Australia's newest national garden opened at Cranbourne, in the south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne, in May 2006. The Australian Garden, part of the Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne, is billed as a 'journey into the Australian landscape'. It is the centrepiece of the 363-hectare site, some ten times the size of its very much older partner, the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, established in 1846, which features 'picturesque' landscapes designed by William Guilfoyle in the 1870s. Stage 1 of the Australian Garden covers 11 hectares, contains 100,000 plants of over 1000 species, and features 1000 mature trees — the oldest of which, the grass-trees Xanthorrhoea, have been growing for nearly half a millennium. Work on Stage 2, a further 10 hectares, will commence in 2007, and is expected to be complete by 2010.

photograph by Janusz Molinski

Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne

The journey begins in the 'heart of Australia' in the Red Sand Garden, a massive sculpture featuring grey-blue saltbush and crescent-shaped lunettes carved out of deep red sand. It was designed by landscape architects Taylor Cullity Lethlean in association with plant designer Paul Thompson. For a good view of the whole sculpture, you need to climb the platform at the Trig Point, a short stroll from the Visitors' Centre. Otherwise, you are encouraged to explore it by walking around it (not over it), just as you are if you visit Uluru, the original 'red heart' of Australia.

A visitor walking around the edges of the Red Sand Garden, the 'red centre' of this miniature Australia, consciously or unconsciously imitates the way Australians cling to the coastal fringes of the continent itself. 'No public access', say the signs on the perimeter fence. But the local wildlife can't read. Amid Mark Stoner and Edwina Kearney's Ephemeral Lake sculpture — about 60 square metres of red sand with long curvaceous ceramic forms suggesting water — there was an unexpected enhancement. The sculpture was criss-crossed with the pawprints of an active colony of southern brown bandicoots (Isoodon obesulus nauticus), a threatened species that is prospering in the fenced, cat-free security of the Cranbourne gardens. Life mimics art as their prints take the eye to the ceramic 'water'.

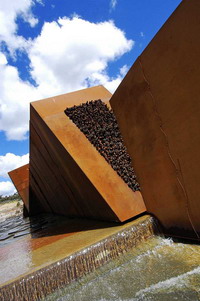

The Red Sand Garden is itself a grand-scale artwork — and its highest point is another — the Escarpment Wall, by Greg Clark, built from huge blocks of red, rusted steel. The wall abuts the full-length, shallow Rockpool Waterway, where children are encouraged to wade, but not swim, 'between the flags'.

Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne

I arrived at the garden in the early morning, and its features were picked out for me by the low rays of a faintly warm winter sun. The Desert Discovery Camp at the far extreme from the Visitors' Centre provided a good base from which to consider the garden as a whole. The mild air carried the constant ringing of bell miners (Manorina melanophrys) and the twitter of superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus), reminding me that the splendid desert landscape at my feet did not really 'belong' at Cranbourne. But the visuals were persuasive: sandy soil dotted with the silver grey foliage of Eremophila, the stately grass-trees in the middle distance, and extended pebble gardens of various shapes and sizes all around. The camp's main feature is a large sandpit, at the end of a concrete path which features the footprints of goanna, emu, kangaroo and a small human. This is a 'deep time garden' for budding palaeontologists, with 'fossils' in the walls — the oldest deepest and the newer ones nearer the top. 'Can you find the oldest "fossil" buried down deep?', it tempted me. 'Can you find the plant that dinosaurs loved to eat?'

Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne

'Water — the great storyteller of the Australian landscape', proclaimed the sign leading me out of the Desert Discovery Camp towards a dry riverbed, featuring island pockets of vegetation between wavy red gravel paths. The extensive Eucalypt Walk alongside the Dry River Bed evokes the view from the air that passengers (with a window seat) experience when they cross the continent, as well as the actual functions of the underground river itself. Nearly a third of the space is devoted to eucalypts — stringybark, bloodwood, peppermint, box and ironbark (if you walk as I did from the camp to the Visitors' Centre). Equally, the stories in the signs work the other way around, exploring the cultural as well as the natural significance of the eucalypt as the 'dominant Australian'. I began in deep time, with a quote from the historian of fire, Stephen J Pyne: 'About 34 million years ago the eucalypts appeared, quiet and unannounced'. I was also welcomed in the traditional style of the Kulin nation, with gum leaves, and turned to signs about fire and caring for country, and the warning (from anthropologist Deborah Rose's Nourishing Terrains) that 'Big fires come when that country is sick from nobody looking after it with proper burning'.

The Bloodwood Garden includes the story of Ferdinand von Mueller's sending of blue gum seeds to plant the swamps outside Rome to help eliminate malaria — for which he was awarded a papal knighthood. The Peppermint Garden evokes 'smells of home', as recalled by wartime diggers. Other signs include the stories of the gold rushes, and children lost and found in the bush.

By this stage I was struck by the fact that this is as much a 'museum' as a garden. It has been carefully constructed to be aesthetic, entertaining and cultural, as well as informative — indeed celebratory — about plants. The Melbourne Museum features a huge Forest Gallery: a Eucalyptus regnans forest encased in a building in the Exhibition Gardens on the edge of the central business district. Here was the counterpoint. In this old sandmine in the south-eastern suburbs, the Royal Botanic Gardens has developed a museum experience in a garden. The blurring of the categories is most apparent in the remaining third of the Cranbourne site, with five 'exhibition gardens' that function like galleries in a museum. The Diversity Garden samples key plants from the 85 bioregions of Australia, planted in narrow sliver-shaped gardens of pebbles of different colours and sizes. The Water Saving Garden features plants suitable for Melbourne gardens in three terraces: a 'moderate' water use terrace, a 'low' water use terrace and a 'dry' terrace, the water usage of each terrace marked by blue, yellow and red watering cans in decreasing numbers. The Future Garden is next, and provides a respite from the busy 'galleries'. The Home Garden includes a stylised house, with the front 'heritage' wall looking out onto an old-fashioned style of cottage garden, and the back 'modern' wall onto a contemporary deck with elegant plantings. To the left of the structure is the 1950s garden and to the right a 1970s 'native' garden. But, when you look more carefully, in fact, all the plants are indigenous to Australia. The message is that you can still have your 'heritage' or 'cottage' garden or any other 'look' you choose by using Australian plants, and they will require less water than introduced species.

The last 'gallery' is the Kids' Backyard, with fantastic natural wooden climbing frames and a Rockpool Pavilion with seating for adults (if they can resist climbing!) It has a view to The Waterhole and beyond, where Stage 2 will soon be under construction on Gibson Hill and Howson Hill, named for some of the gardens' important benefactors.

Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne

In some ways the new garden represents the healing of the great rift of 1873, when Mueller was ousted from his position as Director of the gardens and moved 'over the road' to continue his scientific work as Government Botanist in a herbarium removed from the public eye, while Guilfoyle was appointed to design the popular pleasure garden that made the Melbourne Botanic Garden world famous. I have a feeling that Mueller would have appreciated the celebration of the possibilities for Australian plants that Cranbourne represents, and Guilfoyle would have loved its aesthetics. Cranbourne's garden galleries open powerful conversations between ecological and horticultural sciences, and between the ideas of the Boonerwurrung people of the Kulin nation and those whose ancestors have come from other parts of the world, who together care for this place. And these galleries will only get better as they grow.

Libby Robin is a senior research fellow in the Centre for Historical Research, National Museum of Australia and a senior fellow in the Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra.