information from WW2 Nominal Roll, www.ww2roll.gov.au/.

20 Exhibition of Queensland Art Catalogue: Queensland National Art Gallery, Brisbane 10th September to 7th October 1951, Commonwealth Jubilee Celebrations [1951] State Arts Sub-Committee, Brisbane, 1951, p. 11.

21 Information from WW2 Nominal Roll.

22 Exhibition of Queensland Art Catalogue, p. 16.

23 For information on the Marodian and Johnstone galleries, see the Johnstone Gallery Archive, State Library of Queensland; Louise Martin-Chew, '"Like Topsy": The Johnstone Gallery 1950–1972', Master of Creative Arts thesis, James Cook University, 2001.

24 Martin-Chew, '"Like Topsy"', p. 28 (Martin-Chew lists Don Gowen amongst the artists, commenting in brackets that this 'maybe Cowan', but it must be a misprint for 'Cowen').

25 Elizabeth Young, 'Two-man effort', Courier-Mail, 5 April 1951, p. 2.

26 ibid.

27 WL, 'Christmas art show', Courier-Mail, 11 December 1951, p. 2.

28 Letter dated 8 October 1951 from JL Treloar, director of the Australian War Memorial to Miss Daphne Mayo, Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library, Papers of Daphne Mayo, UGFL 119. Thanks to Cassie Doyle for this reference.

29 See Acquisitions 1951–1953, Queensland National Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1953, p. 4, no. 13: Daisy and Violet, Oil by Quentin Hole (Purchased by the trustees). Glenn Cooke's 'Notes' in the Queensland Art Gallery file on this artist record that Hole was included 'in the first exhibition of Queensland Artists of Fame and Promise in 1952'.

30 Cowen settled in Tucson, Arizona, and continued to produce artworks there, including a mural illustrating the history of science for the University of Arizona Optical Sciences centre: see www.arizona.edu/tours/artworks/artworks3.php.

32 See Stephanie Owen Reeder, 'Quentin Hole (1923–99): Master of design and humour', Lou Rees Archives Notes, Books and Authors, no. 22, 2000, pp. 4–6; Marcie Muir, Australian Children's Book Illustrators, Sun Books, South Melbourne, 1977, p. 15; Marcie Muir, A History of Australian Childrens Book Illustration, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1982, p. 137; Robert Holden, Koalas, Kangaroos and Kookaburras: 200 Australian Children's Books and Illustrations 1857–1988, Bloxham and Chambers, Sydney, 1988, p. 48; and Walter McVitty, Authors & Illustrators of Australian Children's Books, Hodder and Stoughton, Sydney, 1989, p. 96.

33 Fryer Library, University of Queensland Library, UQFL 459.

34 Personal communication via email from Dr Andrew Simpson, 10 February 2009.

35 See Glenn R Cooke, A Time Remembered: Art in Brisbane 1950 to 1975, Queensland Art Gallery, South Brisbane, 1995, p. 34.

36 I am indebted to the work of Martin Rudwick in his Scenes from Deep Time in this section.

37 ibid., pp. 20; 27–30.

38 ibid., p. 32.

39 ibid., pp. 35–6; see also pp. 56–8; for more on Cuvier, see Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, pp. 20–3.

40 See WE Swinton, Dinosaurs, Trustees of British Museum (Natural History), London, second edition, 1964 [1st edition 1962], pp. 38–9.

41 Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time, pp. 43–8. On the aquarium craze and the development of the underwater viewpoint, see Stephen Jay Gould, Leonardo's Mountain of Clams and the Diet of Worms, Vintage, London, 1999, pp. 57–73 ('Seeing eye to eye, through a glass clearly').

42 See Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time, pp. 21–4.

43 See William Feaver, The Art of John Martin, Clarendon, Oxford, 1975.

44 Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time, pp. 78–82; see also Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, pp. 24–31.

45 For a useful summary of Owen's background and approach, see Jacob W Gruber, 'Owen, Sir Richard (1804–1892)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004, www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21026.

46 Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, p. 42; see pp. 42–7 ('Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins — a modern Pygmalion'); also Gould, 'Reconstructing (and deconstructing) the past', pp. 6–7.

47 Stephen Jay Gould, Bully for Brontosaurus: Further Reflections in Natural History, Penguin, London, 1991, p. 97.

48 Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time, pp. 238–53; Gould, 'Reconstructing (and deconstructing) the past', pp. 16–17.

49 Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, pp. 83–96.

50 William H Ballou, 'Strange creatures of the past: Gigantic saurians of the Reptilian Age', Century Magazine, vol. 55, no. 1, November 1897, 15–23. Many of Knight's images can be seen online at www.charlesrknight.com.

51 Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, p. 8.

52 'Personalities in paleontology: Charles Knight', available online from the American Museum of Natural History: www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent/fossilhalls/personalities/bios/knight.php; see also Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, pp. 48–51; Gould, 'Reconstructing (and deconstructing) the past', pp. 17–19.

53 Alfred Sherwood Romer, Man and the Vertebrates, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1933.

54 Charles R. Knight, 'What are they thinking?', Natural History, February 1938, www.naturalhistorymag.com/editors_pick/1938_02_pick.html.

55 ibid.

56 WJT Mitchell, The Last Dinosaur Book: The Life and Times of a Cultural Icon, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1998, p. 101.

57 Rudolph Zallinger, 'The making of The Age of Reptiles mural', www.peabody.yale.edu/explore/makingmural.html; see also Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, pp. 108–10.

58 Vincent Scully, 'THE AGE OF REPTILES as a work of art', in Vincent Scully et al., The Great Dinosaur Mural at Yale: The Age of Reptiles, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1990, pp. 14–15.

59 ibid., pp. 6–17.

60 ibid., pp. 6, 16.

62 ibid., p. 15.

63 For further discussion, see Andrew Darley, 'Simulating natural history: Walking with Dinosaurs as hyper-real edutainment', Science as Culture, vol. 12, no. 2, 2003, 227–56; Karen D Scott & Anne M White, 'Unnatural history? Deconstructing the Walking with Dinosaurs phenomenon', Media Culture Society, vol. 25, no. 3, 2003, 315–32.

64 See Gould, Bully for Brontosaurus, pp. 94–103 ('The dinosaur rip-off').

65 This idea began in the late nineteenth century with OC Marsh's reconstruction of Brontosaurus: see Gould, Bully for Brontosaurus, pp. 88–9; Gould, 'Reconstructing (and deconstructing) the past', pp. 12–13.

66 The museum was situated in the former Exhibition Building from late 1899 until 1984: Patricia Mather, A Time for a Museum: The History of the Queensland Museum 1862–1986, Queensland Museum, Brisbane [published as vol. 24 of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum], 1986, pp. 22–33.

67 JCH Gill, 'Longman, Albert Heber (1880–1954)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 10, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1986, pp. 138–9.

68 Bettina Macauley, 'Annand, Douglas Shenton (1903–1976)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 13, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1993, p. 60; Heber A Longman, 'Palæontological notes', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 9, no. 3, 1929, pp. 247–51. See also Heber A Longman, 'The giant dinosaur: Rhoetosaurus brownei', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 9, no.1, 1927, 1–18. However, current opinion considers that the reconstruction is 'flawed in many ways': Notes on the painting, Registration Number H19511, Queensland Museum Records.

69 Hill, 'First fifty years', p. 25, notes that 'Longman gave 5 special lectures a year on vertebrate palaeontology from 1939 onwards'; see also Susan Turner, 'Vertebrate palaeontology in Queensland', Earth Sciences History, vol. 5, no. 1, 1986, 50–65; Susan Turner, 'Heber Albert Longman (1880–1954), Queensland Museum scientist: A new bibliography', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 51, no. 1, 2005, 237–57 (p. 242).

70 Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, 111–14.

71 See Illustrated London News, 22 December 1951, p. 1043. This is the only such scene I found looking through the extensive, albeit slightly incomplete, holdings of this newspaper for the period 1951–52 in the State Library of Queensland. Some dioramas of 'Extinct prehistoric sea creatures' 'Re-created for Chicago Museum' were illustrated on p. 707 of the issue dated 3 November 1951, while an assemblage of Australian marsupials (not an integrated scene) drawn and painted by Parker appeared in a double-page spread in the issue for 29 March 1952, pp. 548–9.

72 AS Romer, Man and the Vertebrates, Penguin, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 1954 (1933), vol. 1, Illustration 50.

73 Turner, 'Heber Albert Longman (1880–1954)', p. 238. For a history of discovery and identification of Darling Downs fossil remains, see Susan Turner, 'Vertebrate palaeontology in Queensland' (pp. 51–4).

74 Heber A Longman, 'Restoration of Euryzygoma dunense', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 10, no. 4, 1934, 201–02 (p. 201).

75 Heber A Longman, 'A new genus of fossil marsupials', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 7, no. 2, 1921, 65–79 (p. 65). It might be argued that Longman is ignoring here the long history of discovery of prehistoric creatures in Australia, but his emphasis probably concerns the very unusual appearance of this animal. For the historical background, see Patricia Vickers-Rich & Neil W Archbold, 'Squatters, priests and professors: A brief history of vertebrate palaeontology in Terra Australis', in P Vickers-Rich, JM Monaghan, RF Baird & TH Rich, Vertebrate Palaeontology of Australasia, Pioneer Design Studio, Lilydale, Victoria, in association with Monash University Publications, 1991, pp. 1–43.

76 Clem Lack, 'Musing round the museum: Mr. Longman is proud of the skeletons in his cupboard', Courier-Mail, 10 October 1936, p. 23.

77 See Martin Kemp, 'Temples of the body and temples of the cosmos: Vision and visualization in the Vesalian and Copernican revolutions', in Brian S Baigrie (ed.), Picturing Knowledge: Historical and Philosophical Problems Concerning the Use of Art in Science, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1996, pp. 40–85; and David Topper, 'Towards an epistemology of scientific illustration', in ibid., pp. 215–49.

78 McVitty, Authors & Illustrators, p. 96.

79 'Kronosaurus queenslandicus', www.qm.qld.gov.au/features/dinosaurs/queensland/kronosaurus.asp.

80 Mary O'Keeffe, 'Longman, Irene Maud (1877–1964)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 10, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1986, pp. 139–40.

81 Information from the University of Queensland Archives: UQA S15 Minutes of the Buildings and Grounds Committee, 23 September 1957.

82 Heber A Longman, 'A new gigantic marine reptile from the Queensland Cretaceous: Kronosaurus queenslandicus new genus and species', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 8, no. 1, 1924, 26–8.

83 Turner, 'Heber Albert Longman (1880–1954)', p. 241.

84 Heber A Longman, 'Kronosaurus queenslandicus: A gigantic Cretaceous pliosaur', Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, vol. 10, no. 1, 1930, 1–7.

85 Lack, 'Musing round the museum', p. 23.

86 Roberts, 'It swam in the sea of Central Australia!', p. 9.

87 Mather, Time for a Museum, pp. 58, 140.

88 See 'Australian fossils for the Harvard Museum', Science, vol. 77, no. 1992, 3 March 1933, 232–3 (p. 233).

89 Alfred Sherwood Romer & Arnold D Lewis, 'A mounted skeleton of the giant plesiosaur Kronosaurus', Breviora, no. 112, October 1959, 1–15 (p. 2). Arnold Lewis directed the process of reconstruction, with work being carried out by James A Jensen and David Fuller, while Romer was the scientific advisor.

90 For further discussion, see PV Rich & GF van Tets (eds), Kadimakara: Extinct Vertebrates of Australia, Pioneer Design Studio, Lilydale, Victoria, 1985, pp. 147–51; Allen A Debus, 'Kronosaurus — an imaginary sea monster that got away', in Debus & Debus, Paleoimagery, pp. 13–19; and John A Long, Dinosaurs of Australia and New Zealand, UNSW Press, Sydney, 1998, pp. 138–42. Recent advice from Dr Alex Cook of the Queensland Museum states that there is only one species of Kronosaurus: personal communication via email, 11 March 2009.

92 'Ancient fossil exhibited', Science News Letter, 14 June 1958, p. 373. See also 'Ancient monarch of the seas', Natural History Magazine, June 1959, 22–23, www.oceansofkansas.com/kronosar.html.

93 'Ancient fossil exhibited', p. 373. For the response in 1933, see 'Australian fossils for the Harvard Museum', Science, vol. 77, no. 1992, 3 March 1933, pp. 232–3.

94 'Was Queensland monster', Courier-Mail, 27 April 1956, p. 5.

95 ibid.

96 'A look at Kronosaurus Queenslandicus', Courier-Mail, 6 June 1958, p. 3. When Romer and Lewis published a scientific paper on the reconstructed skeleton in 1959 they did include details of Longman's role and that of the local resident ('A mounted skeleton of the giant Plesiosaur Kronosaurus', pp. 1–15) as did an article published in 1959 in the Australian Museum Magazine (although the role of the local landowner is not acknowledged): HO Fletcher, 'A giant marine reptile from the Cretaceous rocks of Queensland', Australian Museum Magazine, vol. 13, no. 2, 1959, 47–9.

97 Plate 15: Ideal Scene of the Lias with Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus.

98 Reproduced as Illustration 41 in Romer, Man and the Vertebrates, vol. 1, 1954.

99 See The Reptiles Return to the Sea, in 'The world we live in: Part V: Two billion years of evolution', Life, 7 September 1953.

100 Neave Parker, Macroplata, a Plesiosaur (postcard), British Museum of Natural History, London, 1950s.

101 Entry on 'Queensland Kronosaur' available online from the Australian Museum: www.lostkingdoms.com/facts/factsheet6.htm; see also www.qm.qld.gov.au/features/dinosaurs/queensland/kronosaurus.asp. For a recent scientific discussion of Kronosaurus, see Benjamin P Kear, 'Cretaceous marine reptiles of Australia: A review of taxonomy and distribution', Cretaceous Research, vol. 24, 2003, 277–303 (pp. 291–3).

102 Gould, 'Reconstructing (and deconstructing) the past', pp. 10–11.

103 Letter dated 18 June 1958 from JD Story to Mrs I Longman, The University of Queensland Archives: UQA S130 – File – Murals – St. Lucia Buildings.

104 'SIGL NEWS', www.uq.edu.au/geoche.